The Evolution of New Comic Book Day

Wednesdays have a different vibe than they did before. Is that a bad thing, or just different?

I love Wednesdays.

If you’ve been reading my writing or listening to my podcast for a while, this likely comes as no surprise to you. But I’m an ardent supporter of comic shops stemming from decades of visiting them on new comic book day, during which I would often share conversations — about characters, titles, creators, or really whatever comes up — with my fellow comic fans who are eager to take part in an engagement that’s equal parts routine and ceremony. The comic shop experience is inseparable from my joy of comics; you almost can’t have one without the other.

My usual visits tended to be after work, but on occasion, I would be there upon the shop opening at noon when I was particularly excited for a release. 16 You know how it is. It’s like when anything exciting comes, where you both don’t want to miss out but you also want to be part of the moment. I remember so many occasions throughout the years where the buzz was so palpable about a title that being there at open was a crucial aspect of the experience. Sharing that energy with your fellow fans became part of the comic in a way.

Since the pandemic hit, though, the work-from-home life has shifted my schedule a bit. Because of that, being at the shop at open on new comic book day has become a more regular occurrence, especially in the past couple months. And with each passing visit, I’ve increasingly noticed that something has felt different about this favorite day of mine. It just felt like Wednesdays were changing, or at least they were here in Anchorage, Alaska. What it was never quite crystallized, though.

Until Wednesday, April 28th.

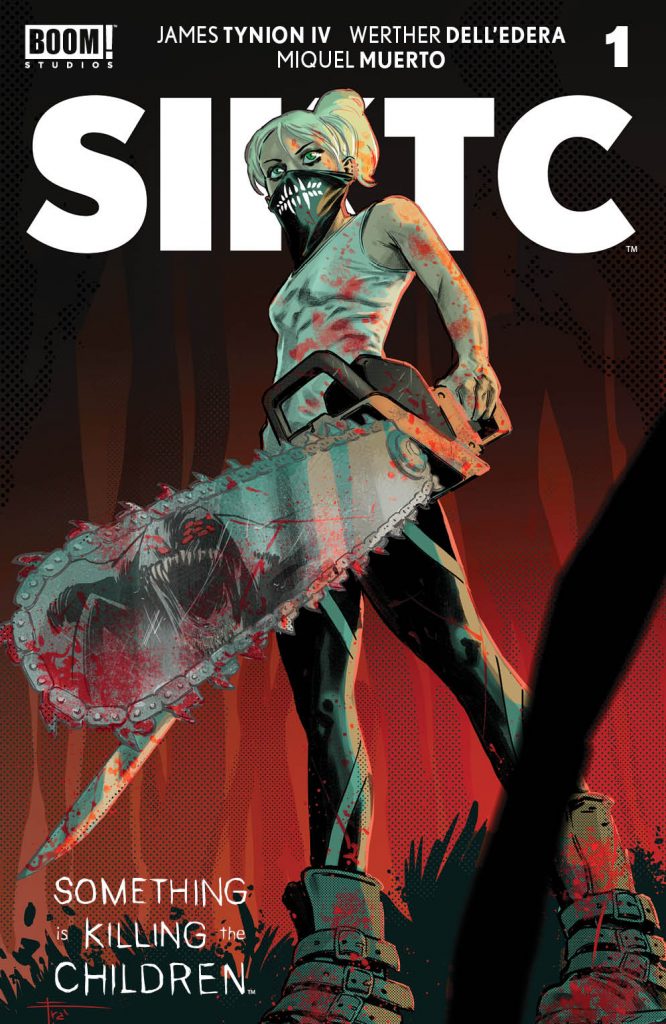

That specificity might seem totally random to you, but I know when it was because of what arrived that day. It was when BOOM! Studios released an eighth printing of Something is Killing the Children #1, an iteration of that title’s debut that was free for those who bought BRZRKR #2 that day and had proof of purchase of its first issue. I had no idea that was a thing when I walked in, but when I found, by my estimation, around two dozen people in the shop ten minutes after open, I queried the shop’s manager. He said that deluge of customers was there for those BOOM! releases, except he bristled at the idea it was out of the ordinary. This was what a normal Wednesday has always looked like, he insisted. But let me just say this: it may have looked like that, but it certainly didn’t feel like it.

As I walked around the shop, I noticed all of the customers had massive stacks of books, each of which had roughly similar compositions of titles. 17 Pockets of people formed around different releases, as they consulted their phones and snatched those their device told them what to acquire, leaving nothing more than blank backing boards behind in their wake as they wiped out the paltry inventory of small press titles in minutes. The conversations about the events within each title were gone, replaced by discussions about which variant was the right one to get or whether they found the other “keys” from that week.

And that’s when I realized what was bugging me about it: very few of these people were buying comics to actually read them, it seemed.

Now, the idea of speculators or flippers or whatever you want to call the people who buy comics to turn around and sell them immediately is not new. That premise has been around for decades, most famously in the 1990s, a stretch of time that nearly broke the comics industry. Many people compare this era to that one, with the proliferation of special covers and theoretical fast money leading to aberrant consumer behavior. But as someone who has was around for both of those periods, 18 I can tell you that the similarities are overstated. Two of the biggest differences are easy to point out, as the ‘90s were about gimmick covers, not variants — your favorite hologram or chromium covers were regular covers, not incentive variants — and the people who were looking to get rich were doing so from an inventory of often hundreds 19 on a local level and, on occasion, millions on a global one. It’s just not the same.

And these consumers know it. In fact, lower order numbers are a feature, not a bug. They’re often hunting for scarcity, not any inherently attractive characteristics to the release. Take what retailer Colin McMahon of Pittsburgh Comics tweeted me when I brought up this phenomenon on Twitter, as he said that a customer was frustrated when his shop didn’t order the second issue of a small press title because of a perceived lack of interest, with that customer saying, “But #2 is worth more than #1!” We are in an environment when later printings and later issues are worth more than #1s simply because so few shops ordered them rather than any qualitative reasons, a frankly insane place to be. 20

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

Two prominent examples from the past half decade: DC Rebirth Special and House of X #1, two titles that exist on opposite ends of the enjoyability spectrum for me as a fan.↩

How do I know that? It’s all about the ads on the back and color mixes on the covers. I’ve seen enough stacks of comics to recognize when the same ones show up over and over, especially when there are multiple of a single release. Of which there were many.↩

As a kid, albeit a hologram-thirsty one, for the first period.↩

Or more, as I’ve heard of shops from that period ordering thousands of copies of Valiant and Image titles, without even mentioning releases like polybagged editions from the story of Superman’s death.↩

Remember: a core tenet of economics is supply and demand, and when supply is low because demand is also low, that doesn’t mean scarce is good!↩

Including, and I am not kidding about this, the actual empty foil wrappers of particularly well-loved card sets, which seems bonkers. There are no cards! What is happening?! Stop spending money on this stuff!↩

When a corporation that is designed to sell as much product as humanly possible decides to bail on something that sells out instantly because people are being too crazy, you know there’s a problem.↩

Sometimes that’s a first appearance of a favorite character. Other times it’s a random entry into the Capwolf story from the 1980s. Both earn my delight in equal measures.↩

I dare you to find a single long box in a 100 mile radius with the first appearance of an even C-list Marvel character. It will be very difficult to do!↩

I caught a stray in that newsletter, as Rozanski talked about how a recent sale was all “speculative orders.” Not the order of Avengers #196, Chuck! That was me, finally getting my copy of Taskmaster’s first appearance!↩

That’s without even mentioning how horrific it must make the ordering environment for shops. How do you predict what levels second, third, fourth issues should be ordered at when number one sells out in ten minutes, but only to people looking to sell their copy?↩

Note to self: keep my pull updated and maybe start going later on Wednesdays to potentially solve my problem.↩

Until this week.↩

The first part, I mean. Not the second part.↩

FOC, the final date shops can change orders for a comic.↩

Two prominent examples from the past half decade: DC Rebirth Special and House of X #1, two titles that exist on opposite ends of the enjoyability spectrum for me as a fan.↩

How do I know that? It’s all about the ads on the back and color mixes on the covers. I’ve seen enough stacks of comics to recognize when the same ones show up over and over, especially when there are multiple of a single release. Of which there were many.↩

As a kid, albeit a hologram-thirsty one, for the first period.↩

Or more, as I’ve heard of shops from that period ordering thousands of copies of Valiant and Image titles, without even mentioning releases like polybagged editions from the story of Superman’s death.↩

Remember: a core tenet of economics is supply and demand, and when supply is low because demand is also low, that doesn’t mean scarce is good!↩