Creator-Owned and the Thin Line Between “To Be Continued” and “The End”

What does it take to survive in creator-owned comics?

This article first appeared on Multiversity Comics on June 17, 2014, but was written by me. It has been published here as well with their very kind permission.

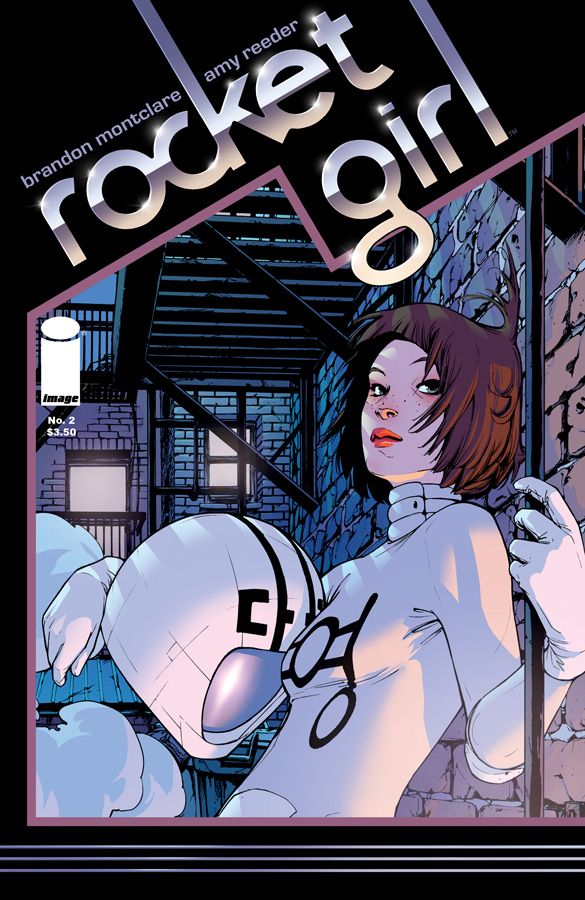

The comic industry is a very peculiar and unpredictable one, especially when you look at the world of creator-owned comics. As Brandon Montclare, writer and co-creator of “Rocket Girl” at Image Comics, recently shared in a comment at The Beat, sometimes the difference between success and failure for those titles can be the smallest of margins.

In specific, he talks about the impact monthly sales have in deciding the fate of a title after one commenter, in true internet commenter fashion, openly wonders if there is any real incentive in readers supporting independent titles on a monthly basis.

In specific, he talks about the impact monthly sales have in deciding the fate of a title after one commenter, in true internet commenter fashion, openly wonders if there is any real incentive in readers supporting independent titles on a monthly basis.

What that commenter fails to realize, and what Montclare only scrapes the edges of, is that comics exist within a delicate ecosystem. A title’s fate – especially when it is outside of Marvel or DC – can be determined before a single issue is even released, and beyond that initial launch, it takes the actions of readers, retailers and creators in various channels and forms to keep those books alive in an increasingly diverse and competitive market.

Those three groups don’t just impact the fate of a book, though. Each group impacts one another in some obvious and some not so obvious ways, and those three work together to create the special alchemy that makes the wheels of the comic book industry turn.

But why would that commenter have known that? Better yet, how could he have known that? The comic industry, like any entertainment industry, is complex in ways that the people who consume the materials could never imagine. But for comics, it could prove valuable for everyone involved to know a little bit more about one another. Today, I’m hoping to educate everyone a little bit on how things really work for the creative teams of independent titles and in the world of retail, and why it takes the efforts of everyone involved to keep even some of the best titles going.

A Primer

Before we jump into the piece, it’d be good to establish a baseline of what the “common knowledge” on the subject is to start. Carry on to the next section if you are familiar with the subject already.

Retailers order through Diamond Comic Distributors, the company who distributes the vast majority of comics to the direct market (comprised of the retail stores around the country). Diamond releases “Previews”, a catalogue of each month’s releases, with solicitations and cover/preview art for those titles, and that is a walkthrough on everything that is released. You can find this information online as well, and all of it helps guide retailers to making decisions on the quantity of each title they’d like to order.

In ye olden days, retailers would put in their orders – quite often at least partially built around the amount of customers that had X book on their pull list or had a title pre-ordered – two or three months ahead of time, and that would be that. Now, thanks to Final Order Cut-Off dates that have been added about three weeks ahead of release, retailers can adjust their orders both up and down to better fit demand, giving them increased flexibility in ensuring that they purchase the right amount of copies of any given title.

This is the system that retailers, publishers and creators exist within, and it decides whether or not you, the reader, will have a copy of a book available to purchase at your shop.

Creation Myths and Creation Realities

One thing that is important for everyone to realize is that bringing a creator-owned title to life is often a stunningly prolonged process.

“We first started thinking about “Rocket Girl” right after the publication of “Halloween Eve”…so late in 2012,” Montclare shared about when the idea for his Image project with artist Amy Reeder first came about.

Montclare and Reeder’s first issue arrived in October of 2013, which means at a minimum there were 10 months of time spent developing and crafting the title before a reader ever opened a copy.

Jim Zub, a seasoned veteran of the creator-owned game who has a new title coming in August in the delightful looking “Wayward”, knows that prolonged period all too well, and it’s not a stretch that finds creators resting on their laurels.

“With creator-owned it’s a serious uphill battle right from the start. You have to get professional material together for a pitch and then, if it’s picked up, you have the solicit cycle, actual creative production, printing, distribution, pay arriving from the distributor, and then, finally, pay arriving to the creative team (if there’s any money to be had).”

“All told you’re looking at anywhere from 6-9 months for that first paycheck. That’s half a year or more where everyone on the team has to keep the lights on and food in their belly while waiting to see the financial fruits of their labour. There’s no way that won’t have a heavy impact at every stage of production,” Zub adds.

“I know every creator says it, but a regular shipping creator-owned book is an intense creative and financial commitment.”

The time between the conception of the idea to release to payment for the very first time can lead to some very lean times for those involved, and can be very intimidating for those looking to release a creator-owned title. That’s especially when you factor in that even when a book is released, there’s still a wait before getting paid for your work.

But how long is the wait, exactly?

“The easy answer is Reed (Amy Reeder) and I get ‘paid’ from the single issues two months after the in-store date,” Montclare said.

Montclare expanded on the timeframe, and revealed how this impacts their cash flow.

“Once you get over the early hump of starting a new series, you can take advantage of cash flow. That July check (for issue #5), technically, is for February work already done. But practically speaking, it’s paying Reed and me for the work we’re doing now (which fans will see in September). Stack this all in a row like dominoes, month after month, and it’s a crude model of cash flow,” Montclare says.

“The continuing support of single issues shipping periodically and creating a pay stream is the backbone of supporting “Rocket Girl.””

That’s the meat of what that commenter – and many readers, retailers, pundits and aspiring creators beyond him – didn’t realize. Monthly comic sales for creator-owned projects are what form the living wage writers and artists need to release their books on the regular without having to take other jobs (hopefully).

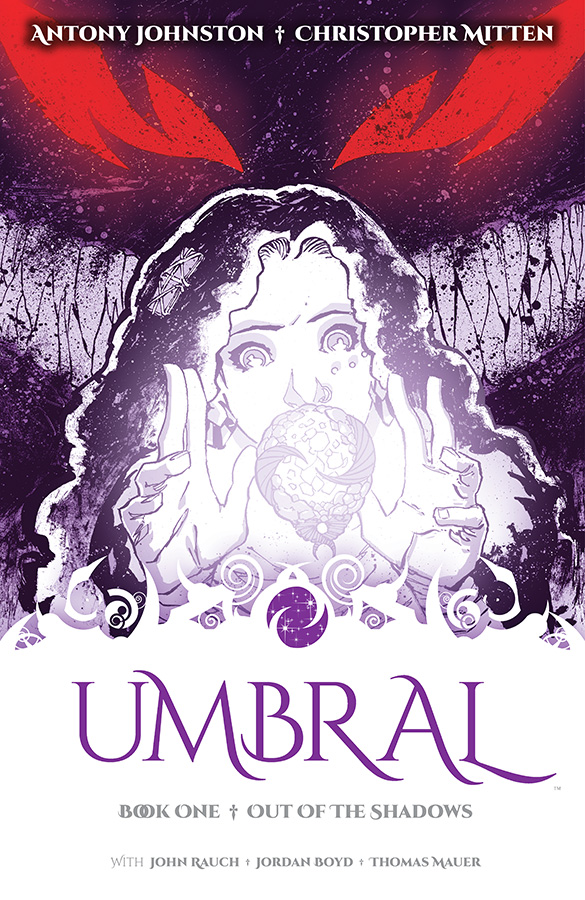

But it goes beyond just monthly sales, as Antony Johnston, writer of “The Fuse” and “Umbral” at Image shared.

But it goes beyond just monthly sales, as Antony Johnston, writer of “The Fuse” and “Umbral” at Image shared.

“Monthly issue sales are cashflow, and from that standpoint they’re very important to a book’s health.”

“That said, I think it’s folly to launch any book these days without being aware of the huge number of ‘tradewaiters’ in the comics audience, and the potential for that audience to far outstrip your monthly readers.”

Johnston shares that a big part of his audience are those very people, and that in today’s industry, trade sales are equally important to achieving success. According to Johnston, “income from good trade sales can actually sustain a book that’s not doing so well monthly.”

A good example of this, Johnston points out, is Nick Spencer and Joe Eisma’s “Morning Glories.” This dense, deep read is often compared to Lost for its ability to require rather deep reading (case in point: we have an entire column dedicated to studying it), so it likely has a readership that really sees the benefit of the easy rereadability collections offer.

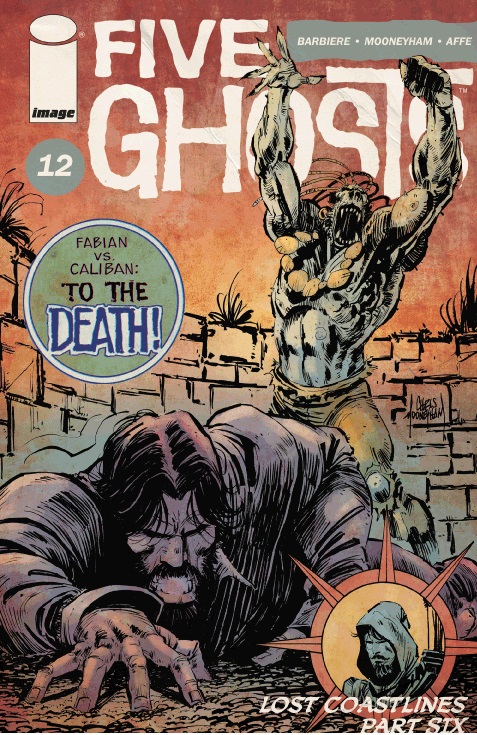

This probably plays a huge part in it staying relatively low in monthly sales, but consistently high in collection sales. Of course, it all depends on perspective, as Frank Barbiere of “Five Ghosts” doesn’t look at trades as any kind of savior.

“Trades have been wonderful and certainly pick up a lot of slack for issues, but even still those payments don’t come in regularly and can hardly be used to ‘live off of.’”

There’s certainly no single answer for how to best succeed financially in creator-owned comics, but trades and a newer part of the product mix – digital comics – are certainly increasingly important. The payments for those along with any reorders of individual issues come in lump sum checks twice a year on these books.

Barbiere looks to digital as a growing channel, but not something that makes a huge difference yet.

“Digital is still evolving. We really don’t make much from it, and while it’s great to have, it’s not as vital to our book as it is to some others.”

Zub shared that both digital and trade sales are what his book “Skullkickers” hangs its hat on at this point, but because of that twice yearly payment, it can lead to some times where money is pretty tight.

“In the case of ‘Skullkickers’ we’ve been able to keep the series rolling thanks to strong digital and trade sales, but it does mean I have to pinch every penny on it and float the expenses for months before the money is anywhere close to evening out.”

For some creators I’ve spoken to in the past – like Eisma and “Chew” artist Rob Guillory – digital is an enormous part of the mix as well, and it seems that an element like that and trade sales are a far more important part the further into your run you get, but getting there is often the tricky part. That’s why monthly sales are so important for both the long and short term, Montclare says.

“Single issues are where you usually make the most money as well as where you usually first make it. It’s the most important channel. A creator-owned publishing strategy should recognize it.”

Image’s role in all of this is a fascinating one that Montclare spoke to as well. Given that it is “creator-owned,” one might wonder how and when Image themselves get paid for the release of the books, and Montclare applauded them for how that process works.

“There are a ton of nuances, but one important note is Image’s role in cash flow. Diamond has to get paid to print Previews and collect pre-orders. The printer needs to get paid. Image staff who do things like advance publicity and pre-press and everything else needs to be paid.”

“Image fronts all of these costs, and doesn’t collect any return on a single issue until almost the exact same time the creators do.”

In an industry rife with controversy about treatment of creators, that type of business model is a refreshing and heartening fact to behold. It’s worth noting that Image isn’t the only company that does this in regards to the creator-owned model, but it is good to hear of specific examples.

Artistic collaborators are also hugely important to factor in, as writers like the ones I spoke to for this piece often are writing multiple titles to supplement their income, while artists simply do not have the time to do that, which means that creator-owned projects can be killers on a professional artist’s way of life.

Zub for one does what he can for his partners on projects. “I pay the “Skullkickers” art team a page rate (and wish I could pay them what they’re worth). That’s been the deal since the start.”

Barbiere is very passionate on the subject, and shared that he tries to be as fair as he can to the artists he works with.

“For any proposal or directly for hire work I will do my damnedest to pay out at a good rate…you can’t expect people to work for free.”

Because of the nature of creator-owned, which Barbiere compares to gambling, sometimes it’s hard to settle on a hard number for what to pay your art team, but he emphasizes that it is paramount to a creator-owned project that no matter how much your book sells, the artists involved should take priority in payback on projects.

“As a writer on a book, unless you are in fact the one driving these sales (and even then), YOU DO NOT GET PAID UNTIL YOU PAY YOUR ART STAFF. PERIOD.” Barbiere said, with emphasis coming from him.

Across the board, the people I spoke to stressed that, as the sacrifice artists often have to make in bringing a book to life would make it impossible for them to earn enough money outside of a project to make a living.

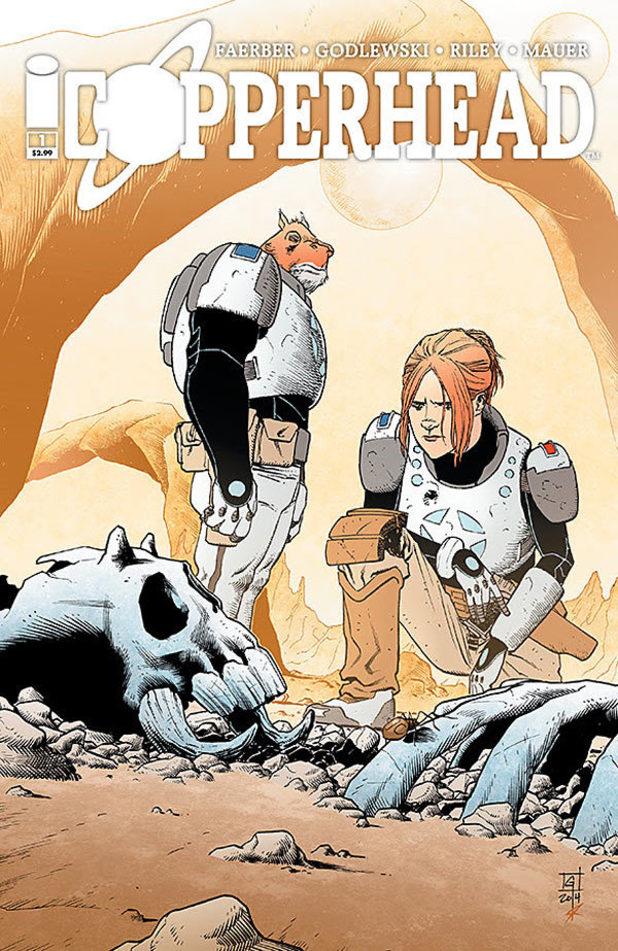

All of this made me wonder, as it might make you wonder as you read it, whether there is a clear plan for what sales a book needs at a certain point for it to continue to be viable financially. Jay Faerber, writer of the upcoming “Copperhead” at Image, shares for him that there is a plan on his projects.

“We all agree to do X number of issues, regardless of how well the book does. If we can’t sustain it past that number, we wrap it up and move on. But we’ll do that number, regardless.”

“You want to give the book time to find its audience.”

“You want to give the book time to find its audience.”

Zub tries to dodge that approach, but said it’s something that is hard to avoid.

“I’m a storyteller first and foremost so I try not to make production into a math formula, but you can’t help but feel the hard reality if those numbers end up working against you, sure.”

“The day we announced Wayward publicly I could barely sleep as those numbers kept crashing into my brain.”

Montclare said that their viability is entirely dependent on Reeder’s ability to make enough money on the project, and their make-or-break number (my words, not theirs) is 67% of her rate when she was a DC exclusive artist, something they’ve been able to equal or surpass so far in the venture. The reasoning behind her being the impetus for their success is tied to the simple, aforementioned fact of while he can take other projects during “Rocket Girl”, Reeder’s schedule prohibits her from being able to.

What Creators Can Do To Make It All Work

While there is no one size fits all answer for making a creator-owned project work, all of the creators I spoke to have learned a trick or two in their experience that have helped them find and maintain success on their projects. The first rule, above all, is you can’t just expect success to come your way.

“Up until now, I used to be a ‘build it and they will come’ kind of guy. I wanted to focus on putting out the best book I could, with the hopes that it would find its audience. I’d do the usual round of interviews on the various comic book websites, but that’s about it,” Faerber said, before adding, “but with “Copperhead,” and the other new series I’ve got waiting in the wings, I’m making a much more concerted effort to reach out to retailers. If I could change one thing about my previous creator-owned work, it would be that. I should’ve done a lot more retailer outreach.”

“But I’ve come around just how unavoidably important it is to go the extra mile when trying to launch a new creator-owned book.”

That extra mile can be the difference between long-term success and a book ending early in its run. A huge part of that ties into maintaining good relationships with retailers around the country, because they are the people who hold the fate of most books in their hands.

“On the business side of things, retailers are the single most important people involved,” Barbiere said.

“On the business side of things, retailers are the single most important people involved,” Barbiere said.

“As many of us know, comics are mostly non-returnable so retailers take a huge risk when buying a book — they are basically ordering something that they can’t return, so their only way to make a profit is to sell it to an actual customer. I make it a priority to have really good communication and contact with the retail community — they are the ones who are on the ground floor and know the customer base better than anyone. I think as a creator, and especially a new creator, you need to put in the time and get to know these fine folks.”

Zub agreed with that sentiment, emphasizing that to see results, you have to put out effort.

“If I’m not dedicated and enthusiastic about it I don’t see why retailers, the frontline people putting up money for non-returnable product on their shelves, should be.”

Montclare shared that when it came to “Rocket Girl”, they did everything they could with retailers to help spread the gospel of their book.

“We’ve reached out directly to remind them of order cutoff dates, sent signed posters for their pull list customers who get “Rocket Girl,” and try to let them know we’d love to listen and help them sell our book.”

Those types of methods aren’t even above and beyond anymore. They’re practically required to make a dent in an increasingly competitive marketplace. Johnston emphasized some of the difficulties in retailer outreach though, specifically in how narrow the market can be for independent titles.

“In the US/UK direct market, 75% of all indie books are sold by around 300 stores. Hell, the top 100 of those stores make up 50% of all sales.”

This subject is something Johnston elaborated on in a post on Tumblr, and it’s something he finds concerning.

“We desperately need more of them (retailers). Having so few customers making up such a huge proportion of orders is simply not healthy for the industry. Hell, that kind of concentration isn’t healthy in any industry.”

Montclare agreed with that idea, but said that helped guide them in trying to find easier routes to expanding their readership.

“Practically speaking we try to focus on the stores where sales are strong. It’s easier to convince a store that sold out of 30 copies to up it 33% to 40. Not so easy convincing a store that sold out of 5 to up it 200% to 15 — but the net to us is the same.”

When focusing on retailers though, it’s important to not forget the readers who ultimately make up your audience.

“While it’s true that retailers are a comic creator’s ‘real’ customers, it’s also true that if enough readers make noise at their store about a particular book, it can move the needle,” Johnston shared. “After all, no amount of marketing is as effective as pure word of mouth.”

“That’s all we ask from readers, really — if you’re enjoying an indie book, tell people. Tell your friends, tell your retailer, tell your librarian, lend the trade to your friends, whatever,” Johnston continued. “It may seem like a small thing, but when hundreds or even thousands of people all do that small thing, it becomes huge.”

“And that can mean the difference between life and cancellation.”

Retail and the Key to Comic Book Success

In its original form, this article was actually going to be about the importance of readers and the usage of pull lists to the continued success of the smaller, independent titles we love. Its form clearly changed, and a big part of that was this simple fact that I never realized: pull lists and pre-ordering are no longer the important aspects to the comic book ordering process they once were for retailers.

“Customer pull list orders used to be the backbone of our ordering, but no longer,” said Patrick Brower of the Eisner Award winning Challengers Comics + Conversation in Chicago.

Steve Anderson of Third Eye Comics in Annapolis, Maryland, for one, wants to dispel the myth that pulls are an important part of the retailer process once and for all.

“I honestly think that the concept of ‘If it’s not on your pull list, you might not get it!’ is awful, and needs to go away. Comic book stores should be vibrant, magical places full of things that you may not know you’re looking for until you see and hold them in your hands.”

One smaller store – my local shop of Bosco’s Comics in Anchorage, Alaska – indicated that pulls do affect ordering still, but only for the independent titles, and this is something that is likely true for the more Mom & Pop like stores around the country.

“On most indie books, (pulls) are very important. For many (orders) are at pull numbers or slightly above. There are dozens of books every month that we only carry because someone has expressed an interest. Conversely there are dozens each month that don’t get ordered because we think we can’t sell any and nobody asks for them,” shared Eric Helmick of Bosco’s.

In reality, the way every retailer orders is different, but most orders are derived from a combination of feel and what the actual sales on a title were. While some more recent developments impact sales – some shops pay attention to social media buzz on titles, a number brought up the importance of final order cutoff dates (aka FOC dates, a window three weeks out from release that allows retailers to change orders) in impacting how they order – for most it gets down to the cold hard math of sales.

Ralph DiBernardo of Jetpack Comics in Rochester, New Hampshire, explained.

“For any consistently selling titles, our orders are based on the actual sales, not the preorder amount. We order an additional 20% of every title, beyond the actual sales average, of their first month of sales, of the previous 3 months. In some cases we order 50% over actual sales and in a few cases 75% over (“Saga,” “Batman,” “Walking Dead” sales continue to soar so we know over time these will sell).”

DiBernardo’s shop has become a very successful one, and one that has championed many indie comics and found success down that path. But for some, the ordering process Diamond Comics Distributors uses can lead them to getting burned, even with FOC dates now making things a little easier.

“My ordering is mainly based off of the most recent issue’s sales number I have, but that’s usually 2 to 3 issues back. So when people all drop the same title at once, we may get stuck with a LOT of copies of the issues in between their dropping and my adjustments catching up,” Brower said.

Diamond’s often maddening ordering system causes consternation amongst all levels of the comic industry, as it makes the promotional window such a long, overwrought span for new books – you have to promote the books at announcement, at FOC and at release – that it’s exhausting for creators, retailers and readers, and makes it difficult to separate the signal from the noise. DiBernardo shared that he for one had no issues with Diamond, and that he has seen marked improvement in their system over the past five years. Brower also added that FOC has helped make the mistakes less painful, as it gives retailers flexibility in their ordering, but until a new challenger steps up or a revolution at Diamond takes place, this is what the comic industry has to work with.

It’s something both retailers and creators are desperate to figure out, though, as retailers are the people who quite literally decide the fate of creator-owned books. As Johnston pointed out, these are the “real customers” of creator-owned books, and for a book to succeed, there must be buy-in from retailers. That’s achieved mostly in one of two ways: through name recognition or through the apparent quality or audience of the title.

“New Image series are ordered almost solely on the creators of the book. You can usually tell which ones will be winners or not. “Trees,” “Saga,” “Black Science,” “Sex Criminals,” “East of West,” etc. were no brainers,” shared Corry Brown of Zapp Comics in Wayne, New Jersey.

Anderson elaborated on the second point that “As far as ordering newer titles with unknown/unproven creators, it’s a matter of quality and if the book has an audience.”

“If the premise is exciting, the artwork is strong, and the overall presentation is there — then we will go all in. Any good retailer should be able to look at a comic book and know the potential for an audience within 30 seconds. If the potential is not there, then orders reflect that.”

Anderson pointed to Faerber’s new Image title “Copperhead” as a book that he knew would work immediately.

Anderson pointed to Faerber’s new Image title “Copperhead” as a book that he knew would work immediately.

“I can just look at the book and know it’s going to hit with fans of things like Whedon’s Firefly, fans of the Mass Effect video games, and then readers of comics like “Saga” or “Black Science”.”

“And how’d it get me? Just one striking teaser image that summed up the feel of the book perfectly.”

Anderson goes as far as to say that he emphasizes to his staff that they pay attention to comic sites so they can stay on the cutting edge of what’s hot and what’s not. Given that they receive many of the same publisher emails comic sites do, they also keep an eye on preview art and the latest news to make sure they are ordering properly for the books that catch their eyes.

DiBernardo stressed that every indie book gets a chance at Jetpack, and he elaborated on how they order on titles from creators who may be lesser known.

“With a new Image title, from an unknown team, we will check out the content and the art quality to determine how many we’ll order. This will range from 6 – 15 copies. If we have at least 2 preorders for a new title we’ll go towards the higher quantity. No preorders will mean the lower quantity. We want to give every indie title a chance to make it.”

Once the books get into their shops, everyone emphasized that if it’s a book they love, they will push the living hell out of it, which is why the quality of a project is doubly important.

“We are comic book evangelists, and it’s our job to build the audiences for these wonderful books that are coming on the market,” Anderson said. “It’s important to make sure that you have a team who can support that same vision, because no matter how big or small the store, nothing will grow readership more than having a strong rapport with your customers and knowing their tastes.”

DiBernardo echoed that, saying, “If one of our staff enjoys your book they will social media the hell out of it. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram…whatever we can do. With nearly 5,000 followers on Facebook and Twitter we let the world know if we liked a property.”

“If we think the book is a quality title it will get a better placement on new comic day and if we really like it, we’ll leave it on the new rack for multiple weeks, as well as slotting it alphabetically in the Indy section.”

Anderson shared that creators reaching out is hugely important when it comes to their ordering, and not because they are starved for attention or anything, but because sometimes it can be the difference between “getting” a project or not.

“Creators reaching out is also very important. I can’t say that every book I’ve been personally mailed about has grabbed me, but I do look at 100% of what I receive, especially if the creator makes it clear they’re reaching out on a personal level and not just a blanket mass e-mail,” Anderson said. As far as what he looks for in these emails beyond the personal touch, he shared that having a refined perspective on who their audience is makes a huge difference.

“Define the audience when you pitch the book to retailers. If you notice, a lot of the creator-owned books that come out of the gate strong are the ones where you can look at it and see the potential for an audience.”

For creator-owned titles, it’s obvious that making a connection with retailers is paramount in achieving success, and if anything, it makes it clear that to succeed in this hugely competitive field, creators must be willing to take your work beyond the page.

Readers Still Matter, and More Than You Think

If I’ve convinced you that readers are a strangely unimportant factor in the success or failure of a creator-owned project, then I may need you to rethink that.

Yes, retailers are creators’ most important customers.

Yes, retailers no longer utilize pull lists to the same extent they did before for ordering.

But that doesn’t mean that you can’t help change everything for someone like Jim Zub, Frank Barbiere or Antony Johnston.

Ultimately, we’re all in this together, and you – yes, you – are the straw that stirs both creators’ and retailers’ drinks. Every day in our posts and tweets and ability to speak words in places that aren’t the internet, we impact the potential of a comic when we talk about it. As Anderson said, his staff is filled with comic book evangelists, and by being that yourself, you can change the future of a comic you love.

Think back to some of the things that were said above, and you can see that. At Jetpack, the amount of pull customers could add as many as nine copies being ordered of a new independent title to their shop, so if you do pull that title, it will still impact orders. For smaller books – meaning outside of Marvel, DC and even Image to a degree – many retailers won’t even order a single copy without your expressed interest. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to make sure that any book you know you are going to buy, you add it to your pull list or pre-order it or do whatever you can to tell your retailer, “I’m interested.”

In case you don’t know how to add something to your pull or pre-order a book, it’s simple, and Kieron Gillen even provides an excellent walkthrough on how to do it. More or less, it’s as simple as going into your shop, talking to someone that works there, and then asking them to add or remove books from your (assumably) already existing pull list. Some shops have online platforms that they use to allow users to control pull lists as well, and they may end up guiding you to it as a response. As part of this article, I went to my shop and updated mine to not just include the current books I am buying, but the upcoming ones I intend to buy. Those are both important considerations.

Beyond that, ultimately what decides the ongoing sales of a title – any title, not just creator-owned – is whether or not the copies a shop orders do in fact sell. If a retailer’s stock sits and ages and becomes back issue inventory, that is a book that will reduce in orders into oblivion.

That’s why above all, a reader’s role in this mix is to take action. Do you want a copy of “Umbral” Volume One? Buy it! Excited about “Copperhead” or “Wayward”? Pre-order them! Looking to try out “Rocket Girl?” Go to your shop and buy the first issue! Our action ultimately dictates everything for a retailer, which changes everything for writers and artists. Even you, random commenters on comic book websites. Your apathy or excitement is one piece of the puzzle that defines success for everyone involved.

Above all, in an industry where the difference between 12,000 copies sold and 8,000 could be what decides between prosperity and a comic no longer being financially viable, every little bit counts. Your approach to how you buy comics could make the difference between looking back fondly on what your new favorite book accomplished in its run and wondering “what could have been?”

Thanks to Antony Johnston, Brandon Montclare, Corry Brown of Zapp Comics, Eric Helmick of Bosco’s Comics, Frank Barbiere, Jay Faerber, Jim Zub, Patrick Brower of Challengers Comics + Conversation, Ralph DiBernardo of Jetpack Comics and Steve Anderson of Third Eye Comics for the help in putting this piece together.