Revisitor: On the Admirable Insanity of D.G. Chichester and Scott McDaniel’s Big Swing in Daredevil #317-318

Revisitor is a column in which I look back on comics from throughout history, whether they’re a single issue, graphic novel, comic strip, webcomic or basically any form of sequential art you can think of. When I do this, my hope is to include perspective from the people who made these comics – like I did with the debut edition about Mike Mignola’s Hellboy story, “Pancakes” – but that may not always happen. It did here.

Everyone remembers the grand epics from superhero history, the iconic works that enrich and define the tapestry of the genre. Whether it’s a finite series like Watchmen or an extended arc like Born Again, these are the moments fans point to time and time again as proof that superhero comics can be home to true greatness.

That’s understandable. Those are exemplary works. The only problem is, the vast majority of superhero comic history exists between those fleeting moments of transcendence. Many runs are filled with rarely recalled arcs amidst a few headliners, if the creative teams and readers are lucky. Achieving something memorable, let alone great, can be a struggle in the monthly grind. That’s why it’s worth celebrating these moments when they hit, wherever they reside. They may not be genre-defining works. But sometimes, they can be a whole lot of fun.

That’s the case for a two-issue Daredevil arc, issues #317 and 318, I recently unearthed during a visit to a local antique store. Don’t get me wrong: this comic from writer D.G. (or Dan) Chichester and artist Scott McDaniel will never be mistaken for an Eisner winner. It’s a bonkers story that preceded the team’s own epic, Fall from Grace, and featured an ensemble of villains you could generously describe as B-listers — including Stilt-Man, Taskmaster, The Wildboys, and more — on a furious hunt for hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of…restaurant grease. That’s right: restaurant grease. 1 But what it lacks in the traditional hallmarks of greatness it makes up for in sheer madcap energy. It’d be difficult to find many superhero arcs that go for it like this.

To your average Daredevil fan, this might have come across as the team having an ill-advised level of confidence in a strange premise. To me, though, it reads like a team trying something dramatically different with little concern for the potential response, something I both respect and appreciate. It reminds me of truly great bad movies, where the vision is there, it’s just done in a way that maxes out the strangeness. 2 This isn’t said as a negative either. I basked in the often-bizarre events of the story 3 all of which were approached with an underlying exuberance and pure, gonzo energy. This wasn’t just your usual arc; it was a zany one, filled to the brim with big, unusual choices. As a person who adores that stranger side of superhero comics, these two issues were for me.

Given that this story would be difficult for you to find, isn’t on Marvel Unlimited, 4 and is nearly 30 years old, let me give you a quick breakdown of my eight favorite elements of the arc to underline the sort of energy it brings to the table.

- The cover to #317 features one of Stilt-Man’s legs crashing through and breaking the Daredevil title, as Daredevil looks on in fear with the thought, “Ay caramba! Not him too!” 5

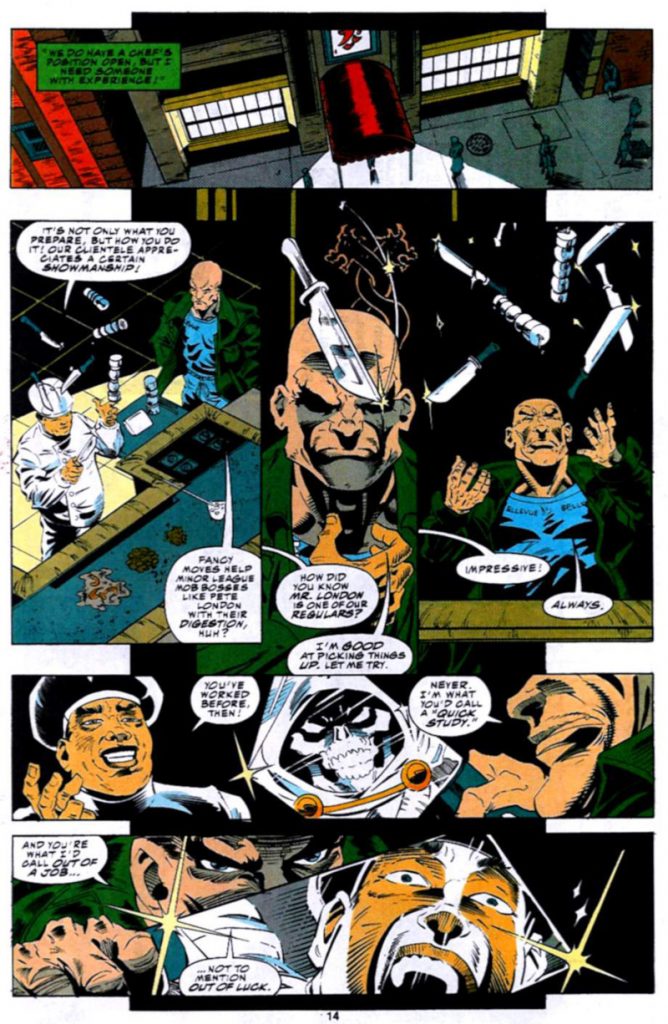

- Taskmaster goes undercover as a teppanyaki chef — a tough job with skills he quickly acquires with his photographic reflexes by studying an actual teppanyaki chef 6 — so he can get the inside track on the grease from a mob boss who frequents the restaurant

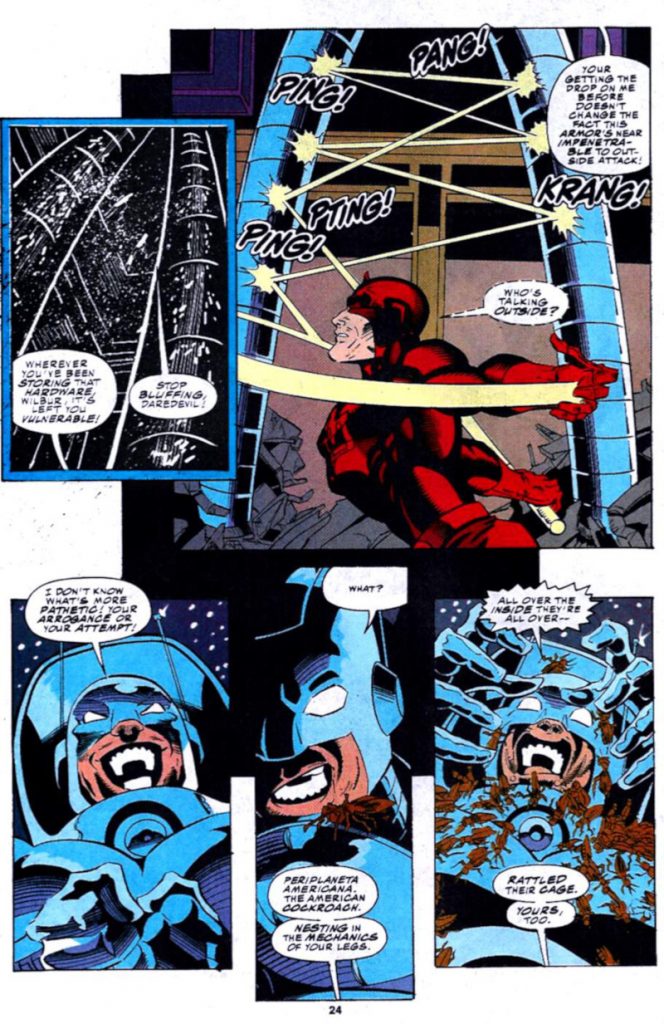

- To take advantage of this restaurant grease-based get rich quick scheme, Wilbur Day, aka Stilt-Man, has to reacquire his costume. During its time in storage, it filled up with cockroaches. This fact is later used to defeat Stilt-Man when Daredevil senses the roaches and vibrates the legs of the suit with his billy club, sending them swarming all over Stilt-Man’s face, simultaneously horrifying and overwhelming the villain 7

- Issue #318’s cover (and interiors) is so weird it legitimately has an “Editorial Disclaimer” on its cover to warn readers that they know the comic looks stupid, but they wanted to have fun with Daredevil before “we ruined DD’s life — AGAIN!”

- That cover also features a cockroach that speaks (in its own way) as the corner box art

- The bad guys are so bumbling that Daredevil eventually elects to guide them to the grease himself, that way he can make it easier (and safer) to stop them

- The villains are defeated when Stilt-Man slips in the grease, covering the bad guys in it in the process. This results in each of them getting stuck long enough to be arrested by the authorities

That might all sound silly to you. It does to me as well. But that’s what I appreciate about it. Daredevil’s history is rife with misery, an endless onslaught of tough times for Matt Murdock amidst even tougher foes. That comes with the territory, perhaps. His life is oriented around dealing with crime, a tall task for anyone. But crime isn’t always complicated plans crafted by evil super-geniuses. This arc confronts the reality of what the life of a vigilante might actually be like. Sometimes you get the Kingpin attempting to ruin your life (again). Other times you get Stilt-Man and Taskmaster battling each other over grease-based riches. Daredevil’s life should be ridiculous on occasion.

When I read these comics, though, one question kept ringing through my head: how the heck did they get made? This arc is that unusual. The cover to #318 and its editorial disclaimer suggested to me that everyone was in on it, though. This wasn’t some sort of inventory comic or one fueled by desperation because of deadlines. It was a palate cleanser. But still, I wanted to know more about this story’s origins.

So I reached out to Chichester, the arc’s writer, to talk to him about this admirably insane comic. And it’s worth noting that “admirably insane” was exactly how I phrased it to him. I wasn’t even sure if he remembered the arc, because for many, perhaps even the title’s own writer, it might have been lost to the sands of time. Thankfully, he found “admirably insane” to be an accurate descriptor of the arc and was happy to talk, telling me that the story “actually one of my favorites, in a divergent sort of way.”

According to Chichester, this story’s origins were rooted in two places: practicality and reality, two things that barely feel as if they exist within the arc itself. The latter was where the premise came from. The writer said his “main muse” on Daredevil was a New York City-based paper, New York Newsday. 8 He wanted the city to be a character in his run, so he’d go through the paper clipping stories about odd incidents as potential foundational elements of stories. One of those was about “grease thieves going across the city.”

“It wasn’t front page thing. I don’t even know if it was a page five thing. It was probably more like a page 35 thing,” Chichester told me. “But I came across it and it just stuck in my head 9 that grease could not only be a source of illicit profit, but that there was actually competition among thieves were going to steal it.”

Chichester realized there might be street level story in there for Daredevil. It only became what it was when he realized that the concept paired nicely with the plot of one of his favorite films, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, 10 and when fused together, it became a “scavenger hunt across New York City” featuring a gaggle of low-level Marvel villains. This story was born from that marriage of ideas.

The practicality side was more about its timing. Daredevil “wasn’t doing great in terms of sales” at the time, according to Chichester, so they needed something to “kickstart” the title. Fall from Grace, a sprawling, seven-issue arc from issues #319 to #325, was designed to do that. They needed an important, character-changing tale to move the needle in “the bigger Marvel attention sphere.”

The problem was, once they went down the path of destroying Matt Murdock’s life again, the viability of, say, a relatively innocuous, rather eccentric story of grease theft goes out the window. You can’t unring the bell of leaving Daredevil’s world in shambles, the team thought. 11 Chichester knew it was time for this story. That’s how this two-issue arc ended up as the story that led into Fall from Grace: it was a now or never situation.

Now he just had to build it out, which mostly meant determining its cast. Chichester found himself in a position where he needed a particular type of villain to fit its ensemble. There was an air of self-fulfilling prophecy to the arc, at least in terms of how the characters would behave. The writer admitted any villain would “degenerate” within its absurd confines, saying, “You can take Magneto and try to put him in the story, and he’s going to become a clown for two issues.” Still, he wanted to find the right fits.

Like with the origins of the story, his ensemble was partially rooted in practicality. Bigger names like Magneto would be difficult. Doing so would have involved getting permission from other offices at Marvel. He didn’t need to deal with that. More than that, those types would have been ill-fitting. What does Doctor Doom care about restaurant grease when he leads a country? 12 He needed characters that might actually care about a scheme like this.

“It’s more who fits the larceny aspect of it. Whose greed and avarice will allow you to play this out in the right way?” Chichester said.

That blend is where The Wildboys and the mafia types who play a part in the story came from. They were relatively low-hanging fruit as standard Daredevil foils. Stilt-Man’s involvement, though, stemmed from a flawless merging of concept and character, per Chichester: “Stilt-Man just came to mind because I couldn’t think of anything funnier than this 40-foot guy slipping on grease.”

The other two key players acted as contrasts to the rest. Chichester described Tatterdemalion 13 as a counteragent to the events of the story, someone whose “anti-greed, anti-vice” perspective created “friction within the group itself.” He needed a cast member to work against the villains that wasn’t a traditional peer or enemy. Tatterdemalion was the perfect wild card.

Conversely, Taskmaster gave the story an inkling of villainous legitimacy. My guy Tasky is a competent villain, with the writer describing the skull-faced character as “a terrifying presence.” Granted, he was destined to “become more comical” because of the nature of the story. But having a real professional amidst a gang of fools helped create a different flavor in the mix.

“Taskmaster fit within that because he continues to play himself pretty straight throughout,” Chichester said. “But he can’t compete with the ridiculousness of it.”

Some might question Daredevil’s fit in all of this. “Ol’ Hornhead in a comedy filled with B-listers? No way,” you might be thinking. I would disagree! As I noted, sometimes vigilantes can’t choose the crimes they have to deal with. Sure, the villains were “clowns,” as Chichester told me. But Daredevil was “the ringmaster of the clown circus for that bit of time.”

“And that’s what’s fun about it, I think,” he added.

Once the writer had the cast together, one that stayed within the street-level world of Daredevil, it all started to make sense. Chichester told me it started “to gel and create its own ridiculous conflict” from there. As he explained his plan for the arc, though, he noted that it sounded “much more intellectual than it actually was.” The reality was, he felt much more trepidatious about it. He remembers thinking, “’This is ridiculous. Are we going to get away with this?’”

Two things helped make the arc work as an absurdist tour through the lowest tier of Daredevil’s rogues gallery. One was artist Scott McDaniel’s commitment to the bit. Chichester was highly complimentary of the artist and the way he embraced the insanity. This was before the artist took on an acclaimed run on Nightwing at DC, and his time on Daredevil showcased many of the same strengths, with agile action sequences and solid character work. But it also allowed for visual comedy, something that was rare for McDaniel. He excelled at it, with Chichester saying the artist was “all in on the goofballness of it,” noting that McDaniel’s art “really enriched the characters and the moments.”

The other was how everything was fundamentally built from the characters. While Daredevil leads the way, these two issues were defined by a supporting cast that just isn’t very good at being bad. The titular hero mostly manipulates them throughout the story, putting them in a position to defeat themselves in fitting ways. Chichester determined those methods by digging into the characters’ histories, exploring the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe entries for each to suss out how they would handle the situation. That’s where highlight reel beats like Taskmaster’s immersion as a teppanyaki chef came from: it’s just the kind of thing the guy would do. 14

Stilt-Man’s defeat by cockroach, on the other hand, came from a mix of the extraordinary and ordinary. Chichester wondered what might happen if Stilt-Man hung up his “fairly fantastic” stilts in storage for a while before coming back to them.

“You’re in New York City. I lived in New York City forever and a day,” Chichester said. “You could not get away from cockroaches, no matter how clean you tried to keep the place.”

That’s where the strength of the story comes from. Yes, it’s one of the most bizarre Marvel stories I have ever read. And yet, so much of it is fundamentally built from basic, believable ideas of these characters. It almost reads as a confrontation of how weird all of this Marvel business — the superheroics, the schemes, the stilts — really is, having a laugh while staying mostly faithful to its cast. 15 It was like Chichester recognized the inherent absurdity of this world and simply chose to lean in for two issues. I had a great time reading it. That was not the case for everyone, though.

Chichester long struggled to look back on his time at Marvel. He said he had a “very poor view of (his) work,” and rereading it “felt like I was returning to the scene of the crime.” It made his relationship with it mixed, to say the least. In recent years, though, the writer said people 16 reaching out allowed him to see that his work did have an impact, and that maybe he didn’t need to distance himself from it so much.

The writer could look back on this one fondly, though. He described Daredevil as a “deathly serious” character most of the time, and with his run taking place during the 1990s, it was doubly grim considering the tone of the decade in superhero comics. 17 But he knew the character was capable of more — perhaps even taking part in a fun romp. This allowed Chichester to play with that.

“To go off the deep end with something like this was just a place to test myself and also to show that the character had the latitude to do that,” Chichester said.

Again, I’m not going to pretend like this arc was the greatest gift in the history of superhero comics. I described it as “admirably insane” for a reason. It is a massive swing, and one that absolutely would not connect for every reader. 18 It is not the traditional vision of a good comic. But if I had to choose between random arcs in the genre going for it or playing it safe, I’d say swing away every day of the week. After all, not every story is going to be a Watchmen or Born Again-level classic. Some, like this one, just exist on the margins of one of the most beloved titles in comic history. It isn’t going to compare to the legends that surround it. But it is fun and memorable.

And for some, that’s good enough.

More on that later.↩

Shouts to Sleepaway Camp, the G.B.M.O.A.T..↩

Which, of course, was made easier for yours truly due to the presence of both Stilt-Man and Taskmaster.↩

Which I find hilarious and not likely an accident. A chunk of this run isn’t. Issues #312 to #318 are nowhere to be found. Apparently even Marvel wanted to look past this story.↩

Which, presumably, is a nod to Bart Simpson’s usage of “ay caramba” from that period, the apex of Bartmania.↩

Who he then ties up so he can steal his job, before the chef breaks free an issue later and attacks Taskmaster while half-naked.↩

He later crashes into a nearby apartment and is sprayed with some sort of roach-killer by the tenant.↩

Which itself was an offshoot of the Long Island-based Newsday.↩

He apologized for “stuck,” which was an accidental grease-based pun. Between the two of us, grease-based puns became a slippery slope during our Zoom call.↩

There’s a nod to the movie in the credits for issue #318, in which each creator is labeled as a different actor in the film.↩

I should note: history suggests that you absolutely can, because it has happened so, so many times.↩

One that presumably has its own restaurant grease.↩

A character I straight up did not remember who has superhuman strength and a burning touch.↩

I have long advocated for Taskmaster’s powers being used in more comedic ways. Chichester was decades ahead of the curve in that regard.↩

The only beat that throws me off is one from #317 where Murdock is changing into his costume in front of Ben Urich. He drops a line that might have been a step too far down the insane train for me.↩

Like me.↩

This was the period where DC was killing all of its characters, for example.↩

Chichester knows this because he saw the letters. Fans were not thrilled about there being a comedic arc of Daredevil!↩