The Comics That Made Them with Chip Zdarsky

Let's dig into the origins and inspirations from comic history for one of the medium's best writers today.

An idea that comes up a lot on Off Panel, my weekly comics interview podcast, is one that’s been attributed to former DC President Paul Levitz — despite little evidence that it was actually him who said it. It’s come up a bevy of times, and it’s been specifically noted as coming from Levitz enough that I believe it. More than that, the concept still seems sound regardless of its origins, and that’s just because it feels right. “What is it?” I’m sure you’e wondering. “What is this Greater Levitz Theory of Comics?”

It’s this: the comics you love when you’re 13 are, effectively, the building blocks for what you’ll love going forward.

While that period isn’t everything for you, it does form the foundation of a lot of what you look for and connect with in the medium going forward. And not just the comics, but the comic-related media, from movies and animated series to trading cards and video games. While the comics are obviously the heart of all of this, I’ve talked to enough people with origins connected to every non-comic superhero project in the late ’80s and early ’90s to know that’s part of the equation for many.

I’ve always wanted to dig into the comics that were hugely inspirational, influential, and just beloved by our favorite creators when they were starting out with the creators themselves. 9 And that’s what’s launching here with The Comics That Made Them, an obvious play off the Netflix series The Toys That Made Us, 10 but with this edition being more hyper specific to individual tastes — thus the “Them” instead of “Us.”

And my first guest for this feature interview is cartoonist Chip Zdarsky, someone known for success within superhero comics and outside of that world altogether. In titles like Sex Criminals, Daredevil, and Stillwater, Zdarsky went from a fan-favorite artist to one of the most renowned writers in the medium today. He’s gone back to his roots as of late on his Substack, as he’s unleashed Public Domain on an unsuspecting world, merging his two hats into one super hat that proudly says “Writer-Artist” on it. But what comics helped ignite his love of the medium? Chip and I hopped on Zoom recently to find out, as we spent an hour or so discussing five comics and/or runs from comic book history that played a huge part in helping him determine the types of stories he wanted to tell. It’s a fun, sprawling chat about some great comics.

The hope is, like with all of these endeavors, that this semi-recurring column becomes just that: semi-recurring! But even if it’s just Chip, it was fun while it lasted. Give it a read below, and hey, share the five comics that (or comic-related materials) that formed your foundation in the comments. I’d love to hear them!

Also, as a note: this interview has been edited for clarity.

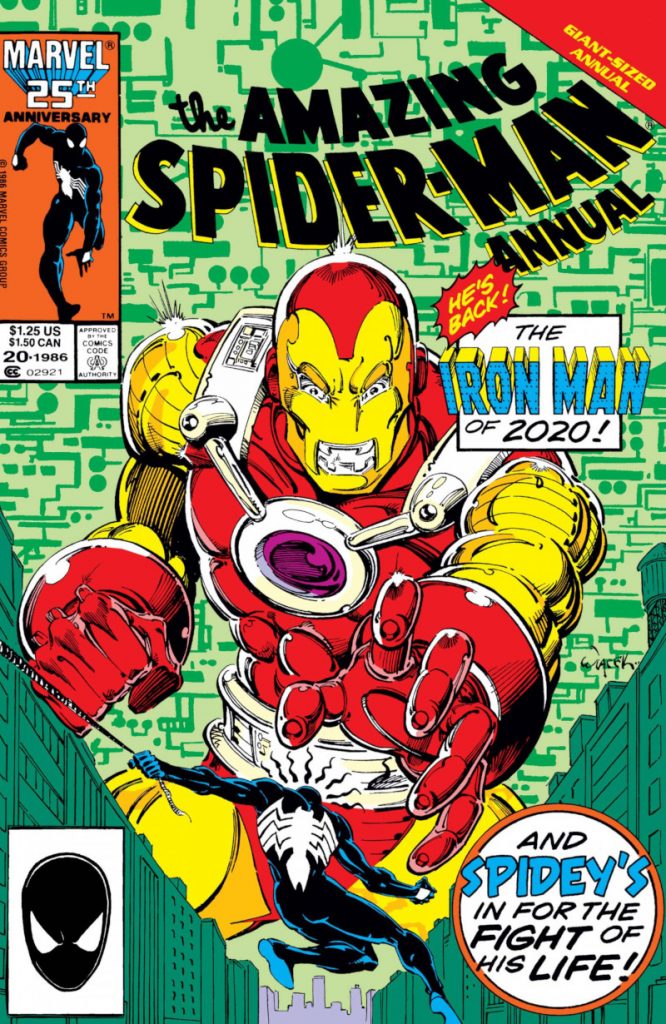

I want to start with Amazing Spider-Man Annual #20 from Fred Schiller, Ken McDonald, Mark Beachum, Bob Wiacek, Bob Sharen and Jim Novak making the cut. I had never read this comic before. I also don’t think I’ve ever even heard anyone mention this comic before. So, it was definitely the one that was the most out of left field. Where did this one come from?

Chip Zdarsky: I was collecting Amazing Spider-Man around that time. So, if you’re collecting a comic, you have to buy the annuals. That was always a real hit-or-miss proposition. Still is, because sometimes they’re cool done-in-one stories. Sometimes they’re terrible crossover things. And other times, they’re forgettable and just need to make their monthly budget. I remember picking this up and being like, “Yeah, sure, Spider-Man, fine.” And after reading it, I was just blown away. Looking at it now, it’s a basic time travel story featuring Iron Man 2020, which is very funny to me now. It doesn’t take place in 2020. It takes place in 2015.

I didn’t know anything about the character. I think the character only showed up once before. 11 I remember just loving the story and loving the art to the point where I was actively tracing images from it. Mark Beachum is an artist who, I hesitate to say nobody knows him, but I think very few people do. I don’t think he did a lot. And after telling you about this issue, I sought him out, and his Twitter feed is mostly Wonder Woman with her tits out, so things have changed. I guess he did a lot of Penthouse Comix and stuff like that. You can tell with his drawings of women in this. He’s got a Marc Silvestri vibe. I’d be interested to know if Silvestri actually knows his work because the women have the same proportions and shapes of late ’80s, early ’90s Silvestri.

But yeah, it’s one of those issues and it’s beautifully drawn. Amazing cartooning. As a kid, you love a thing, but you don’t quite know why you love it. You don’t take it apart. But reading it now as an adult, I’m just like, “Oh, no, this is actually just an amazing comic just on its own.” Because it does some bold stuff for a Spider-Man story. Spider-Man doesn’t show up until 12 pages in, I think?

It’s almost halfway through the issue. 12

Chip: Almost halfway through the issue, and you’ve already got such a great sense of Arno Stark, who is Iron Man 2020, in this. His family, his ego, his situation. It feels almost like a stealth pilot, as they would say on TV for a spinoff. You kind of expect an Iron Man 2020 comic after this except the way it ends is horrific, which also appealed to me as a kid.

Looking at it now, it’s such a well fleshed-out story for Arno Stark as a character. You understand him, and there are so many good parallels with Tony Stark’s military background as well. Then once you hit the Spidey stuff, it’s just classic Spider-Man. There’s a great Jonah scene. He’s got a classic Aunt May conundrum. It just checks off all these boxes. At the time he has his landlord, Ms. Muggins, who is always looking for the rent, and there’s such a funny scene of him just being like, “How am I going to get by Ms. Muggins? Oh, I know.” And he walks down the hallway as Spider-Man, which is just such a perfect Spider-Man/Peter Parker moment.

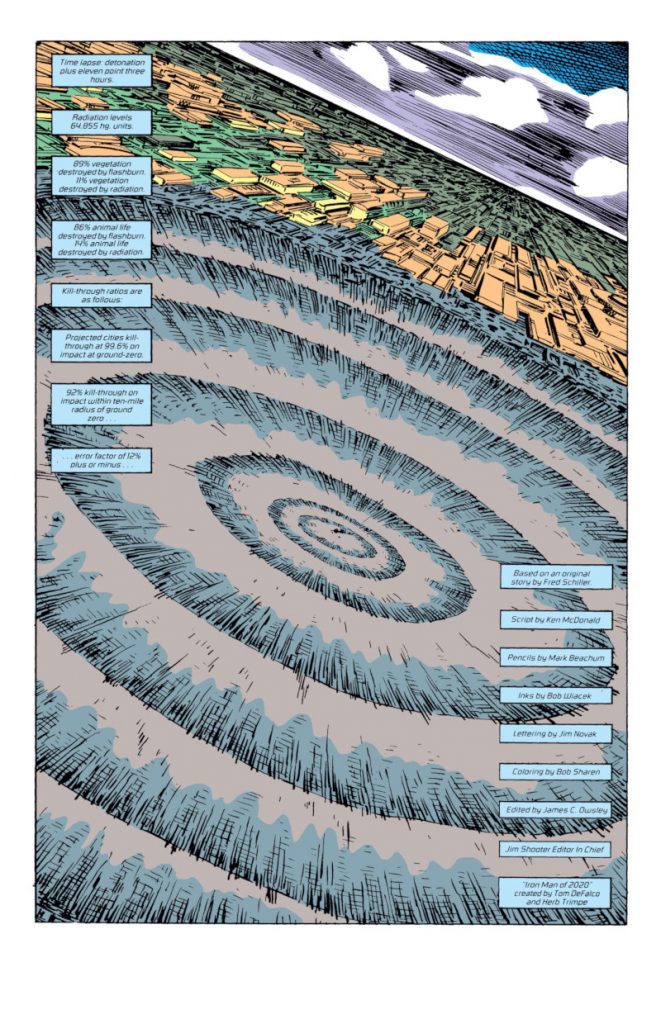

Then the time travel. Iron Man 2020 is trying to get the retina scan of the kid who is going to grow up to become a terrorist (who sets a bomb) so he can save his family. And there’s also that amazing Spidey problem where Spider-Man is the reason the retina scanner gets wrecked, (which means) Spider-Man is inadvertently endangering this kid even more. Also, another great Spider-Man moment is when the kid gets hurt as Spider-Man is trying to escape. You have that bit that I think every Spider-Man writer wants to come back to, where he’s just like, “You hurt a kid!” and he just goes off and beats the ever loving shit out of Iron Man 2020. I’ve always been drawn to those moments, especially with that character.

Another ’80s Spider-Man issue I almost suggested was where he fights Firelord, the herald of Galactus, where it’s just two issues of him running away from Firelord and then finally having it and then beating the hell out of him, which shouldn’t be possible. 13 But, it’s such a Spider-Man thing. He’s a joker and he’s hard luck, but he’s actually the strongest character that Marvel has on hand at any given time.

As a reader, you know Iron Man 2020 needs to get this info. He needs to get this kid back to potentially save his family. So, Spider-Man’s doing this thing that’s wrong but also right. There’s so much conflict in that, and it’s really well done. The end result is Iron Man 2020 failed, and he caused the terrorist (to happen) inadvertently, which results in him setting off this giant bomb, killing a bunch of people.

A lot of people.

Chip: It’s a really well done done-in-one, which is always the holy grail of comic writers and artists. To tell a solid single-issue story. And we don’t… I was going to say we don’t get a lot of chances (to do that), but I don’t think we give ourselves a lot of chances as comic creators to do that.

Everyone wants to tell an arc.

Chip: Everyone wants to tell an arc. I mean, rereading this just made me realize that, “Oh, man, Marvel and DC should just devote their annuals to really good done-in-one stories, give them the space like this.”

There are so many great Mark Beachum drawings in here, beautiful gestures, beautiful expressions and solid layouts too. It’s a shame there wasn’t a lot more from him in mainstream comics.

I do want to say that I wasn’t surprised by the pick because it was bad or anything. It’s a great comic. I was surprised because it’s so good that that I can’t believe I never heard of it. And then on top of that, it’s the people involved with it. It’s a lot of people who never really did much past this, but it’s still an exceptional done-in-one story. That’s rare. But I’m trying to flash myself back to when you first read this. How old do you think you were?

Chip: What year did it come out? It was 1986. I was 10.

So, you’re 10. You’re buying this; you’re reading this comic because you’re excited about reading a Spider-Man comic. You effectively read a 40-page comic about Spider-Man being the bad guy for this future story, which is really such a fascinating thing to read from Marvel, especially through today’s prism where quite often Marvel doesn’t want to make their good guys seem like bad guys. This made me wonder where this fits in the timeline. He’s wearing his black suit. And regardless of what Iron Man 2020 was doing, let’s just say Spider-Man goes too far.

Chip: I know. But it’s still Iron Man chasing down a kid.

Exactly.

Chip: And acting so out of character. So, Spider-Man, he’s still the good guy in this. He’s still protecting and helping. But he just doesn’t know what the reader knows. That’s such a great storytelling technique, just keeping the reader in the loop on a thing that the main character doesn’t know. So, you don’t know who you want to succeed here. It’s so well done. There’s also a moment towards the end when the kid is in the hospital and suddenly, the kid’s dad offers Spider-Man a reward. And it’s like, thousands of dollars, versus whatever Spider-Man asked for.

It’s like $419.76 or something.

Chip: Yeah. It Was $275.

Oh, $275.36, that’s it.

Chip: Just enough to pay Mrs. Muggins. It’s such a great Peter Parker beat. I will say this…I have to be a little careful here. But the story and the writer, it’s by Fred Schiller and Ken McDonald. At one point at a convention, I was talking to an old-time Marvel/DC guy. I don’t even know how we ended up getting onto the subject of this annual, but it turns out this guy wrote it, and it’s not the name that is on the comic.

Interesting.

Chip: So, it’s one of those things. If I had to piece it together, I’d say someone named Fred Schiller came up with the story and probably didn’t deliver, so they brought somebody else in, but they wanted to use a different name. What did directors use (to hide their participation in a project)? What’s the director name?

Alan Smithee.

Chip: Yeah. Alan Smithee. It was like an Alan Smithee kind of thing. It’s like, “Oh, just put this name on it.” I can’t reveal who it is because I don’t have permission. But it’s one of those things where it was so shocking for me to be in front of the person that actually wrote this story. I was just like, “Oh, my god, it’s like one of my favorite stories,” and it’s uncredited to this writer.

I have to say, that explains why I have no idea who he is. He’s not a real person!

Chip: I think this is the only credit for Ken McDonald, and I think there’s a few for Fred Schiller. So, I don’t know what the full story is behind it. But yeah, it reads really well because it was written by an excellent writer, I’ll say.

I love that Spider-Man just thinks this is the Iron Man of his time rather than from the future. It’s probably because Iron Man changes his armor so much. Spider-Man is just like, “Whatever, it’s just a new armor.” That’s just what he’s got going on. It’s totally believable.

Chip: Yep, and the action doesn’t slow down enough for him to actually interrogate what the problem is.

That’s a real Marvel storytelling thing where things are just happening so fast, so there’s always the confusion that leads to the tussle. It’s a really solid issue. As a kid, I knew it. But I didn’t know why. As an adult I’m like, “Oh, there’s a lot in here that’s amazing.”

There are two things I want to point out about it that I think are really funny. One you already mentioned. It is hilarious that on the cover it says Iron Man 2020, and then on the next page it’s like, “The year is 2015.” And you’re like, “Wait, what?! Why?!”

Chip: I don’t know if it’s because it contradicts the story before because I don’t know enough about Iron Man 2020. I never read anything before or after about the character.

I also love the fact that when he lands in his facility, he’s got roller blades that come out of his boots. The funny thing is that roller blading is seemingly popular again, at least in Alaska. So maybe they were on to something. They knew it was going to come back. But it sounds you would like to do more done-in-one stories. Do you think this has affected you as a storyteller in any way? When you think back on it, maybe it changed what you want from your own stories?

Chip: I can’t pick anything specifically out of this. Just the fact that as a kid, you buy a lot and you don’t have a good sense of what’s good or bad, and this is one of the first times where I was like, “Oh, this is good.”

And especially good in a way that doesn’t affect anything, which is a problem I have now and everyone has now, which is you can write a great story and everyone will be like, “Well, how does this change things?” “Well, it doesn’t. It’s just a great story.” And that’s the case here too. Spider-Man is not a changed character at the end of this. Iron Man 2020 is. But nobody cares.

Also, his home has definitely changed because it doesn’t exist anymore.

Chip: Oh, god. So good. Yeah, I don’t know. There’s probably a subliminal, unconscious effect that the story had on me.

But nothing specific you can point to?

Chip: No, nothing super specific. Just the love of a good done-in-one story.

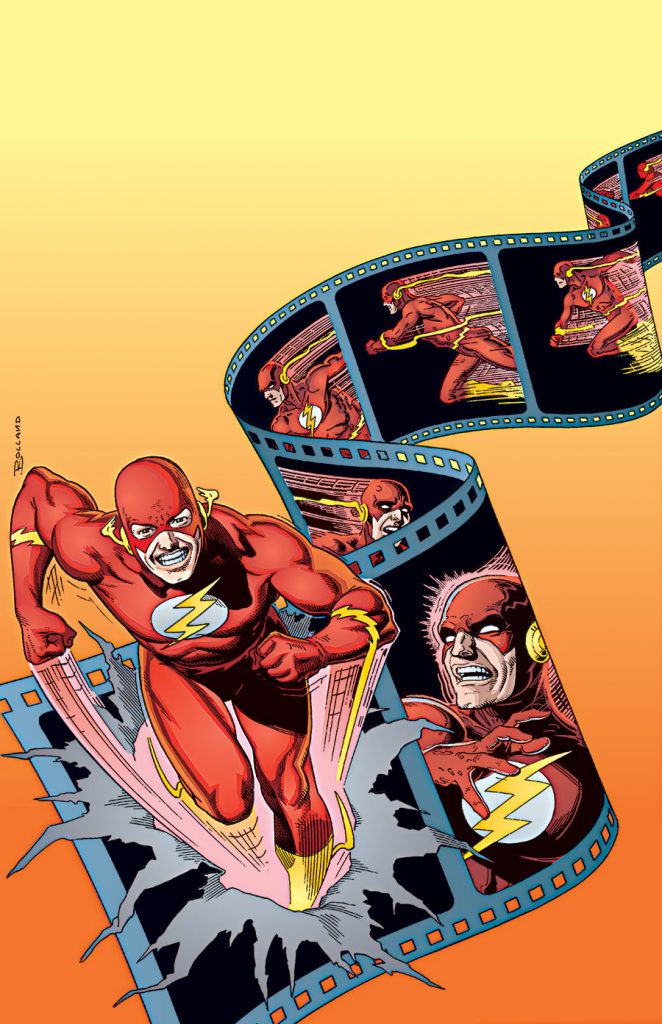

The next one we’re going to go over is an easy one for me because this was one of the first trades I ever bought. It’s The Flash: The Return of Barry Allen from Mark Waid, Greg LaRocque, Sal Velluto, Roy Richardson and, shockingly, Matt Hollingsworth coloring. I did not see that coming.

Chip: He gets around.

He gets around. So, what’s your background with this? Were you a Flash guy when you were growing up?

Chip: Yeah. I think out of all the DC stuff, Flash is my go-to. As a kid, I first started reading DC with The Trial of Barry Allen. I convinced my little brother to collect DC while I collected Marvel, so I could also read the DC comics. I also convinced him to let me hold onto his books because they were so valuable and he would just wreck them. So I was a terrible, terrible older brother forcing him to buy comics for me to own and read.

So yeah, I really got into Flash during that period because the idea of a superhero on trial was mind-blowing. Then, post-Crisis, I remember picking up the first couple of issues of Flash drawn by Butch Guice, who I got to work with on Invaders, which was a super thrill for me. I remember really enjoying those issues, but I dropped off them. I would pick The Flash up every once in a while, especially later on when Greg LaRocque came on board. It was William Messner-Loebs who was writing, and there was some fun stuff in there. But when Mark Waid took over, I just fell in love with the book. The Return of Barry Allen arc is so tight. I think it’s only four or five issues, right?

It’s #74 through #79 from that Flash run. So, I guess it’s six?

Chip: What I loved about it was the surprise. Mark was really good at surprising the reader, which I think at that point… When did it come out?

It was released in ’93.

Chip: I was probably 16 or so, and I was kind of getting out of the superhero comics at that point but mostly because I found it predictable. Same old, same old. But with this, every issue had another surprise and ramped it up so much over the arc that it blew my teenage brain. And Mark Waid became my favorite writer right after that.

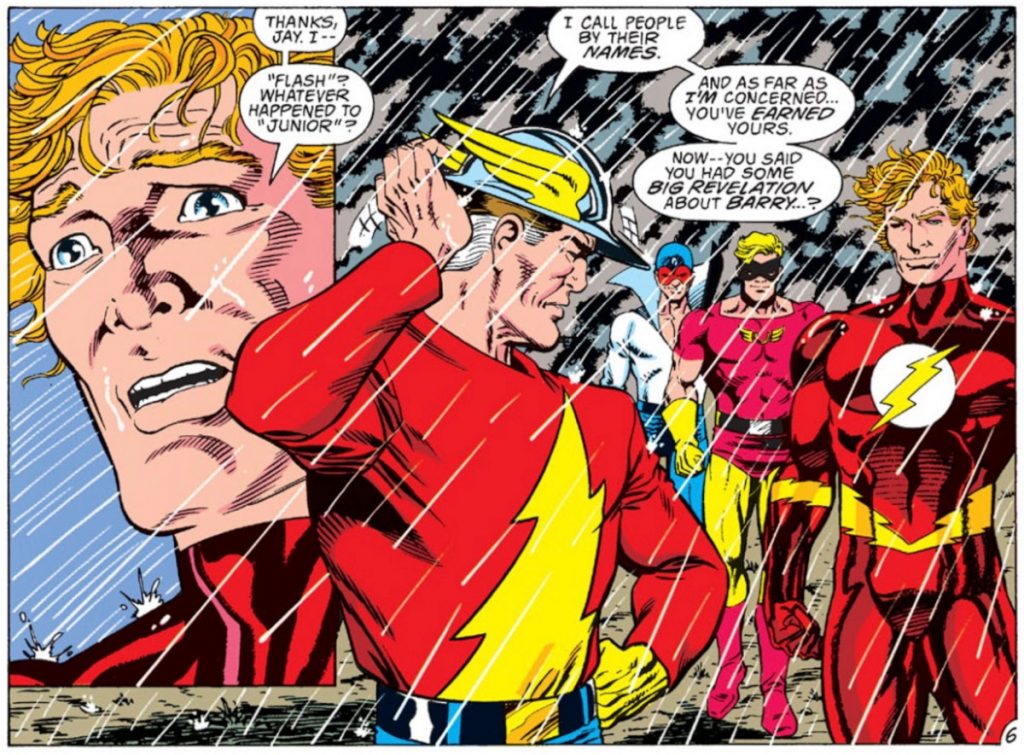

I don’t remember when I actually got into it. It wasn’t 1993. But I’ve always loved Wally West, and it’s interesting because how Waid makes it both about the return of Barry Allen but also about Wally West taking Barry’s place, something he doesn’t feel he deserves. But this reveals to him why he does deserve it. It’s just so well done. And the way that Mark works in all the other speedsters, like Jay Garrick and Johnny Quick and Max Mercury. The whole beat about them not calling Wally Junior anymore and starting to call him Flash, there are all these really smart things that Mark does in the book that just really, really work.

Chip: We’ve seen legacy characters and a passing of the mantle before, and it’s usually reset, right?

Right.

Chip: But with this, it felt like, “Oh, this is the opportunity for him to no longer be Junior or a Kid Flash wearing the Flash costume.” It’s him leveling up and becoming the Flash. And they do it by tricking the readers who wanted Barry back by presenting Barry and then taking it away like that, and yet still achieving the goal of making Wally a stronger, better character at the end. I think everyone reading that at the end, even if you were a Barry Allen fan, you were like, “Oh, this is the Flash.” Then bringing in the other speedsters too and having them teach Wally their tricks and just showing that Wally can be the best of them, it was an important step in the series. I love it.

I’m trying to think of how traumatized Barry Allen fans were by this arc, as they’re reading him become a villain and not understanding why because… I mean, I don’t even want to spoil this in case somebody decides to read it for the first time, but all is not as it seems. When you’re reading it, it’s just, “Wow, Barry Allen got dark.”

Chip: It’s believable as you’re going through it, too. You’re just like, “Okay, I could see this.” I was a Barry Allen fan. I started with Barry Allen and I liked Wally, but having Barry come back was really cool. And then your heart sinks as things go south. Mark did this really smart thing too by bringing him back at the end of a Christmas issue. He really made it so you believe it.

He doesn’t just show up. He shows up at the door as a Christmas miracle. That’s a shitty thing for Mark Waid to do to us. But it works so well.

I think it’s funny that the first two things we’re going over are time travel stories. There are time travel stories that aren’t so rote in their approach. That’s one of the nice things about the Flash though. A lot of speedsters can travel through time, so you can do things like this in a way that fits within the parameters and the timelines of the overall story, like with the eventual reveal of who Barry actually is and where it fits into the overall story. It’s just so smart. I haven’t read a lot of the Barry Allen stuff. I’m the opposite of you. I am a ride-or-die Wally West and Bart Allen guy. But, at the same time, it fits really well within the story of the character it ends up being.

Chip: I’m kind of a ride-or-die Wally guy now. It was that run and that storyline and then (artist Mike) Wieringo coming on board. That really amped it up for me. I did Justice League: Last Ride recently and DC was like, “Oh, just use whatever versions of whatever characters you want,” like, out of continuity. So, putting together my Justice League team, I was like, “Well, it’s Wally, he’s the Flash.” You don’t need Barry Allen as the Flash. You don’t need another strait-laced dude there. And it’s not like current Wally either, because he’s been through a lot. I want the jokey vibe of a younger Wally if I’m making a Justice League team.

It’s interesting to see writers gravitate towards Mark Waid’s era sometimes when they get tell out of continuity stories. I forgot what the name of it was, but Tom Taylor wrote a DCeased digital series. 14 One of the stories was just this one-and-done digital story about Wally West trying to save the world from everything that’s going on. I would argue that it is actually written as an ending to Mark Waid and Humberto Ramos’ run on Impulse. It has Max Mercury in it, it has Jesse Quick and it has Bart Allen in it. And it’s really interesting because I think that Geoff Johns’ run is probably more beloved by fans, but I would say that a lot of writers I talk to, Mark Waid’s run on the Flash was very formative, especially with Wieringo and everyone else on it.

Chip: I mean, it also depends on what age you were when you read it.

Absolutely.

Chip: I recognize that too. Subsequent runs may actually be better in quality but you have a soft spot for the stuff you grew up reading. And so, with Waid’s run, and actually almost all of Waid’s work… I was talking about his FF stuff recently because, shout out to your competitor Newsarama, who did the oral history of Waid and Wieringo’s FF run. It’s Tom Brevoort and Mark talking about how it happened, behind the scenes stuff, and what they set out to do. Waid was so good at setting a thing up and then surprising you.

For example, he had a whole thing with Doom’s lost love, and it helps you just kind of have this soft spot for Doom in the story. Then it turns out he’s just getting her to love him again so he can use her soul and their love as a bartering chip with demons in hell. It’s such a great Doom thing, and he does the same thing here. I aspire to that. I’ve attempted it here and there in my work, though never as well as Mark has done.

I’m sure you’ve probably talked to Mark about how he approaches things, but I talked about this stuff with him before, and he told me that he likes putting himself in a corner that he has to find a way out of.

Chip: I know. That’s crazy.

You can see it in the work. I remember talking to him about this one issue of Impulse, in which the issue ends with a car driving off of a cliff. We talked about how he did that. And he was like, “Yeah. I wrote that without knowing how they were going to survive that.” Then when he wrote the next script, he had to figure it out.

Chip: I half buy it. I think there are some issues where he does that. But there’s no editor who would allow that. An editor wants to know where you’re going. You can’t just be like, “Let’s run an issue where he dies at the end. Who knows what happens after that?” You need a bit of a game plan.

Yeah, absolutely.

Chip: Especially like the Barry Allen thing. I’m pretty sure he didn’t just go. “Okay, and Barry Allen shows up at the door. We’ll figure out what happens next.”

Maybe it’s situational.

Chip: Exactly.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

These aren’t just the comics they read when they were 13. Just ones from earlier in their lives that made a real impact.↩

Or The Movies That Made Us, if you prefer that flavor.↩

1984’s Machine Man #2.↩

16 pages in on a 40 page comics, so split the difference between what Chip and I said.↩

This was in Amazing Spider-Man #269 and #270.↩

That’s Hope at World’s End.↩

I’m holding the Born Again Artist Edition as we talk.↩

This is issue #266.↩

These aren’t just the comics they read when they were 13. Just ones from earlier in their lives that made a real impact.↩

Or The Movies That Made Us, if you prefer that flavor.↩

1984’s Machine Man #2.↩

16 pages in on a 40 page comics, so split the difference between what Chip and I said.↩

This was in Amazing Spider-Man #269 and #270.↩

That’s Hope at World’s End.↩