The Comics That Made Them with Cliff Chiang

The comics you read and the comic experiences you have early on in your life often form the building blocks of your relationship with the medium. Obviously what you’ll enjoy expands from there, but for readers, those early experiences can be enormously influential on you going forward. It’s the same for our favorite creators. Some of those foundational elements can define the interests or views of writers or artists in the future. This interview column is all about those, as I chat with creators about five of the biggest influences and inspirations from the time before they were working in comics. This is The Comics That Made Them.

Whenever this column is pitched to a creator, it’s a choose your own adventure setup. Each can pick whatever five comics, creators, runs, or comics-adjacent ideas that strike their fancy, and it can be from any point in their lives. They don’t have to be from their youth. They just often are, because those early days can be so crucial to our development as appreciators of the comic book medium.

Often, but not always.

That certainly wasn’t the case with writer/artist Cliff Chiang. When I pitched Cliff this idea as a follow-up to his phenomenal work on Catwoman: Lonely City — we already discussed that series extensively on Off Panel (but keep an eye on that hardcover that arrives next month), so I thought it’d be interesting to instead look at his roots as a storyteller — the five works he selected were building blocks for him as he started considering the medium in a serious manner back in college and as he was looking to break into the industry.

Armed with this quintet of fascinating selections, Cliff and I hopped on Zoom recently to have an extended conversation about how each of these — four of which are comics, but one of which is a short prose story — made an impact on him as a person and as a comic creator. You might be surprised by some of the selections. I know I was. But as you read this discussion, I suspect you’ll understand how each fits Cliff, and helped set one of the finest talents in comics today on the path he’s taken.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

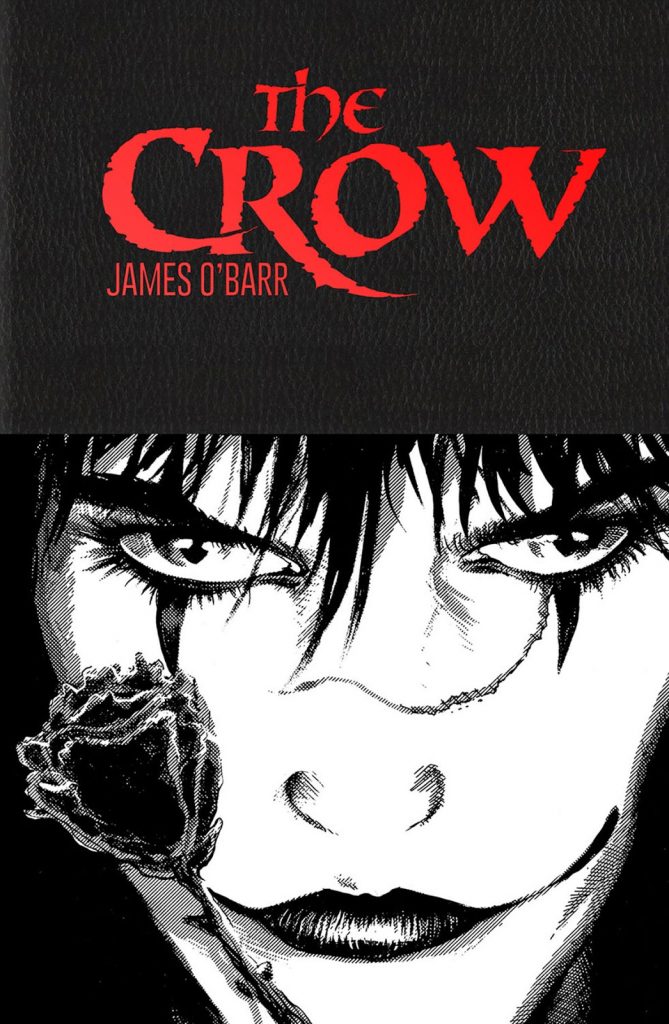

We’ll start with The Crow from James O’Barr. I’ll be honest, this was the one that surprised me the most from your picks. I had never read any of this before you had it on your list and I had never even really familiarized myself with its story, beyond the first movie. After reading it a little, in a weird way it kind of felt like the opposite of your work in the sense that it’s very grim, it’s very dark, it’s very tragic, it’s extremely inky. I only read the first volume, but I’m still kind of surprised by this one for you. What was it about this one that had made such an impact for you?

Cliff: I started to get back into comics in a big way when I was in college, after not reading them when I was in high school. I’d see The Crow on the shelves and wonder, “What the hell is this?” I was getting into more creator-owned comics with the advent of Image Comics and seeing that there was this wide range of material out there was really exciting. Suddenly it was like, “Oh, I don’t just have to read this Image superhero stuff. There’s other weird stuff. And look, this one is collected in a book.”

There were so many independent books that I didn’t know about, that had been coming out for years. Reading The Crow was really mind-blowing for me because there’s a lot going on with it. There’s the tragic backstory of James O’Barr. There’s the aesthetics of it which — being kind of a pseudo-goth, myself, being a fan of The Cure and Joy Division and all that stuff — I saw where it was coming from. It really spoke to me. I related to it. The design of The Crow is so iconic and it felt really underground at the time. The movie wasn’t out yet, they hadn’t announced any of that. So this was just your own little subculture that you could get into. Reading it opened my eyes to the idea of comics, even genre comics, being a valid mode of self-expression.

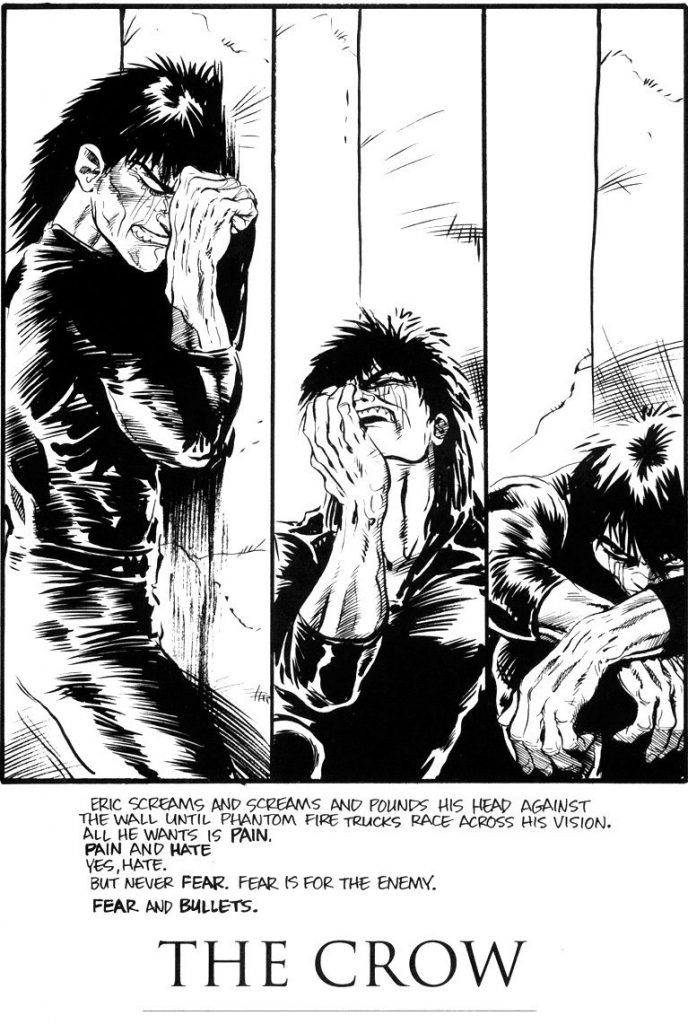

You can’t read The Crow and not think about James O’Barr. You can’t help but feel him on every page. I think some of the psychic trauma that he was going through comes out in the page and the way it’s drawn. The fact that it’s just black and white and very harsh is also part of it. It feels independent. There’s a vision here. Clearly an artistic vision too. It’s not just plot. There are pages of The Crow dancing solo, that you wouldn’t get from someone who’s just interested in showing him beat up gangsters. He’s really interested in exploring this story as a way of exorcising his own feelings of rage and sadness. Maybe I’m reading into it too much, but I feel like that’s part of the mythology of the book. And so I bought into it, for sure.

It’s such a strange book. It’s got this grindhouse feel to it, but then you flip the page and there’s a really delicate illustration with poetry sitting underneath it. It’s all so intentional. I hadn’t come across anything like that before. I think it’s probably by virtue of it being one person doing it all, too. That vision is coming through.

So, it just kind of rocked my world because I’m 20 or so at the time and this thing obviously speaks to me on an aesthetic level, because it’s stylish, because it’s alternative. This was 1992 or 1993 when I was reading it, and I was listening to bands from Lollapalooza, Nine Inch Nails, and industrial music. Going to college, being in Boston, trying to go to clubs and getting into music of all different kinds, it all dovetails with something like The Crow. Here’s a book where the creator could indulge all their interests in a way that isn’t just name dropping, but is really putting it into the work and letting it be a part of it. So it was surprising to me to see how much you could do with it.

When I was in college back in the early to mid 2000s, I was really into emo and screamo music. I feel like a lot of people who were young and read The Crow at the right time, I bet loving it wasn’t even about qualitative things in a traditional sense. It was about feeling it. I imagine it’s about the emotions a young person goes through in the same way that loving music from Lollapalooza or screamo was.

But you said that you might have been reading too much into it. You weren’t. Here’s something from James O’Barr that I came across. He said he went into The Crow looking for catharsis, but instead it only made him more self-destructive and that it resulted in, and I quote exactly, “Pure anger on each page.” You can feel that.

Cliff: It becomes this artifact of what he was going through. There’s a certain amount of voyeurism in reading it, where you feel him working it out on every page. It’s uncomfortable, but it feels authentic and grimy on multiple levels. And that’s just something that I hadn’t seen before in comics, the idea of doing something that is so fully realized in that way. I was just getting back into comics, and that really made an impression on me. My comics might not feel like The Crow aesthetically, but there’s something there. I recognized this desire to work out your emotions, to work out stuff in your head, to work out issues, through your art. And that’s the path forward, to get yourself to a state of grace, I guess, but also to exorcise whatever those artistic demons might be.

It’s worth saying that there may be no comic that has a more tragic backstory behind it than this one. It’s awful. It being inspired by his wife dying to a drunk driver is tragic, and this was him trying to sort that out. Even the movie and what happened with it, this entire idea is just permeated in tragedy. You can feel it in the work. Also, I do think the interesting thing about the book is, as you mentioned, there’s this intense brutality to it that can completely change on the next page, where all of a sudden he goes from killing some people to sharing a memory of when he bought his wife a cat. It’s beautiful and tragic and honest and sad.

I wanted to mention, obviously you’re not dealing with that level of tragedy in Catwoman: Lonely City, but you are still expressing yourself in the same way that James O’Barr was. You’re confronting something you’re feeling about modern society through your art, just maybe a little bit less brutally.

Cliff: Yeah, and this is the point of telling stories. To try and examine something that you are interested in or that you need to get out there and then hope that you do it in a way that is specific yet universal enough that other people can relate to it.

The last thing I wanted to bring up here is, it’s interesting that all the comics on your list are by cartoonists or writer-artists. Do you feel like that’s meaningful in terms of their inspiration?

Cliff: I think so. I think it’s possible, too, that I picked them because of that. It’s certainly tidier, but I was reading a lot of comics in this time period. It was me getting back into comics and then, within a couple years of that, deciding that I wanted to try and explore making comics for a living either in the industry as an assistant editor or hopefully, later on, as a penciller-artist-cartoonist. So these are the books that seem to have inspired that path more than others that I might have read as a fan but didn’t consider artistically in the same way.

That makes sense.

Well, let’s talk about one of the most specific artistic expressions you could possibly ask for, another one I actually have the book of. Mike Allred’s Madman. (David holds up a copy of the Madman Gargantua omnibus)

Cliff: Yeah, I just picked up this crazy omnibus (Cliff holds up a copy of one of the Madman Library Editions), because I have a bunch of these in trade paperback and I thought, “Well, what does a larger presentation look like?” and “Maybe I should have something in hardcover,” because they’re all kind of beaten-up.

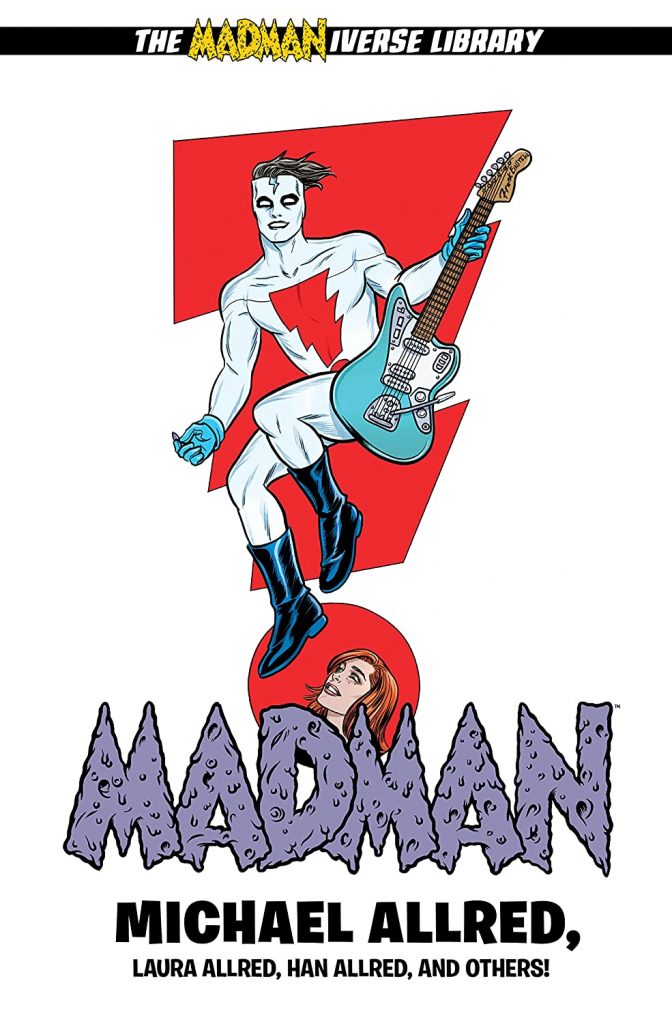

The interesting thing about Madman as an idea is that it’s translatable to the superhero concept. It has superhero elements, it has spy elements, it has sixties mod vibes. It’s just a pure expression of Mike Allred.

Cliff: It’s kind of the flip side of The Crow.

It absolutely is like the flip side of The Crow.

Cliff: Superhero stuff is only part of the pastiche. There’s so much of monster films and mid-century stuff and go-go dancing and this really wonderful mix of things going into Madman. I picked it up at the shop. I think there was, at that point, only the first Tundra collection. 4 And then the monthly series started coming out. To see somebody indulge their interests and their passions in their comic felt really pure. When you read it, you feel like you get to know Mike Allred somehow.

The character is so pure and goodhearted, and you’re just along for the ride with him. But there’s all this wacky stuff that happens and things that point to Allred’s sense of humor and what his interests are, as well as the spiritual stuff. There’s more going on than just a regular kid’s comic. Even though there’s this kind of gloss, this colorful sheen to it, there’s quite a bit going on with the book. I was a little late jumping on the train, so I tried to find some of the older stuff and then I was missing earlier issues of the monthly, which is the classic collector thing of making me want it more.

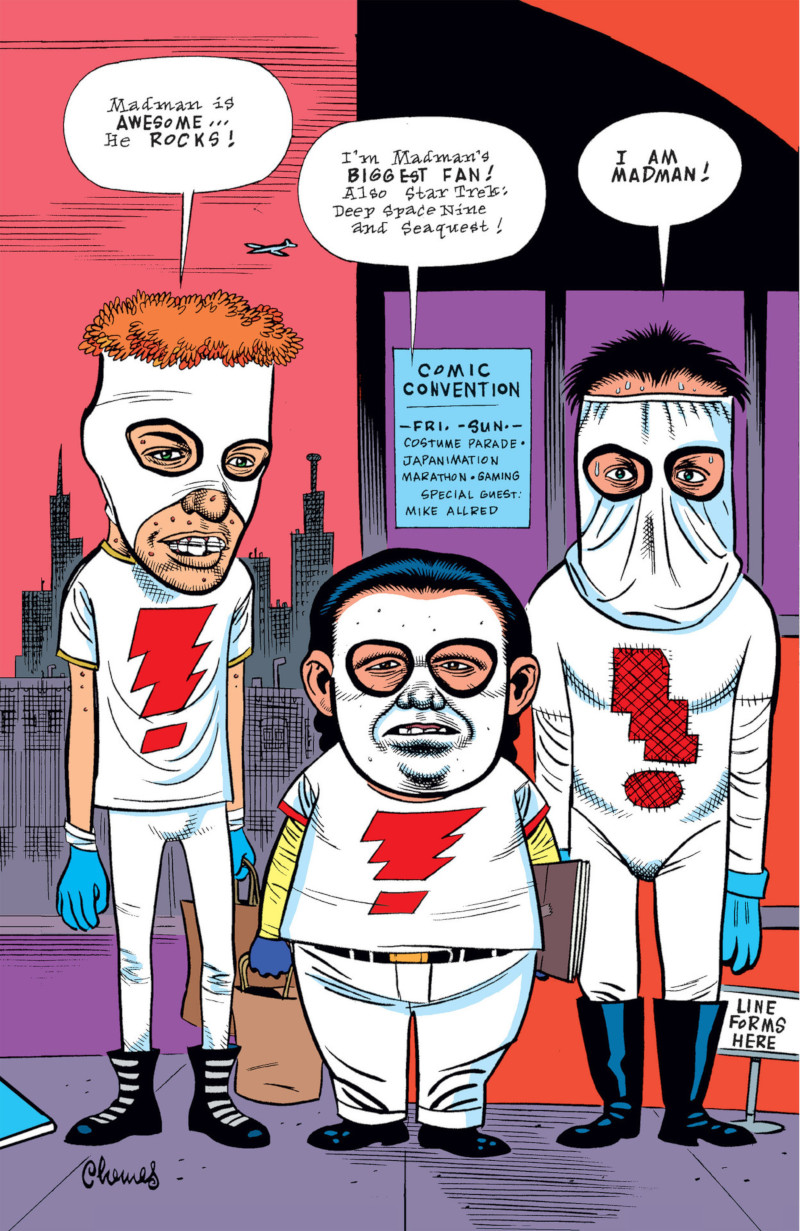

But I just really loved it as, again, another personal expression. And the great thing was, there was a letters column in the single issues. But in it, he would also spend a page talking about his influences and spotlighting an artist. And so, for me, getting back into comics and never having gone to a comic shop that regularly and not having had much of a community around of fellow readers, this was great. It pointed me towards other books. It showed me, “Oh, those SuperFriends cartoons that you liked, those were all designed by Alex Toth.” Or, “This Kevin Nowlan, I remember he did this cool issue of Moon Knight.”

It became part of my re-education in comics as someone who was interested in the art and following particular artists. As a kid I knew which artists I liked but was kind of too lazy to really think beyond that. Now I was free to buy and read whatever I wanted to. That letter column was such a gift. It was a gateway to seeing comics in a different way.

I think it’s simultaneously a gateway into Mike’s mind, but also, like you’re saying, in Madman Gargantua it shows all the pinups that were with each issue. The pinups in there are crazy. The first issue is Jack Kirby, then Frank Frazetta, Alex Toth, Barry Windsor-Smith, Moebius, Dave Stevens, Joe Kubert. Then go down the list and then you get into Chris Ware, Charles Burns, Los Bros Hernandez, Seth, etc. etc. It’s crazy. I imagine that some people who just picked up Madman on a whim might have been introduced to an entire world of comics that they had never experienced before because of it.

Cliff: Yeah, absolutely. All those recommendations, all those references to other comics and artists, they absolutely helped broaden my reading. I guess looking at stuff like Wizard will also do that and you’ll hear about what’s hot or what was going on at any given month. But this was curated by someone whose sensibilities I really liked and shared. So it was like having a friend or an older brother say, “Hey, check this out.” And it would be good and different and maybe not what you were expecting. I’m so grateful for that, and that was an extra thing from the main comic story.

I’m pretty sure the reason I started reading Madman was Wizard. It’s one of those books where I started reading with issue 15 or 20 or something like that, and then I kept reading it and spin-offs like The Atomics. It’s funny, before this interview, I’d never read the original story, the first three issues. Reading the first three issues was interesting because it simultaneously felt like Mike really knew what he wanted for it, but he only had it like…85% figured out. I feel like that was very nicely illustrated by the fact that Frank’s hair isn’t revealed until the final issue of the original series. I’m sure that was planned, but it feels like just as Frank is figuring out who he is, Mike’s figuring out what the book is in that first three issue miniseries.

Cliff: Yeah, it’s an incredible record of growth because you see the first series and it’s great, but just the process of him learning how to write and draw and what to do with this story is incredible. And then when you get to the monthly, it all suddenly gels. In Gargantua those first three issues are black and white, right?

They are, yeah.

Cliff: In this omnibus that I have they’ve been colored. So then having Laura (Allred)’s colors on the monthly and the way that that package came together is just astounding. You can see how, when it came out, it really did have an impact. People were so excited by it. It was something that was different.

I guess The Crow‘s black and white too. Most of your list is.

Cliff: Yeah, they’re mostly black and white.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription