The Comics That Made Them with Ram V

The comics you read and the comic experiences you have at different times in your life often form the building blocks of your relationship with the medium. Obviously what you’ll enjoy expands from there, but for readers, those earliest experiences can be enormously influential on you going forward. It’s the same for our favorite creators. Some of those foundational elements can define the interests or views of writers or artists in the future. This interview series is all about those, as I chat with creators about five of the biggest influences and inspirations from the time before (or while) they were working in comics.

This is The Comics That Made Them.

As I’ll get to in the first question to this interview, I knew before I even asked writer Ram V that he’d bring a unique flavor to this interview series. That’s why I was delighted he said yes, as I expected this to be an interesting variation on an interview series I greatly enjoy. It seemed certain he’d make unconventional picks, especially because his journey with comics was much different than the other folks I’ve talked to for this.

I just maybe didn’t expect this different.

So far, folks have exclusively selected comics or comics-adjacent things for their picks, because it’s in the name. But Ram threw out convention and selected the right things for him as a writer, not just a comic book writer. And sure, that includes comics, although even those choices weren’t exclusively traditional examples of the medium. But there was also a prose author and the entirety of the works of a single musical act. There are no explicit rules for this column that state you have to pick comics, and Ram took that and ran with it.

It made for a version of this chat that might have been even more interesting than usual, and one that took us everywhere from his history with the medium and the boxes creators live and are put in to how his engineering brain 9 affects him and even a major change that’s coming for the writer’s career. It’s a sprawling conversation about The Comics That Made Them, but really, it’s a look at how one of the best and brightest writers the medium has to offer became who he is. It’s a good one.

You can read it below. It’s been edited for length and clarity.

I told you over email that I thought you’d be an interesting fit for this exercise, and the reason for that ties into an anecdote I believe Paul Levitz once told me. I think it was Paul Levitz, at least. Apologies to Paul Levitz if I just made something up.

But the idea is that your favorite comic when you’re 13 will be your favorite comic forever, in the sense that it’s the one that defines you. That’s why you’re an interesting fit for this exercise. You weren’t even reading comics when you were 13. You had a gap between age 13 to 19 or 20. How do you feel like that gap shaped you? Do you feel like taking that break from comics, where it was a choice rather than because you burned out from it, do you think that shaped your relationship with the medium?

Ram V: Look, it wasn’t really a choice. My dad took all my comics and put them in trash bags and threw them away. So, it was an enforced choice in that way. He said, “You have to read proper books now,” and handed me a (John) Steinbeck book. That explains why I was an emo kid through most of my teenage years.

I think it shaped what I do because I don’t think about comics so dogmatically, in that I’m not trying to recreate a piece of my childhood. I’m just trying to tell good stories because I loved stories since long before I was a teenager. And it lets me think about comics in ways that I’m not too precious about.

My mind goes back to a conversation I’d had after working on my first DC short story. I was at dinner with Jamie Rich and Jorge Fornes, who collaborated with me on that story. Jamie had asked a bunch of other people around the table, “What do you think is most important to writing superhero comics?” A common answer was, “You have to be a fan first.” And I think I was the only person at the table to say, if anything, you should be the opposite of a fan. From a purely philosophical standpoint, you have to be willing to do things with these characters that a fan might not necessarily do, and you have to be willing to change things about the characters that you don’t necessarily think of as a fan.

So, I think when I took that break from comics, that meant there was no childhood or teenage nostalgia associated with it. It was pure. I came back to comics around the age of 19 or 20. Someone handed me the first volume of Sandman. It was this pure mental explosion that happened in my head where I thought, “Oh, these are all the possibilities.” And I think that approach, “These are all the possibilities,” continues to be a throughline in my work.

We’re going to get into five different things that impacted you, and most of the time when I talk to people for this, it’s them picking five comics. That is the parameters of this exercise, and while you picked three comics, you also picked a band and a prose author, albeit one who has a comic connection.

That’s one of the things that’s interesting about comics. I’m sure every medium is like this to some degree, where people who make video games, sometimes their biggest influence is other video games. Some people who make films, the biggest influence are other films. In comics, particularly superhero comics, something that happens a lot is that people who make comics often almost feel like they’re making comics about comics, or comics that are connected to comics. Do you think our vision, as in the wider world of comics, of what can be influential to creators is perhaps a bit navel gaze-y in that regard?

Ram: I think it goes deeper, right? Even within comics, there’s a need to compartmentalize and protect that which is familiar and comfortable to you. Superhero comics readers and writers who are influenced purely by superhero comics tend to write within that sphere. So then anything else that comes out that’s trying to be either raw and vulnerable and mundane and human is not interesting. Anything that’s trying to be intellectual or weird or strange becomes pretentious.

The same is true of the indie comics people, those who are doing slice of life comics or autobiography work, and then suddenly they’ve gone on to do superhero things and they get looked at with suspicion. And the same is true of the literary comics side of things. They get looked at with a suspicious eye. These are all things that happen in mediums because people like feeling comfortable and valuable where they are. But with time, if you’re truly someone who is purely interested in the artistic expression and the creative side of things, then you realize that these boundaries exist so someone can put a bunch of books together on a bookshelf in a bookstore.

They don’t exist for creative reasons.

Creators often get kind of put into a box, where it’s “if you’re an indie creator, you’re an indie creator,” and “if you’re a superhero creator, you’re a superhero creator” and that’s that. Occasionally, there’ll be a connected formed between those sides, like…did you ever read the Strange Tales anthology at Marvel did? 10

Ram: I did. I loved that.

I think it’s amazing. In it, you see people like Kate Beaton, Harvey Pekar, and a bunch of others who are famous for “indie comics.” And I always felt like Marvel readers and even Marvel itself to some degree were like, “I don’t know what to do with this.” I loved it. The thing is any lines that exist between comics are fundamentally imaginary.

There’s no reason you can’t cross those lines.

Ram: No, and sometimes as a creator, you start seeing all the lines, all the boxes, that other people start drawing around your work. It’s always funny to me. People go, “Ram, you’re a horror writer.” And I say, “Really? I am? Why do you say that?” They’re like, These Savage Shores, Blue in Green. Swamp Thing. But I’m like, yeah, but New Gods is not. Laila Starr isn’t. Rare Flavours…maybe. Black Mumba was not, or Grafity’s Wall.

But people who only read Laila Starr and Rare Flavours, they pick up my Detective Comics run and go, “What the hell is this?” I think people like to form boxes around things because that’s how we remember them. We compartmentalize everything, right? Paul Auster is my favorite literary author. Stephen King is my favorite horror writer. But you forget he did Shawshank Redemption, and you forget he did Green Mile.

I think boxes exist as a reader/marketing thing. They don’t necessarily exist as a creator.

That is true. I’ve talked to marketers about that sort of thing where they’re like, “We position it for this age group” or “We position it for this genre” because it makes it easier to sell. I think people like boxes more than creators, because it seems a lot of the joy you…you know, the royal you, get is from literally going outside the box in this situation.

Ram: Do you know the Velveeta story?

I mean, I guess, it depends on which Velveeta story.

I don’t know a lot of Velveeta stories, though.

Ram: Someone else told me this and so I don’t know the details but apparently originally Velveeta came up as a way of making organic glue. When they realized they couldn’t use it as organic glue they went, “Well, it’s edible. Why don’t we just sell it as a cheese substitute?” And it became Velveeta. Talk about marketing people going, “Well, it doesn’t fit into this box. How about this one? Okay, great. Let’s put it in that box and sell it.”

So, to me, boxes are marketing things, and the sooner creators and fans realize that that’s what those things are, the better and less dogmatic their view of things would be. At some point you have to stop thinking of yourself as a mover and shaker in this tiny little pond and start thinking of yourself as someone who just appreciates things that are good.

Good is the biggest box.

Sometimes I wonder how comic specific things like this are. They probably aren’t, but I think about the fact…I’ve had this conversation several times on the podcast recently where if somebody that makes comics starts making a different type of comic or something else entirely, they almost cease to exist. Matt Fraction is making Adventureman, so suddenly, people are like, “Where is Matt Fraction?” He’s making a comic, it’s just at Image, and it isn’t necessarily your exact vision of a superhero. And it’s funny how when you’re not in that box, people are like, “Where’d that person go?”

They’re invisible now.

Ram: And sometimes people use that to ratify their own feelings about authors as well. And you get all these judgments as to why people aren’t in the tiny little sphere that you’re looking at. Where that person is literally just around the corner, and you could just turn your head and look and go, “That’s what they’re doing.”

People are funny. I’ve talked before about looking at bigger data and finding funny things, and I look at social media as this giant pot of data. You start finding all kinds of funny things about how people react to stuff.

This gives us a good spot to talk about something related to what you’re saying before we get into your five picks. You are going to a different box. You are letting your DC exclusive lapse and you’re moving on from superhero work soon, including The New Gods, which will be wrapping with issue #12. What made you want to do that? Why did you let it lapse? Because I think a lot of people would be like, “You have so much momentum, Ram. You’re crushing it.” Why do you want to go in a different direction?

Ram: Because I’m crushing it in multiple boxes. (laughs)

But no, it’s partly out of necessity. I always find it funny when people go, “You’re a very productive author. You made all these comics.” And to that I say, yeah, but I’ve also done a film script, two pilots, and a video game at the same time. I adapted one of my own books to film. I wrote a video game. I wrote two animated pilots. And all of this was over the course of the past couple of years. Some of those things have come to fruition, to the point I’m going to need to invest time in them. I can’t sustainably do multiple issues of superhero comics that have to come out every month that have 15 other people involved in terms of production deadlines.

So, I thought it made more sense to wrap right at the end of my exclusive.

I had a conversation with DC, and they were kind enough to extend their offer. But I said, “listen, I think right now I’m in a space where I can do a limited number of things. When I have time, we work on them and when we have enough in the bag is when we solicit and announce.” I think that to me is a much more conducive way of working than the monthly cadence that I’ve been on for more than two years now. I did…what? Swamp Thing, then straight onto Detective, then straight onto New Gods, and I also did The Vigil and Resurrection Man as miniseries around that time. That’s not to say New Gods has ended. We have an invitation to do another arc. But perhaps its something we come back to, in time.

So, I made a lot of comics, and I also feel like it’s a good time to take a break creatively. I believe you have to reinvent yourself every 10 years as a writer. Otherwise, you run the risk of becoming stale and boring and just doing the same things you were doing when you started out. You have to come back to it fresh. That involves me spending time with my four-year-old sitting in my backyard staring at the sky.

I can certainly afford to do that, and I would like to.

I think one thing people forget is opportunity cost. If you do this, you can’t do that, at least to some degree. Sometimes people think of writers, especially comic writers, are capable of writing everything. Jeff Lemire is a good example. He does a lot. But everyone has limits. Every project you take on, there’s a cost on the other side, and that’s another project you can’t do. It seems like you’re just flipping the script on opportunity costs and focusing on something new to tap into a new energy.

Ram: Yeah. Also, there are lot of benefits, right? It’s purely mathematics at some point in time. I recently linked a YouTube thing on my socials where it was Paul Harding talking about writing his Pulitzer winning novel, and his advice was, “Take it slow.” And the reason he said that is because you forget that even during writing, it’s thinking time. If you think about your words, if you think about what you’re writing 10 times versus five, if you’re confident enough and not self-critical and nervous, it’s going to help the way you write.

I found that I missed working like that. I worked like that on Blue in Green. We were making two or three pages at a time. I would look at the art and then write the next few pages based on how the book was looking at that point in time. There was a cadence to it that was crazy. I wouldn’t want to do that forever. But I also don’t want the other side of it where you think, “Okay, I’m going to move on to the next script,” and you haven’t even seen the art from the previous issue come in yet. And that’s the cadence of monthly comics. And I feel like if you do that for long enough, it starts affecting the way you think about writing, and it’s not always a good thing to do.

So, what’s your first pick for this exercise?

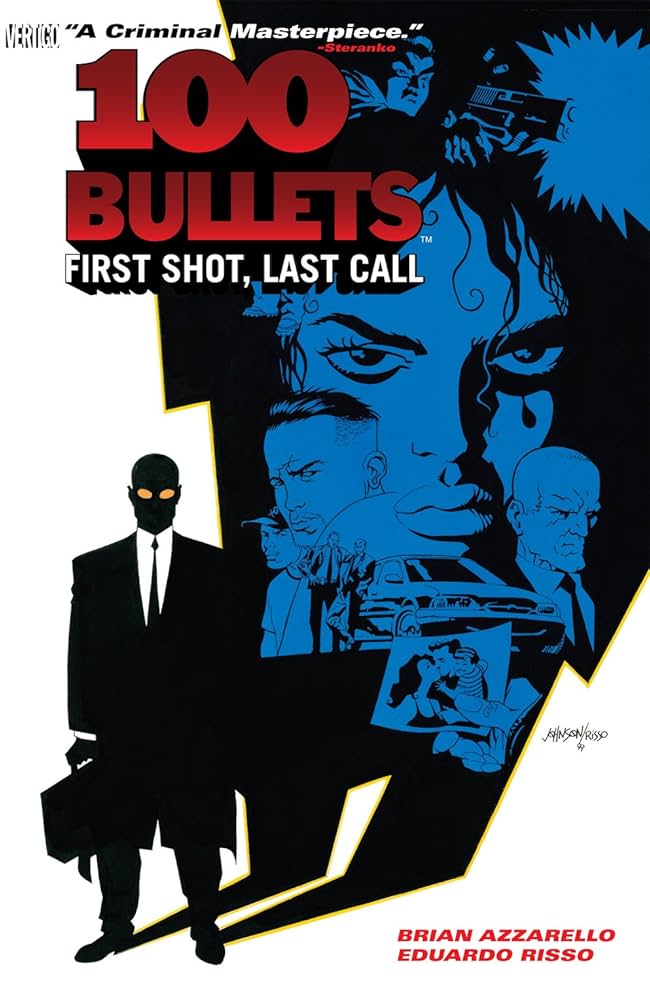

Ram: My first pick is going to be the book that I studied the most to learn how to write comics. It’s going to be 100 Bullets by Brian Azzarello, Eduardo Risso, and edited by Will Dennis, and this was at the now famed Vertigo lineup.

What made that one of your picks? And how did you study it?

Ram: I’ve mentioned this before when other people ask for advice, but I don’t know how many people follow it. Somewhere is a spreadsheet where I broke down pretty much every aspect of the entire 100 Bullets run into pure numbers. How many scenes in an issue, how many pages per issue, many pages per scene, how many panels per page, how many words per panel, how many total words on a page. I looked at every angle I could think of to come at the statistics of making a comic. And I looked at them purely as datasets and tried to make sense of, “Can I find cause and effect? Can I find patterns within this data that will tell me something other than me having to do six panels on a page?” And sometimes you go to somebody else and say, “no, you should do five panels on a page.”

So, instead of that prescriptive stuff, I was going, “Where did that come from? Why does that work?” It was exhausting and made the book a little bit unenjoyable to read because you were trying to count how many words there were in every panel. But thankfully I did a couple of readthroughs before I did that with the analysis side of things.

I spent so much time with that book. I’ve chatted with Brian a few times now, but I don’t think I’ve even told Brian that I studied it to this extent. Because he would have looked at me and thought, “Are you a mad person?”

That’s just how your brain works, right? It fits your engineering background. So, it just naturally ties into how you look at things and see the world.

Ram: It’s not the only way to look at it, because you have to have nebulousness. You have to have art. You have to have taste. You have to know when to take leaps of faith. But you get better at knowing them if you also understand how everything works, right? It’s one thing to take a leap of faith not knowing how to take a long jump. But if you knew how to take a long jump, then taking a leap of faith becomes much easier.

That’s a very big task to take on. Why 100 Bullets? Why was that the one you went down that path with?

Ram: To be honest, it was pure chance. It was around the time I was starting to consider, “How do I write a comic?” I had already finished reading all of Sandman by then, and I had been through a lot of the Vertigo stuff, Gaiman, Morrison, and Moore, at that point in time. And it just so happened that I had just started reading 100 Bullets. And I went, “I should really break this down and understand how it’s written.”

I think this was after I did my first self-published book, Black Mumba. This was somewhere around the time I was starting to write Grafity’s Wall. And so, I think to an extent it was just chance and timing. But it’s also a book that works very efficiently in a way that a lot of Gaiman, Moore, and Morrison’s work didn’t.

You can still read Sandman and go, “Here are tangents or these mini stories. I don’t know if they add anything greater to the plot, or here’s the thing that works over three issues.” But when 100 Bullets started, it worked as contained single issues that had beginning, middle. You had different ideas and characters in each issue, and they all worked. They were almost set to a metronome. At the risk of taking the joy out of it, they work perfectly.

And I wanted to understand, “Why does this work perfectly?”

That’s the amazing thing about that series, especially early on, is just how structurally perfect it is. In the early arcs where it’s just focused on a person being handed a case to solve their problems, it’s just such an exquisite structure for an arc. Is it the only structure? No. But I imagine understanding the rhythms and how that works and how that structure fits together…once you understand that you can be like, “How do I apply this to my own work and expand on it?” It’s not the one answer, but it could lead to more answers.

Ram: Yeah. And I think taking anything structural like that also gives you a lot of angles from which to come at it. Structure-wise, I’ll put it in architecture terms. I would find it much harder to study a Gaudí, 11, who made so many things purely by instinct. Some of his architectural things didn’t even have drawings. It’s much harder to study him than study how to make a skyrise with every drawing available to you. Every choice, every mathematical calculation is there on paper, right?

So, I felt like I could analyze 100 Bullets in a way where I could see or at least take notice of every choice that was made. Whether by intent or not, that was of lesser concern to me. I didn’t want to see how Brian Azzarello was writing comics.

I wanted to see how the act of reading comics worked for me.

I mentioned the word rhythms…when you’re looking at the panel breakdowns, like how many panels are on this page and that one, it helps you understand cadences. I know this is a silly thing to say, but I often don’t think people look at panels explicitly as time. The way you use layouts is manipulating time and manipulating reader rhythms, and that’s so crucial to how comics are told.

Ram: Yeah, it’s very interesting that you mentioned time. I could go for hours on the time and text relationship. How long it takes you to read a panel has to have some relationship with how long it takes for you to look at a panel as well. If one of those things are too low, you better be doing it for a good reason. If you have one word in a large/wide panel, that panel better have a lot of drama happening in the art, a lot of things to look at, and a lot of things to take in story-wise.

If you give the reader no time to read a panel and no time to look at a panel, again, that has a different effect, like a ticking clock. Someone says, “Boom,” and you show the hand on a clock ticking. That panel is going to be a thin one. It’s not going to be wide. It’s going to be because you want the reader to spend only that much time thinking about it. Otherwise, the impact of that moment is lost.

100 Bullets especially is full of these kinds of choices, including where you take camera angles from. There’s a shot of a character flicking ash from a cigarette into an ashtray, but the shot is taken from inside the ashtray, so you just get a tiny circle and the ash falling through. And that is such an ominous way of showing malicious intent that I cannot help but think that choice was made consciously for that effect. And so you start analyzing what kind of shots were taken, how many high angle shots an artist takes in a book, and when they’re taken.

I was talking to Nick Dragotta in San Diego, and I’ve talked about this with Evan Cagle as well, about how that was the first time I noted an artist expressing scale. If you look at Dragotta’s work in East of West, that’s another artist who can express scale. And there are very specific choices in shot angles and depth and how you place the characters that are made to insinuate scale. Not every artist gets it.

These kinds of choices are fascinating to study because then when you’re scripting something, you’re scripting it with intent and not just going, “I’m writing a scene, the artist will figure that out.” 100 Bullets is very important to me for that reason. There was a lot of analysis and a lot of hours sitting there looking at spreadsheets.

Not to discount Azzarello, but that’s what you get when you have Eduardo Risso on a book. He has such a singular perspective when it comes to framing shots and mood and atmosphere. Even though it’s hard to express that in engineering terms, that stuff is so crucial.

Ram: No, it absolutely is. I think it was less for me about what Eduardo did and what Brian did and more for me about analyzing the comic as it existed. I was less concerned with attributing who did what to which creator because I am fairly sure, as with most other comics where you have incredibly talented, mercurial creators, there must have been instances where Eduardo just went, “I see this in the script. I’m just going to do this.” Who knows? But my exercise is not one in attributing who did what to which choice. I just want to learn how to make good comics. I don’t want to learn the writer’s or the artist’s part.

I just want to learn good comics.

What’s your second pick?

Ram: We’ll go prose this time. It’s Paul Auster, or his general body of work. I came to Paul Auster much later as I was starting my creative writing course. It was one of my tutors who recommended Auster’s work to me because he saw my genre leanings, but this was also a literary writing course. You’re not going to write Game of Thrones with dragons in it, you’re going to have to write literary fiction, which is basically to say fiction that is concerned with good prose and structure. It can still have dragons in it, although I know Jonathan Myerson would disagree.

I came across Paul Auster then, and I think that was the first time I had an inkling about what kind of stories I want to do. You can certainly see it in my creator-owned work. Blue in Green and The One Hand and The Six Fingers certainly fall into that category of Paul Auster-ian stories, if you will. He was just a unique author with a way of looking at story and structure that influenced me at that pivotal time.

Is there anything specific from his work that resonated with you going forward?

Ram: I think it was the first time I had come across this author who was considered one of the stars of postmodernist writing, someone who would write a novel that was aware that it was a novel, that was aware of the history that it came from and its conventions. So, if you take City of Glass, for example, that is a novel that is aware that it was born from the late 1980s American pulp detective noir subgenre. But I don’t think they’re just detective stories. They’re stories about an author being a detective about his own identity. And all three of the stories carry that theme.

They’re in some way about writing and finding yourself. Which is funny because the example I will mention, it’s the first time this struck me, is in City of Glass, the protagonist is an author who dreamed of being a poet but ended up writing these schlocky detective stories. And the character that he’s most known for is this detective with a cheesy name like Sam Spade. And then the story begins with him actually in the loo when the telephone starts ringing. So, he has to rush out and as he picks it up, he hears a voice on the other line and it says, “Hello, can I talk to Paul Auster?”

It was at that point that I was just thought, “What are you doing here?” It’s easy to dismiss that as just metafiction. We’ve seen that before. But what Auster does with these kinds of metafictional elements is more than just a gimmick. He’s using it to question the reader’s and writer’s relationship with the story, the characters, and how the sense of authorial identity exists within the story. And you see this happening throughout the books.

There’s also another reference that I think The One Hand and The Six Fingers enjoyers will enjoy. There’s a part in that where they talk about a father who performs an experiment on his own kid. When the child is born, he locks him away in a room and gives him no human contact to see if the child will come up with a way of speaking a language of God, if you will. And there’s a reference to the very same language of God in The One Hand and The Six Fingers, which tells you how much I’m thinking about Auster whenever I’m writing a story.

Do you carry specific things from Auster with you going forward beyond references like that, or is it more about what it made you feel and how it made you want to tell stories when it comes to Auster as an “influence,” if you will?

Ram: There are specific things as well. You know the coin trick that magicians perform where they palm the coin and then it looks like it’s gone? Everyone knows that one, right? So now when you look at that trick, you go, yeah, I know that one. It’s when you see a trick that you can’t explain that you’re suddenly saying, “Wait, what did you do?”

For me, most of Auster’s work was like that originally. His prose is like being on a locomotive. You’ll think, “I must have spent five minutes reading this.” And then you look at the time and 15 minutes have gone by, and you’ve read through the first three chapters because it has that propulsive nature to it. It just keeps pushing you into the next line. And that comes from how you choose your words and how long your sentences are and what words go where and how it feels to think of those words in your head. You must have such great control to make your writing do that.

And sure, you could dismiss it as an accident, except he does it in every single book.

You mentioned in an interview with The Comics Journal that you weren’t interested in becoming a comic book writer. You were interested in becoming a writer of anything. I mentioned this earlier to some degree, but I think sometimes when comic fans think of comic writers, they’re just like, you know…Grant Morrison is obviously an influence. Alan Moore is obviously an influence. “No one’s like, obviously Paul Auster is an influence.” Well, unless they’ve read a lot of Paul Auster.

But we talked about the boxes earlier. Boxes don’t have to exist. And it seems like with someone like Paul Auster, he’s a good example of the fact that an influence can come from anywhere because you never intended to be one type of writer.

Ram: To be fair, you could also read a lot of comic book writing and instead of going, Morrison, obviously an influence, you could also go, Beat Generation writing, obviously an influence. You could look at Alan Moore inspired work and you can see the Thomas Pynchon in there. It’s good to have influences from outside your own medium, and there are a few reasons to say that.

It’s the iceberg principle, right? When your favorite authors wrote something, their influences were 5, 10, 15 times whatever you see on that page. If you’re just reading that and trying to make something else, and you don’t have all the other influences they had…music, novels, film and TV, whatever it is, you’re always going to be making a smaller tip of an iceberg than they did and it will never surpass or match up to what they were doing.

That’s why I also feel this sort of doomed sense of, “We will never have our Golden Age back” goes hand in hand with the same doomed sense of, “Oh yeah, I only read Morrison or Moore before I start making comics.” I think those two things go hand in hand. You really want to have another Golden Age, you have to read prose, watch film, play music, break your leg on a skiing trip in the middle of nowhere and figure out what that was like.

Was that a personal experience?

Ram: Not a skiing trip, but I have been lost in the woods with a broken leg. (laughs)

Not fun.

There was a book announced last week from Nick Dragotta and David Brothers who did these three stories together that are going to be released at Image as Good Devils: Don’t Play Fair with Evil. And in the press release, David talked about how Gil Scott-Heron was a reference, and he was a spoken word musician and poet. Some people might see something like that and think, “What the heck?” But inspiration can come from anywhere. There’s no reason to put that in a box too.

Ram: If you are an avid comic reader, tell me what excites you more: Another person who says, “I’m trying to do Morrison,” or someone who goes, “I’m going to take spoken word music and turn that into a comic book.” To me, to me as a reader, that’s more exciting. I don’t want to see another version of Morrison. I’ve already seen that. I’ve already stood at the tip of that iceberg.

You’ve read David Mazzucchelli’s adaptation of City of Glass. How was it seeing a story you loved through the prism of how a cartoonist interpreted it? Was that strange to see his vision of a story you knew very well?

Ram: No, it wasn’t. If anything, I find it very affirming of my own taste. (laughs)

I find it very affirming to look at these kinds of connections that I had because I had read Auster separately and I knew of Mazzucchelli’s work separately. And I only came to City of Glass, the graphic novel adaptation, after those things.

To me, it was this combination of these two things that made sense because they’re both incredible and lovely. It’s funny, the number of times I have found stuff like that, to the point I joke that all cool people are secretly people who want to make comics. Did you know Italo Calvino had a book he wrote in the form of comic scripts? This was before he knew he was writing comic strips, but they were essentially still images and dialogue, but it wasn’t stage direction. He was describing images. So, really, he was just writing a comic book script.

I met author and illustrator George Butler during his talk called Drawing from the Truth. He was a war journalist who had traveled to Syria to draw and illustrate scenes of everyday people trying to get on with their lives under the cloud of this war. He was on stage and someone from the media was asking him, “What’s your next project? What are you going to do?”

And he goes, “Well, for 12 years, I’ve been trying to make a comic that no one will publish. I just want to find someone who will publish my comic.” I found that immensely amusing.

Have you ever read any David Mitchell? 12

Ram: Yeah, I’ve read David Mitchell.

I love David Mitchell’s work and I’m 100% convinced that dude wants to write comics or at least is influenced by them.

Ram: Yeah, it would lend itself very well to just being a comic book.

Some of his work would be trickier. He did this one book, Black Swan Green, that’s very intimate and almost feels more like a play. But there’s some stuff where I read it and I’m just like, “Man, this guy really wants to make comics.”

Ram: Yeah, Ghostwritten, as well. I think that was my favorite. I think it was a collection of short stories, but he’s just a phenomenal writer and very comics adjacent.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

Ram was a chemical engineer at an earlier point in his life.↩

A series that, I must note, I did a retrospective on for SKTCHD.↩

Antoni Gaudí, the Spanish architect mostly famous for a whole lot of buildings in Barcelona, and perhaps most prominently the still-unfinished church Basílica de la Sagrada Família.↩

A novelist most famous for his work on books like Cloud Atlas and The Bone Clocks, the latter of which is a great example of what I talk about here.↩

Ram was a chemical engineer at an earlier point in his life.↩

A series that, I must note, I did a retrospective on for SKTCHD.↩

Antoni Gaudí, the Spanish architect mostly famous for a whole lot of buildings in Barcelona, and perhaps most prominently the still-unfinished church Basílica de la Sagrada Família.↩

A novelist most famous for his work on books like Cloud Atlas and The Bone Clocks, the latter of which is a great example of what I talk about here.↩

Ram was a chemical engineer at an earlier point in his life.↩

A series that, I must note, I did a retrospective on for SKTCHD.↩

Antoni Gaudí, the Spanish architect mostly famous for a whole lot of buildings in Barcelona, and perhaps most prominently the still-unfinished church Basílica de la Sagrada Família.↩

A novelist most famous for his work on books like Cloud Atlas and The Bone Clocks, the latter of which is a great example of what I talk about here.↩