Eric Stephenson on the World of “They’re Not Like Us” and Future of “Nowhere Men”

We explore two of Image's most exciting titles with their writer

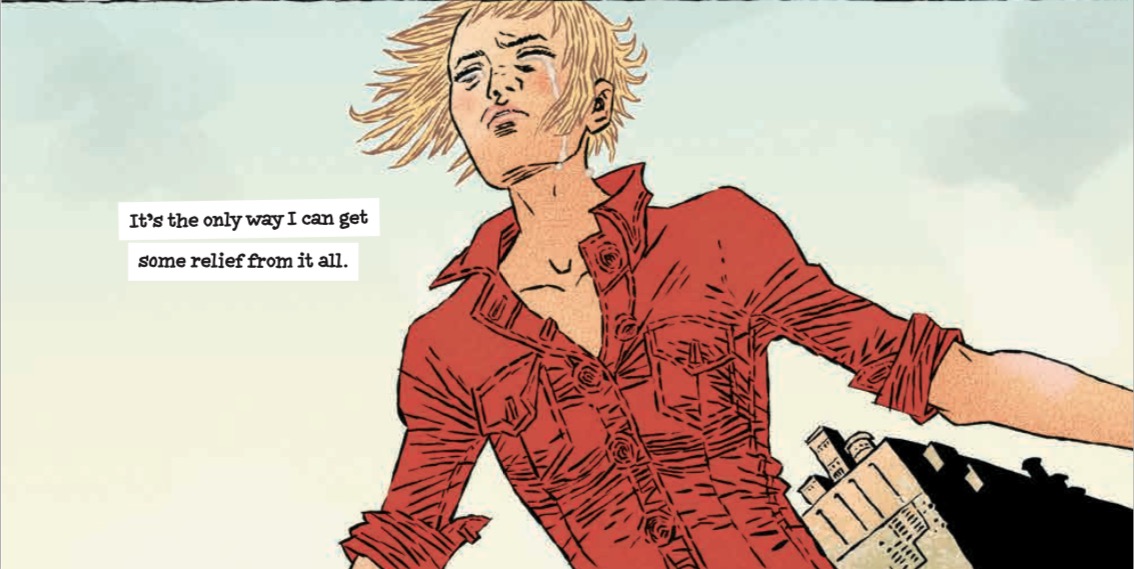

While many only know him as “that guy who runs Image”, the secret about Image Publisher Eric Stephenson is that he might be as good at writing comics as he is at running everyone’s favorite comic company. His work on “Nowhere Men” earned him an Eisner nomination in 2014, and he followed that up with similarly incredible work in “They’re Not Like Us”, a very real world look at the lives of super powered young people. It’s a tremendous book, and one that provides a very dark, very real feeling look at what it’d be like to be young, troubled and gifted.

The first arc of that just wrapped with a trade of the first volume arriving on July 8th, and I spoke with Stephenson about his work on the book, whether he sees himself in any of the characters, what drove him to create it, and much more. It’s a deep dive into the book, followed up with some talk about the pending return of “Nowhere Men” with the original team entirely intact. Take a read, and when you get a chance, check out his books. You’ll be really happy you did.

Nowhere Men seemed like an obvious book in terms of relating to your own personal interests. There’s the Beatles angle, the science, the captains of industry and other angles that seem directly of interest to you. They’re Not Like Us is perhaps a bit less obvious, with its focus on the broken youth of today. What made this a story you wanted to tell, and perhaps something you are personally connected to?

ES: Well, I started developing They’re Not Like Us a while ago, at a point when it looked like Nowhere Men wasn’t actually going to happen. I’d spent a lot of time – several years at that point – thinking about this world that grew out of a greater focus on scientific achievement and how different everything would be as a result, but I had kind of reached a dead end in terms of finding a suitable artist for the project. For the sake of my sanity, I needed to put work on that to the side for a bit and try to do something else, and I decided I wanted to do something a little less complex. Then I got mugged in Downtown Oakland by a group of kids who seemed more interested in just giving someone a hard time than anything else, and that got me thinking more about how things actually are as opposed to how things could be. For a lot of young people, there’s a growing level of dissatisfaction with the world, a feeling that there isn’t much waiting for them as they become adults — that they don’t have many options in life. With that in mind, I started wondering how kids with that kind of frustrated outlook might act if they were born with abilities that made them stand out from everyone else. Would they use those abilities for the benefit of others, or would they use them to benefit themselves? Everyone is born with unique talents, and generally speaking, everyone uses those talents to get ahead in life, but if you think there isn’t any getting ahead in life, what happens then?

Now, I know it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison, but there’s a part of me that read the first six issues and wondered how much of you – maybe one third? – is in The Voice. His aspirational record collection, his rules of appearing dapper at all times, and his opinions on the Internet are, while obviously narrative driven, things that run in parallel to your interests seemingly. He even sort of looks like you in the way Simon Gane draws him. Was that intended in a way, or am I just reading too much into the character?

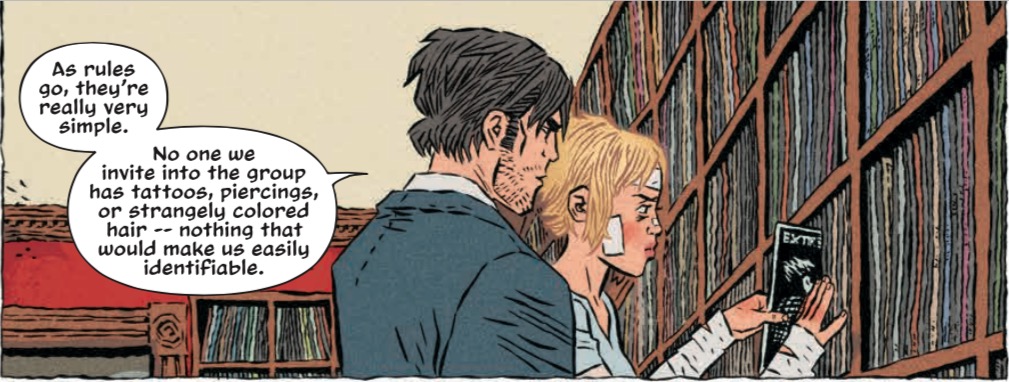

ES: Maybe a little. Stuff like The Voice’s aversion to cell phones and the Internet, though, are really just the result of looking at what steps someone might take in an effort to become more or less invisible in a society that is increasingly geared toward tracking our every move. The Voice’s m.o. is to more or less to hide in plain sight, but he reasons you can’t do that if you have a cell phone number or an email address. Similarly, he doesn’t want any of the kids in the group to have tattoos or piercings or anything that makes them instantly recognizable, so yeah, all of that is pretty much there to serve the narrative. The clothes are part of that, too. He figures the more “respectable” he looks, the less likely he’ll be under suspicion for any criminal act he’s associated with, which is just a reflection of how things tend to work in real life. A lot of people are rewarded just for looking the part, whereas even more people are unfairly hassled just because they look different. Beyond that, everything else is just an extension of The Voice’s acquisitive nature and his need to impress the kids he’s bringing into the fold. He’s trying to dazzle them with this private world he’s created.

Many have made the direct correlation from They’re Not Like Us to the X-Men, and while the parallels are there, it’s obviously its own beast. I’m curious, though: is that a comparison you welcome?

ES: To a certain degree, but really it’s only there because when I was first writing notes for the book, I realized there was a kind of parallel between Professor X and Fagin from Oliver Twist. Professor X was training young mutants to be heroes; Fagin was training young orphans to be thieves. They’re both mentor figures, though, and they’re both putting their charges in danger. That aside, the X-Men, to me, has always been about building a bridge between mutants and humans, finding some common ground, whereas They’re Not Like Us is more Us vs. Them. To The Voice, regular people are like zombies, and everyone with powers is trying to survive being dragged down by them. To bring it a little closer to home, I think The Voice would probably see himself as having more in common with Rick from The Walking Dead than Professor X or even Magneto. He’s a deeply flawed individual who thinks he’s doing what’s necessary to keep himself and those around him safe.

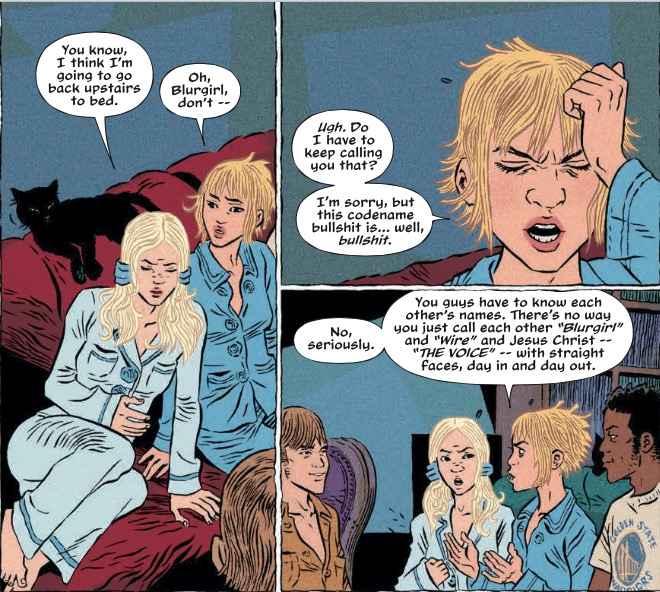

Speaking of that, one of my favorite bits was in issue #4 when Syd had a meltdown because of everyone in her new community using code names. Is that your own commentary on the rather ludicrous nature of one of superhero comics’ central tenets, or was it more a character beat of Syd dealing with the absurdity of her new life? Or a bit of both, even?

Speaking of that, one of my favorite bits was in issue #4 when Syd had a meltdown because of everyone in her new community using code names. Is that your own commentary on the rather ludicrous nature of one of superhero comics’ central tenets, or was it more a character beat of Syd dealing with the absurdity of her new life? Or a bit of both, even?

ES: Both, really. There are some great superhero codenames, but there are ridiculous ones, too. I mean, I love the Fantastic Four to death, but I’ve always thought Mr. Fantastic was an incredibly silly name, especially given that it doesn’t describe Reed Richards’ abilities in any way. I don’t think most people’s inclination would be to adopt a codename just because they have superpowers, and yeah, Syd just finds the whole concept annoying and weird.

If The Voice is more like Rick Grimes in how he views the world and how he leads, then what is Syd’s perspective? Or is figuring that out a big part of her story going forward?

ES: Yeah, that’s definitely something we’ll be learning about Syd as we push forward with the next arc. As of now, she isn’t really sure who she is or how she fits into things. She’s 21-years-old, she’s been in and out of hospitals her whole life and hasn’t really had much chance to interact with the world, so she has a lot to figure out. As notes in issue three, she’s never really had any kind of romantic relationships before. Things that are commonplace to most people her age are completely new, which is both exciting and frustrating for her. She has a lot to learn, basically, about herself and the world around her, and the next arc is very much about who she is going to become.

This book has something you don’t see out of a lot of comics, and that’s a feistiness that almost borders on being mean-spirited and callous. There’s a level of justice to what’s being meted out, but as Syd notes, the cast of characters tends to enjoy it perhaps more than they should. Is that something you were going for? Do you find that to be natural offshoot of young people who have lived lives like these characters did?

ES: I don’t know that it’s necessarily just young people, but I think mean-spiritedness has kind of become a hallmark of the modern world. There’s a lot of negativity out there, and a lot of disregard for others’ feelings, what other people are going through. People can point fingers at young people or at social media or whatever, but you know, it’s everywhere, from politics to the media to general public discourse. It’s not enough for someone to be right about something, they also have to humiliate the person perceived to be in the wrong, and despite the fact everyone has different opinions based on his or her personal experiences, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of sympathy or tolerance for that. If you disagree with someone, there’s no agreeing to disagree, they immediately become the object of scorn.

I think it’s interesting that you mention that there is both a growing dissatisfaction with the world in young people and that the world itself is just a lot meaner than it was in the past. Those two ideas likely have a symbiotic relationship of sorts, and not to bring us back to the X-Men again, but I do think it’s fascinating to think of some of the more notable comic characters and whether they could have come from an era like this one. I tend to think not. Do you think the heroic ideal has become passé in today’s fiction, if only as a reflection of the time we live in?

I think it’s interesting that you mention that there is both a growing dissatisfaction with the world in young people and that the world itself is just a lot meaner than it was in the past. Those two ideas likely have a symbiotic relationship of sorts, and not to bring us back to the X-Men again, but I do think it’s fascinating to think of some of the more notable comic characters and whether they could have come from an era like this one. I tend to think not. Do you think the heroic ideal has become passé in today’s fiction, if only as a reflection of the time we live in?

ES: I don’t think the heroic ideal is necessarily passé, no. I mean, it’s not like this is the worst time in history, and it’s not like there aren’t people doing good things for one another. Yeah, there are a lot of shitty aspects to modern life, but at the same time, I don’t know that any other point in history realistically fares any better. You look at a show like Mad Men and sure, everyone dressed great, and that mid-century modern furniture in the offices looked amazing, but it was just as tumultuous a time as we’re going through now. Women were treated like shit, anyone who wasn’t white was treated like shit, children were treated like shit, we were in costly war with Vietnam. It’s easy to glamorous other periods in time and think they were better, but we’ve always struggled. Superheroes weren’t created at a point when everything was rosy and everybody was great: Superman, Bat Man, Captain America — they were a direct reaction to a world that was kind of going to shit. Then, when World War II was over and things had calmed down a bit — if you can call the Cold War and Korea calming down — horror took hold of everyone’s imagination, whether it was at the movies or in comics or whatever. That’s the thing with fiction, it isn’t always a reflection of the times we live in, sometimes it’s a reaction to those times.

There’s a lot to criticize these days, but ultimately, there are many, many people still striving to make the world a better place. That’s not what we’re exploring in They’re Not Like Us, but that’s definitely the mindset of the characters in Nowhere Men. When that book comes back and we get to know Dade Ellis a little bit better, we’re going to see that regardless of whatever has happened to World Corp over the years, he is still very committed to the principals on which that company was founded. With They’re Not Like Us, though, yeah, I’m looking at where we are now and how someone with a kind of jaundiced view of things might behave, and kind of more to the point, what it would take to change that view. Syd clearly does not share The Voice’s views, so where does that take her now that she has a greater understanding of her abilities? And how does she influence the other kids?

In some ways, the cast feels like a reaction to much of modern society, from its obsession with sharing everything with everyone to mental illness being responded to with medicine and little listening. Not that you are a proponent of public beatings of people, but is part of this book you wishing for more action from the young people of the world?

ES: You know, I’m not a terribly strong proponent of public anything, but beyond that, I think it’s more a case of wishing everyone could just learn to embrace what makes him or her unique without the need to see everyone else as different. Like I said a bit ago, we’re all special in different ways, but at the end of the day, we’re still just people. Blocking things out in “us” and “them” terms isn’t the most healthy way to deal with problems — it doesn’t actually solve anything, ever — and that’s something we’ll be getting into with the second arc.

With Simon Gane, Jordie Bellaire and Fonografiks onboard, you have a leg up on damn near every book on the stands, but even for them, they’re putting out peak work. What made each of them such a great fit for the book, and does having such a uniquely talented trio of collaborators allow you to do things you might not be able to otherwise with the story?

ES: Well, with Jordie and Fonografiks, it was kind of a case of working with them on Nowhere Men and realizing what a huge impact they had on that series. Nate Bellegarde is a fantastic artist, obviously, but Nowhere Men couldn’t have been what it was without Jordie’s and Fonografiks’ involvement. They took it to another level. I was just telling Jorbs the other day that I don’t want anyone else to color my projects, ever, and the same goes for Fonografiks. They are the best. The end.

Simon was recommended to me by Declan Shalvey, and when I see him in England this September, I’m going to need to shower him with gifts, because Simon was such an inspired choice for They’re Not Like Us. His attention to detail is second to none and he has such a way of bringing the characters to life that it’s hard to imagine anyone else drawing them. He’s also very deadline-conscious and just amazingly productive, so it’s been a real joy to work with him. Hopefully, we get to keep at it for a long time.

One of the things I think is most impressive about Simon is his ability to layer the book with so much detail – like Wire wearing a Golden State Warriors shirt as pajamas, for example – that it really adds to the realism of the story and gives it more weight. Is that something you specifically aimed for when thinking of artists for this project?

ES: That and the ability to get into really fine detail where the locations are concerned. One of the great things about Simon is he loves drawing architecture, and I think that is immediately apparent in some of his depictions of San Francisco, and of The Voice’s house, both inside and out. He has a keen eye for what people wear, too, which was something that was absolutely essential for this, and will become more so as the series progresses.

One of my favorite parts of the book is how every part of the book is story. You did that with Nowhere Men but this is a different level, using the cover as the first page and credits at the same time. Why did that become something you wanted to do? Was it just you looking to push the form and maximize storytelling space?

ES: I definitely wanted to do that, but also, I’m just super-appreciative of strong design. I love packaging. I just came across an ad for some chocolate from Belgium recently that is just fantastic, and my first thought was, “Man, I want that box!” before I ever even considered what the chocolate might be like. I do that all the time. So with both Nowhere Men and They’re Not Like Us, I was looking at different things and thinking about how this or that type of design might be applied to comics. One particular inspiration was the sleeves for 7” singles, which are these really compact little works of art — you’ve got your image on the front and then all the info on the back, very economical design. And of course, Fonografiks does such great work, it’s easy to pass on something I like and ask, “How can we apply this to what we’re doing here?”

ES: I definitely wanted to do that, but also, I’m just super-appreciative of strong design. I love packaging. I just came across an ad for some chocolate from Belgium recently that is just fantastic, and my first thought was, “Man, I want that box!” before I ever even considered what the chocolate might be like. I do that all the time. So with both Nowhere Men and They’re Not Like Us, I was looking at different things and thinking about how this or that type of design might be applied to comics. One particular inspiration was the sleeves for 7” singles, which are these really compact little works of art — you’ve got your image on the front and then all the info on the back, very economical design. And of course, Fonografiks does such great work, it’s easy to pass on something I like and ask, “How can we apply this to what we’re doing here?”

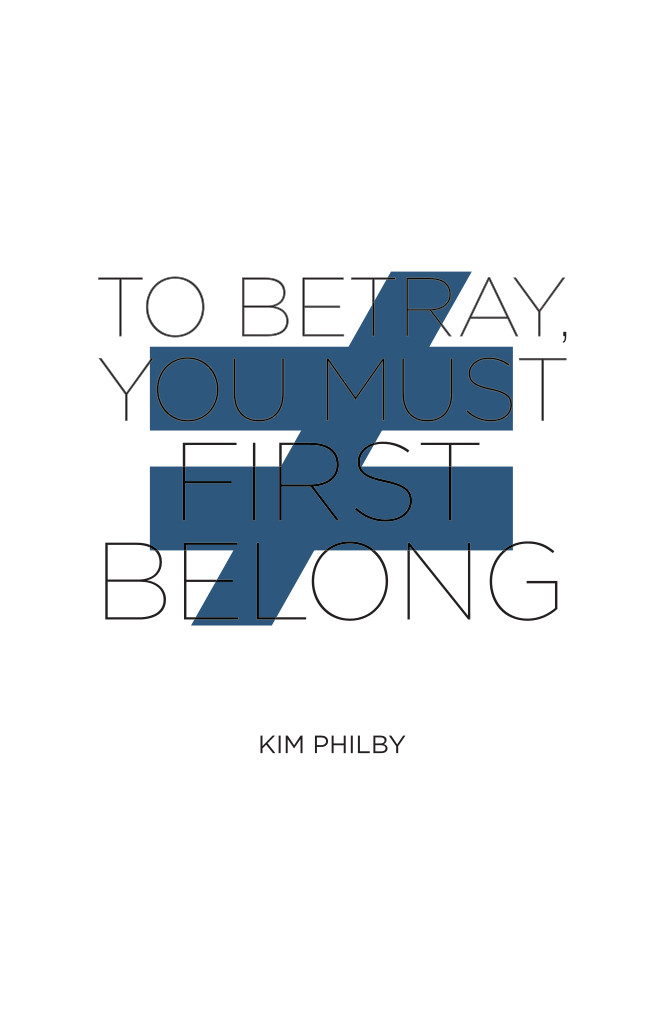

Another element that I think adds a lot of value is the quotes at the end of each issue that tie the whole thing together. Each quote, which are all from musicians save for one from noted spy Kim Philby, are great thematic umbrellas for each issue. Why did you decide to include those, and will those carry on into the collected editions?

ES: They’re part of the story, so yes, those are going to be reprinted in the trade. Each issue of They’re Not Like Us from front cover to back cover is part of the story, so leaving any of it out would be like giving people an abridged version of things. They started out as inspirational quotes as I was writing the scripts, but I’ve always loved albums that had interesting quotes in the sleeve notes – Manic Street Preachers were a big influence there – so I thought it would be a nice addition.

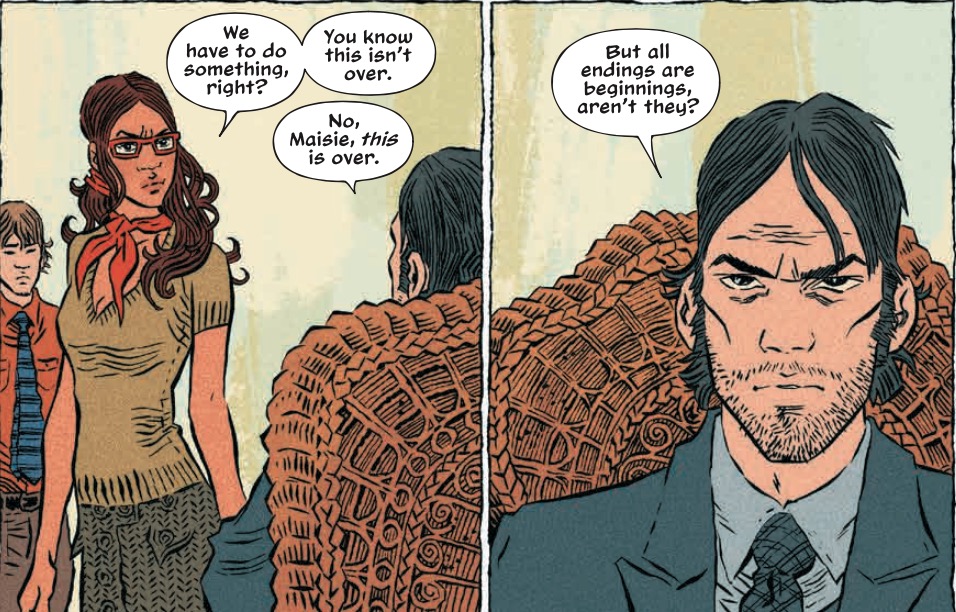

“But all endings are beginnings, aren’t they?” That’s how The Voice ends the first arc, with Syd/Tabitha on the way out and a number of others going with her, and it feels like just as the story started, it spun in a different direction. It could go a lot of ways from here, but I’m not going to ask what’s next. What I’m curious about is how finite of a vision you have for this series? Do you have a defined length you’re aiming for, or do you have an ending point that can be a new beginning depending on the success of the book?

ES: Much as Matthew Weiner was doing with Mad Men, where he viewed the end of every season as a potential ending for the series, especially early on, I kind of look at the end of each arc as a possible stopping point. I do have a finite vision for the series, it’s not all meant to go on forever, but there are different points it can stop ahead of where I’d ultimately like to go and still be satisfying for the reader. Hopefully. The aim is to do 36 issues — six trades — but we’ll see.

In August’s solicits, a new printing of Nowhere Men Volume One was featured, with word coming that it is prelude to the return of the series in the fall. Why is it time for that book to come back, and will its return impact They’re Not Like You in any way?

ES: Not really. They’re two different projects, and as far as the scripts go, I’m ahead on both of them. Simon is a machine in terms of generating pages, and since there’s a break between issues six and seven of They’re Not Like Us while we get the trade out, it’s looking like we’ll probably be finished with over half the second arc by the time we return in August. And Nowhere Men won’t be back until around the end of the year, so They’re Not Like Us will actually be heading towards its second break around that time, so there’s not a lot of actual overlap.

Why is it time for Nowhere Men to come back? Well, because it can, mainly. I would have liked to have it out sooner, obviously, but there have been a lot of complications outside my control. I get a lot of email about the book — people really seem to want it — so now that we’re nearing a place where we can come back and actually get issues out on a monthly basis, we’re going to see how it goes. The second arc kind of completes the story that started in volume one, but it’s really dependent on how well the new issues do whether or not we’ll continue on past that point. It’s been gone a long time, and I’m not delusional or anything – people hate that kind of shit and they may not be wiling to give us a second chance.

It seems that you approach your writing with trades or arcs in mind, with each arc close acting as potential stopping points as you said. Would you say that’s fair? What’s your process like for writing They’re Not Like Us?

ES: That’s a good assessment, yeah, especially with something like They’re Not Like Us. With Nowhere Men, it was a little different, but that was more circumstantial, really. I mean, the first trade does not wrap things up, it’s clearly the first part of a larger story. But again, that’s it’s own thing.

With They’re Not Like Us, my process is basically notes, notes, notes — most of which are entered into my iPhone at the oddest of times — and then sifting through that to figure out what actually fits into the overall framework of the story. I don’t know how other writers do it, but pretty frequently, I’ll write down lots of dialogue — whole conversations or maybe just lines — that sometimes doesn’t get used because there’s just no place for it. Or I’ll come up with an idea for a character and then something happens to make that irrelevant. But I make sure to get the ideas down as they hit me, because a big part of how I work is to just allow myself to be open to things, whether it’s something I observe, something I hear, a place I’m visiting, whatever. Since the book takes place in the Bay Area, I tend to take photos of interesting looking houses, because I’ll find myself wondering how that might fit into the kids’ world and things like that.

They’re Not Like Us Vol. 1: Black Holes for the Young arrives in comic shops, digitally and beyond July 8th for just $9.99. Keep an eye out for it.

All art from “They’re Not Like Us” created by Simon Gane, Jordie Bellaire and Fonografiks.