“This Gives Us an Outlet”: Members of the Minneapolis Comic Community on What It’s Like to Create During a Crisis

It might seem like an unusual comparison, but for some comic creators who reside in Minneapolis, Minnesota, living through Operation Metro Surge — the effort by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Protection (or CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (or ICE) that has been publicly described as an immigration enforcement push but has largely been an occupation of the city that has terrorized locals and resulted in the killings of two residents in Renee Good and Alex Pretti — has reminded them of the pandemic, or at least aspects of it.

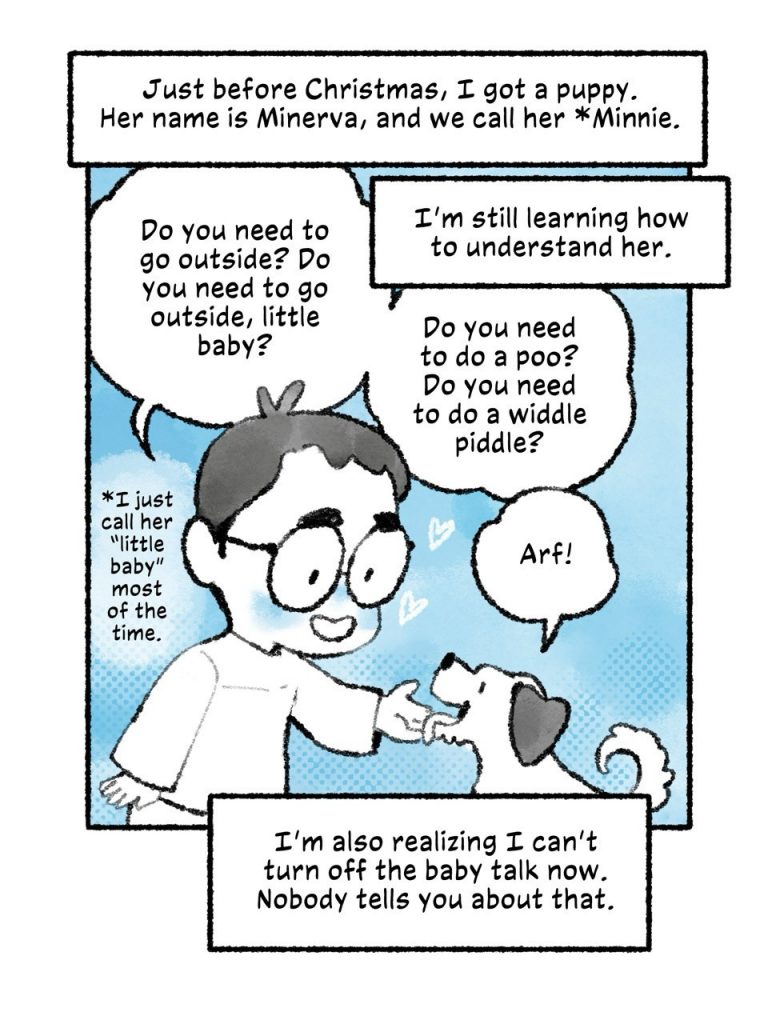

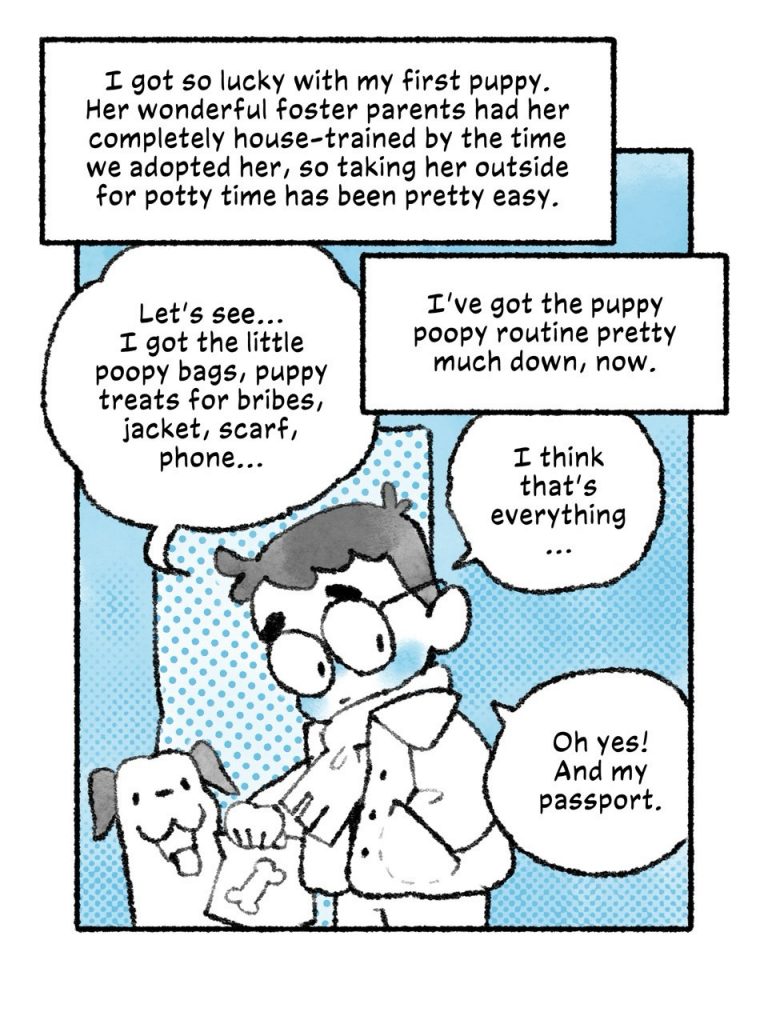

“I feel like I’m sheltering in place again,” cartoonist Trung Le Nguyen said. “I don’t really feel like I can safely be in public as a person of color, truly.”

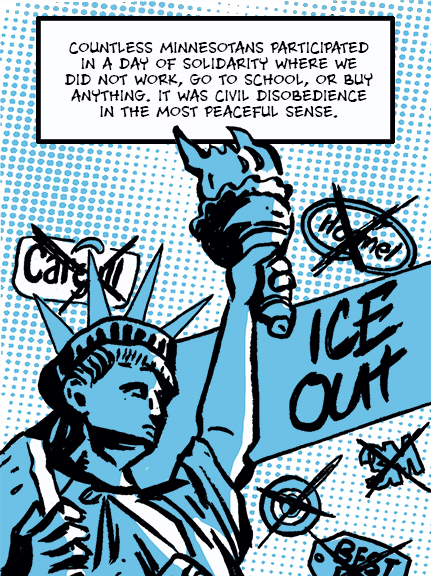

While everyone is “hanging in there,” as Nguyen put it, 1 it’s still been an unprecedented time that’s completely changed what it’s like to live in the area. Incredibly, though, the comics community has become a face of the city’s resistance in recent weeks. The image of 70-year-old retailer Greg Ketter of DreamHaven Books 2 making his way through clouds of tear gas and his passionate interview that same day quickly became focal points for anyone looking for a way to better understand what ordinary people were experiencing in Minneapolis as the presence of ICE overwhelmed the city.

But it makes sense that the city’s comics community would be at the heart of this. While it isn’t bandied about as a comic hotspot as often as others like New York or Portland, Minneapolis is an incredible comics city, with talents like Nguyen, Zander Cannon, K. Woodman-Maynard, John Bivens, and an array of others calling the area home. They’ve all become a part of this story, if only because it’s so inescapable, as ICE’s presence has existed as a nightmarish constant while creators go about their days — at least to the degree they can, really.

“Our lives have been completely turned upside down,” cartoonist Jason Walz shared.

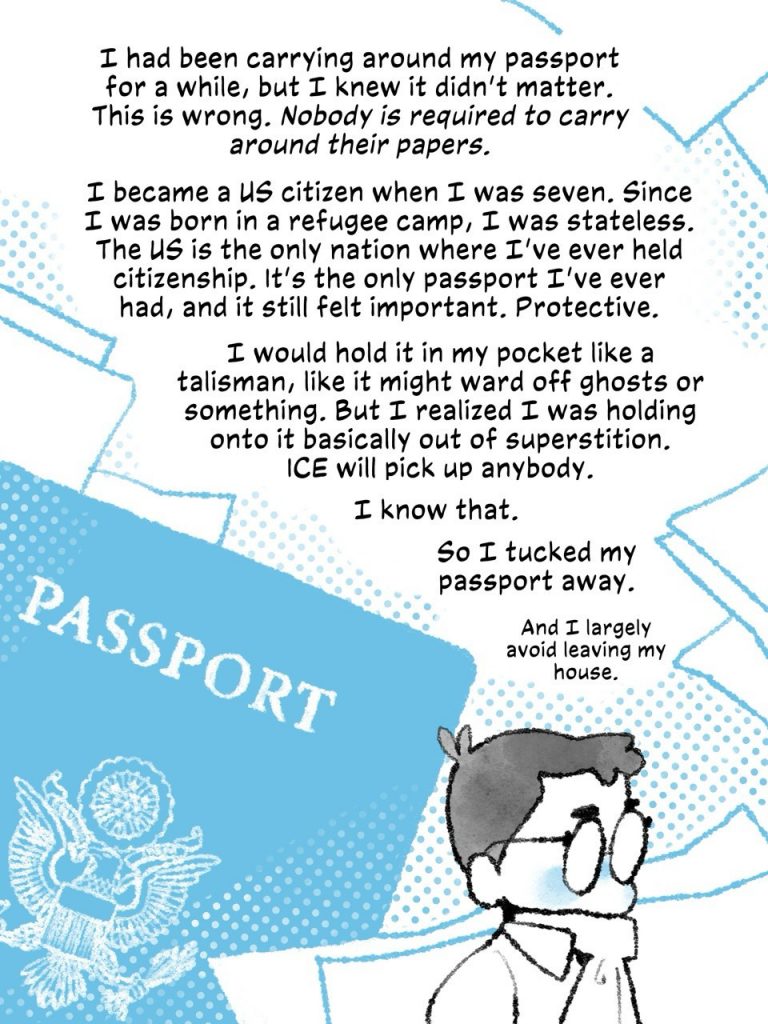

Bivens said his typical response when people ask how he’s doing is he’s “surviving,” and that’s a pretty good synopsis of where members of the Minneapolis comics community are mentally and emotionally right now. But how each person is doing ranges depending on their situation. Nguyen is a naturalized citizen from a family of refugees, and that comes with a fear of what could be waiting for them each time they step outside. Others have people in their lives who are directly connected to this, like Cannon, whose son was born in another country and wife is a teacher of students who could be targets of ICE operations. But everyone is on edge simply because of how omnipresent the government’s presence is.

“All I can think about is what is happening to our friends and neighbors,” Walz said. “I see it outside the window where I teach part time. They drag people out of their cars and homes and all we can do is run out and blow our damn whistles.”

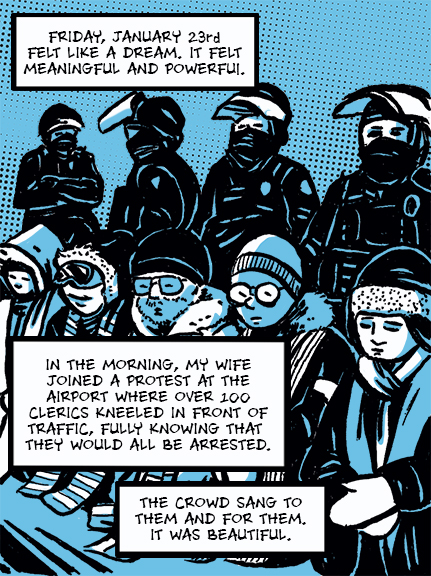

That’s understandably made a major impact in their daily lives. Some of the changes are even familiar for non-residents, as no one is immune to doomscrolling. It’s more than that, though. Some of these creators and their families are putting themselves out there, whether that’s volunteering, protesting, or supporting the local businesses most affected by the tragic events of this operation. It all wears on them, though, as a pervasive sense of dread saps their energy as they just try to live.

But it extends beyond that for some.

“I think my overall mental health has taken a nosedive, which is true for most of us,” Nguyen said. “I’m also a little exasperated, to be honest. This administration has been talking about denaturalization basically as soon as Trump took office, so I’ve spent the entire last year already pretty on edge about everything.”

“I could manage it fine, but then I started touring a bit for work. That’s when I noticed I was super travel-anxious in ways I’d never been before. ICE had already been abducting people without due process. There had already been a bunch of casualties,” Nguyen added. “I’m glad people are coming together over this now. That’s wonderful, and I hope we can keep it up. But personally, it’s weird to know that this feels personal to more people only now.

“It felt personal to me, and a lot of other people like me, a long time ago.”

Unsurprisingly, this environment has made it incredibly difficult for creators to do what they do — create. Bivens described it as “insanely difficult.” Cartoonist Brandon De Pillis said it’s “extremely challenging.” But it can also result in a sense of creative nihilism, if only because, as Cannon put it, “there’s always the sense that making funny books when the world is burning is an absurd and meaningless undertaking.” Maybe that’s part of the reason Nguyen said it “feels like wading through a swamp, creatively” right now. But everyone’s doing what they can to navigate those feelings, even as they continue feeling them.

“I keep reminding myself that what I do is work, the way anybody else clocks in at their jobs,” Nguyen said. “It may not feel important in the grand scheme of things, but it’s how I sustain myself.

“That should be enough.”

This occupation is affecting creators every day, but it’s also bringing out the best in the community, as comics offer them a way to confront the emotions tied to this experience.

“For me, it’s exactly what I need to be doing right now,” Walz said. “I have spent so many days protesting, screaming, and just wanting to feel like I’m doing something positive….to feel like anything I’m doing makes a difference. Making these comics has helped me feel more centered and focused.”

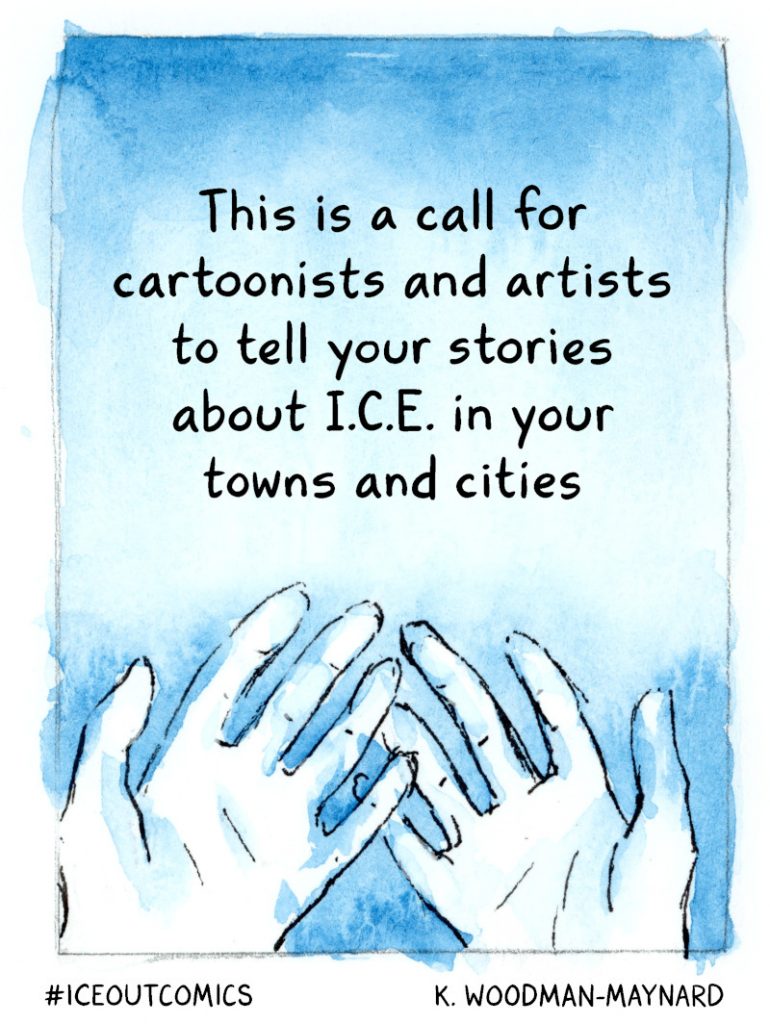

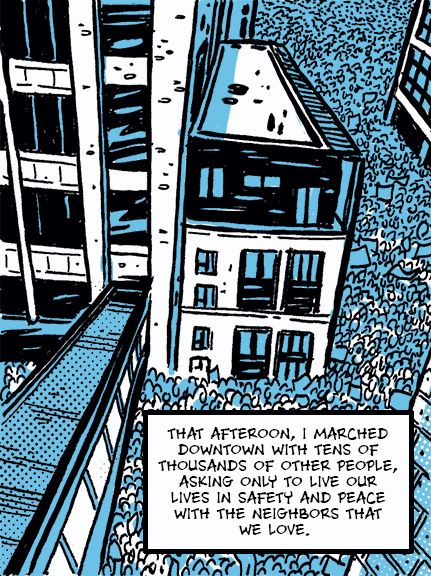

The comics Walz is referring to are the ones tethered to the ICE Out Comics initiative. Rooted in a comic area cartoonist K. Woodman-Maynard did about the experience for the Washington Post, ICE Out Comics was a project started by Woodman-Maynard, Walz, Nguyen, and Nate Powell designed to get artists and cartoonists affected by ICE’s efforts — both in Minneapolis and beyond — to tell their stories through comic strips.

As Woodman-Maynard noted in a post about ICE Out Comics, there were constraints built into it in the hopes of simplifying the process and message. Each comic should use a consistent hue of blue, it needs to be four panels in length, they recommend a 3:4 aspect ratio, and posts should include hashtags like #iceoutcomics to unite them. They want it to feel like a collective effort, and so far, it’s generated a huge response from the comics community.

“It’s incredible. 149 comics created in under two weeks from all over the country and world!” Woodman-Maynard said. “We created the spark and structure, but it was just the right time — cartoonists were ready to speak up! I think a lot of people were feeling helpless and angry, so this gives us an outlet for that.

“And cartoonists hate bullies.”

It’s given the creators of ICE Out Comics something positive to focus on. Nguyen views it “as a means of record-keeping within our respective art, but also as a means of connecting with a greater community of concerned artists and cartoonists.” Everyone involved just wants to contribute however they can, and ICE Out Comics — and the response to it — has offered both Minneapolis-based creators and those outside the area a space to do just that.

“I know how to make comics, and like most Minnesotans that I come across, we’re all just using our skill sets to help others right now,” Walz added. “We’re all fighting in the ways that we know how.”

It’s become much bigger than just its founders, of course. Take De Pillis, as an example. The cartoonist was already participating in the initiative in an effort to raise awareness in what’s happening in the area, but taking part became even more meaningful after Pretti was killed.

“The next morning, I got up and did a new comic about feeling ineffectual in the face of Alex’s death,” De Pillis said. “When I finished it, I teared up. It was cathartic. I felt useless and I wanted to be honest about it.

“When I posted it, I didn’t realize how many people felt the same way.”

The raw emotions tied to these comics ensures they can be a challenge to make. That’s something Woodman-Maynard readily admits, even if she knows the end result is worth it.

“It can be really, really hard to make these comics,” Woodman-Maynard said. “Part of me just wants to shut down and not create, but the other part of me shouts that this is vital to capture and to share what I’m seeing. And once I make a comic, I usually feel better. I’ve heard this feeling of catharsis from other cartoonists as well.”

That isn’t the only challenge Woodman-Maynard has faced. The ICE Out Comics initiative has become a much bigger effort than any of its founders likely imagined it would be. It’s ensured that the cartoonist has had very little time for her regular work, something that has been difficult to navigate.

“I’ve been spending the majority of my time on ICE Out comics over the last two weeks since it started,” Woodman-Maynard said. “I’ve created six comics, managed so much social media activity, inquiries, and press. My graphic novel has taken the backseat which I don’t love, especially as I have a script deadline in March.

“I’m lucky to have a flexible work schedule, but I am missing — and needing — to get back to my normal routine for stability.”

While she has help in managing the social media presence of this effort, between ICE Out Comics and the constant conversation about what’s happening in her city, it can feel “pretty all-consuming” to Woodman-Maynard. It’s a lot to handle, both because of its significance and the stories this effort has unearthed.

“To be honest, I’m struggling. It’s stressful to facilitate something that’s taken off like this in such a short amount of time. My initial post about it has over half a million views,” Woodman-Maynard said. “And hearing and seeing what’s going in my city — and reading it in the ICE Out comics — is painful and scary.

“But it’s also heart-warming to see the city and cartoonists come together.”

That’s the flip side of all the time and heartache that has come with the ICE Out Comics effort. While it’s painfully time-consuming as well as painful in a more traditional sense, it’s also been immensely rewarding for its founders.

“The responses have been completely overwhelming in the best possible sense,” Walz said. “Almost immediately, we had artists from around the world offering to draw stories for Minnesotans that just wanted to get their truth out into the world. I really think that most artists are just looking for an excuse to speak to the moment and to feel like they are using their voice for something positive.”

While the comics community in Minneapolis has stepped up with ICE Out Comics, they’ve been doing a lot more than that. As several noted, it isn’t just comics they’re creating; many are helping form support networks for the people in their lives. Like Nguyen said, “Everyone is showing up for their respective neighborhoods in a lot of ways beyond their art, just as neighbors and citizens.”

Art matters, but so does helping the people you know — and those you don’t — understand that you’ll be there for them when they need it most.

When I reached out to each of these creators, my questions were built on what I already knew about the situation and environment. And to be honest, what I know is barely enough to work from. It comes from the same resources that are available to everyone else. Social media. The news. Conversations with others. The usual. While that gives me a framework, it isn’t the same as being there and knowing what it’s like to live through this occupation.

That’s why I wanted to give everyone I talked to space to share the kind of insight only residents would have. I did that through one final question, as I asked each person, “What’s something you’d want people to know about what it’s been like in the area since ICE first made its presence felt?” My plan was to work these answers into the narrative as I would any other quote used within. But after reading what each person had to say, it just felt wrong.

That’s why, to close, I wanted to share each person’s answer to that question in full, as their responses underline how even in the face of the great adversity and near-constant fear this situation has created, hope continues onwards, whether you’re a comic creator or not.

K. Woodman-Maynard: I’ve never seen a community come together in such a unified, supportive, and brave way. Although it’s awful what’s happening, the unity of purpose is one of the most powerful things I’ve ever witnessed in my life.

Trung Le Nguyen: It’s weird to say this, but while everyone is very tense, there really is this incredible sense that all of us are on the same team, everywhere. I ended up connecting with people, with neighbors, I’d never spoken to before. Minnesotans have a reputation for being a little socially guarded around new people but very eager to help any stranger dig themselves out of snow and ice. And I think we’re doing that now in a different way and at a much bigger scale. It does feel very heartening in that sense.

John Bivens: Every day is tense everywhere. We’ve had a neighbor send us pictures of an individual we believe is connected to ICE going around our duplex and taking pictures while we were at our jobs. Apparently, they were doing this to all my landlord’s properties due to their family being outspoken and helpful in organizing the community. This has led to me mounting motion activated cameras for our own protection and due to us living directly across the street from a world immersion school for grade schoolers. ICE has been spotted in the neighborhood multiple times, and we know they are not above going after children and then using those children against their families. The biggest tool we have working for us is the ability to get the truth of what’s happening before the public’s eyes.

We will continue to protect these neighbors in any way we can, and we will outlast this occupation.

Brandon De Pillis: We were already a strong community-based state. ICE just solidified what was already there. We take care of each other and our community. Every morning after the George Floyd riots, people made their way to the main street, Lake Street, and would sweep and bag any debris. Whole families took part. You never saw that on CNN. Now the world knows who we are. We’re a small town in a big city. We take care of each other.

Zander Cannon: Honestly, it feels like it did at the start of COVID. It feels stressful to go out, you keep to yourself, there are people who can’t leave their homes, and of course, people are dying. It’s horrible, and it has also brought out the best in people. People making food deliveries, schools quickly setting up online learning for people who are targeted, massive turnout to protests…all the stuff you see on the news. What’s scary is both that you forget that it’s not like this everywhere, and that it could be, at any time.

Jason Walz: However bad you think it is, it is actually worse. Many students can’t attend school anymore. Their parents can’t leave their homes to work. We spend our “free time” either protesting or trying to figure out how to get groceries and supplies to families without being followed by ICE.

But…and here is the important part, what Minnesotans do really well is take care of each other. People would be amazed at how quickly local businesses switched over to becoming hubs for resources and distribution, how much money is being raised for those in need by individuals and grassroots organizations, or how effectively we have figured out how to disrupt ICE activity to try and save lives.

We got this.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this article and would like to read more like it, or to support the work that went into it, consider subscribing to SKTCHD. The site is entirely independent and ad-free, with subscriptions funding everything on the site.