The Story Behind Top 10, From the Artists Who Helped Define It

While Watchmen is generally considered to be Alan Moore’s best work, that doesn’t mean it’s everyone’s favorite. Watchmen is undeniably great, an important work in the history of the comic book medium. But people are unique creatures, and our preferences are linked to more than just quality. For some, it might be a superhero universe story, like Batman: The Killing Joke or his time on Swamp Thing. For others, it’s originals like From Hell, V for Vendetta, or The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. If you suggested one of those was your favorite, odds are, most would understand even if they might prefer another. There isn’t really a wrong answer, per se.

But there are atypical ones.

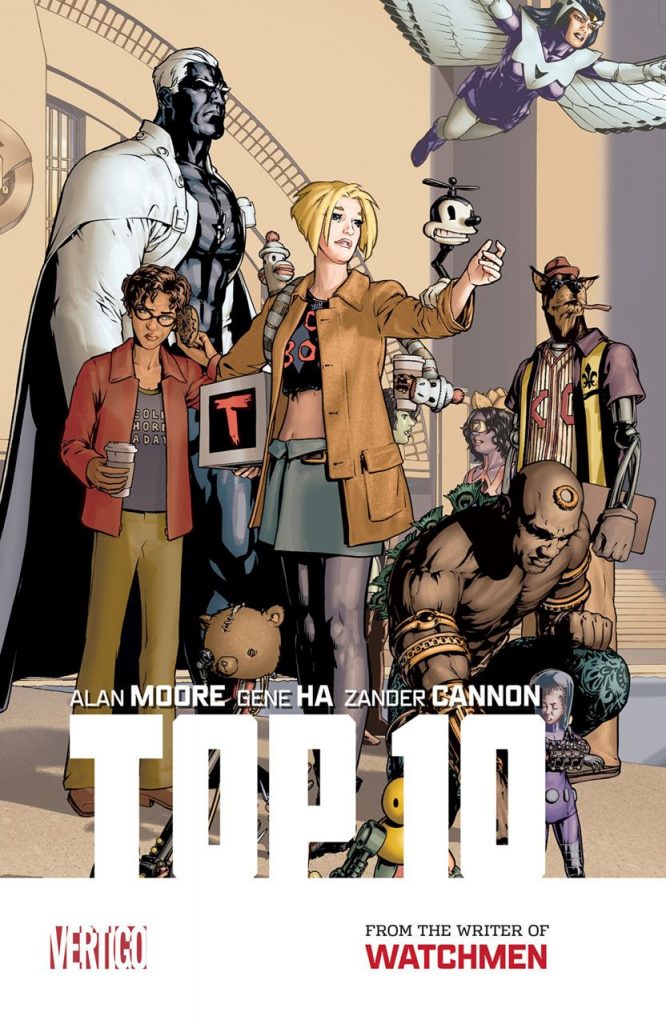

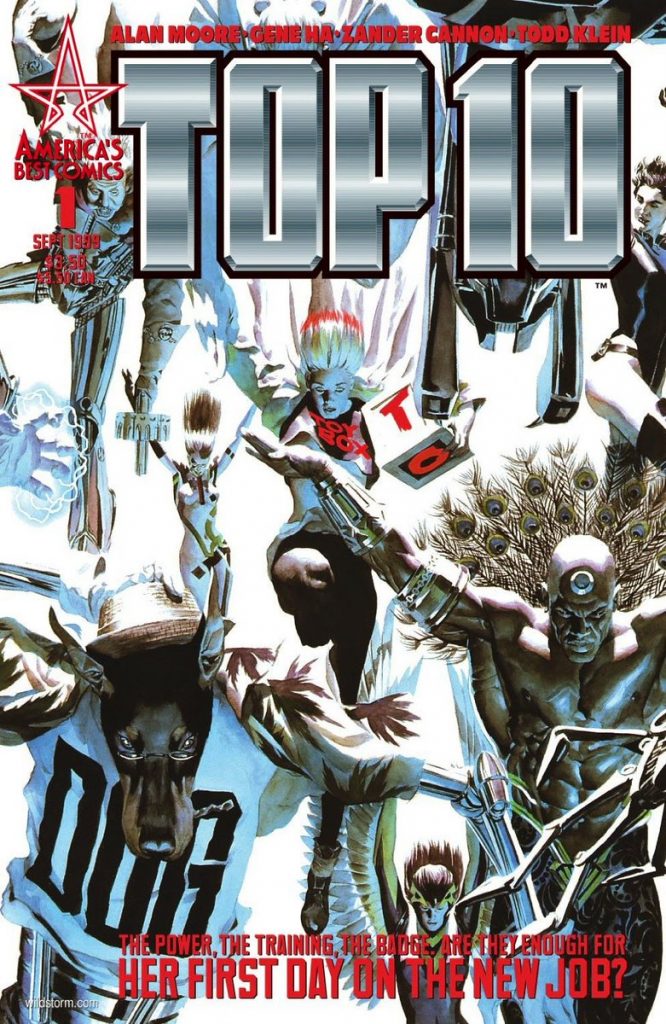

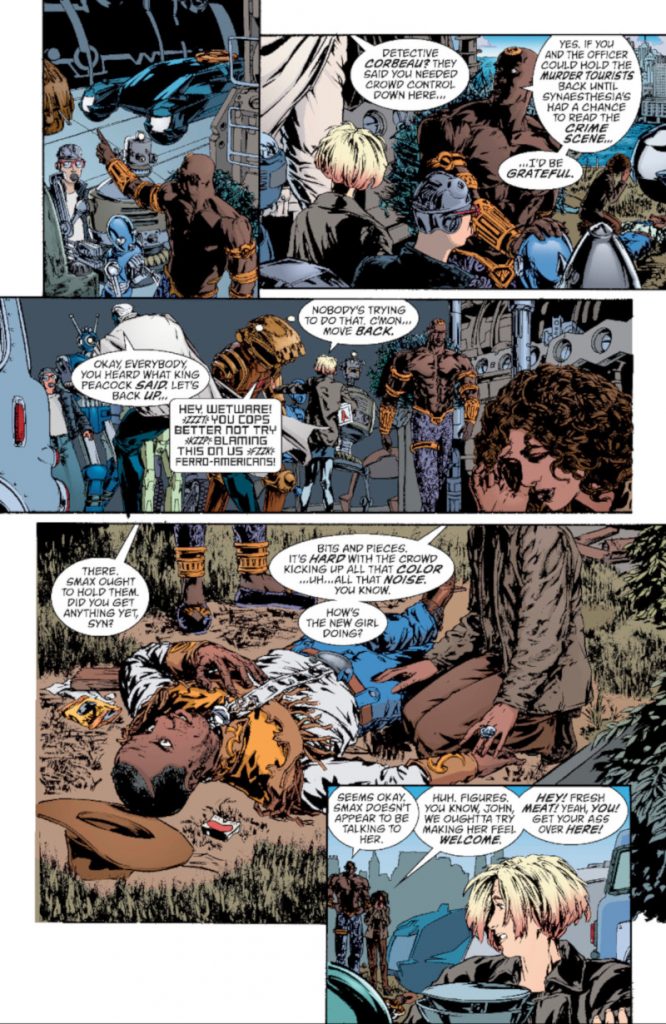

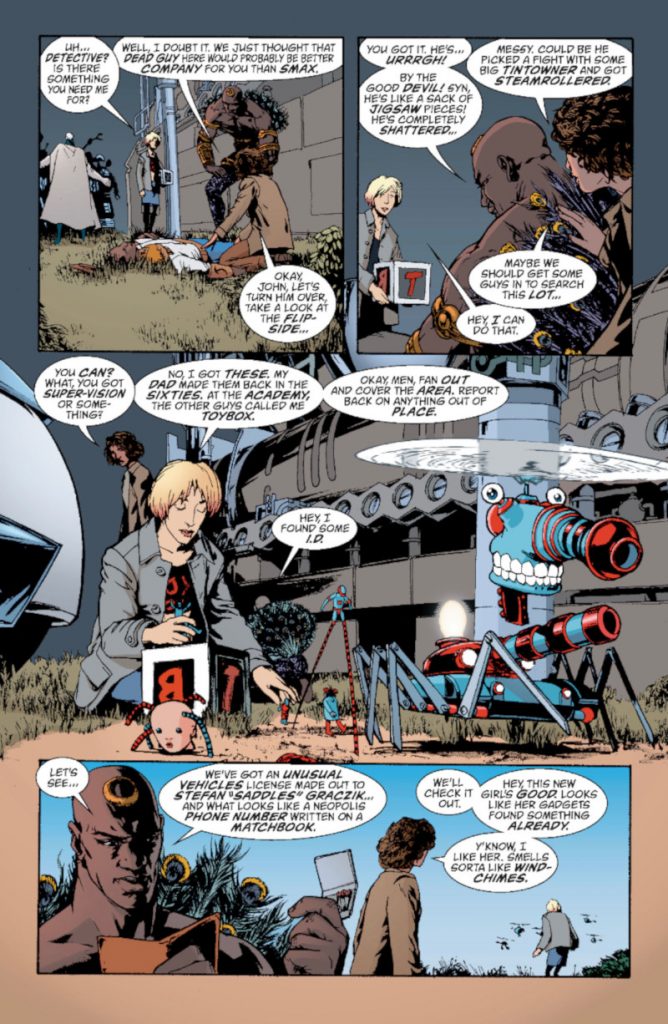

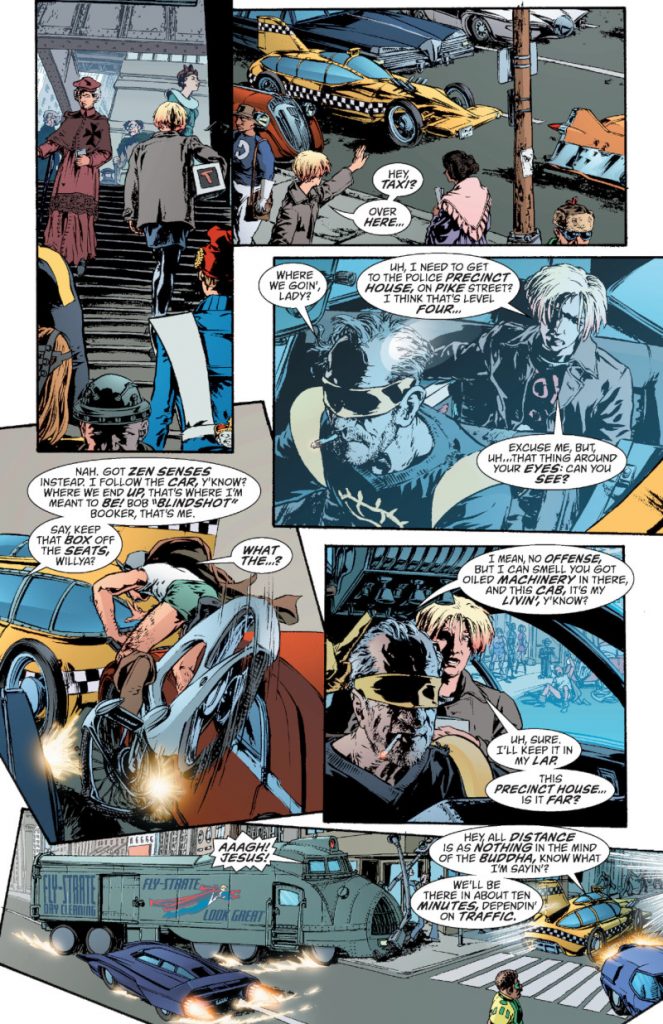

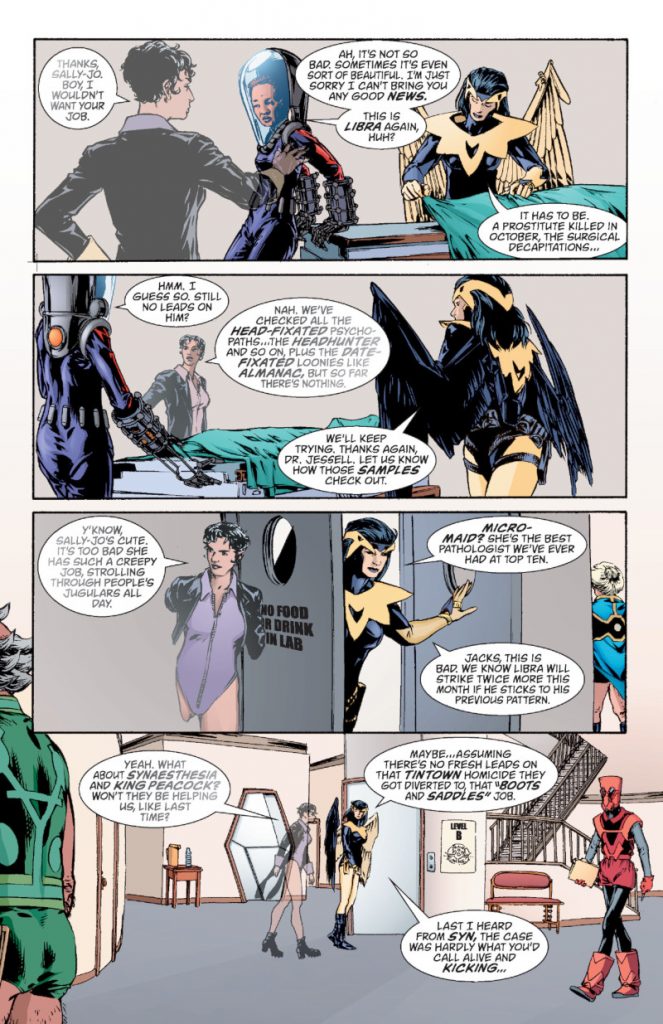

For example, my favorite Alan Moore project is Top 10, the America’s Best Comics 1 series about the police force of a fictional city called Neopolis. It’s a metropolis filled with superpowered types, and the series follows varying officers and detectives as they contend with the unique challenges that presents. Drawn by the art team of Gene Ha and Zander Cannon with colors by Wildstorm FX and letters by Todd Klein, Top 10 was the first time I’d ever read a comic that existed within the police procedural genre, with a loaded ensemble of cops, criminals, and curiosities. It wasn’t just its complex and appealing core cast that was a draw. Bit players shined in a rare way, to say nothing of the omnipresent Easter eggs the series is famous for. Don’t get me wrong: people liked Top 10. It even won the 2001 Eisner Award for Best Continuing Series. 2 But it always felt overshadowed by its peers in the ABC line, like Gentlemen, Promethea, and Tom Strong.

That’s too bad, because its exploration of the Tenth Precinct of Neopolis — the police station nicknamed “Top 10,” where the cast and much of the story is based — and its frequently shifting caseloads is loaded with drama, humor, and astonishingly poignant moments. It’s a riff on the ideas of superhero comics and procedurals, and through characters like Toybox, Smax, Kemlo Caesar, Irma Geddon, and an array of others, we’re given something that is uniquely effective at both of those genres.

Perhaps the thing that makes this story pop most for me is just how unusually in sync the creators involved felt. This isn’t to diminish any of Moore’s other collaborators — needless to say, they’re all brilliant — but there’s just something special about how this team worked. It never felt like individuals executing their roles; instead, it read like a hive mind formed to tell exceptional comic stories, delivering a singular vision like a cartoonist would but as a disparate group of individuals with complementary strengths and weaknesses.

Also: It’s just a hell of an entertaining comic, and one that only gets better with every read.

While Top 10 grew beyond its initial 12-issue story — with Moore and Ha teaming up for Top 10: The Forty-Niners, Moore and Cannon bringing an immediate follow-up in Smax to life, and Ha and Cannon delivering an abbreviated second season for the series, 3 each of which was fantastic — that original volume was just uncommonly great, having a je ne sais quoi to it that made it an extraordinary series. Ever since I read it, I’ve wondered how they accomplished the wonders of Top 10, and what it took to create such a special story. So, recently, I did what I do: I tried to find out.

I sat down with both Ha and Cannon to discuss the story behind Top 10 from their perspective, and how the two worked with Moore to craft this remarkable series. It originally started as a much different piece, one that just found me revisiting an old favorite with insight from two of the folks behind it. Instead, it became a retrospective about a collaboration of a rare quality, the comic that united them, and how certain projects can change everything for you — if you let them.

How the Team Came Together

Gene Ha had been a big fan of Alan Moore for a long time, with his admiration of the legendary writer dating back to high school. By the time he became a pro, working with Moore was a dream. It was also one he was unsure of ever reaching, despite having a connection in his friend and fellow artist Alex Ross, who was drawing covers for Moore’s Supreme at the time. At some point during that run, Ha admitted to his pal how much he wanted to work with the writer himself. That’s when Ross gave him some simple advice that proved to be life-changing.

“(Alex) just said the logical thing of, ‘Well, if you want to, why don’t you go after it?’” Ha told me.

“So, I did.”

The only problem was, by the time Ha started making inroads at Maximum Press — the Rob Liefeld created imprint where Moore was based at the time — the entire house “collapsed.” The artist could have taken that as a sign. Instead, Ha followed Moore over to Wildstorm, contacting the main editor there, Scott Dunbier, to hopefully pass art samples on to Moore. It worked. Moore liked Ha’s art, giving him “the nod as a possible artist” for one of his upcoming titles at America’s Best Comics, the imprint the writer was launching at Wildstorm.

“When I first saw the proposal of, ‘What do you want to do with America’s Best Comics?’ I thought, ‘Wow, I would really like to draw Promethea. And I really hope I don’t get asked to draw Top 10 because it’s all giant city backgrounds and crowd scenes. That’d just break me.’” Ha remembered. “At some point, I got the phone call from Scott saying, ‘Alan would like you on Top 10.’”

“I went, “Not Promethea?’” he added. “But I was going to do it.”

The good news is, Ha had plenty of prep time — maybe as much as a year, per the artist — which was necessary considering all the work the title asked of him. He made it halfway through the first issue before realizing the artist he wanted to collaborate with on the project initially wouldn’t be available. That was a problem. As Ha put it, he’s “not super-fast at anything in comics except faces.” With an extremely challenging project ahead, soloing it seemed as if it could be a painful experience.

That’s where Zander Cannon comes in.

The pair had met years before at a sparsely attended signing in a comic shop in Indiana, an event that gave the pair time to realize how much they enjoyed each other. They kept in touch, and a year or two later, Ha moved to Cannon’s home of Minneapolis. When the other artist fell through, Ha realized the “brilliant” Cannon would be a perfect partner on Top 10.

“So, I asked him to join me.”

How it played out means that Top 10 as a series has a couple before and after moments you can see within its pages. The first happens early on. If you ever felt like there was a change in how the series reads visually within the first issue, that’s because the initial 12 pages were drawn by Ha alone. The artist described those pages as “so relentlessly nonstop” compared to his work with Cannon. While the initial pages followed Moore’s scripts, Ha believes in retrospect that he “sometimes would jam too many things in at the wrong time,” causing it to not “flow well” from a storytelling standpoint.

And if there’s one thing Ha emphasized that he’s not fast at, it’s layouts. It was a bottleneck in the process. Thankfully, layouts were an area of strength for Cannon. The incoming artist was only in his late 20s and didn’t consider himself uniquely adept at anything at the time. But even if he was surprised by the offer and the belief Ha had in that specific skill of his, he wasn’t about to pass on the opportunity.

“I’m not the expert in anything, but if you are asking me if I want to work on this Alan Moore project, you are damn right I do,” Cannon remembered.

“Then we jumped into it.”

How They Worked Together

Much of the design work was complete before Cannon signed on, as Ha had to define the main cast before interiors could start. Cannon did have an impact there as well, though. Ha noted that his collaborator “designed a lot of the characters who didn’t show up in the original proposals,” like the two-faced 4 dispatcher Janus or the quintessential Cannon design for shark-headed lawyer Carl Fischman. Much of this happened quickly and even on the page, though, because the demands of the project were significant and fluid.

Their collaboration on the title was as well, and it wasn’t just the artists fine-tuning their approach throughout Top 10. Ha told me that “to some extent, Alan figured out what he wanted to do, too” as the series progressed. That’s where the other before and after comes in. Early on, everyone was still feeling each other out. That’s part of the reason Toybox — our point-of-view character in the first issue — suddenly looks like she was drawn by someone else entirely on page 13 of issue #1: she was! That was Cannon’s first page on the book, and an example of the artist providing finishes.

“If you look early on — in both issue #1 and #2 — you’ll see some scenes where it’s obvious Zander was doing finishes,” Ha told me. “It looks a little bit disjointed as far as style goes. We didn’t really have it down.”

You can see everyone getting more aligned in terms of processes as the book goes along. Part of that was just beginning to recognize each other’s strengths.

“By the end of the first issue and a little after the beginning of the second, it became totally clear to us that Zander’s insanely good and fast at layouts, storytelling, reading the script, interpreting it, and figuring out nuances I wouldn’t see,” Ha shared. “And for consistency of style, anatomy, perspective, backgrounds, and stuff like that, I can do things that Zander can’t do.”

It wasn’t just their talents deciding that, either. The pair quickly realized that their workflows existed in conflict. Cannon shared that they “had almost the complete opposite approach.” Certain steps in Ha’s process didn’t even exist in Cannon’s. Others were just in different places. That made the setup where he did layouts while Ha penciled and inked even more appealing.

Hashing all this out was made easier by the fact that they lived in the same city, with studios right next to each other. That allowed the pair to quickly discover the way to tackle Top 10 in the most complementary way possible. And the method they settled on was simple.

Cannon said his approach on Top 10 was “workmanlike,” focusing entirely on clarity of storytelling. He believed it was important to keep the layouts as traditional as possible, if only because the story itself was so fantastical it needed to be grounded in reality. While they didn’t earn an official credit for Cannon drawing layouts and Ha tackling pencils and inks until the sixth issue, Cannon estimates that they were fully locked in with that being the structure by the third issue. 5

Cannon said he would usually take a “pretty sloppy” run at the layouts on a piece of paper, then he would “put it on a light table and trace it” to effectively give Ha a character’s silhouette or even “two dots and a frowny face” to get his partner “going in the right direction.” His goal was to deliver something as “spare as possible” to allow for maximum flexibility. In short, Cannon gave Ha “pure composition and pure storytelling,” at which point Ha finished the pages, making the magic happen in the process.

“Once we settled into our working process, Gene’s brilliance is what’s on display,” Cannon emphasized.

There was another important reason this process was necessary. Alan Moore’s scripts are famously dense — Cannon described his reaction to reading them by saying, “Jesus, this is covering literally all the bases” — and because of Ha’s admiration for the writer, he “was very reverential to the scripts.”

“If you can get a hold of an issue #1 script and then compare it to the first 12 pages of #1, I am following a recipe religiously like a chemistry student,” Ha told me.

That density can result in similarly dense storytelling. But while Ha stuck to the script, Cannon saw opportunity in the “basically unedited” single draft they would receive from the writer. And when I say, “single draft,” I mean there was for the most part only a first draft, per Cannon, which is why the bases being covered was so important. No one needed to ask “any clarifying questions,” Cannon told me. You just needed to read and interpret it, which he found freeing as someone fluent in the language of Alan Moore.

“Zander was the one who was able to tie it all together and essentially act as a translator between two of us in a way,” Ha told me. “Zander was able to figure out the storytelling build of Alan Moore, and then figure out a Zander Cannon way of telling the story more efficiently sometimes.”

“The nice thing about (Top 10) was it wasn’t this spare, tense drama. It was just a fire hose of junk out on the page,” Cannon added. “If you had to course correct a little bit to fix a problem or whatever, it was no big deal.

“It was part of the vibe.”

Ha mentioned that Cannon believed “Moore was reverse engineering” the script, down to the writer drawing “a thumbnail to all the layouts,” word balloons, figures, and all. That way when he sits down to write a script, “he’s literally describing his thumbnail.” The reason for that, Ha said, was how systematic the scripts were. It worked too well visually to not be the case, as it was “not something you can easily do when you’re just doing it from your imagination.” This made sense to Ha, if only because, as he put it, “Alan Moore is a comic book artist.”

Walking and Talking

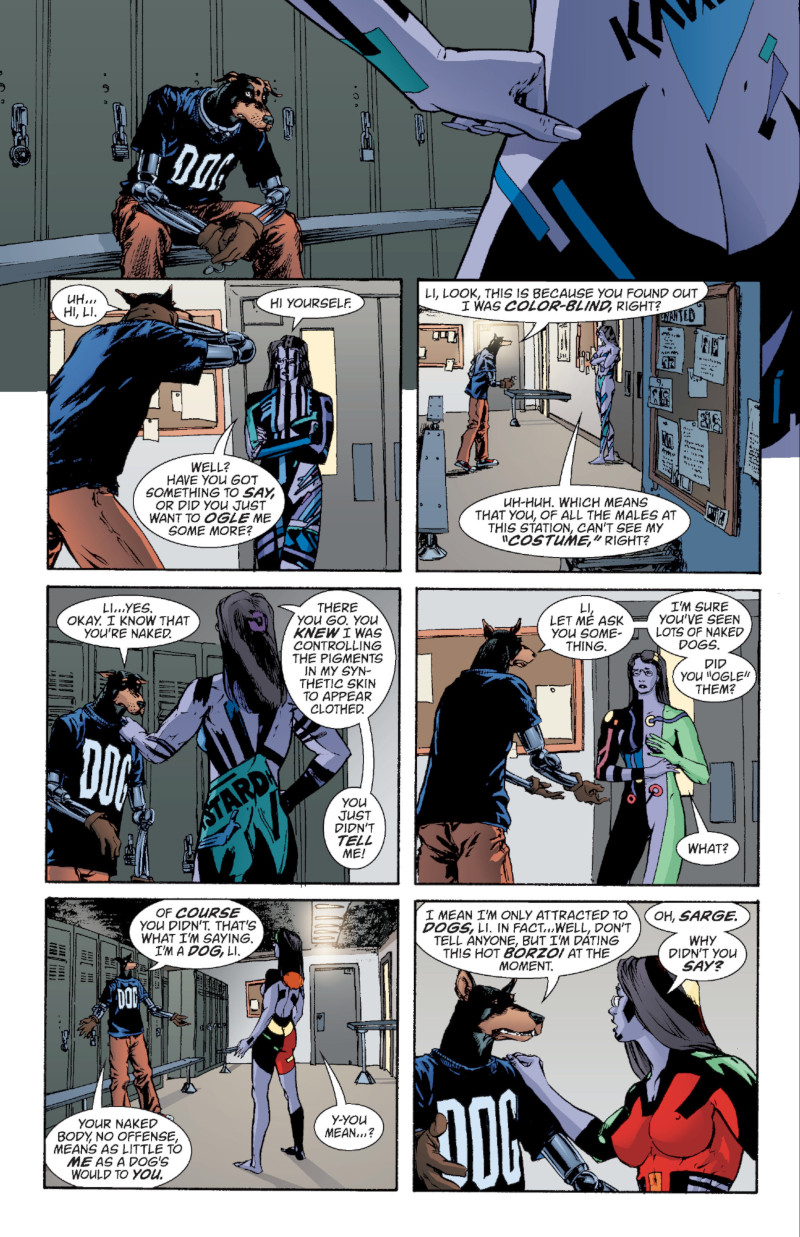

One of the most unique aspects of Top 10 was how it incorporated the visual language and structure of procedural TV dramas. It isn’t the only comic to ever do that, but it was one of the best at it. And the structural part is obvious. Most issues oriented on a case or several cases, as the varying detectives and police dealt with problems both small and large. 6 There was a cleanliness to its issue-by-issue narratives that reflected police dramas of the time, like Prime Suspect, NYPD Blue, and Homicide: Life on the Street. 7

But my favorite part of the visual language side is how perfectly it incorporated “walk and talks.” That’s a technique common to television procedurals that finds cast members quite literally walking and talking through their precinct or whichever location they’re in, before they visually connect with other cast members who continue a different conversation from there. Top 10 uses this structure incredibly well, and it turns out, the very idea was rooted in the original pitch and the scripts themselves.

“His scripts are very detailed. He obviously has that vision in his head of the camera as a character moving in and out of conversations,” Cannon said. “And he was attempting something that was so complex. In this case it was…I wouldn’t say new to comics, but the idea was that we were specifically trying to emulate something that is done in film and doing it in comics.”

“So as far as he can take it, he still had to hand me the ball because it’s not all the way there. I had to take it and make sure our virtual camera was in a place so you can go, ‘Okay, there’s the end of their conversation and here’s the beginning of the next conversation,’” he added. “You can’t underestimate how tricky that kind of stuff is and how much effort you need to put into it.”

Ha noted that one advantage to this was Moore wasn’t used to ensembles, so this “walk and talk” element helped act as connective tissue to disparate stories and arcs within the title. It was tricky to pull off, but it was a crucial and necessary element to the series.

“Alan did not do team books, in general, until he realized that he could use that trick to transition from one team to another and keep all the stories connected that way because they’re all hanging out on this side of the precinct building,” Ha said.

From a dialogue and character standpoint, it was easy to execute. Write and draw characters walking and talking until they enter a room or area, at which point they handoff to others who do the same thing. Rinse and repeat. For Moore and Ha, it was no big deal to let the chips fall where they lie, letting scene logic win out over painfully mapping out Top 10’s precinct building or anything. Unfortunately — or perhaps fortunately — Cannon could not stand for that sort of laissez-faire approach.

“I did not try to make the building consistent beyond the lobby. Zander’s the one who actually began drawing maps,” Ha told me. “Zander’s the one who worries about stuff like that.”

This was necessary in Cannon’s eyes because of just how prolific Moore was at the time. He was writing a lot, so when it came to Top 10, “he was (often) just winging it.”

“I had to be like, ‘Okay, so based on what we’ve done here, what is the layout of this place? What’s on this level? What’s on the upper level? What’s up on the lower level?’” Cannon shared.

That only got him so far, of course. Sometimes he’d receive a script where “all of a sudden there’s an office right across the hall from something” that wasn’t there before, at which point Cannon would shake his fist and say, “No, it’s over here!” Internally, of course. He’d just move on and hope no one would notice, even though he believed that some level of logic to the building would add to the realism. Plus, he thinks “that kind of character business is fun.”

“But of course, it drove me nuts because there was maybe 80% compliance from (Moore).”

The Easter Eggs

One place where there was compliance from Moore — and then some — were the Easter eggs the series is famous for. Throughout Top 10’s pages, you can find appearances from basically every variety of superhero you can imagine, often used in comedic fashion. It was baked into the concept. After all, Neopolis was a city of superpowers, so who else would its citizens be? But this is where the crowd scenes came into play, something most artists dread. Maybe that’s why Ha told me that, “Honestly, as much as I could, I tried to avoid” those elements.

“But if I felt like the scene would be improved by throwing in details like that, just even to give the feel that you’re in a city where things are happening, I would throw it in,” he added.

One major difference between Top 10’s crowds and ordinary crowd scenes is, as Cannon put it, most are “just regular people.” That’s boring. In Top 10, Cannon found himself “drawing Frog Thor and Jimmy Olsen as Turtle Boy and all kinds of weird junk, so at least it’s worth it.” They had fun with it too. They’d try to connect concepts with characters, like in issue #8 when a car filled with rubbernecking individuals staring at a traffic incident was comprised of literally rubbernecked individuals like Elongated Man, Reed Richards, and Plastic Man. They wanted to entertain themselves — and the readers in the process.

Some of these Easter eggs came directly from Moore’s script. Others came from the artists. How many came from each shifted as the series progressed.

“I’d say that two thirds of the background characters in the first issue were in Alan’s script, and by the end, one third were,” Ha said. “The trick is that he would sometimes just give a theme for characters in the story or in a scene, but then he wouldn’t list any examples.”

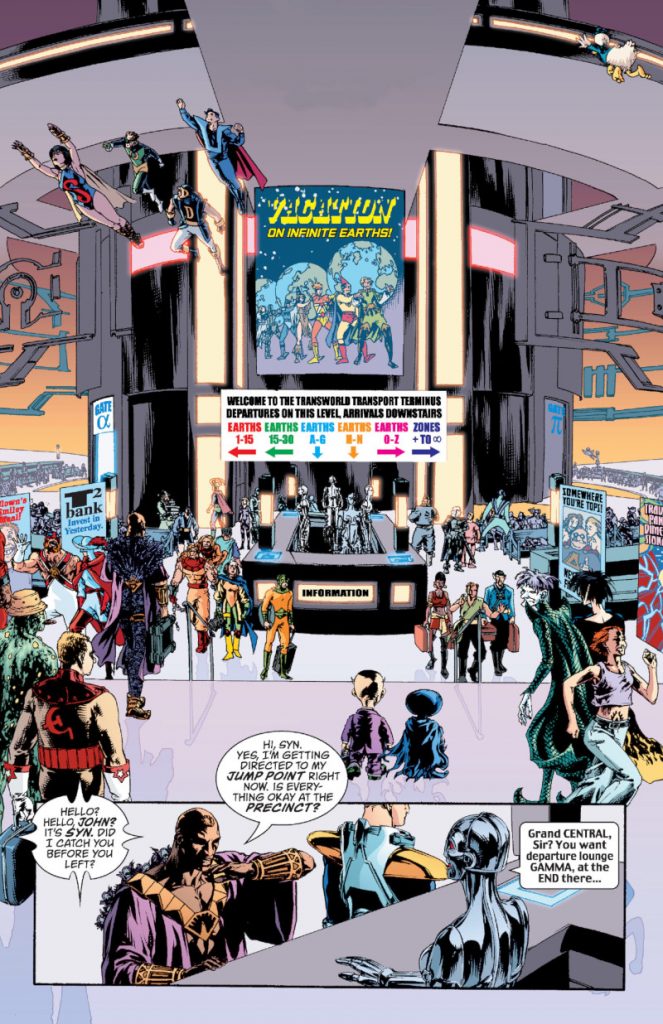

A perfect illustration of that came in one of my favorite Easter egg-laden scenes, as Top 10 detective King Peacock goes to a transit station called the “Transworld Transport Terminus,” where anyone can travel to a parallel dimension. Think of it as an interdimensional airport, in a way. There’s a portion of one page that displays the lobby, and it’s a masterpiece of superhero Easter eggs. It was also just Ha riffing, for the most part.

“I don’t think Alan listed any character examples. He just said, ‘Throw in characters known for traveling between dimensions,’” Ha said. “And that was the last page of that batch of script, so I threw in as many as I could imagine, especially having fun with making fun of Alan. So, I threw in a lot of characters he’d created.”

While the artist told me that a lot of the “funniest” details and backgrounds throughout the series came from Moore, he was “proud” of the tourism poster he created for the Terminus that shows a conga line of Crisis on Infinite Earths characters with the tagline “Vacation on Infinite Earths!” overhead.

It really is a beauty.

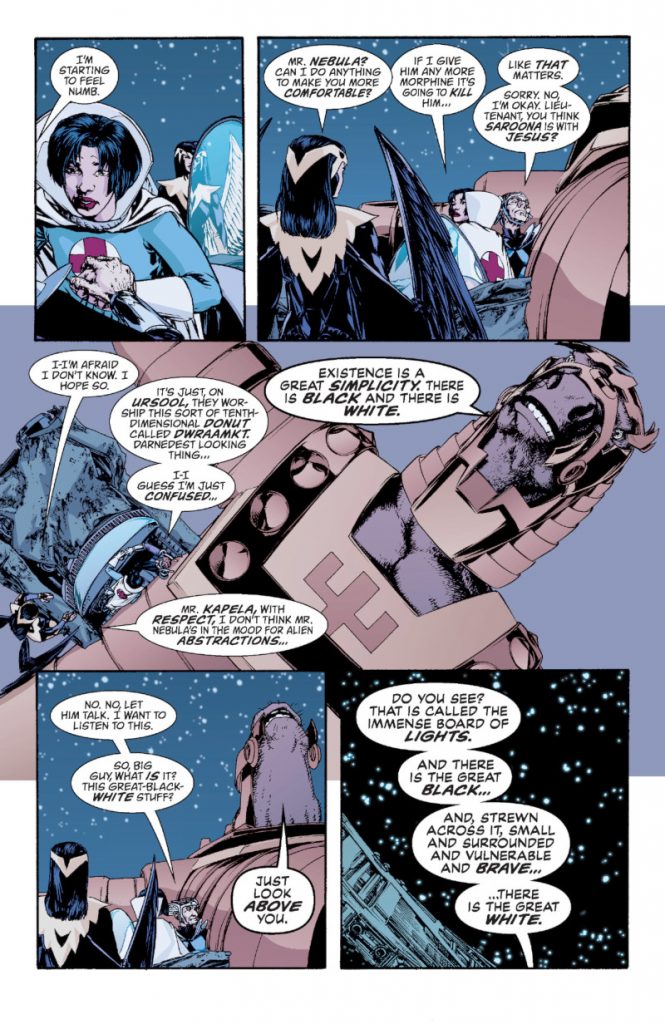

The Great Game

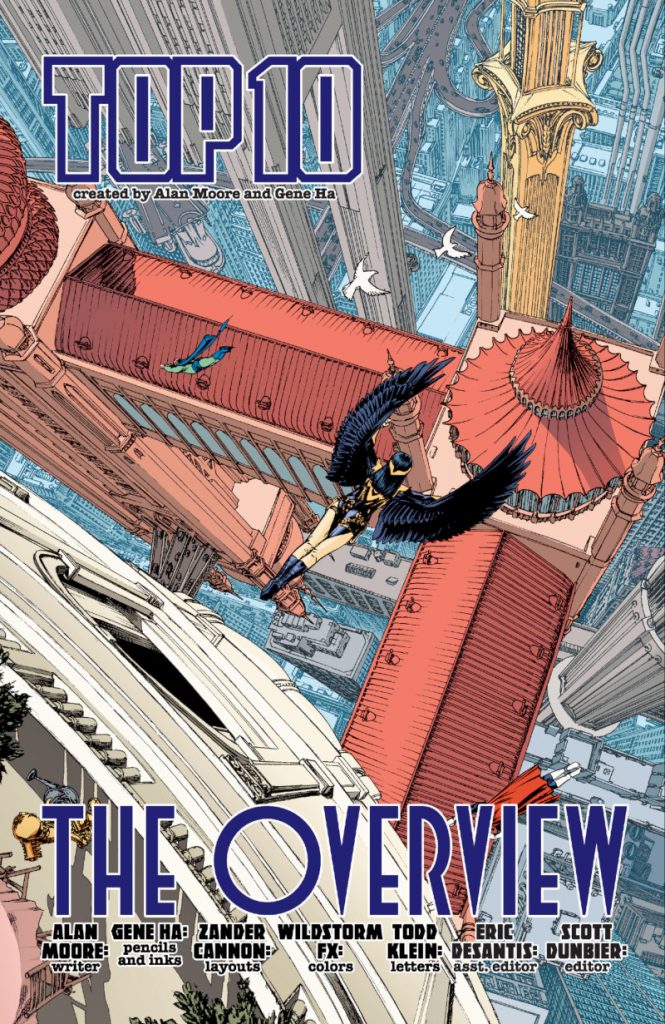

If there’s one issue that Top 10 is famous for, it’s #8. While it’s officially titled “The Overview,” I personally call it “The Great Game,” a nickname that connects to its A story. It finds officer Peregrine dealing with a traffic incident, in which a giant, anthropomorphic horse — a “Great Gamer” named Kapela — “riding a Thunder Road” crashed into a couple teleporting in from an entirely different area, grievously or fatally injuring each of them in the process. What sounds like a standard traffic incident quickly turns into something far more, with Peregrine needing to solve what really happened and, more importantly, help ease the journey of those involved into the afterlife.

It’s one of the most beautiful, poignant issues I’ve ever read, and a heartbreaker that holds up decades later. That’s not just me saying that either. Cannon described it as “everyone’s favorite issue,” with Ha admitting “it feels like the finest hour” of Top 10. While it’s laden with some of the best Easter eggs of the entire series, it’s that core story and the tragedy at its center that elevates it. The story starts with wide shots, highlighting the ridiculousness surrounding the accident, but as we move closer, it only gets increasingly emotional.

“(Kapela’s) explanation of this game is, on the face of it, completely absurd,” Cannon said. “But as you zoom in and have this intimate little scene, it becomes very meaningful, sad, and impactful on the characters.”

“It was such a well written story.”

The incredible thing about this issue is it at least in part only happened because Alan Moore got sick shortly before pages were due to the artists. I’m not trying to say that this issue was Moore’s equivalent to Michael Jordan’s flu game, but if I did, it wouldn’t be entirely inaccurate.

“What happened is, Alan had gotten the flu or something like it, and he was too sick to write the whole script or to figure out the plot of that issue,” Ha noted. “So, he wrote two pages to slow us down long enough so he could recover from the flu and then figure out what the story was.”

“(The second page) is just a one point perspective down shot of this entire city that took Gene an absolute age to draw. And that was on purpose because Alan had the flu and he was like, ‘I have to give Gene and Zander something to get them off my back,’” Cannon shared. “So, he wrote these two pages that were intentionally a huge pain in the ass to draw. That was why the story ended up focusing on (Peregrine).”

“I think the reason the story is so tight is that it starts and ends on her and her crisis of faith. That’s a great example of just playing the cards you’re dealt, being able to pivot, and then making a meaningful story out of it. Which I thought was remarkable.”

“He left himself little bits and pieces that he could play with later, but he didn’t know what he was going to do with it,” Ha added.

“And then, it turned out to be the greatest issue of Top 10 ever.”

Top 10’s Lasting Impact

Our relationship with procedurals has changed dramatically in the two plus decades since Top 10 arrived. The police are no longer broadly or clearly perceived as heroic in 2023, and for good reason. So much of the genre is considered “copaganda,” storytelling designed purely to portray police in the best possible light. That may be true, but I’d argue Top 10 still works as well as it did then, at least in part because its heroes may have been cops, but — spoilers for a twist from more than 20 years ago — so was its most significant villain.

Commissioner Ultima, the person who oversees the police across all the parallel realities, was the big bad behind one of the core mysteries in the story. That’s part of the reason Top 10 was able to dodge that trap even decades later. It had a healthy fear of the police and corruption, even as it told a story about them. Cannon believes this was at least partially rooted in the influence of realistic police shows of the time, like NYPD Blue, a series that also was skeptical of the profession even as it told stories within it. Ha described that as “pure Alan,” both because of the writer’s view of humanity in general and because of his experiences with the police in his youth. Whatever the reason, its approach resulted in a series that has aged well in that regard.

While the relationship some readers have with Top 10 may have changed over time for that reason, it still works — and works well — even though it’s rarely been built on. That’s an interesting wrinkle to it: Top 10 has never become a “franchise” as so many properties owned by DC tend to do. In fact, it’s only ever really worked with at least some two person combination of Moore, Cannon, and Ha involved. Only one other team has ever tried — writer Paul Di Filippo and artist Jerry Ordway in 2006’s largely forgotten Top 10: Beyond the Farthest Precinct — but no one else has save for the original team in Top 10, Smax (which was Moore and Cannon), Top 10: The Forty-Niners (which was Moore and Ha), and Top 10: Season Two (which was Cannon and Ha). They’re the only ones who have made it work, and for good reason: the process making it was like “putting nails through your hand,” as Ha said.

“It’s painfully slow putting in all the details, all the references, all the texture, all the bits and pieces in background characters because that’s part of what makes a Top 10 story a Top 10 story,” Ha said. “You know that the city has real life in it.”

Maybe that’s why Top 10 has had a lasting impact on the artists behind it. Cannon told me that he’s “never had more energy for a new project” than he did for Top 10. It was such a strong feeling that if he even hears a song now that he listened to while working on it, it immediately transports him back to that time. More than that, Top 10 and their collaboration on it changed the work of both artists. You can see it in Smax and The Forty-Niners, as Ha told me.

“If you look at the storytelling on something like Starman versus the storytelling inside of The Forty-Niners, you’ll see changes, which is me learning from Zander about how to just tell the story more cleanly,” Ha said. “In a sense, he gave me rules, seeing the problems in my storytelling, and then realizing he needed to phrase it as a rule to have rule-based Gene Ha understand it.”

Cannon told me Top 10 “completely changed the way I thought about writing.” It even became a calling card for him, something that shifted his perception in the industry in a real way.

“Top 10 was sort of the hub of all my work for hire projects,” Cannon said. “It was the thing that got my calls answered.”

Rereading this series and reading Smax for the first time for this project, it stood out how similar in some ways both are to Cannon’s magnum opus, Kaijumax. That’s not an accident. Cannon described that series as a “spiritual sequel to Top 10.” More than that, working with Moore helped him better understand how to weave narrative threads together and blend disparate, otherwise disengaged storylines into something extraordinary. To this day, Cannon’s amazed by it, saying, “I thought it was astonishing how (Moore) took what was commonplace in TV at the time and put it into comics.”

To be fair, though, that’s what the whole team did — together.

A lot of times in comics, you’ll read a comic from a seemingly solid creative team where something about it just doesn’t work. The artist doesn’t fully understand what the writer wants, or the writer doesn’t give the artist enough freedom to make their mark, or maybe not enough care and consideration is put into the lettering or coloring. Either that, or there’s something incongruous about it, where the sum just ends up feeling like less than the parts.

Top 10 was the opposite. Individually, Alan Moore, Gene Ha, and Zander Cannon — to say nothing of Todd Klein and Wildstorm FX — are amongst the very best to ever make comics. They don’t need each other to thrive. But working together on this singular 12 issue series, they united and made something remarkable in the process. Each elevated the work but also each other’s craft, complementing one another in a rare way. That’s what made Top 10 as good as it was. It was a creative team in the truest sense of the phrase.

A former imprint of Wildstorm and then DC/Wildstorm.↩

To say nothing of its 2000 win for Best New Series.↩

To say nothing of the otherwise uninvolved franchise continuation in Paul Di Filippo and Jerry Ordway’s Top Ten: Beyond the Farthest Precinct.↩

Literally.↩

He noted that editorial was “reluctant” to even let them do that, and it was even difficult to invoice DC for the work he did at first. They eventually settled on each taking a percentage of the page rate for the art.↩

Or extremely large in the case of the drunk dad kaiju that is Gograh.↩

To say nothing of Hill Street Blues, a series from the 1980s that was an influence.↩