Fight or Flight: Wild’s End and the Visceral Power of Storytelling

We review the BOOM! Studios series after the close of its second mini

If you asked 100 storytellers what the objective of their work is, you’d probably get 100 different answers in response. Every story is different, really, and with that comes different goals. But if you analyzed each answer, you could probably find a through line. While there are purposes outside of just this one, I think deep down storytellers want their audience to care. Whether you work on TV or in movies or in books or whatever, you want people to develop a relationship with your story, no matter if its an abstract narrative or something more direct. After all, without emotional or intellectual resonance, what do you have, really?

In comics, its much the same. Something like Saga isn’t popular because its “Romeo and Juliet meets Star Wars” or some other easily digestible high concept. It’s because we read it and we’re enthralled with the story and in love with characters like Alana and Lying Cat and The Will and most importantly Ghüs. We care about them and we want to see what happens next with them. As a reader, that’s what I’m looking for in my comic experience. I want to care about a story and its inhabitants.

And with me, one of the ultimate signs of respect I can give a thrilling yarn is a review of two cold hands. Sounds weird, but bear with me. You see, when I get distressed, my hands become ice cold. You might think I was hypothermic if you touched me. It’s my fight or flight instincts kicking in. It mostly rears its ugly head in extreme situations, but every once in a while it comes up when a narrative has me ill at ease. Typically intense movies or TV shows do the trick, although especially tight NBA or NFL games can have the same impact. Comics? Your typical, pick them up on Wednesday monthly comics? To my knowledge, I’ve almost never experienced that in the form. Most are 20 pages or so and don’t have the depth of experience to resonate in such a way. In fact, only one comic has ever stirred up my emotions to such a degree.

Wild’s End: The Enemy Within #6 by Dan Abnett and I.N.J. Culbard.

It was the concluding chapter of the most recent mini in their series about an alien invasion in a quaint, quiet English countryside town and the ragtag bunch of anthropomorphic characters at the center of it. As I read it, my hands froze as a reaction to the tension of the story and the fear I felt for the characters Abnett and Culbard have developed over two six-issue minis. I desperately didn’t want anything to happen to these characters, but I couldn’t turn back. The story was too good and I needed to see it through.

That just speaks to how exceptional this unique and powerful series is, though. On the surface, Wild’s End could appear to readers as something they’ve experienced a variation of before. It’s Watership Down meets Independence Day or some other alien invasion flick, right? But like with Saga, to boil it down to a pitch is doing it an unkindness. It’s an apt description, sure sure, but it hardly touches on why this book makes you care.

So far, it really is a tale of two stories. The first volume, simply titled Wild’s End, was one kind of invasion story. In invasion parlance, it was Abnett and Culbard establishing a beachhead in our hearts and minds. It delivered our introduction to the the area, situation and core concepts of the series. It’s where we got to know characters like Clive Slipaway, the ostensible hero of the lot; Susan Peardew, the aggrieved author; and my personal favorite, Fawkes, the cunning rogue/town drunk. These first six issues are all about building – building the cast, building the world and building the world. And what a marvelous job they do at that.

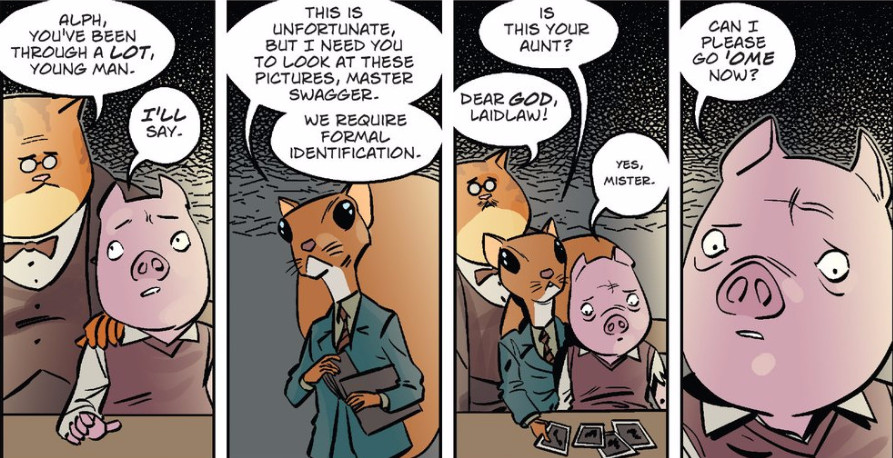

Abnett and Culbard are a stellar pairing, and they prove to be exceptional builders. The area of Lower Crowchurch and Upper Deeping and beyond is filled with characters of true depth and a world of real style. Whether its the formality of language characters like Peter Minks bless others with or the phonetic, cockney accent Fawkes deploys or the dapper and well dressed style the characters are realized in, there’s no angle uncovered. Sure its built on classic sci-fi roots and elements we’ve seen before, but everything from the complexity of our heroes to the exceptional backmatter ensure that this isn’t a hollow tribute. It’s its own fully realized adventure, and one that lay the seeds necessary for a much bigger story.

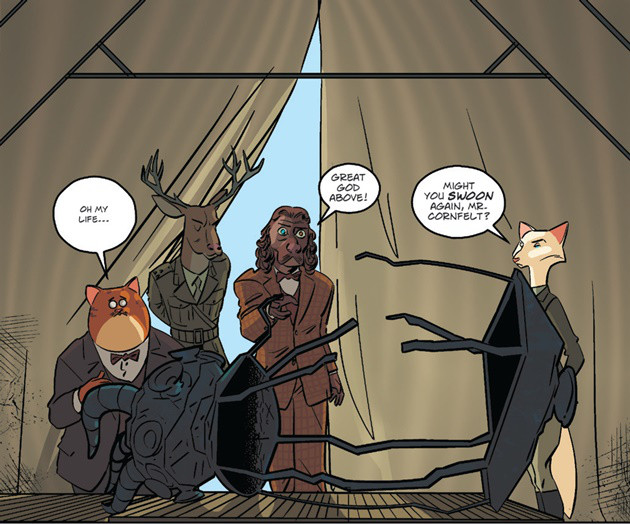

That is delivered in the recently completed follow up mini-series – Wild’s End: The Enemy Within. This second mini found the situation escalating to involve the government while still primarily restricting our perspective to the area we’ve already been familiarized with and characters already introduced or at least mentioned. While there are new characters involved – like the capable and dutiful Colonel Upton and the creepy and paranoid mystery man in charge that is Mr. Laidlaw – Culbard and Abnett built up some of their arrivals in the previous series. The concluding chapter of the first volume’s backmatter had hints to the military’s coming influence, and one new character – science fiction writer Lewis Cornfelt – had been torn asunder in name only by Peardew in the previous volume. Like I said, they’re master builders.

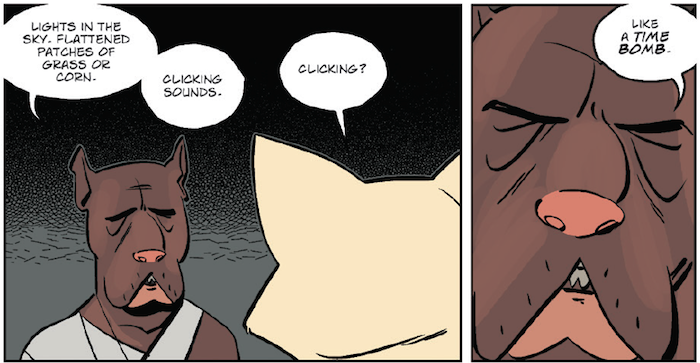

If the first volume was more about establishing the threat of invasion, then the second is more akin to alien stories like John Carpenter’s The Thing. Ones that play deeply off the paranoia created by first contact. Characters like Laidlaw are, in many ways, the real menace for much of the story if only because of his distrustful nature. And like in other tales of that sort, it’s the type of thing that can mask the true threat until its too late. Again, though, like with the first volume, this isn’t a book defined by its influences or the tropes that precede it. It very much is a character first read, and one that delivers nerve-wracking dread by the bucketload.

Take the finale, for example. While I don’t want to delve into any spoilers, that issue works as well as it does because in the previous 11 issues, Abnett and Culbard have established several key things. Those are a) no one is safe, b) no one really appreciates the power of the threat, and c) just because people are paranoid doesn’t mean things aren’t as bad as it seems. It’s a dire, irresistible read, and one that has one of my favorite four page sequences of any comic. That concluding sequence was so brilliant I explained the whole series to my non-comic reader wife after digesting it just so I could show her those final pages (she was less impressed than me, but I’m not the best at explaining things). If a story gets you to excitedly explain it to the uninitiated, that’s how you know it’s working.

Both series are built on the skills of the craftsman behind the books. Culbard’s been featured here for his work on the book already, but I can never overstate what he’s doing here. His ability to animate and visualize the cast is at the very core of the success of the book. Whether its someone like Fawkes or the plump tabby cat science fiction writer Herbert Runciman, Culbard’s exceptionally gifted at making character forms match their storytelling function. To see a character in this book is the first step in understanding them, from the way they stand to how they act.

Even beyond that, his lively cartooning helps soften the story and ease our connections with characters in many ways. As I said before, to see characters is to begin to understand them, and his art is an enormous factor in why we care in the way we do. There’s a visceral quality to his work, and when paired with the disarming qualities of his animation like style, its hard to imagine this story working at all with any other artist, let alone as well as it does.

Culbard doesn’t just draw the book, either. He colors and letters the book as well, and he fills each of those roles with equal aplomb. His colors are particularly effective, as he uses them less as a tool to achieve realism or anything like that, instead using colors to orchestrate our emotions in yet another way. It’s an additional layer that enriches the experience. The whole book is a tour de force visually, and it shows the benefits of a single artist delivering all elements in the interiors.

Worth noting, as well, is the work of the designers on the book. Kara Leopard developed the titling and elements like the little circles that the numbering of the comic inhabits, and its a perfect match for the book as a whole, as is her work on the inside covers (which Jillian Crab handled well in the recent finale).

The language choices Abnett makes have already been mentioned, but its worth bringing up again if only for this reason: these characters aren’t voice boxes for him as a writer. Each has their own linguistic identity, and their chosen dialect of English speaks for each character in much the same way Culbard’s character models and acting does. They’re shortcuts that help us grasp who they are on the go. It’s a simple, natural touch, but something that has weight.

His character work is extraordinary, as well, as he imbues each with so much life and vitality that you can’t help but build a connection to them. The core cast is really what makes this book work, and if even one felt unnatural or like dead weight, the book would be unbalanced by it. Yet no matter the odds, we’re rooting for the cast to not just make it through, but find a solution. The odds are always great, though, as Abnett and Culbard made the threats both brutally effective and surprisingly quiet in the way they go about business (you’ll never hear a klik klak sound again in the same way). Their low impact presence forms a lot of what makes the aliens so threatening. They may be quiet, but the first time you see them tends to be the last time as well.

It’s been brought up already, but the backmatter throughout both series is exceptional. As you may know, backmatter is a draw for me, and what Nik Abnett – Dan’s wife – creates throughout this series adds tremendous depth to Wild’s End. Whether you’re talking the final words of a beloved character in translated letter form (done in such a way because said beloved character “doesn’t know (their) letters”), redacted military documents or excerpts from the science fiction works of the aforementioned authors, its all bonus material that adds richness to the world being built here. Is it essential? Not necessarily. But its impactful for those looking for more from their reading experience.

And frankly, this book is perfect for those who want more from their comic reads. The close of each issue leaves you with an insatiable desire to find out what happens next with the story and these characters. That’s a feeling every storyteller wants to inspire. And as it stands now, I’m not sure when or if the series is going to continue. If I was a betting man, I’d say it will. The close of the second mini could be the end or it could be the beginning, but it’d be a much better lead-in to what comes next. Either that or that’s just the part of me that doesn’t want to let this story go any time soon.

But that’s the power of this brilliant, thoughtful and emotional story, and why its such an evocative read. Wild’s End makes me care in a way that few series ever have. It’s two creators at the peak of their powers masterfully delivering a story of small-town heroes dealing with villains of impossible scale, and despite the insurmountable odds, it never ceases to make us root for their success. For all those reasons and more, Wild’s End isn’t just a good comic; it’s the best comic series on the stands today. And I for one hope what we’ve been served so far is but an appetizer for what’s next, no matter how frigid it might make my hands.

The first volume is available for purchase right this minute, with volume two – The Enemy Within – set to arrive in August.