Cupcakes and Colorists: Kelly Fitzpatrick Talks Her Craft and the Vital Role Colorists Play in Comics

As much as we often talk about the lack of credit pencillers get – and we will even more this week – colorists are hugely vital parts of making the comics we love yet they get even less attention. That’s not for a lack of impact or quality, as we’re in a high time with people like Jordie Bellaire, Dave Stewart, Matt Wilson, Nathan Fairbairn and more at the absolute peak of their game, making the comics they work on better in the process. Their work and a shift in focus has led to an increased amount of attention on their craft, which is a good thing. But there are plenty of colorists who do phenomenal work that deserve their chance in the spotlight.

One of those people is Kelly Fitzpatrick.

She’s the colorist on books like Peter Panzerfaust, Neverboy and Death Head, and she’s gained acclaim already early on in her career. For me, though, the first time I ever saw her work was on Twitter. See, Fitzpatrick had been going around to artists and practicing her craft by coloring their commissions or sketches, and I had seen her frankly fantastic effort on a Back to the Future commission by Sean Murphy. From that point on, I knew she was someone to watch, and she’s just gotten more and more gigs ever since.

Today, you can read my chat with Fitzpatrick as we talk about how she got into comics, the impact those commissions had on her work, the role colorists play in comics, her process and a whole lot more. For those that aren’t entirely sure what a colorist does exactly, this provides great insight into their craft. I thought I knew, but I learned quite a bit from what she shared in the process.

Rather than dipping a toe in as a colorist, you full out jumped into the world of coloring comics in a big fashion over the last few years. What was it that appealed to you about being a colorist, and how did you first start getting into it?

Rather than dipping a toe in as a colorist, you full out jumped into the world of coloring comics in a big fashion over the last few years. What was it that appealed to you about being a colorist, and how did you first start getting into it?

KF: I feel like I dipped my toe in…I started by working as a flatter and then as an assistant for Jordie Bellaire. While I was an assistant, I was still doing flats for a couple other people I had established relationships with at conventions and I worked very briefly doing flats for another colorist. Jordie and Declan helped me meet people online and at conventions and establish a coloring portfolio, which led to me to testing out for Boom and having my first jobs land there.

The second part of that question — what appealed to me? It’s painting! I come from an illustration background and I’ve always been a better painter than line-artist. That’s just how my brain works: shapes than line.

Everyone has a different path to getting into comics, but I’m really curious about how you first got the attention of publishers and creators. For me, I first saw your work on Twitter when you had colored some commissions that Sean Murphy had done, and I imagine I’m not the only one. What do you think has helped you the most in getting jobs and making a career as a colorist?

KF: Yeah! I was asking a lot of people (i.e.: Michael Walsh, Sean Murphy, Cameron Stewart, Tradd Moore, Gabriel Hardman, Chris Samnee, Declan Shalvey) if I could color their work to improve my skills coloring and to develop relationships and a portfolio. Everyone was incredibly nice and sent along AMAZING art! Multiversity and Comic Vine featured some of the pin- ups I colored on their websites too which was really awesome and I think definitely helped me gain exposure. I kept a tumblr (still do!) and updated it with every new pin-up and sequential page I’d color or book I’d work on and I would post the pictures to twitter as well! I of course ok’d everything with the artists before doing so. I’d also ask for critiques from the artists.

I think the tipping point for me getting jobs the most was having the people I colored reach out to other artists. I can honestly trace my short career in comics like a weird timeline of events that led to other events and so on. I think it’s a lot of hard work and persistence, but it’s a lot of right place right time and running with opportunities when they are presented to you. It also involves always meeting your deadlines and sacrificing sleep. Going to conventions I met a lot of people. C2E2 and NYCC in 2013 were the ones that I think affected my career the most. Getting to color Peter Panzerfaust was a big event for me. I was offered the book shortly after starting work for Boom (right after NYCC in 2013). The name of that book carries a lot of weight with it. When I would tell people I was working on it, they were either reading it or recognized the name and it garnered me some clout. The relationships I built with Tyler Jenkins and Kurtis Wiebe were also invaluable. I feel like those guys are brothers to me. It led to me working on an issue of Rat Queens and Neverboy (over at Dark Horse), which led to a lot of other opportunities I honestly can’t believe have happened since.

I really like the story of how your career has come together. It seems – at least to me – that a lot of how you started making contacts came the old fashioned way: by reaching out to people and making things happen. Obviously you’re newer to comics, but if you could go back five years, what would you tell yourself then as advice on how to make this whole comics thing happen?

KF: Unfortunately five years ago, I was stuck thinking I should work making fabric designs for children’s clothing. I had always wanted to work in comics. It’s the reason why I went to design school to get a degree in illustration in the first place, but somehow I got deterred along the way. I wish I could tell myself that I should just passionately invest myself into the 1 thing I wanted to be doing, but I think I honestly needed the time living in Japan (doing a job that wasn’t personally fulfilling to me) to hit that breaking point. I was either going to have the job I wanted or I was going to go on welfare trying. I think everyone sort of ends up digging deep to find the motivation they need to break into the industry and stay in it. It’s like a weird hunger. ha. I know I’ve made it sound dramatic, but I quit a stable job that paid decent without knowing if I could have a career in comics. It was a calculated risk (I had saved up some money) though.

I think some people when they look at colorists, they just think, “oh, they’re the people who make the comics I like not black and white.” While that attitude has subsided in recent years, I don’t the average comic fan knows really what a colorist does exactly and how they impact comics. To you, what is your primary role as not just a colorist but as a storyteller in your own right?

KF: Colorists have a lot of roles in the creative process! To those people who don’t know much about coloring comics and are interested, I would say invest a little energy into doing a google search to see what Nathan Fairbairn has written about on his blog. Nathan’s posted some amazing content about Pax Americana and Nameless and his process (which includes pictures). It’s pretty great! If you are ever at a convention, go to a panel about coloring! My friend and fellow colorist Marissa Louise has been doing a great technical panel about coloring where a whole group of colorists all colored one page! We also talk about where we draw inspiration from, our technical set-ups, the classic RGB versus CMYK argument (CMYK for life, for the record) and answer any questions.

Going back to colorists roles — from a technical standpoint, you can see the differences in color spaces, changes of line color, texture, shadows, highlights, etc. From an emotional standpoint, colorists use color to trick your brain into feeling a certain mood. We all know certain colors evoke emotion (i.e.: red= anger, etc.). Color can also be used to bring focus to certain objects or people in panels (i.e: the girl in the red coat in Schindler’s List). We can also use color to weave a story or to subliminally tell a story about a character. It’s pretty common knowledge that villains and heroes wear certain colors as an example.

At this point, do you flat your own work or do you work with a flatter? Also, for those who aren’t familiar with the concept, what is it that a flatter does?

KF: I do use a flatter and a flatting service! Flatters are AMAZING and make my coloring world go round. They cut down my time spent on a page significantly. I occasionally flat pages myself if I have time or if they are simple, but 95% of the time, my pages are going to my flatters.

A color flatter is someone who works with a finished inked page and fills it with flat color. The flatter selects objects in the page with a lasso or uses the pencil tool and then fills in the area with a solid, flat color. Some artists will be specific with what color palette they want with their flats, but most people I know just get weird colors back (ie: stop signs purple, orange grass, yellow skies, etc.). It’s used as a separating tool for colorists to speed up their work.

You shared a sweet gif of your work in Death Head from Dark Horse Comics that shows a break down of how your work evolves during your coloring process, but can you walk us through what your approach is from beginning to end?

KF: Sure. At the beginning of new books, I read the script and talk to the team and spend most of my day looking at similar work that’s been done before and seeing how I can take what has worked in the past, make it mine, and use it to my advantage and scrap what I don’t like. I normally spend 3-5 hours on a palette for a new project. It’s the hardest thing for me. A normal day is me waking up, drinking coffee and watching tv, while answering emails from the east coast people who’ve got a 3 hour advantage on me. I normally look over my calendar and see how many pages I have set up for the day and grab my pages from my flatters and prepare them to be color corrected (making all of the shapes on the page the correct mid-tone color I’m going to be using before I do shadows and highlights). Then I go in and add shadows, highlights, SFX, etc.

If it’s a complicated book like Veda, I found I had to assembly line (no pun intended) the book to color correct all of the pages on one day (which includes fixing any flatting errors), and then start actually coloring the following days. I would do backgrounds all at one time, then the robots, then color veda, then color the gremlin, etc. down the line until I finished the whole batch of pages at 1 time. That’s normally a bit of an exception unless I am painting backgrounds (like clouds or trees) on multiple pages and I don’t want to switch my brush out. Surely this technical stuff must seem really tedious and boring. ha. Revisions come last and sometimes never. I hear feedback from editorial, the writers and the artists on the book for tweaks or things I missed/need changed.

I’m sure this varies from project to project, but how closely do you work with the line artist on any given book? Does it vary wildly, or do you find that creator-owned you see more communication with them than on books that are for-hire work?

KF: Totally varies. In an ideal world, we’d work closely with each other. Creator-owned through Image and Dark Horse is totally different than working for other companies. Image is driven purely by the creative team with no editorial unless an editor is hired on for the project. It’s also up to the team to do marketing, which I find very stressful. So if you aren’t in touch with each other, the project will fail. I like being very involved with the creative team to the point where I’m pretty sure I got close to annoying Shaun Simon texting him about when Neverboy should have white hair and cyan clothes because he transitions so much back and forth through the series. ha ha. I must have texted him questions at least 10 times it feels like.

Those are the type of projects that I legitimately get sad over when they end. I like having the open communication because I feel more like a team member and less of a freelancer. With that being said I don’t want to discredit the other companies I’ve worked with! And I want to extend a huge kudos to Alex Segura over at Archie. He’s an amazing editor and keeps everyone on the creative in the loop for projects! The communication is pretty open over there too!

You work on quite the mix of books, from occasional jobs at DC on Sensation Comics to creator-owned books to things like the Dark Circle books we’ve already talked about a bit. For you as an artist, though, do you try to focus on jobs that you’re personally interested/invested in? Is that a major factor when you’re considering jobs?

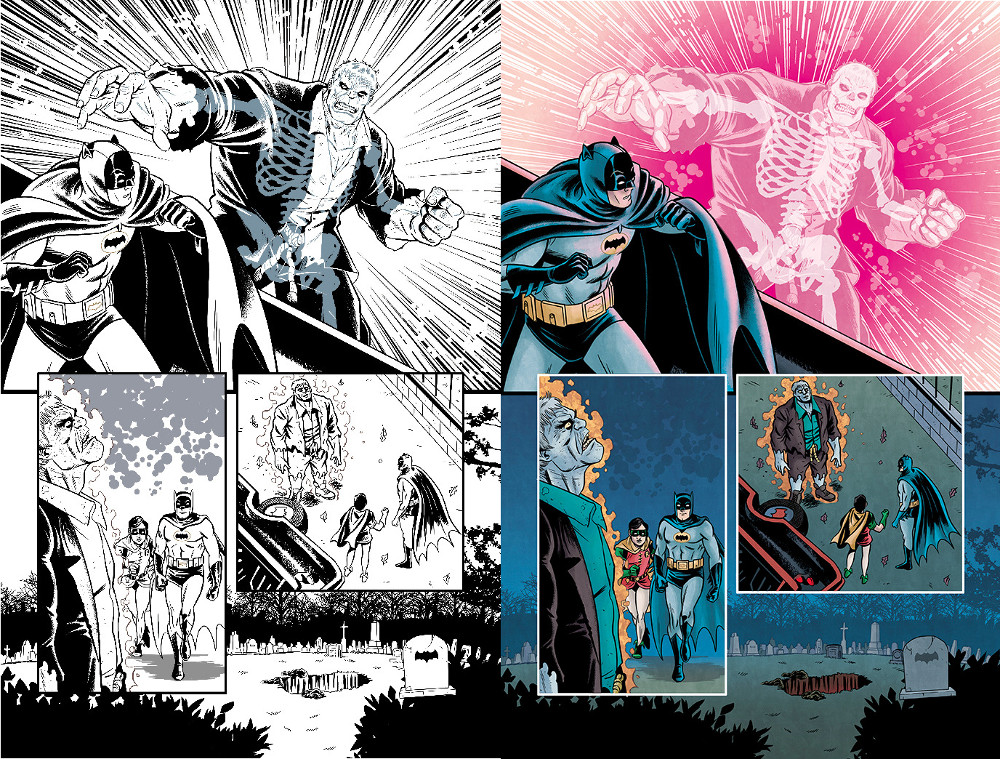

KF: It’s definitely helps factor into what I’m working on sure! I’m still pretty early on in my career in comics though so I have taken on jobs strictly to pay bills, but with that being said, I’ve also worked on jobs for lower pay because I believed in the project and the people I was working with. Ideally I’d like to get to a place in my career where I’m working on projects that are all really really meaningful to me and I feel like that’s been happening. It’s not a matter of creator owned or licensed characters because they can both be fulfilling in different ways. Getting to work on Batman ’66 was a HUGE deal to me. I grew up watching re-runs of that show every day after school! And I already mentioned how crazy fulfilling Neverboy was to me. I was so emotional the day the colors for the final issue were approved. I also really like variety. I know I work on a lot of crime, noir, and horror comics, but I really enjoying working on all- ages and psychedelic content too!

As I said before, to a degree, many fans don’t exactly know what colorists do. What’s the one thing you’d like to see more people consider when they look at colorists and their contributions to the comics we love?

KF: I feel like colorists are the final piece to the puzzle in a creative team and I wish we had more recognition for our profession as a whole. I’d like people to look at the credits page every time they open up a comic and see just how many people are working to create one single issue. We are part of a team and the creative process.

I’ve always described colorists as icing on cupcakes – without us, you’d have a perfectly good muffin, but most people like cupcakes better. :)

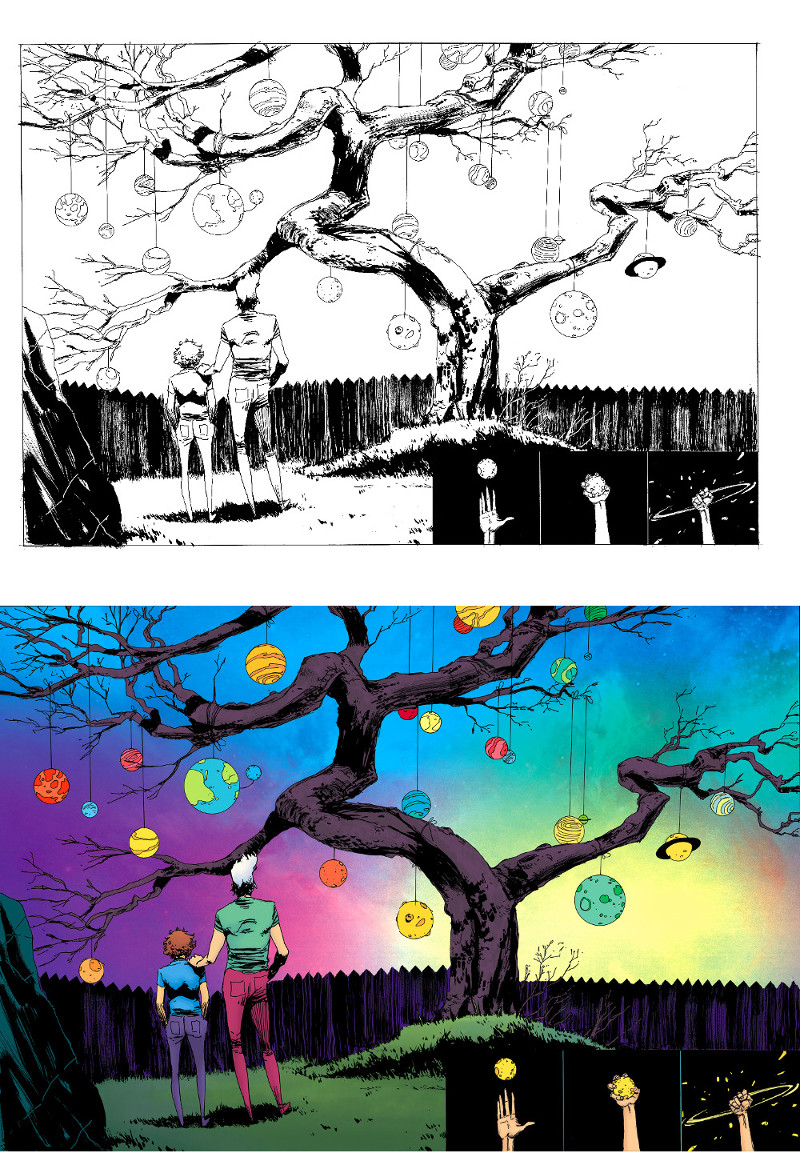

Art from Batman ’66 by Brett Schoonover. Art from Neverboy by Tyler Jenkins. Art from Death Head by Joanna Estep. All colors by Fitzpatrick.