Do Publishers Need to Rethink the Format of Comics?

The growth of graphic novels despite a greater focus on floppies is analyzed

For a relatively large marketplace, the comic industry is a static one. Since their rise into popularity in the 1930’s, the look and feel of comic books has changed very little. The dominant form – monthly floppy releases – has remained the same throughout. While there have been variations—digital comics and trades/graphic novels have risen in popularity—nothing has ever approached the magnitude the pervasive floppy form has achieved for comics.

Or so most think.

When looking around comic book shops or reading articles on the comics internet, one might think floppies aren’t just the dominant form of sequential storytelling in print, but the only one. That couldn’t be further from the truth. In reality, trades and graphic novels already lead floppies in revenue, even if perception hasn’t quite caught up with reality. Not only that, but they’re growing at a faster rate over the past couple years than the floppy market. That’s huge, and a fascinating shift given the industry’s aforementioned focus on its format of choice.

But why is that and where is it coming from? Those are important questions, but perhaps the one most in need of an answer is this: do comic publishers need to rethink their approach when it comes to the format of what it publishes? The answer for me is yes – to a degree – and we’ll explore why by digging into the other questions below.

Note: monthly comics will be referred to as floppies throughout the article while trades, collections and graphic novels will be labeled graphic novels.

Reading the Tea Leaves

If you asked most comic fans or even those who work for most prominent publishers, a large percentage would guess floppies are a larger part of the comic industry’s bottom line than graphic novels. As shared earlier, while that may be the way things are perceived, the reality is different. The revenue of the graphic novel section of comics across all channels is already higher than the floppy market, and by a significant amount. According to numbers shared by John Jackson Miller of Comichron, in 2014 graphic novels generated $460 million in revenue while the floppy market delivered $375 million. The difference is significant – $85 million – and almost a quarter again over what the floppy market was worth in 2014.

There are simple explanations one could use to explain this, of course. With all channels included, we’re not just talking comic shops, but bookstores, book fairs and online vendors like Amazon (it does not include digital or library sales, per Miller). While floppy comics have representation in those other channels, graphic novels have far more. That extended reach contributes to its revenue advantage. If you look exclusively at comic shops, floppies generated almost twice as much revenue as graphic novels, with the former earning $353 million in revenue compared to $177 million for the latter. That’s a big deal, and a large part of the continued dominance of floppies with retailers.

But you know who doesn’t care where revenue is generated as long as they’re generating it? Comic publishers. They’re businesses, after all, and companies of all varieties are looking to generate revenue. If the graphic novel market is expanding to be a more important part of the mix, odds are publishers are already contemplating how they can leverage it. Or at least we hope they are.

It’s not just outdistancing floppies in revenue, though. The graphic novel market is growing, and at an even faster rate than floppies. In the numbers Miller shared, floppies surpassed the growth of graphic novels over the past three years. But much of the growth came in 2012 thanks to surges driven by the New 52, Marvel NOW! and the ascent of books like The Walking Dead and Saga. If you focus on the past two years, though, graphic novels have outgrown floppies by just over 6 percent. Miller explained why:

“The acceleration in graphic novel sales growth has mostly come from the book channel, though graphic novel growth slightly outpaced comics growth in 2014 in the comic shops as well,” he said. “Part of what is going on has to (do) with the inclusion of a lot of titles that for various reasons are not captured by Diamond’s reports; comics retailers ordering directly from Scholastic, for example, would see their sales included under Book Channel.”

“Another factor is that book channel sales were performing relatively more poorly in some recent comparison years — recall the manga implosion — so it was coming off of some smaller numbers comparatively.”

All of those factors are important when considering the context of the market shift. Recent years have seen several important changes, include a rebound from a relative down time for graphic novels in the book market. But the biggest reason might be a single person: Raina Telgemeier.

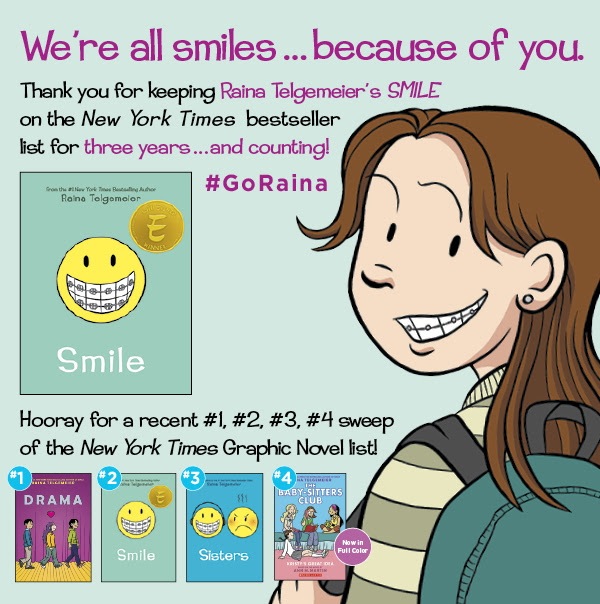

Some comic fans may not even know who she is. Telgemeier creates comics for young readers, and your average Wednesday warrior does not concern themselves with those. But Telgemeier is without a doubt the biggest and most marketable name in the comic industry today. Her most recent book – the autobio graphic novel Sisters – opened with a print run of 200,000 copies. All it has done since its debut in August of 2014 is appear on the New York Times paperback graphic books bestseller list every week alongside her book Smile, which has been on the same list for over three years. Her dominance extends further with books she created recently taking all four of the spots at the top of the bestseller list. That is a feat unto itself.

Some comic fans may not even know who she is. Telgemeier creates comics for young readers, and your average Wednesday warrior does not concern themselves with those. But Telgemeier is without a doubt the biggest and most marketable name in the comic industry today. Her most recent book – the autobio graphic novel Sisters – opened with a print run of 200,000 copies. All it has done since its debut in August of 2014 is appear on the New York Times paperback graphic books bestseller list every week alongside her book Smile, which has been on the same list for over three years. Her dominance extends further with books she created recently taking all four of the spots at the top of the bestseller list. That is a feat unto itself.

While many comic creators are big names and plenty have contributed to this shift, no one has pushed the growth of the graphic novel market more than Telgemeier. With her comics being tallied as part of the book channel, she’s likely a substantial part of the market’s growth on her own. That also explains part of what Miller was saying. With Scholastic selling direct to comic shops, the work by Telgemeier and Scholastic compatriots Jeff Smith and Kazu Kibuishi would be tallied under the book channel rather than comic shops. That is likely a big cause of the disparity between graphic novels and floppies in the comic shop channel.

It’s not just the revenue numbers that are showing a change in the way graphic novels are perceived. Barnes & Noble – one of the largest book chains in the United States – recently announced it was doubling its graphic novel and manga sections due to increasing interest from its customer base. Despite a down quarter, book retailer Books-A-Million saw continued growth in graphic novels. Those results match what we’ve heard elsewhere. As Image’s Eric Stephenson shared in an interview with me, “from all the feedback we’ve received from librarians and bookstores, the biggest growing category is graphic novels.” We’re seeing that in execution.

Amongst the retailers in my recent survey of 25 comic shops around the world, graphic novels rated as the most important segment of their business. In his 2014 in Review piece about his shop’s year, Matthew Klokel – the owner of Fantom Comics in Washington DC – shared that graphic novels have already surpassed floppies as the biggest part of his shop’s sales. He predicted in 2015 graphic novels would eat away even more at the share floppies have. And as he said in the piece, it’s “not because comic sales are declining – quite the opposite, in fact – but because (their) graphic novel sales are increasing at a far greater rate.”

While that is not representative of retail as a whole, it’s interesting how valuable this segment is to some of the most successful retailers in the industry and how it isn’t just bookstores the graphic novel format is thriving in.

The Why Behind the Numbers

So what’s driving the move towards graphic novels? While you can’t pin it entirely on them, much of the growth has been thanks to new and casual readers who are often young women. You can see that in many places, from the hordes of fans at signings for Telgemeier, Smith or Kibuishi to the graphic novel sections of your local bookstore.

You can see it in comments about trends online, including Klokel’s breakdown. He said over 60 percent of sales to women in his shop are for graphic novels compared to just under 50 percent for men. Meanwhile, Patrick Brower of Challengers Comics + Conversation estimated 70 percent of his shop’s sales for all-ages comics were graphic novels, adding, “younger readers seem to be far more interested in graphic novel series than single issue comics.” Certain reader segments have proven to be more interested in graphic novels over floppies as those retailers have experienced first hand.

Christopher Butcher of Toronto Comic Arts Festival and retailer The Beguiling has seen it. He wrote a smart piece – one that helped crystalize my thoughts for this piece – about the growth and developing acceptance of “othered” groups and segments in comics like manga, kids comics and women readers and creators. As he said, “we as an industry have made enormous steps in the last 20 years to not deliberately exclude women and young people from the comics medium, and to actively celebrate their accomplishments. That doesn’t mean that everyone is now suddenly enfranchised, or that the industry is done deliberately excluding audiences (not to mention creators, not to mention people working in the publishing industry), but real progress has been made.”

You can see progress in many different places, but much of the evolution he cited is built on graphic novels. That includes the work of Telgemeier and peers Jillian and Mariko Tamaki, Smith and Emily Carroll. In his piece, he brought up the recent near total eclipse of the paperback graphic books bestseller list by women creators, as they took up 9 of the 10 slots in the chart. That’s huge, and underlines how women readers and creators are bolstering this change.

You can see progress in many different places, but much of the evolution he cited is built on graphic novels. That includes the work of Telgemeier and peers Jillian and Mariko Tamaki, Smith and Emily Carroll. In his piece, he brought up the recent near total eclipse of the paperback graphic books bestseller list by women creators, as they took up 9 of the 10 slots in the chart. That’s huge, and underlines how women readers and creators are bolstering this change.

It’s been such a seismic change that mainstream sources like the New York Times have addressed it in features. The Times highlighted Telgemeier and many others in a look at how the publishing and marketing of comics has shifted away from men. Françoise Mouly – the New Yorker’s art editor and former co-editor of RAW Magazine – talked about the rise of graphic novels and imprints who publish them in the piece, and said, “it does open the path for artists and authors like Ms. Telgemeier, and for publishers to want to do books that girls will read, because each time they’re discovering the obvious: ‘Oh, we’re ignoring half the audience!’” That’s likely a big part of what has driven the growth we’ve seen.

On a micro scale, I’ve seen potential new readers – both women and men – turned off by the floppy format first hand. For example, my nephew is someone who appreciates comics like David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, Craig Thompson’s Blankets and Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim series. Recently, he was at a comic shop looking for something new to pick up and he wanted to know what I would recommend for him. At first, I walked him through floppy based trades such as Lazarus and Deadly Class, but he pushed the conversation in another direction. He was interested in graphic novels or already completed stories in trade form, and the recommendations adjusted accordingly.

That’s something my wife agreed with in a recent interview here on SKTCHD about the All-New All-Different preview book Marvel had released. “The way they come out as a thin floppy every few months or so doesn’t hold my interest,” she said. “To me, it’s like reading a chapter of a book and then waiting a few months to read one more chapter. I enjoy reading a book to have a complete story, even if it is a series.”

She also compared comics to TV, and shared she’s happy binge watching a favorite TV series over Netflix or iTunes knowing another complete story will come eight to ten months after. With floppies? That format doesn’t deliver enough impact to make the month wait worth it for her. If it was a continuing story delivered in yearly graphic novels she would be more into it. I’m certain many new and casual readers – especially those who already trade wait – would agree with that sentiment.

While that is only two people, it matches similar conversations I’ve had with others. In my lifetime, I’ve had just one friend who lived in the same city as me that read comics. The most often cited reason for not being interested in reading them – even friends who would borrow my trades and graphic novels – was a lack of interest in the floppy format.

That’s not to say that new and casual readers are the entire reason for the growth we have seen. Graphic novels have seen a wider breadth of genres tackled and the release list has expanded over the years. With their success increasing, you’re seeing publishers both large and small entering the fray. That means there are more graphic novels and a greater number are well crafted. For comic fans, we have a higher quality to choose from these days, and are a part of the development of graphic novel sales as well.

What Needs to Come Next

To bring back a comparison from earlier, television is arguably the most comparable narrative medium to comics due to its serialized nature. But TV has evolved since its inception, developing past its broadcast foundation into a wide assortment of delivery options that have enhanced the quality and impact of the medium. Would any of us be happy if the focus of television was still on NBC and CBS instead of places like HBO, AMC, Netflix, Hulu and beyond? Not likely. For the same reason, it seems odd that readers and publishers are satisfied with the comic delivery system staying as stagnant as it has for so long.

Despite all of this, I am not anti-floppy. Floppies are far and away the bulk of my comic book purchase list. If that format was abandoned, odds are the amount of comics I read would be reduced by the change. Floppies are a huge part of the marketplace, and for trade paperbacks in creator-owned comics – books like Saga and The Wicked + The Divine – they generate the cash flow writers and artists need to ensure they make it to trade, Rocket Girl’s Brandon Montclare shared in a previous article. Once a creator-owned title releases its first trade, they can prove to be a large part of the revenues those books take in, as WicDiv’s Kieron Gillen wrote in June. They are both important parts of the mix for creators and publishers.

They are both important parts of the mix for creators and publishers.

But in a marketplace that is growing and changing, why not rethink how we publish comics? Why not try and see if there is a way we can stoke the flames of interest in potential new readers by taking a different angle on the format? While publishers like First Second, Drawn & Quarterly, Fantagraphics and more have long hanged their hat on graphic novels and reaped the rewards from the growth that format has seen in recent years, many major publishers still treat trades and graphic novels like the publishers are the Dursley’s and graphic novels are Harry Potter. They belong under the stairs with our underage wizards and filled longboxes.

The trade release strategy of many direct market centric companies confuses as much as it does anything else. Marvel in particular perplexes. Its biggest titles’ graphic novel releases do not arrive anywhere close to their arc’s end. Take Avengers Volume 5: Adapt or Die as an example. Marvel released a high-priced hardcover – five issues for $24.99 – three months after the final issue of the book’s arc, and the trade paperback dropped eight months after. That is almost a year from the close of a story to being published as a trade paperback. Why wouldn’t a reader just pay $9.99 a month to read the same story – and many others – on Marvel Unlimited at that point?

Another trade release that befuddled me was the first volume of Lumberjanes from Boom!, a book whose debut was the top selling single issue at both Klokel and Brower’s shops in 2014. For a title aimed at young women readers, you would think releasing a trade would have been a priority to capitalize on the interest in the book. Yet nine months passed between the close of the last issue included in the first volume and the release of the trade. I’ve heard both readers and retailers lament how that played out, but it is worth noting how it worked out in the long run: its first volume is already in its fifth printing.

The only floppy publisher who seems to be actively leveraging this side of the business is Image Comics. Their trades are often released within two months of the close of their most recent arc. Most of their titles have embraced the popular schedule Saga uses—an arc comes out in issue form, the next month there’s either a break or the trade drops, another break comes depending on the book, rinse, repeat—and that seems to be growing in adoption.

In addition to that method, they recently announced a graphic novel aimed at younger readers in Steven T. Seagle and Jason Katzenstein’s Camp Midnight, which pairs well with that market. They are also publishing books in outside-the-box sizes and shapes like Brandon Graham and Emma Rios’s Island Magazine, an anthology series that falls somewhere in-between a floppy and a trade. While those are only two examples, Image appears to be willing to experiment with the format of the books it publishes. That’s great, and leaves me wondering why more publishers don’t do that.

Beyond that, why aren’t publishers like Marvel and DC using their enormous movie revenues – which admittedly come from a different segment of their businesses – to create a graphic novel line related to its movies readers can jump into without previous knowledge? Why doesn’t Marvel create an Ultimate like universe built around semi-annual graphic novel releases aimed at new and casual readers? Why aren’t more comics collected in the aggressively priced digest format manga has thrived in? Why are so few direct market publishers buying into the way the winds are pointing in comics?

I promised to answer questions, and while I have, I’ve left you with even more than we started with. That underlines how important this topic is. The graphic novel side of the business – like digital – has proven to be additive so far. It can exist in a greater form alongside floppies. But much of the industry doesn’t exhibit an interest in doing that.

This piece isn’t saying the floppy comic format should be abandoned. Far from it, in reality. What I am saying is if we’ve learned anything in recent years, it’s that approaching comics in a different way can lead to major rewards. At a certain point, doing something because it’s the way we’ve always done it just doesn’t suffice any more. If we want the comic industry to reach the heights we all want it to, embracing a new way of doing things may be necessary despite how much we want to hold on.

Art in the piece by – in order from top to bottom – Raina Telgemeier, Jillian Tamaki and Jamie McKelvie/Matt Wilson. All trades in the header are mine, and no, you cannot have my glorious skills at spreading them out for an image. Hat tip to former Multiversity cohort Mark Tweedale for the idea on the broadcast/streaming TV comparison.