The Long, Winding Road to Echolands

J.H. Williams III and W. Haden Blackman take us behind the scenes of their new Image Comics series.

Sometimes we, the people who engage with varying forms of entertainment, behave as if these things we love or hate or feel nothing for are willed into existence in the very moment we take them in. “This story has to be a reaction this” or “that movie obviously felt the influence of that,” we think or say or tweet. But the reality is, as much as it may seem that way, that’s often not the case. The path from ideation to the actual release of a finished product can be a long and winding road, no matter if said finished product is a book, film, TV show, or, most relevantly to us, a comic book.

In the case of the latter, it can take considerably longer than most comic fans realize, even if we believe we already know how time-consuming comic creation can be.

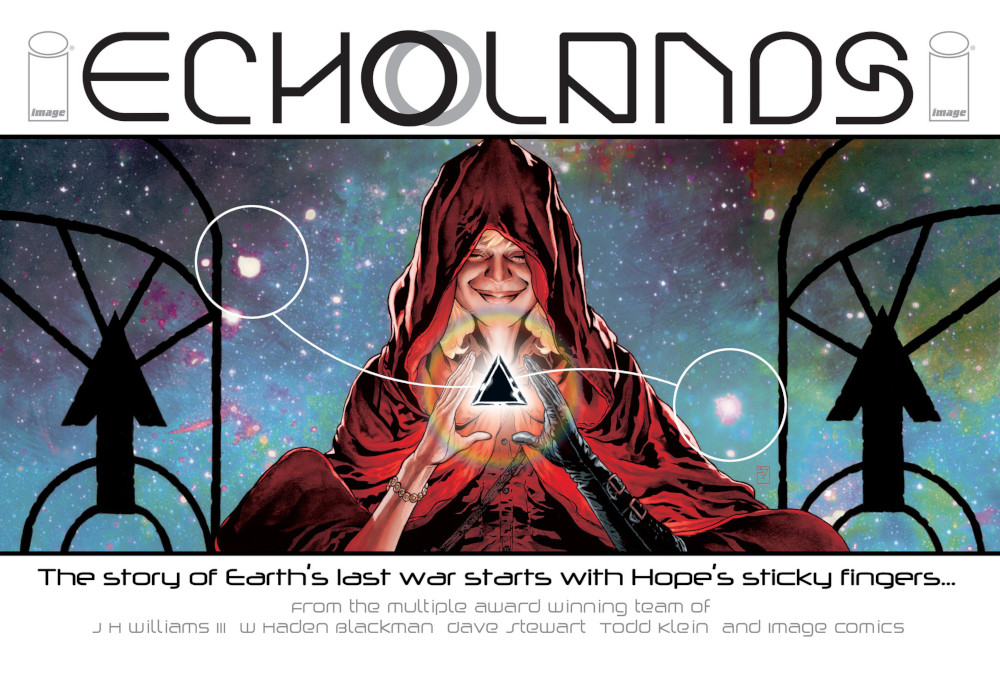

Take Echolands, J.H. Williams III, W. Haden Blackman, Dave Stewart and Todd Klein’s Image Comics series that launches this week, as an example. This unique, landscape-oriented series that tells the tale of Earth’s last war and the thief who sets us on a path to that crescendo was announced back in February 2018 at Image Expo, the publisher’s occasional event designed to roll out its next wave of releases. Fans remember this, if only because it was long enough ago that it made many wonder if it would be another project from those events that simply never came to be, a fleeting idea that excited for a time but disappeared just as quickly.

It didn’t start there for Blackman, though. His journey to Echolands began 15 years ago in a phone conversation with Williams, as the two batted around ideas for a potential collaboration in the relatively early days of the former’s comics career.

And for Williams, Echolands is almost the story of his life, as a vision of series lead Hope Redhood, her nemesis Teros Demond, and its world has existed in his mind and sketchbook since he was a youth.

What arrives tomorrow in Echolands #1 is a rare treat: a title that I can truly say is unlike any other comic I’ve ever read, in the very best of ways. And for it to become such a unique experience, it needed to cook for a while – a long while – with time being an essential ingredient in its path from an aspiring artist’s vision to a singular entry that brings the very best out of its A-list creative team. Today, we’re going to explore Echolands‘ journey from idea to released comic, as the two head chefs behind it reveal how this dream became a reality.

Echolands begins with a story of hope.

Actually, let’s start that again.

Echolands begins with the story of Hope. While this character, the protagonist of the entire tale, isn’t everything to its origin story, it was the part that Williams was most sure of from the jump. Even back in his youth, she was visually complete in his mind, acting as the spark that lit the fire of this eventual release.

“The character came to me fully realized in a lot of ways. I knew what I wanted her to be like and what she looked like all the way down to many of the physical features she has,” Williams told me. “Even in her clothing were things I thought of way back when I was a kid.”

But even then, it wasn’t just Hope. The youthful version of this renowned artist knew that the land she resided in would be “full of turmoil” compared to ours 1 and that “she had a wide range of adversaries and allies” to populate this land. While each character has morphed considerably since then, 2 Williams had sketches of other core characters back then. Some elements of the story were very much the ideas of a young person, with the title’s villain Teros Demond being depicted in a way the artist described as “naïve and stereotypical.” 3 It still felt real, though.

But it needed more.

That’s where Blackman comes in. The writer was a relative newcomer to the field when the pair first began discussing the project, having only tackled a few projects related to his work at LucasArts. 4 The duo met for the first time at San Diego Comic Con through colorist Alex Sinclair, quickly hitting it off through their mutual admiration of certain horror movies, albums, and, of course, comics. They became fast friends. And around the time Williams was working on Promethea, the two hopped on the phone, with their path to this project beginning there.

“We were just shooting ideas around (when) he said, ‘Hey, it’d be great if we could maybe do something together,’” Blackman said. “He told me at that time, ‘I have this vision from when I was a kid of this woman, Hope Redhood.’”

The guts of the story were already there. Williams laid out core story beats from the first issue on that first phone call. And Blackman was into it from the start, with two main ideas hooking him. First, he loves how it’s Hope’s impetuousness that launches this giant story, as everything begins when this young thief steals a powerful jewel from Demond without even knowing its true power.

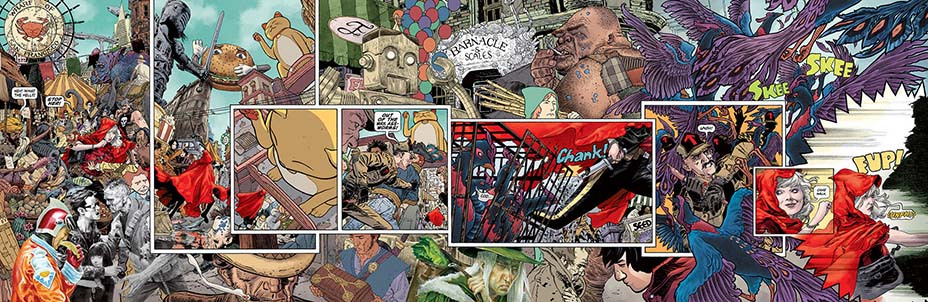

Second is the secret sauce to the world that neither creator would reveal to me. Whatever it is, it’s what allows the series to be such a unique “genre mashup,” as Blackman put it. Our first introduction to the world in issue #1 finds characters from a wide variety of stories, each drawn by Williams and colored by Stewart in different styles to match their points of origin. As someone who has kept a list of all the things he loves the most in this world since he was 15 – with said list including ideas like zombies, robots, vampires, werewolves, and cowboys, many of which can be found in Echolands – this was deeply appealing to Blackman. All of that stems from this second hook he alluded to. One way or another, though, he was in.

Up until this point, the world and its ideas lived solely within Williams’ head. As he told me, that’s where most of the stories he works on reside until he draws them. He had sketches from his youth, of course, but nothing formalized. What he needed was an able partner to bring it all to life. He found that in Blackman, who quickly dived into the idea with him.

“A lot of it ended up just being conversations on the phone about things I could see in my head and things he could see in his head,” Williams shared. “So, it became this kind of synthesis of both of our perspectives and attitudes and ways of telling a story and interests.”

Once Blackman entered the picture, these ideas and characters began to transform into what appears in Echolands. The pair spent a lot of time chatting on the phone in those early days, figuring out details of the world and where it needed to go. Unlike Williams, Blackman is a man of structure, and he shared that they put together a “detailed pitch and overview” as well as an “issue-by-issue breakdown” to help path everything out. They had big plans, even if it all began with a vision of a single character.

“I wanted to do a world bible and build out a world because I feel like we can create (something) that suggests thousands of stories,” Blackman said. “That’s always going to be more engaging and enriching then if it’s all just based on Hope’s story alone.”

Between that fateful phone call and Echolands’ announcement at Image Expo, a whole lot of development was taking place in the background of all the work each creator was doing. The project was even garnering interest amongst publishers. But then, as Blackman told me, “Other things just came up.”

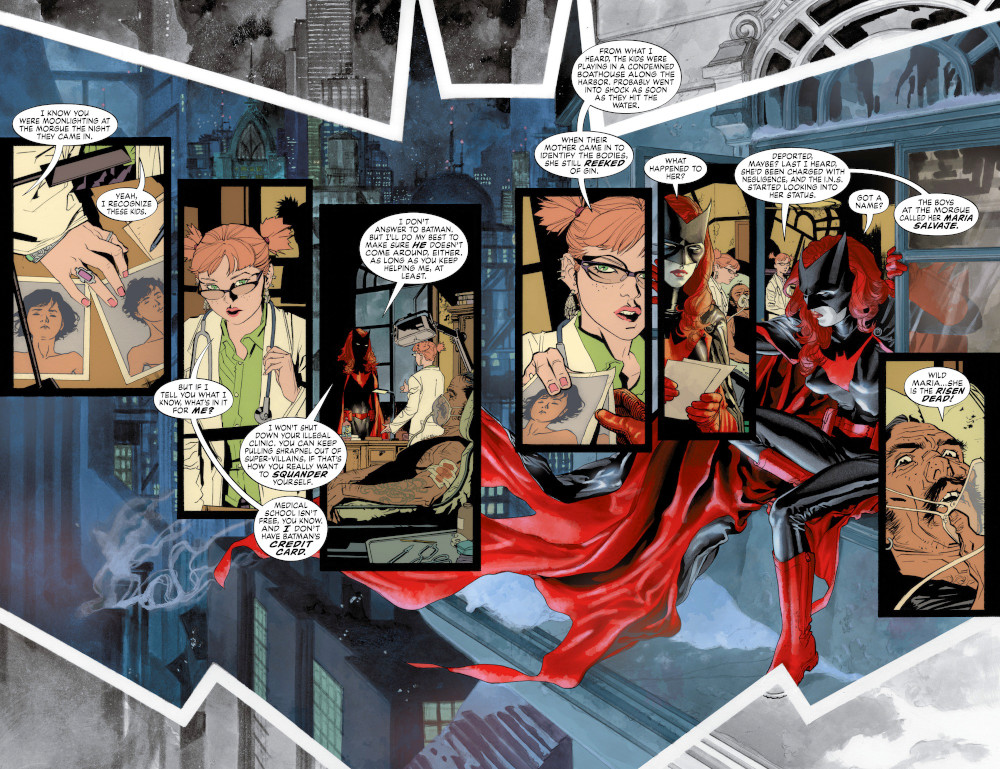

First was the launch of their Batwoman title at DC. Per Blackman, Williams was protective of Kate Kane and her story, so when they were offered the chance to follow up the artist’s run with writer Greg Rucka in Detective Comics, they went for it, even if he described it as a “really hard decision” at the time. They had “fleshed out the first couple arcs” and were “getting some traction” on Echolands. They just couldn’t pass up a chance at Batwoman.

Both creators were thankful for the opportunity. Williams described it as a “boon,” as it was a trial run for actually making a comic together. He said their time on that project probably made “our work on Echolands stronger because we had that opportunity to grow.” Not only that, but according to Blackman, collaborating with Stewart and Klein on Batwoman allowed them to pitch the pair on Echolands. In a way, it was when the full team was officially formed, even if it was still long before its actual release.

Williams was offered Sandman Overture shortly thereafter, and while it too was debated as they were effectively in agreement with Image for Echolands at the time, Blackman insisted the artist take the project.

“I was like, ‘You have to do it because look at who you’ve worked with. You worked with (Grant) Morrison. You’ve worked with Alan Moore. And now, you get to add Neil Gaiman to that list. Think of all you’re going to learn just working with Neil. So, go do it. And then, maybe I can learn from osmosis.’”

Even Image was supportive of the move. Everyone agreed that attaching yourself to the runaway train of popularity that is Sandman is an effective way to increase the sales potential of your future projects. And Blackman was busy too, as he was putting together the video game Mafia III at his day job, a not inconsiderable project on its own. Throughout all those other efforts, though, Echolands “was always percolating in the background,” growing and evolving.

I was at that Image Expo event in 2018 when Echolands was announced, and I remember thinking it was interesting that it was one of the few projects that didn’t have a set date as part of the reveal. They didn’t have a firm date at that point, but they went in with intent to make it happen sooner rather than later. They even had a lot of solid work done by that point, although how much depends on who you ask, as Blackman suggested they were “already done with two or three issues” while Williams insisted he didn’t “think (he) was that far along” by then.

So, what caused the project to take as long as it was, with three and a half years passing between announcement and the arrival of its first issue? In short, life. To elaborate on that, though, it was a mix of factors. Blackman said an early one came from writer Rick Remender, 5 who suggested at Image Expo that they should get as far ahead as possible before launch to ensure readers have a satisfying experience. They endeavored to follow that advice, aiming to complete at least the first arc before the series debuted.

There was also Where We Live, an anthology conceived by Williams and his wife Wendy Wright-Williams that was born from the mass shooting in their hometown of Las Vegas on October 1, 2017. The pair spearheaded the projected, with Williams spending countless hours gathering A-list writers and artists for this book that was designed to benefit survivors of mass gun violence via the nonprofit Route91Strong. It was a worthy cause, but those hours had to come from somewhere. And they came from Echolands.

One other key part of this story is talked about less, and that’s because it involves Williams’ personal health. During this period, the artist “ended up with appendicitis,” resulting in emergency surgery and, immediately afterwards, sepsis. It was an extremely difficult time for Williams. His memory of the period is foggy, with his wife saying it was at least eight months before he seemed remotely like himself. For a long stretch, even a simple act like walking up the stairs of his home required assistance, as well as rest afterwards to recover from it. As much as the story of Hope carried on in his head and heart, his body struggled to live up to the demands of his drawing board.

And, oh yeah, that whole pandemic thing came up. As Blackman told me, “It’s not like COVID changed the way we work,” as Williams already worked from home. But it did make them question when the right time to launch was, because who knew whether there would be an audience waiting for it because all the surrounding uncertainty. Without the pandemic, Blackman suggested it likely would have launched sooner. But in a weird way, it too proved to be a boon, as it allowed them “to get a first arc that” they were “really happy with.”

Each of those events and experiences and projects changed them and Echolands itself. The title was in development throughout the turmoil, but their experiences and the work they were doing morphed it in ways both subtle and significant. As Blackman said, while the roots are the same, “the size of the tree and the color of the blossoms have changed.”

Much of that stems from the process of actually doing the work and getting to know their own cast. Take a character named Rabbit as an example. He shows up visually at the end of the first issue before actually speaking in the second. The team didn’t really have grand aspirations for him past that. But when they got to writing, they “fell in love with the character” and made him a much bigger part of the story.

Both creators told me the biggest difference from their pitch document to today is that the supporting cast has both grown and become more important than they originally envisioned. “The actual plot itself and the backstory for the world hasn’t changed,” Blackman shared, but the importance of some characters within it did. That’s the difference between talking about the project and actually making it. The pair gained a lot from spending hours and hours on the phone going back and forth on ideas, and doing the same in shared documents Blackman would create for each issue. But sometimes, ideas or characters just pop.

And then they become something more.

Even Hope herself, a character who has existed in Williams’ mind’s eye for decades, has evolved over the process. As Blackman told me, “Until we started writing her, her voice didn’t exist.” They had to give her an identity beyond the basics Williams had long ago established, and it created a situation where even they were astonished by how much and how quickly she grows on the page.

In some ways, their creative process on the book isn’t altogether different from their version of San Francisco. In issue #1, Hope and her sidekick of a sort Cor are escaping the authorities when they go around a corner in the city. All of a sudden, a wall that had never been there before stops them in their tracks. The city is always changing as its denizens engage with it, constantly surprising even those who know it best.

That’s the case for the book too. It keeps evolving the deeper the pair gets into it. Fittingly, even that very idea – the one of the city itself changing from time to time – came from a question they had about why these two thieves would run into a dead end within a neighborhood they know as well as anything. Blackman and Williams are constantly figuring out solutions on the fly, and more often than not, they do so together. It’s a perfect partnership in that way, Blackman told me.

“Other than the very first conversation, I don’t know which of us came up with some of these characters. I don’t know which of us added this detail or whatever which is good,” Blackman said. “That’s what you want.

“You want that collaboration.”

In a weird way, the cast of Echolands aren’t the only characters. To use a cliché idea, it’s clear even from the first issue that its world is a main character unto itself, maybe even on par with Hope. Part of that stems from the secret hook that Blackman alluded to earlier, as “the origin of the world came before the idea” of using multiple styles. While what that is has yet to be revealed, it allows the pair to fuse a wide range of ideas, “but in a cohesive way that ultimately makes sense,” as Blackman told me. It’s all set up for a reveal the duo believes will blow people away, even if it’s all been there since the beginning.

“Our hope is that people are going to be enjoying the world because of that craziness where you can have a cowboy standing next to a vampire (who is) standing next to a cyborg elf. People are going to go, ‘That’s insane. That’s crazy. But why?’” Williams said. “And then when we reveal how, I know people are going to go, ‘Get the fuck out.’”

They’re building the world up in a variety of ways. A fun one is through the backmatter of the title, a varied mix that includes in-world materials and even musical playlists that fueled Williams through the process. My favorite in-world element is an interview between a journalist named Alias-5 and the wizard Teros Demond, a recurring, illuminating bit of text-based storytelling in the opening arc in which Blackman plays the role of the journalist and Williams stands in for the wizard. Elements like that or even in-world ads and comic strips give life to Echolands without taking away from the story.

Another is via specific art choices, like in how Williams depicts Horror Hill, a locale within the title. Its inspirations were the old Universal Monster movies and 1970s black and white horror comics. To better fit that vibe, Horror Hill is completely black-and-white, fully rendered images, save for the characters who aren’t from that neighborhood. 6 That’s because for Echolands, style is storytelling, resulting in a comic that’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen, fusing endless looks together in a way that completely makes sense.

Pair that with the world-building that’s crucial to the work – everything Williams includes in these locations must match the aesthetic and history connected to it – and you have a comic that takes “an insane amount of time” to draw. Some of it has resulted in unexpected gains. The arduous nature of drawing the Horror Hill section led to the team splitting that part up over multiple issues, a practical decision that helped improve the pacing of the story itself in the process. But the blending of styles and the intimate relationship between the choices Williams is making on the page creates a situation where the artist has to always focus on who he is drawing in the moment to a greater degree than ever before. And it’s not just with the wildly different looks he gives groups of characters; even the core cast is depicted in subtly different ways, despite having seemingly very similar styles.

“When you look at Hope next to (Cor), you can see stylistic differences between them, but they’re less overt,” Williams said. “When you look closely, Hope’s rendering is a slightly cleaner line with actual wash rendering to some of the shadows where Cor has no washes hardly at all and uses a rougher line. And then when Dave colors him uses kind of scratchier blocks of color versus the way he colors Hope.

“But because they’re both rich in color, they feel a little bit more associated.”

These kinds of elements make the comic look genuinely unbelievable, a feast for the eyes in a way few comics are. The first pages set in San Francisco, for example, are filled with so much depth you can spend an endless stretch drinking in the details, observing the decisions Williams and Stewart made on the page. And what a page it is! Maybe the most unique aspect of the title is its landscape orientation, as the comic is bound on the short side of the comic, flipping open from there.

The idea of giving the series a horizontal look was in the initial pitch documents they had sent to Image, and it was something they always wanted to do, both to be different and because it better fit the way they wanted to tell the story. I described it to the pair as something that, bizarrely, makes the comic feel longer and shorter at the same time, and they completely understood what I meant. I’m sure you will too.

It makes the comic stand out. As Williams noted, he’s well-known for his love of double page spreads, and this format allows for Echolands to effectively be made entirely of those. 7 It gives a completely different energy to the read, existing as something that’s both challenging and exciting.

That’s the case for the team too. Blackman said there are things he has to think of completely differently, both from a pacing and scripting standpoint. He shared that an important consideration was making sure the paper stock and cover worked both vertically and horizontally, in case comic shops decided to stand it up vertically like other comics. Meanwhile, Williams expected the idea to be “a piece of cake” once they got down to it. “’It’s no problem because it’s the same dimension. It’s just turning it sideways,’” Williams remembered thinking.

“I was really wrong. It was very quickly challenging and intimidating. And it actually has affected the way we construct scenes in the scripts now.”

They’ve gotten used to it, with Williams saying he’s “starting to think more naturally in a landscape than ever before.” The pair both noted it’s offered them endless opportunities for unique storytelling approaches. 8 That’s a win for them, and for readers.

If that all sounds like a ton to put together, you’re right.

It’s an awful lot of work to do all of this. The good news is, by the time the first issue arrives tomorrow, the team will be working on issue #8. In that span of time, “a lot of life has happened,” as Blackman said. But the pair is thrilled about the book finally being revealed and Hope’s story beginning for readers. It could be a lot more than just that, though.

While there’s a “beginning, middle and end” for what they call “Hope’s Crucible,” the main story of Echolands, the way they’ve set it up could spiral in many different directions. As I noted, its world itself is a main character, but perhaps a better way to describe it would be as the constant of the title. Hope’s story itself is finite, but Echolands is potentially infinite, relatively speaking. There’s the chance for spin-offs and an expansion of the universe – if the title’s success warrants it. 9 And even if it doesn’t, there’s plenty more to come.

That means a lot more work, but they’re excited to take it on. It’s clear it’s been a deeply rewarding experience, and one they’re thrilled to be diving into in full, even if it’s been equally challenging and complex. Much of its intensity comes from Echolands being their own baby, as they’re putting a lot of weight on themselves to do it right. Williams was genuinely astonished by how time-consuming it’s been.

Not just art-wise, either. Each and every aspect of the creator-owned experience has been a lot. There’s a reason creator-owned comics are often described as being similar to running your own small business. That’s almost as difficult to get used to as the unusual format they’re using. This is why, as I said earlier, time has been an essential ingredient in the story of Echolands. It’s taken lots of it to get to where they are.

If the first issue is any proof, the path may have been long, but it was a necessary one. It’s a heck of an achievement that could be overwhelming for some, but for those who are enamored with comic craft of the highest order and top-notch creators going all out, you’re going to find a lot to love. And the journey helped make the title what it is, turning what could have been a fun idea into a far more evocative one. Like Williams told me, it needed all that time, as it allowed Echolands to become “richer and more complex because of our experiences since then.” Blackman agreed entirely.

“I don’t know if either of us, the Jim or the Haden, that first started talking about the idea 15 years ago could have done what we’re doing now,” Blackman told me. “We’ve learned so much in the intervening years. But the fact that Jim can, in a single panel, jump from one style to another is remarkable.

“So, I think the wait was worth it.”

Thanks for reading this feature on the making of Echolands. If you enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more content just like this.

Not quite apocalyptic, though, the cartoonist was careful to note.↩

Save for Hope, who looks the same as he originally imagined her.↩

Eventually, Williams inverted expectations for this grand villain, delivering a version of the character that was perhaps not what readers might typically envision.↩

Blackman’s primary job was and is in the video games field.↩

Or so Blackman recalls.↩

I suggested to Williams that Stewart probably loved that part. He agreed with a laugh.↩

The artist told me that Stewart said the book reads so wide each pair of pages actually feels like four pages, not two. I definitely can see that.↩

Blackman mentioned a future issue in which the story is told in a circle, which almost melted my brain when he described it.↩

I’ve been thinking about it like Hellboy, where there was a main story, but there’s also room for endless stories on the periphery, with the constants being Hellboy and Mike Mignola. That’s the case here except Hellboy is replaced by the world itself.↩