On Panel: Al Ewing and Ram V on the Inner Workings of Venom and Superhero Storytelling

Yo everybody, welcome to On Panel.

Wait…what?

That’s right. On Panel, not Off Panel. While my interview podcast is still going, I’ve long considered introducing a semi-regular conversation series to SKTCHD as a partner to Off Panel. What it would be was a mystery to a degree, as I didn’t just want to do a typical interview. It had to be a different. That’s where the idea and name of On Panel comes in.

On Panel is a text-only sister series to Off Panel, in which each interview features two or more guests as I attempt to simulate the idea of a panel conversation from a conversation. By that I mean it’s a moderator – myself – guiding a free-flowing conversation between multiple panelists about a subject that unites them. It’s meant to be less of a traditional interview and more of a back-and-forth between myself and the guests or the guests themselves, as we talk about a central premise while discussing connected ideas in the process. The hope is this concept will offer some real versatility, as it doesn’t always have to be oriented around a shared comic, spinning out to examine concepts, genres, and beyond. Each month (the plan is for it to be monthly), it’ll be an entirely different animal.

And the first edition of On Panel is a doozy, as I was joined by writers Al Ewing and Ram V to talk about co-writing the current volume of Venom – which is over at Marvel with the exemplary art team of Bryan Hitch, Andrew Currie, Alex Sinclair, and Clayton Cowles – and their perspectives on writing superheroes and existing within universal structures. Ewing and V are two of the finest at finding unexpected but potent approaches to the genre, and we explored the approaches that help them get there.

It was a lengthy chat over Zoom, touching on everything from the origins of that Venom series and the inner workings of how they collaborate to their views on continuity and how to best leverage the shared universe model. Even if you aren’t reading Venom, you’ll find a lot to enjoy in this chat, as Al and Ram are two of the best writers in the business today — and entertaining interviews to boot. We do cover some ground from the first six issues of this volume of Venom, so beware light spoilers if you’re concerned about those.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Additionally, as the first edition of this new interview feature, it’s open to non-subscribers. If you enjoy this feature, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more features like this. Your subscription both gets you access to all of those and more, but supports the work in the process. Which, I can promise you, is a lot!

Venom is not just you writing, Al, and it’s not just you writing, Ram. It’s both of you. How did you two taking on Venom come to be? Were you both offered it at the same time, or did one of you get offered it first?

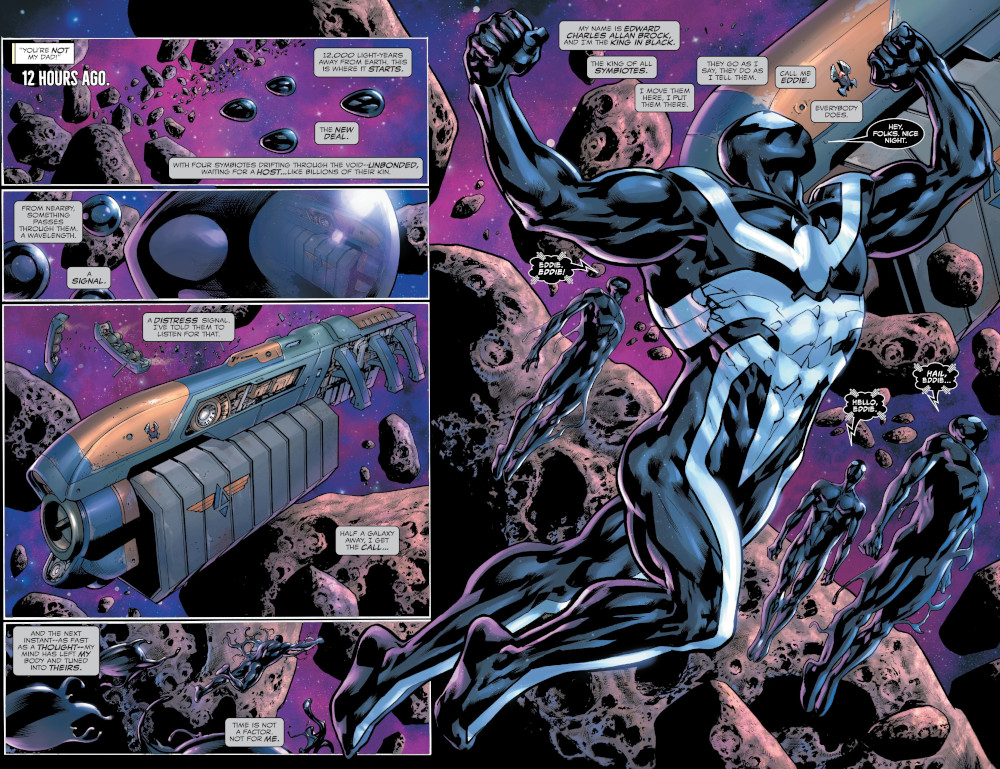

Al: I think it started with me in that I was in the writer’s room when Donny (Cates, the preceding writer of Venom) pitched us on how he was going to end his run, what he was going to end with, what toys he was going to put back in the toy box, and what he was going to leave out for other people to work with, if they wanted to. He ended up with Eddie as this godlike being. It’s a great ending for him, but I was just mulling it over as a starting point. How would that be as the start of a new series?

I was really thinking about that. But at the same time, (I realized), “This is just an Eddie idea.” An Eddie idea does not make a Venom book. People were asking me about it, but I was saying, “I’m not really that interested because I’ve got this big Eddie idea, but nothing else.” At which point, Ram, I think that was when Devin (Lewis, Venom’s Editor) reached out to you?

Ram: Strangely, it was Donny who reached out to me first, but that was a while back.

Al: Oh, there we go.

Ram: That was a while before he had written the end of his run.

When was this, roughly speaking?

Al: It would’ve been about a year before the book hit the shelves, I think.

Ram: This would’ve been around maybe halfway after that. So, Donny first reached out to me and said, “Hey, I’m looking at tying up my run, and there’s some discussion on what to do with the Venom book and I was wondering if you’d be interested at all.” I was kind of in a similar place. I was like, “I don’t really have a huge history with the character, so I’m not quite sure. But it sounds interesting depending on what we get to do with it.”

And so, he said, “Okay, I’ll go talk to my editor and then we’ll come back.” I didn’t hear about it until Devin got back in touch and said, “Hey, so we’ve got this thing. Al’s going to be writing Eddie Brock and he’s going to be doing this huge cosmic space thing, but we also feel like there’s a need for a grounded Venom narrative that is part of that.” Devin actually pitched me the idea of doing this tandem narrative book. And at that point it was super interesting because I was going to get to work with Al, and that had always been part of what I found exciting about it.

And then also, this idea of executing a tandem narrative on a monthly format at one of the big superhero publishers with a well-known character, I don’t think it’s been done. I don’t think it’s been done where there have been two narratives twining with each other, pushing and pulling in quite the same way.

Al: Not like this. I don’t think it’s ever been done like this. I’m not sure which of us Devin would’ve talked to first, but while he was saying, “Are you sure you don’t want to do this?” he dropped Ram’s name as a co-writer or a potential co-writer, at which point I perked up and I was like, “Oh, really? Okay. Now I’m interested.”

It’s this mutual thing of wanting to work with each other. It’s come out real good. I feel like we’ve seeded each other’s stuff.

Ram: And it’s interesting where the stuff that is set up in one story gets paid off in the other narrative.

Al: Yeah, we’re really starting to do that now. The script we’re turning in at the moment, we’re really starting to do that.

I love the part in issue five where you find out that it was Meridius who was inside Ringo in the first issue.

Al: Yeah.

Ram, I’m with you. I don’t know where you stand on this, Al, but I previously had very little affinity for Venom as a character. I oddly liked the first Tom Hardy movie because it’s insane. (laughs) But besides that, I’ve never really been a giant fan of the character. But there was something about the way both the Free Comic Book Day issue and first issue set up promises. Why was Ringo doing this? Why was this Eddie blown up? Most of the time when I think of co-writing at Marvel, it’s working together on one script. And instead, it almost seems like there could be a call and response with this method where maybe Al, you set something up and Ram, you pay it off. Or Ram, you set something up and Al, you pay it off.

I’ve seen you two compare it to being in a band where every trade is an album, every issue is an individual song, and Eddie and Dylan are your instruments. But how does that manifest itself in actuality? It sounds like the split was somewhat decided for you, but do you work together on the broad strokes, or are you working off the ideas one comes up and you’re like, “I can build off that”?

Al: We have discussions pretty often.

Ram: Yeah, and I think it’s not as linear as you might think. It always seems linear once it’s been executed, but I think there is this case of we both come back with “Okay, this is what I think I want to do.” But we also come back with “And I think if you did this, it would do this cool thing where something I’m setting up is getting paid off in your bit.” You’re both pushing and pulling at an idea, and so the shape that you end up with at the end of it does those things for both of your narratives, if you would.

Al: Yeah, it’s getting into a rhythm.

Ram: It’s exactly like a band. It’s not like the vocalist writes his parts and then sends it to a guitarist and then goes, “Yeah, now your turn. You do whatever you want.” No, it is genuinely a question of playing both parts together and going, “Oh, if you did this and if I did this, then the end result of it would be interesting.” And so it does genuinely work on that collaborative level.

So, it’s kind of like jazz or a jam band, where you start picking up on what somebody’s doing and then you start playing together, and you find the right answer together through your individual answers, if that makes sense.

Al: It’s definitely like that.

Ram: I remember being at Thought Bubble with Al, and we were just sitting down for a meal after one of the convention days. And there is this moment at the end of issue seven, the beginning of issue eight, that I think we firmed up just over a conversation. And as people read (those issues), that is such a pivotal moment. And to think, we firmed that up over, what, a burger?

Al: It wasn’t even that. It was a retailer chat and we were waiting for… I think because of COVID, we were a little ginger about getting into rooms with a lot of people, so we were having a chat downstairs.

Ram: I think it was just over drinks, not even food.

Al: Not even booze. Just a couple Cokes. And we like, “Well, while we’re here, let’s do a quick chat about this bit.” It was just a really smooth back and forth about, “Okay, if I put this here…” because there’s the 7-8 cliffhanger, the 9-10 cliffhanger. I feel like I can say these numbers and they won’t mean anything until you read issues.

I just want to say that there’s the issue eight solicit that I read last night and it’s actually pretty incredible. It says, “If you buy no other issue of Venom in 2022, you must buy this one and the next two, but start with this one.” They clearly want to hype up those issues.

Al: I don’t write the solicits on this one. I do on other things. I do on the X-Men.

Ram: I mean, to be honest, I don’t think the solicits have any actual correlation. (laughs)

Al: They’ve got enough correlations to give people an idea of how many copies to put in their shop. Which is what they’re for. The ones I write myself, I’m always a little bad about writing them for the potential reader rather than the retailer, but I’m trying to get better at that. I’m trying to put in more “And you’ll want order this many copies because this happens” without giving away the story.

Ram: I always get questions about solicits on Twitter or Instagram, and I just look at that and go, “Man, why would I be answering? Don’t read the solicits. Just read the book.” If you’re a reader, you don’t need to read the solicits. Just read the book.

Al: They’re treated like trailers for movies but they’re a very different thing. Or maybe not. I don’t know how cinemas work.

Ram: I think that is exactly the case, and that’s why I went into watching Pig expecting a John Wick but with a pig in it. (laughs)

Al: Oh, no.

So, you’re riffing. You’re jamming. You’re figuring out things over Cokes. What is an example you can share of how the process works? An actual application of it? Is there something from the first six issues that have been released where maybe one of you came up with a beat and you were like, “Oh, that’s good,” and then you built off of that?

Al: Would you say the issue four thing? The Eddie appearance in issue four, is a good… I mean…we can’t go too deep on that.

Ram: Yeah, there are still unrevealed things. (laughs) But I think that’s a good example.

Al: We went back and forth a lot on that one scene.

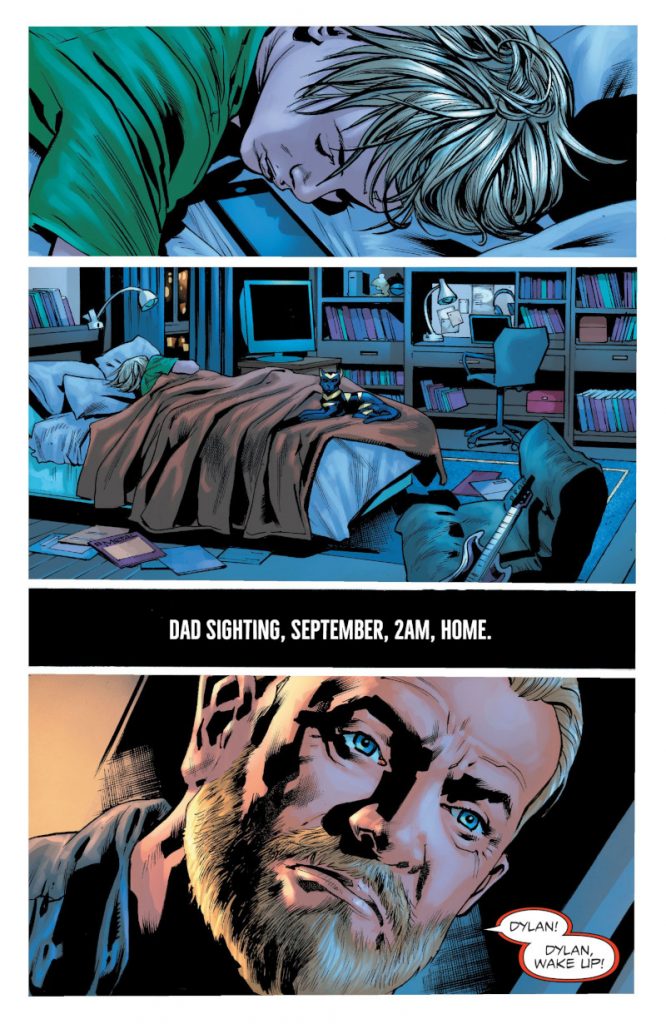

Ram: Also, the Eddie showing up at the end of issue #1 in the apartment with Dylan and then covering that again in issue five.

Al: Now, we know what that was. That’s a much better example.

Ram: I don’t think that as a concept existed until we had written issue one and we were like, “Wait, we could come back to this moment and make it really cool and make it the point where we reveal what is going on with Eddie.”

Al: I think Ram, it was you who came up with “This would be a really effective scene. This would a really creepy thing to happen, and it’d immediately build a big mystery.” And then I think I was like, “Okay, and then let’s solve that mystery in issue five.” So, in the first trade, you got the whole thing. We don’t leave readers on the hook for too long about that one thing.

Ram: But also, every revelation introduces two more questions. For every answer, there’s more questions.

Al: I’m loving reading people’s theories. I try to avoid online conversation, but I dip in every so often to get what people are guessing, and that’s a lot of fun. I don’t think anybody’s got it right now.

Obviously, fans love theories. But sometimes, they want payoff up front. And you two are very good long-term planners. Immortal Hulk’s a great example of that. Swamp Thing is paying off things further down the line. But this one, even from the Free Comic Book Day issue, you read that, and it doesn’t strike me as an effort that you two only have an arc or two planned. You could go for a while and keep building on this in a very real way. How do you balance the long-term storytelling with these types of stories? Not just Venom, but these types of stories with short-term payoff in a medium where readers very much are “What have you done for me lately?”

Al: I feel like we’ve built scaffolding up to, I want to say, around issue 30 or 35.

Ram: Yeah.

Al: In that we’ve talked that far. And obviously, this is all the vagaries of sales, the vagaries of the future. Who knows? Marvel could sell Venom to Fortnite and then suddenly, we’re writing Fortnite comics. I said this deliberately stupid thing, but now it’s going to happen. (laughs)

I was like, “That is way too believable.”

Ram: Bleeding Cool article. Al Ewing announces… (laughs)

Al: God, they’ll do that as well.

We have the bones or, in some cases, we’re still putting the bones in place. But we’ve got a rough idea of what the skeleton looks like. And then I feel like in the moment as we’re writing, the scaffolding becomes a jungle gym where we’re just clambering around it and swinging around and having fun doing what we want with the larger bones in mind. But putting flesh on them is a day to day. That’s how it is for me, anyway.

Ram: My mind goes back to something Kieron (Gillen) mentioned once about comics, especially monthly comics. How they’re fractal in nature, in that every issue is a story, but then every trade is also a unit of story, and then every arc is a unit of story, and every grand narrative is a unit of story.

And so, there are things set up and paid off within each of those units. The promise of one issue is usually paid off within that issue, but it generates questions and cliffhangers for you to go onto the next one. And then you realize only as you’re reading through three or four issues of a trade, “Oh, issue #5 is paying off what was said in issue #1 in an interesting way.” And then as you go through an arc, you will probably realize at the end of issue #10 that we’re still paying off stuff that was set up in issue one as well. I think it’s quite useful to think of story structure like that, where they’re nested question-and-answer payoffs within larger question-and-answer payoffs.

Al: I’ve definitely started thinking of the trade as a big comic. But I feel like back in the noughties, 1 writing for the trade reached its zenith in terms of decompression and these other tools. It was a thing that people explored and explored to the outer limits of that becoming useful. And we’re taking those lessons and starting to apply those lessons in terms of like, “Okay, the comic is a unit. The trade is a unit. The story as a whole is a unit,” and doing all of these different levels at once.

And with Venom, I was thinking, “Okay, well one to five is a block. Six to 10 as a block,” and on and on. I try to think of that with everything these days because with Marvel, it’s fairly standard. Occasionally, you’ll get six issue trades or even seven issue trades. But generally speaking, if you think in fives, you’re on the right track.

It’s interesting to think of all this through the context of the reader, just because there are so many different ways that people read things these days. When you’re talking about the whole as a chunk, where you’re going to look back at the end, I think about a conversation I had with Dan Slott once. When he started doing Superior Spider-Man, he was getting angry messages constantly. “How could you do this to Peter Parker?” And then at the end of it, when it was all done, he had the same people saying, “I loved this.” You were talking about fan theories, Al. You’re talking about how people are developing their ideas for this. It does seem like…not that you’re going to adjust your plan, but maybe in that jungle gym you can start playing with reader expectations.

Ram: I think that is inherent in setting up any story. You always want to set up expectations and defy them, pay them off, but also set up new expectations. So, I think that idea is inherent, whether you’re looking at genre, big action blockbusters or even if you’re looking at interesting literary stuff, there’s always scene one, you establish some expectation and then by the end of it, you have to have defied in some way. Otherwise, it’s just predictable.

Al: I feel like all this stuff, it’s kind of baked in. If we’re going, “Oh, maybe this is going to happen,” and then that happens, that’s kind of… There’s something to be said for the Greek tragedy, where you’ve got the chorus going, “Hey, just you wait. Things are going to get bad,” but I feel like that’s a mode of storytelling that maybe…You could do it. You could have “This terrible thing is going to happen,” and then it happens. That’s perfectly valid.

Ram: But also in that case, then the joy is in watching just how terribly it happens, you know?

Al: True, true.

Ram: I knew it was going to happen. I didn’t think it was going to be this bad. (laughs)

Al: There’s got to be something to surprise the reader.

That makes sense. Let’s talk about the overall architecture of the story. Obviously, you’re following Donny and Ryan’s run and you knew where they were ending as you were planning. That was something you were able to build off and everything. How different is it following a run like that versus something like Mighty Avengers, where it’s a new thing, or Swamp Thing, where you’re building off something before, Ram, but at the same time it’s a new character where you’re able to take it in a new direction? Does that change the arithmetic of how you approach a story like this?

Al: Not in this case. I don’t think either of us ever thought for a second, “Oh man, we’re writing issue #201.” We’re writing issue #1.

Ram: If at all there was a moment to think of it, it was knowing that any Swamp Thing run is going to constantly be compared to (Alan) Moore. Anything anyone does with the character is going to be constantly compared to that run. And that run, for me at least, is very influential in my own appreciation and understanding of comics. So if I can jump into that and not be tied down by what came before, but be fueled by it, then I could jump into anything and not be awed by the occasion, if you will.

I think the joy of comics is in looking at everything that came before as fuel and as material. For me, it’s like, “Oh, cool. It’s my turn at the wheel now. Bet you didn’t think I was going to go off road here.”

Al: I mean, I realized we have just…We are now saying that Donny is the Alan Moore of Venom (laughs) which I’m sure will please him a great deal.

Ram: Not my words. (laughs)

Al: It is that thing of, “We can’t just build a wing on the house.” We’ve got to start building a new house with the foundations that we have.

Tying into this, I wanted to bring up continuity. You both use continuity well. You use it in the story without ever making it feel overwhelming, which is one of the things I think concerns people about it. It can start to feel like an unpassable test where it’s like, “I don’t know everything that ever happened to these characters, so it doesn’t work.” But what do you view continuity as? Is it a tool? Is it a measuring stick? Is it just these people’s lives? How do you view that and how do you properly use it, whether it’s in Venom or anything else?

Ram: I think the best analogy for me for continuity is it’s the cityscape in the background. It’s the mountain at the horizon. That is everything that has happened, and so everything that is happening now will forever have it. But that’s all there is. You’re looking at the shape of the thing and not at the details. You can’t see every tree on the mountain. You can’t see every road on the mountain. You can only see the larger shape of it. And that shape has an influence on the story going forward, but it’s just like having a mountain (back there). All you need to do is look one at it and you know what it is.

You don’t need the details. You don’t need the years of preceding, nuanced knowledge about what happened to the character because that detail doesn’t matter. It’s what it did in terms of providing context to the story right now, that that matters. And I feel like this is very often a struggle that you get with people who look into the writing process from the outside and they go, “Oh, we need to explain to readers who this is.” I’m like, “No, no.” Everything the readers need to know is within the scene, so any information you’re giving is just information for information’s sake.

No, one’s going to go back and pick out a comic from 40 years ago just to read that one character so they have context for what’s happening right now. I mean, there might be people, but that’s going to be a rare thing. If anything, the useful nature of continuity is to provide flavor and context, but not necessarily provide detail.

Al: It’s tricky because there’s that completionist thing. But I’ve found that it’s possible to bring something in that’s just ancient, this tiny aspect, and just make it obvious how it’s useful and relevant now in the present moment. It doesn’t take much at all. And then it goes from being a chore where you have to go back and hunt through Marvel Unlimited and Wikipedia and all this stuff for a little Easter egg where “Oh, if you happen to have read a certain comic, that’ll give you an extra little frisson. But if you haven’t, you’re not missing anything.”

The other thing about continuity is that it’s either useful or it’s not. And if it’s not, then it’s really easy to just remove it. You never have to explain. People have given me this reputation of being very respectful to continuity, and it’s more that I see the use and the practicality of it. I see how it can add flavor.

Ram: You take what is useful to you and use it well.

Al: Yeah. It adds flavor. It adds depth. It rounds things out. It makes things feel three dimensional. The second there’s a bit of continuity that’s not useful to me this sounds like I’m just constantly ripping up other people’s stories, and it’s not that. But it’s, “I don’t need to go into every little thing. I can move past something.”

I listen to CEREBRO, the X-Men podcast, every so often. Not all the time, but when I’m doing something for a couple of hours, and I need something to keep my brain busy because it’s great. But Connor (Goldsmith, CEREBRO’s host) in that has a thing he says, which is, “Just don’t worry about it.” He’ll bring something up and say, “And then this happens. Don’t worry about it.” And that’s such a useful phrase because so much of continuity can be filed under, “Don’t worry about it.”

And then you’re just left with the really interesting stuff. Sometimes that’s teeny, little things that just resonate or have synchronicity with what you’re doing. But a whole bunch of it is just “Don’t worry about it.”

Ram: On that note, I think the real comparable thing is to look at comics as modern-day mythologies. Actual mythologies that have formed the basis for a lot of religions now, but if you go and look at original Greco-Roman mythology or you look at Hindu mythology, for that matter, what you notice is it’s full of contradictions because writer A, who wrote the first chunk, did something with continuity that writer B didn’t want to follow, and then just changed it. And then by the time you are reading it, so many hundreds of years have passed that the continuity is now reconciling with the fact that there is a contradiction…and it’s okay.

I think people who in the present go, “But X, Y, Z happened 50 years ago and this doesn’t account for that,” are missing the point. No, the contradiction is what makes it sprawling and beautiful and interesting and engaging.

I think we genuinely are writing modern-day mythologies.

This continuity talk reminds me of something. I did an oral history of the Marvel event Annihilation a few years back, and I talked to Keith Giffen for it. He was obsessed with putting Groot and Rocket Raccoon into that story. And nobody knew who the hell Groot was. Groot was a character that showed up for the first time in 1960. He was a Kirby monster.

Al: Yeah. He was.

And he basically had not showed up since. And (Giffen) just thought it was hilarious, the idea of this tree carrying around a raccoon that loves using heavy artillery. He thought it was the funniest idea. And eventually, he put it in Annihilation Conquest: Star-Lord. And now millions of people have toys of Groot. And that’s like what you were saying. If continuity is useful for you in that story, whether it’s because it’s funny like Keith thought it was or if it just happens to solve this problem that you have, that’s a good thing. But don’t worry about it otherwise.

Al: I feel like with a lot of that, to speak specifically about the space stuff and Annihilation, there’s a lot of stuff that has fallen by the wayside a little bit, even in the short span of time between now and the mid-noughties. It’s fallen by the wayside because it wasn’t super useful. Nobody’s destroyed it. But it’s been quietly left in the drawer until it becomes necessary again. And part of that is the Guardians (of the Galaxy) went from a future alternate universe to something in the present day that then grew out of Annihilation to the movie thing, which is kind of a streamlining of all of the space characters into a top five, because I think the original Guardians had Adam Warlock and Mantis.

And Yondu.

Al: But it’s like, “Okay, a super team of five great characters,” that’s a form of the continuity. And it’s extreme because obviously, the Hollywood movies are their own thing, but that’s a form of that in terms of like, “We’ve got to do a two-hour movie. What’s the most streamlined, most efficient, most useful version of this continuity to put up there on the big screen?” And then that echoes and reverberates, and we flow with it and we push against it on the comic front.

In regards to Marvel Cosmic, you’ve done a lot of stuff there, Al. Your story The Last Annihilation 2 was referenced in the first issue of Venom. It noted the Dormammu Invasion and everything. That’s another example of where it’s just a nod to something happening because it was a big thing in Marvel continuity.

Ram, I’m going to admit. I haven’t read Carnage yet because my comic shop has still not got comics in this week. 3 But I am interested in how that book fits. You have Carnage. Carnage is a symbiote. Is that something that you factor in here? I’m not saying that all of a sudden Meridius is going to show up over there or something like that. It’s a completely different story. But did that spill out of this and work off what you’re building here?

Ram: Al is absolutely caught up and part of the ideation process for what we did on Carnage.

Al: Yeah, I’m seeing all this stuff.

Ram: And with intent, with direction, because there is no Carnage without Venom, right?

Right.

Ram: Just conceptually. I like the idea that there is this inherent rivalry that continues to exist, regardless of whether the characters are right next to each other on the page or not. And I think people will start seeing that as the story progresses on Carnage behind what Carnage’s motivations are, if you will, on that level. And I think, without giving way too much, it’s safe to say that those motivations will collide at some point across books.

Al: The Venom-Carnage link is a very obvious one, but there’s a thing coming up that gave us an opportunity to look into upcoming things, and I forged a very strong link in that with something else I’m doing.

See? I’m tiptoeing around the land mines.

Ram: To a point where you’re realizing, “Wait, this is not really making sense.” (laughs)

This is a trap.

Al: If I talk about the upside-down engine, then that’s a link. So these links, they spread out into other places. It’s not always the ending.

I don’t even know if this is an offshoot of continuity. I think this is just part of continuity, but Al, it seems like when you’re working on something like this, and you previously worked on cosmic stuff…Actually, you have X-Men Red coming up, and that’s connected to all that.

Al: That’s sort of space.

I don’t know where the line is between space and cosmic for Marvel.

Al: If you’re talking to a giant humanoid who represents a concept, that’s cosmic. If you’re talking to a Skrull, that’s space.

So, you’re dealing with space stuff.

Al: Yeah.

When you have these different projects, whether it’s Carnage or you have X-Men Red or whatever, it seems like building tethers between those is valuable. You don’t have to use that as plot, but you can use that as something you can pick up later if you want. And that makes it an interesting tool.

Al: Sometimes, it’s laying down little pipelines you can make use of later. Sometimes, it’s just flavor. And sometimes it’s both. Sometimes, you do something that you know very diligent readers who are reading everything are going to pick up on. And sometimes, you know exactly how you’re going to use that down the line. And sometimes, it’s just like, “Oh, here’s a fun little pair. Here’s a fun little connection.” And then later on, an idea comes to you and “Oh, I can use that.” And stuff grows.

Ram: It’s also a matter of wanting to give readers a sense that there’s a larger world that exists outside of the pages that they’re reading. I think that’s a very underrated yet very fulfilling thing to see in a comic where you feel like, “Oh, an explosion that might’ve happened in the pages of some other book, I could hear it in this one,” or “I could feel the shock wave in this one.” And I think that’s very useful in conveying to people the sense of there’s something big that they are reading within.

Al: The reason Marvel has just taken over the world of movies in the way that they have, I feel like at least to begin with, that was the shared universe. Which is an innovation to movies outside of sequels, prequels and that kind of thing, but to spread out sideways like that? It’s incredibly potent. It’s incredibly potent just have a whole world and be able to go into that world at different points and see all the connections.

Ram: It’s building modern-day mythologies.

Al: My very first Marvel comic was Secret Wars, 4 so I was…

Ram: Very much steeped in that.

Al: Very steeped in it. But also, around that time it’s the Mutant Massacre, which was like yeah, you’d pick up a comic and there’d be an expectation of this will affect others right down to individual storylines.

There was that storyline in Thor where for an issue, the Casket of Ancient Winters gets broken open and it’s snowing everywhere. And in all the other Marvel comics, in the middle of July or whatever, there’s a bit where Spider-Man suddenly encounters this sudden snowfall and it’s like, “What is this?” And to him, it’s just a freaky thing. But if you’ve been reading Thor, you know. I can’t remember if there was a little editorial caption saying, “Yeah, pick up Thor.” But that was great. That really sold me on the cohesion of the shared universe.

Ram: It’s also very potent after the fact. You may have read the Spider-Man issue, seen this note and go, “Well, that was weird,” and not known. But five years down the line, someone points out, “Oh, that was because this thing happened in Thor.” All of a sudden, your brain is delighted by the idea that “Oh, I’ve discovered something that has just expanded the context for what I read.”

Al: I feel like a fun thing about this Venom series is that we’re doing that in one book, where it’s all of the fun of a shared universe in one book.

Ram: It absolutely is.

Al: Now, that’s great.

Like I said before, I’m not a giant Venom fan typically. But that was one of the things that I loved about the first issue. The scope of it was so big. You went from this very grounded story of Dylan being upset that his dad’s gone, understandably, and then you cut to his dad morphing between symbiotes as they investigate a ship in the middle of space and the scope of that is incredible. It wasn’t a typical Venom story. But Ram, you said earlier about how your process is not as linear as it might seem. That makes sense, as the story itself is not as linear as it might seem. I mean, you have people falling through time.

Ram: I think that is why we are able to tell the story the way it’s structured and still have it be cohesive, is because the way it’s created is not necessarily what comes after this. But it’s created in that “Here’s this organic-growing dendrite. Let’s hold onto some branches and try and swing to the next one.”

Al: I’d say we’ve built the bones of a thing, but it’s within the framework. I feel like the beginning, middle and end that we’ve got is really solid, and it takes something like a seismically good idea to shake that at this point. But within that, if a new idea comes along that we can build in, we’re flexible enough to do that, I feel like.

Ram: I also like the fact that there’s this lovely mirroring of the two narratives where you’re right, the Dylan narrative starts off really grounded. But as it goes on, it’s leaping and reaching forward toward the larger scope of the other narrative. And the Eddie narrative just starts out, boom, spread across time and space. And then as it goes on, I feel like it keeps getting focused on “Okay, this is what I need to do now to fix this.”

And so, they’re going to both arrive at this midpoint where both stories have matched each other in scope and stakes, if you will. And that’s going to be super rewarding to see by someone who has been following this thing that seems to be going all over the place to begin with, and to see that come in and collide.

Al: We’ve set up all these data points, and the more we start drawing lines between them and showing the lines between them and showing where they go and what they build up to, that’s going to be very… there’s some fun stuff that we’ve locked in. There’s some very fun stuff coming up that once the reader can see more and more and more of those connections, that sense of anticipation will build. It’s going to be a lot of fun.

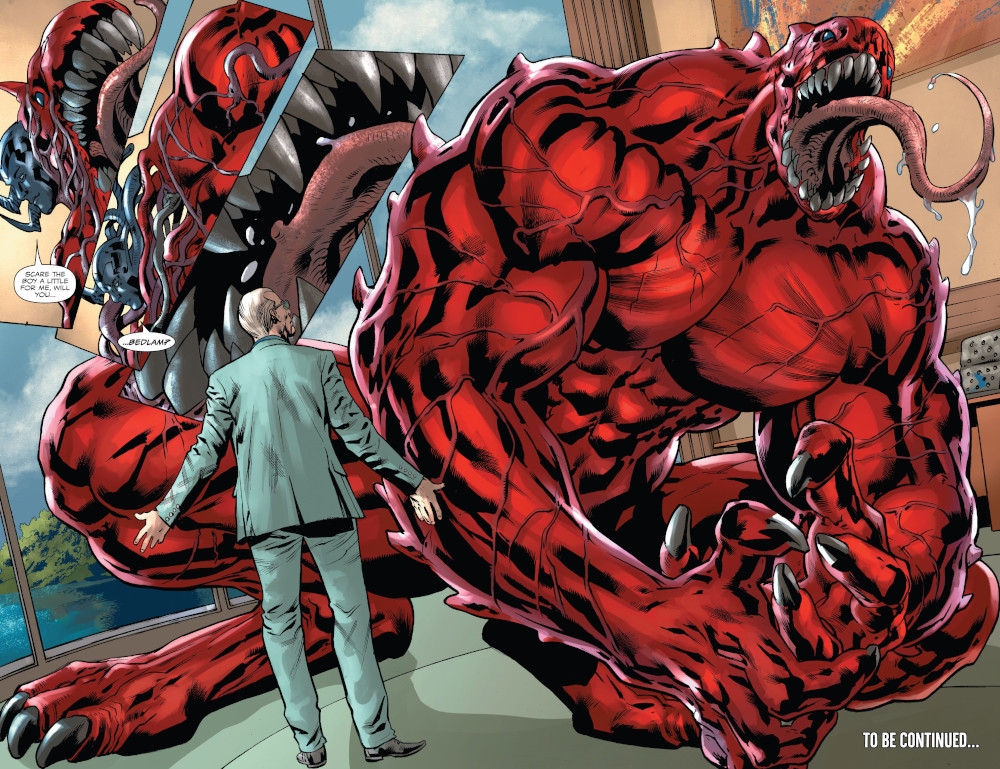

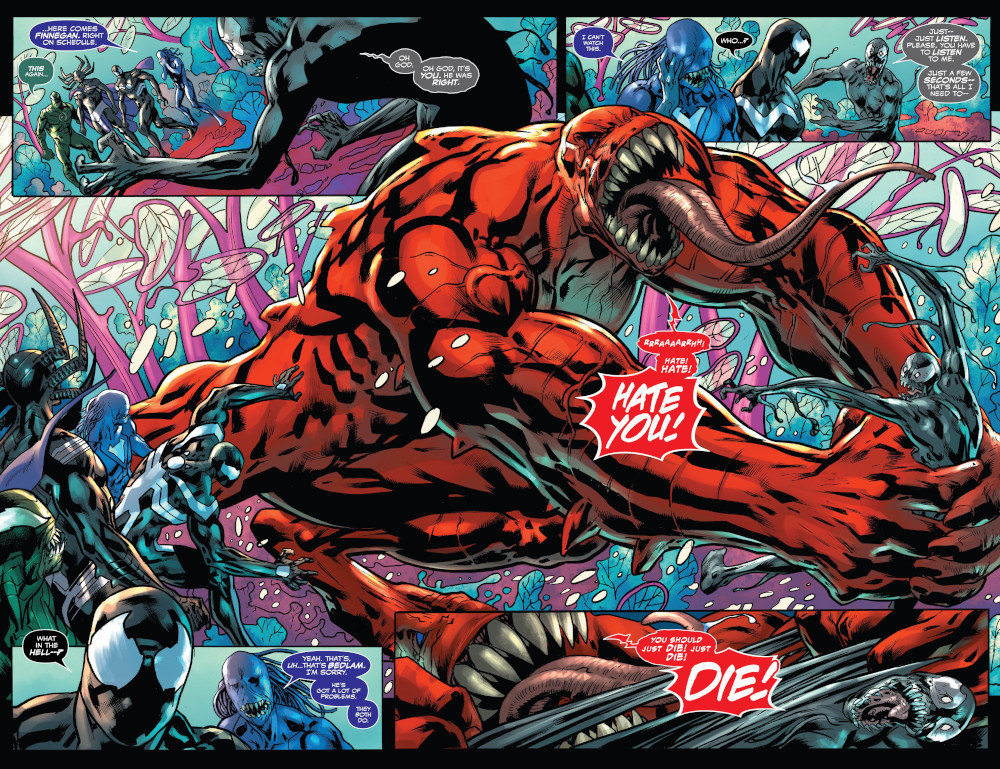

Obviously, Donny and Ryan expanded the idea of the scope of symbiotes in general. But then you can keep building on it. It’s interesting to see how can promise Bedlam in the first issue, and then you can introduce Bedlam in, I think, when Eddie goes to the garden in the fifth issue. And then Bedlam can be one of those things that gets sent to Dylan and all of a sudden, that’s where the bridge starts getting formed. And it is interesting how you can use the mythology of the symbiotes almost as the tie that’s bringing them together, in some ways.

Ram: I think that is absolutely how these things should be used, where the mythology serves to create interesting drama and conflict for your story. A lot of people always come up and say, “Hey, you’ve got this years of mythology that is all over the place. How are you reconciling?” I’m like, “No, I don’t have to reconcile it.” It’s great that it’s all over the place because that means I can do whatever the hell I want and find a way to justify it, you know?

There’s joy in that.

Al: Yeah. I do get a big kick out of taking completely disparate things from completely disparate people over different decades and just going, “Oh, man. If I fit this into here and this into here and put this in here and this into here, I’ve got a nice little story in.” (laughs) 5

One thing that’s interesting about what you do is, and I think everyone does this, but (Jim McDermott) wrote an oral history of the Five Years Later run of the Legion of Super-Heroes for my site, and you had mentioned how you took something from Legion because you loved that story so much and you worked that into your Guardians run, where basically was everybody had jackets, right?

Al: I’m always trying to do that.

We’re talking about how linear things are. It’s not just linear in time. It’s also linear in all stories. You can factor things like that in there, and it’s not that you can only pull from Venom history. You can pull from the history that’s in your mind of stories you’ve loved from the past if you so desire.

Al: I mean, you were saying earlier about Rocket and Groot and how that was Keith Giffen indulging a personal whim. It’s become this billion-dollar juggernaut that has long since left his hands and been subsumed into the mightiness of Marvel. And not to say that the only value in something is what it can make in merch. We’ve got a lot of really good Rocket and Groot stories. Just on the level of stories, we have so many good stories out of that decision to just take a couple of little, relatively small patches and put them together and say, “Let’s see what you can get from that,” and plug that into something else.

And it’s that kind of thing. I’ve had a lot of fun telling Rocket stories since then. I’ve had a lot of fun with Groot. So many people had a lot of fun with Groot. He’s a really fun character, and has evolved into a really fun character. It’s worlds away from the “I will now take over the earth. Oh, no. Termites” beginning. All this stuff has been built from this.

The point there is that you don’t really know what is going to turn out to be the whim that strikes you, whether that’s going to just be something that you did for fun and then you stop writing the book and that’s not happening, or whether it’s going to be something that other writers are going to just pick up on and grow and build into a thing that’s going to become super important. I don’t think you can plan for these things. It’s worth just giving into that impulse sometimes and just putting stuff together from the past.

It’s interesting listening to you talk about the way that creators work from one point to a later point, because it reminds me of what you all were saying about how you work together on Venom, where it’s the call and response, to a certain degree. And it almost feels like that that’s the case for when you’re writing Ultimates or you’re writing Immortal Hulk. Immortal Hulk’s a perfect example. When you were writing Immortal Hulk, it has that call and response, too, except for it doesn’t have that co-writer there. It’s like your partner, in that case, is everyone who has written the Hulk before then.

Al: I use the word synchronicity a lot about writing, but there’s a lot of stuff where you kind of… It’s a little bit of that numerology thing where you’re looking for the pattern and the pattern appears.

But there’s so much on paper and in Marvel Unlimited and not in Marvel Unlimited, things that are so obscure that they haven’t been added to the database yet, but there’s stuff that’s I’m sure has just been lost, like stuff from the ’40s that is just not around but is technically Marvel history. Certainly, this was the case with Hulk. But once you start putting together a few small things into a little hypothesis, you really can just go back and find whatever you need to find to support that. And what you start finding, and this is always a lot of fun, is that you find something at random and it feels like it was written explicitly to tie into your thing.

Something you’d never even considered that’s from the ’70s or whatever or the ’80s, and it just couldn’t possibly have been thought of this way, and yet it fits perfectly. I used to do a lot of what I call sampling. Just direct quotes of images and scenes and trying to get the dialogue as exact. Rather than rewriting it for the modern era, keeping it exact to how it was laid down, down to the stresses. Occasionally, I’d tweak it a little bit just in terms of tweaking the punctuation slightly. That always gives me a little (feeling), like somebody ran their fingernails down something. It’s like, “Oh no, it’s got to be exact.”

That’s the synchronicity, right?

Al: Yeah, yeah. It’s the synchronicity. You have got to keep it.

But there is that thing when you’re dealing with these giant shared universes that have been contributed to by literally thousands of people, it does just become this gestalt. I guess to swing it back to Venom, it becomes almost this unconscious thing, this kind of… I don’t want to get Jungian about it because I think there are too many people that misquote Jung, but that thing where it becomes this collective unconscious of all of these people going to their own wells, putting their own spin on other people’s. When so much of Marvel is coming out from Stan Lee in the ’60s to this whole bunch of people who were doing a lot of drugs in the ’70s, all getting their giant metaphors for their thoughts and their anxieties and their beliefs and interpersonal systems, and then the next generation makes them fight.

That’s a primordial soup of stuff that you can dive into. So, I do love these corporate-shared universes. Especially Marvel because during the forming of it, it was the most driven by all this subconscious stuff. Marvel in the ’70s, there was a lot of stuff going on with metaphor and psychedelia and acid. And then it coalesces like the Big Bang in the more corporate, streamlined work, the Jim Shooter thing of “Okay, right. Every comic is someone’s first. You got to start coalescing this stuff.” And meanwhile, I just reread all of Secret Wars II, and what is that if not Jim Shooter exploring his own hang-ups and metaphors and his idea of the ’80s, what his beliefs are in the middle of the age of consumerism.

Marvel does that very well, and I enjoy doing that as well. (laughs) I guess that is the Marvel tradition of the weird crank, putting a load of metaphorical madness on the page and building off in that direction.

Thanks for reading this debut edition of On Panel with writers Al Ewing and Ram V. If you enjoyed this conversation, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more features, interviews, longforms, and all kinds of other fun things.