INJ Culbard on the Process and Performances of Wild’s End

The Wild's End artist shares the story behind his work

In today’s era of information, where we’re being pummeled by a deluge of data and perspectives and opinions at every waking moment of our lives, surprises can be rare. The idea of true “sleeper” hits are more difficult to find than ever, no matter how often people love to use that phrase in relation to anything from movies to fantasy football. It’s because we know more than ever – or at least we have more access to information than ever – and the truly unexpected just doesn’t come around very often.

For me, one of the few places that still happens is with comics. That sounds strange, I’m sure. Comics come as a surprise to a guy who writes about comics all the time? Why would that ever happen? It’s because I don’t read solicits and, for the most part, don’t actually look and see what’s coming out before going to the shop. I do pre-order a lot of smaller books, but quite often, I find out what’s actually out when I get to the shop. I walk the racks at my comic shop and I look at the covers and decide what I’m going to get right then and there. Sometimes, that can be a less than ideal experience. But every once in a while, you find something spectacular.

For me, one of my favorite random finds I’ve had is Wild’s End, an anthropomorphic War of the Worlds type story set in the English countryside of yesteryear. This Boom! book from the team of Dan Abnett and INJ Culbard is an incredible, involving read, and it has only gotten better as it has moved into its second mini-series, The Enemy Within. One of the biggest reasons why is Culbard’s art, as he’s one of the industry’s best at storytelling and delivering characters with real humanity and personality. It’s a gorgeous title, and one I’ve been dying to talk to Culbard about since I started reading it. Today, you can read that chat, as Culbard and I talk about his process on the book, how it came together, why he’s stayed primarily outside of the American comic market, the coloring and lettering he does, and much more. Give it a read, and if you haven’t checked out the comic yet, you better. It’s a good one.

What’s your background in art? Did you go to school to study art, and if so, how important has that experience been in terms of the way your art has developed throughout your career?

IC: I’ve always drawn. Always. I’m a child of the seventies. Despite the best intentions of art teachers, I was caught in an education system that felt artists should become accountants (and look where that’s got us). So my education was a rebellious one. If people said you couldn’t become an artist, I was going to become an artist, and even then when attending art school I was told not to do comics so I did comics. If the odds were stacked against me it was always worth pursuing. And I have always wanted to do comics. Now you can study graphic novels at university, but in my day I fell into animation because I figured storyboarding was close enough, and that led to an animation career as a director. But I never let go of wanting to do comics. Everything I did in animation was always informed by comics. So, when my first son was born, and I say this in hindsight, I figured now’s as bad a time as any and switched careers. I must have liked the odds.

Looking at your library of work, I think one of the most interesting things is how successful you’ve been, yet how relatively few of your works you’ve done specifically in the American market. For me, the first thing I read from you (before going back to find other works, of course) was Wild’s End. Was sticking to comics that were British in origin – namely your varying Lovecraft and Doyle graphic novel adaptations and your 2000AD work – a deliberate choice or just where the opportunities were?

IC: Well, the UK has a substantial comics scene, and has had for many years. 2000AD for example. A very healthy crop of writers in the US market came from 2000AD. That is a beast of a comic and it’s been going for years. And now we have a particularly vibrant graphic novel scene.

And then there’s Europe which is has a insanely huge comic scene, where comics are culture, not subculture, and you have countless books. And so I read a lot of european comics. I’m a huge Mézières fan. I love Valerian and Laureline which is now being published in English by Cinebook. If you haven’t read it you should hurry up and read it. I picked it up after seeing Return of the Jedi. Loved it. Huge influence. The work I do is as a consequence of failing to be Mézières. And then you have Manga. Much of my pace and visual economy is from reading a lot of manga. Particularly the work of Katsuhiro Otomo. Particularly Domu. I’m half English and half Polish. During long summers in 80’s Poland I’d be in Warsawa Central station reading Ms. Tree books (in English) published in a paperback novel format. They’d have that in spinner wracks at the station. It was really a matter of reading whatever I could get my hands on, not just relying on comics from the US. But I read a lot of US comics too. Werewolf By Night, Captain America, Batman. Swamp Thing. I love Swamp Thing. Bissett’s incredible art. Such a scary book. And Chaykin, loved reading Blackhawk and The Shadow by Chaykin and the way he would use sound. He wrote really noisy comics. You name it, I probably read it.

Coming back to 2000AD, I mentioned it was a beast…it’s a HUGE rapacious beast that just eats and eats story on a weekly basis. To be a part of that now is fun and terrifying. You work on a series for that for six months, way in advance of the story going live, and it will eat that work in 12 weeks. I’ve even written for it now. I did a Future Shocks, which is how a lot of writers there start out. I am planning on doing more of those because that was a lot of fun.

I mentioned the Lovecraft and Doyle graphic novel adaptations you’ve done, with the latter a partnership with Ian Edginton. I thought those were especially interesting projects, as adaptations of classic works like that don’t happen that often in comics. Is there something that particularly appeals to you about adapting works like Lovecraft’s into the comic form?

IC: Well, with the Holmes books, Edginton and I wanted to present him as he is in the books, and the books are pretty pulpy. They’re very much adventures. With the Lovecraft it was an opportunity for me to write as well as draw, and I had a very fixed idea of what it was I wanted to do with that from the get go, looking at what it is about his work that’s inspired so many in the genre of horror. I didn’t want to produce a book full of captions and dense exposition. And Lovecraft can be very light on dialogue, At the Mountains of Madness especially so, yet you read my version and it’s full of dialogue, dialogue which I came up with taking my cues from the source material.

Wild’s End is a unique project for a lot of reasons – the anthropomorphic characters, the alien invasion angle, the very small-town British feel – and it’s those and a lot of others that I find it easy to love. What is it about that project that made it not just one you wanted to do with Dan Abnett, but also keep working on with future series like the current mini The Enemy Within?

IC: The first project Dan and I worked on together was New Deadwardians, which we did for Vertigo. Dan had read my adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness and got in touch with me with this idea for a Edwardian police procedural that just happened to have Vampires and Zombies in it. I called him up and we had the longest telephone conversation which involved a fair amount of world building, setting the rules for how our vampires functioned biologically to how they fit into the world politically. I love world building. I used to work in television and I’d write bibles for TV shows, so it’s not a completely new experience to me, but working on stuff with Dan in that way is a lot of fun. We kick around ideas, throw everything we’ve got in, and then end up with all these other ideas so it seemed pretty obvious, when we finished New Deadwardians, that we should try to come up with something else. What followed was another epic telephone conversation where we discussed a number of projects, most of which we’ve made now. ‘Dark Ages’, published by Dark Horse last year as a four part mini-series and has now been collected, ‘Brink’, which will be appearing in the pages of 2000AD next year and of course ‘Wild’s End’.

Everyone has a different way they create their own art, whether it’s straight digital, traditional or a mix of both. How do you work, and what’s your process for bringing an issue of The Enemy Within to life with Dan?

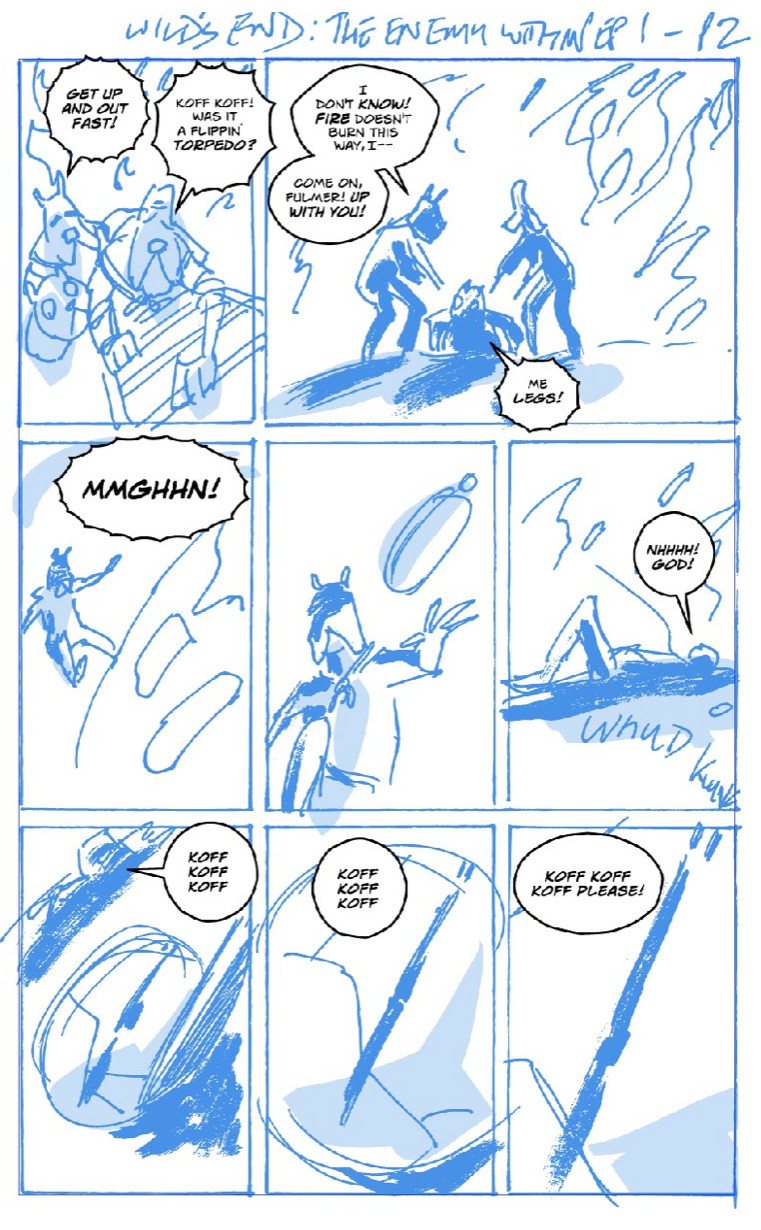

IC: I do horrible roughs which only I’m supposed to be able to read but somehow my editors, bless them, are able to read them. And then I take those roughs and work them up into more presentable drawings, and then go to color. Which all sounds very much like “how to draw an owl: Draw a circle, put a line through it, draw an owl” but it’s such a straight forward process for me, it’s all about making it as straightforward as possible.

I work digitally in Manga Studio which I’ve used since I started, and when I color and letter it’s all in photoshop and that’s it. I start out with thumbnails for the whole book, my roughs, I then spend a day just drawing the main character that feature the most in an issue, only drawing them. Because I have my layouts I have staging mapped out and know where they’ll be. And then the next day I spend the whole day drawing another character and so on till I draw all the backgrounds, and the book is then pretty much drawn. That way I’m able to focus my process. I don’t interrupt. I mean, as an artist you’re spinning a LOT of plates. You’re having to think about the character’s emotions, what they’re saying why they’re saying it, where they’re standing, what they’re wearing and so on. What I do is just break that down so I’m focused on one thing at a time. Not drawing a character then a supporting character and then a background and then repeating the process panel after panel as that breaks the process time and again and just leads to procrastination. I stay in character as it were which I think allows me to be subtle and affords the characters a consistent performance.

So, my average working day; in the morning I could be Clive, in the afternoon I’m Susan. It’s essentially like acting. I’d say the job of the artist is pretty much that, they’re the director, the actor, the set designer, the costume designer, the director of photography and so on. And if you think about it that way, it’s a LOT of plates to spin. So just spin them one at a time and try not to break any of them.

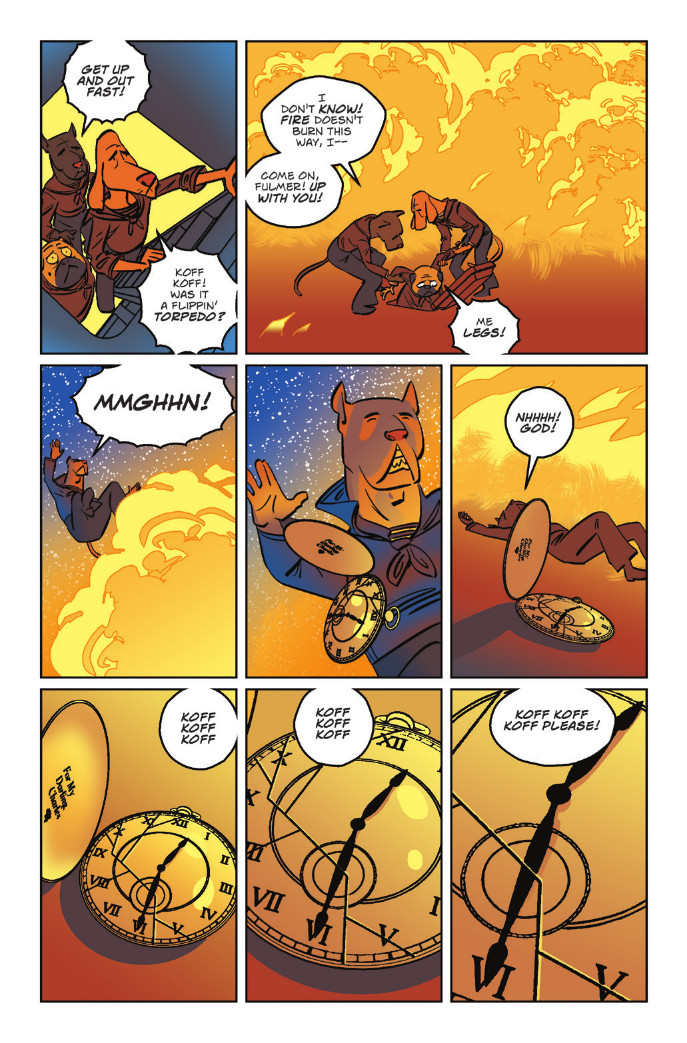

I really love this page and how it uses a modified 9-panel grid layout to slowly zoom in on Clive’s pocket watch. It’s a fantastic page that shows off how paneling can up the drama and show the passage of time to build drama. You talked about your layout phase already, but when you’re laying out an issue, what are your main goals? Is your primary goal clarity of storytelling?

IC: It’s something I picked up from storyboarding, but is also rooted in comics and in turn rooted in storyboarding again. This is the manga influences playing out. Tezuka first popularised the influence of storyboarding with his decompression techniques. This is where Manga plays a hand in my own storytelling because I’m essentially doing the same thing. When I was storyboarding we would thumbnail really rough and then commit to finished boards. The trick is really to get down what you’re seeing in your head as you’re imagining the story play out, and to get that down as quickly as possible. And roughs is the only way to do that. I liken it to reportage from the frontline of your imagination, which sounds corny as hell, but that’s pretty much what you’re doing. You’re seeing things and jotting it down in a shorthand. It can be stick figures, doesn’t matter, all that matters is that YOU can read it and just get it down as quickly as you can so you don’t lose that flow.

I’m always really embarrassed about my roughs because they are so rough.

After you put together your roughs, do you ever alter layouts, or do you try to stick to your original thought as much as you can?

IC: Yes, if I’m asked to by an editor, absolutely. It seldom happens. For example, issue 4 of Wilds, rough comments came back with a suggestion for one panel. I’m lucky. There’s never many. And then when it comes to the rough and the finished thing, there’s no strict rule. If in the process I come up with a better way I’ll do it. I never rule anything out. There has to be fluidity and flexibility because that’s story. I want the story to flow, I want it to ease it’s way to the reader, not march toward the reader in rigid uncompromising formation.

While I really love the look of all of the characters, these two newbies from The Enemy Within – Lewis Cornfelt and Herbert Runciman – are particularly fantastic. There’s just something about Runciman’s look of a literal fat cat that says a whole lot about who he is. When you and Dan were developing this book, how do the two of you decide what each character should be? Like, what made it apparent that Runciman needed to be a chubby orange tabby?

IC: Thank you. I think Dan is so incredibly focused on character, species doesn’t really matter at this point. He’s very open to what comes back. A lot of the stuff you see will often be the very thing that popped into my head. Or if Dan says it’s a cat, it’s a cat, I’ll go with that. The rule is ‘it just is’. There’s a good deal of ‘it just so happens to be this way’ and we work with it.

I really appreciate the subtleties of this page, specifically the up and down of Runciman’s newspaper as he goes back and forth between giving Cornfelt the time of his day. When it comes to the character acting on the page, how do you plot that out, and how different do you approach the mannerisms of each character in that regard?

IC: Well, it’s like I was saying with the process, in the morning I am Clive, in the afternoon I am Susan. Because I stay with that character and draw just them for the day I am in character for the whole thing, so there’s a consistency to their performance and it allows for things like subtlety and I love subtlety.

On this book, you’re not just drawing the book, but coloring and lettering it yourself. That’s not new for you, but I’m curious: is the reason for that a question of controlling all aspects of the look of the book – besides the design, which is Kara Leopard – or something else?

IC: I guess because I’m used to doing it all myself. I do that for all my Lovecraft books for SelfMadeHero, for every book I’ve done for them in fact. But I have, on occasion, worked with others and I’ve enjoyed that process. Ellie de Ville and Annie Parkhouse letter my work for 2000AD and on New Deadwardians, Travis Lanham lettered that book and Trish Mulvihill colored it beautifully.

When it comes to coloring the book, you don’t specifically go for simple, natural colors in backgrounds and beyond. It seems to me you focus more on mood. Would you agree with that? How do you like to use colors in your storytelling?

IC: Yes. Certainly. An extreme example of that would be that I like to put in the odd background panel not natural to the environment, so if a character is shocked or there’s violence, the bg is usually blank and there’s a color fill of red or orange that jars with the rest of the page for that reason. It’s supposed to pull you out in the same way a slap in the face would. I don’t always do it, it’s not a hard fast rule, just occasionally I’ll throw that in there.

Haven’t read Abnett and Culbard’s Wild’s End yet? Check out the first trade either in print or digitally. It’s a good one, and its follow-up series Wild’s End: The Enemy Within is being released now at comic shops everywhere.