SKTCHDxTiny Onion: Part Eight, Crafting a Debut

It’s time once again for one of my monthly chats with writer James Tynion IV, as the ongoing SKTCHDxTiny Onion interview series continues with a subject both James and I have thought about a whole lot: first issues, and what goes into making one of those pop. This conversation explores the crucial elements of a great debut, using a slew of Tynion’s biggest and best examples of that form as our focal points for this discussion. We’re going to get straight into it this time, but this interview — which has been edited for length and clarity — is open to non-subscribers. If you enjoy what you read, consider subscribing to SKTCHD and to Tynion’s The Empire of the Tiny Onion newsletter for more like it.

This month’s focus is on first issues and how you make them work. They’re essential for storytelling. They’re essential for the business of comics, although that’s not going to be the point here. And let’s be honest, they can be pretty exciting when you make them work. I mean, I’m not going to say that most of my favorite issues are first issues, but some of the ones that stand out the most are first issues and I think that’s for a good reason. How do you view first issues as a writer? Do you see them as the most important one, or just one that is disproportionately valuable to hooking readers, so it requires a bit more emphasis from you?

James: It’s definitely the most important one, and it’s the most important for a few different reasons. It’s everyone’s way into the series. It is the first time a retailer gets to see the book. The cover is usually the first image anybody sees of the book. Even once it’s collected into a trade, it is the first part that convinces the reader whether to put down the trade or continue reading. It’s fundamentally important. It’s something that needs to sell the entire idea of what the book is.

And then on top of that, it’s when I figure out the book creatively. It’s when the book starts telling you what works and what doesn’t and what you’ve been a little too ambitious about and what actually needs to be dialed up and what’s missing. So honestly, it’s one of my favorite things to do. I love writing a first issue.

It can be really stressful. They are the issues that I spend the most time on. They are the ones that I write and rewrite the most. I hit the most drafts on those issues because the whole system needs to come from that single issue.

I hadn’t really thought about the trade thing. I imagine a lot of people, if they read that first chapter and they’re like, “Nah, this isn’t for me,” they just won’t keep going. It’s kind of like the trial period. If you don’t get through that trial period, no one’s going to renew. You have to really nail that. Because otherwise you’re going to lose people across the board, whether it’s retailers, readers, trade readers, or whomever. And so that makes it essential.

James: It absolutely is. I cannot understate the importance of it. And I don’t understand sometimes…I mean, this will probably get into another part of the discussion, but you see the priorities that some creators bring into their first issue. And I love leaving mystery. I love not explaining things. There’s plenty I don’t explain in my first issues, but if you haven’t told me what the book is, you haven’t told me why I should keep reading. You have to tell the audience what they are reading so they know what to expect when they pick up issue two.

Let’s get into that, the essentials. Are there things you know you need to accomplish in a first issue as a writer? Things that you have to have? Obviously one of them is, what is this book? But what else is important for that first issue?

James: There are two essential things and they are basically the same thing. It’s just looking at it from two different sides. One is what is the book? What is the actual proposition you are making to the reader? What’s the reason to keep coming back month after month after month? That’s important to sell both to the reader and to the retailer picking it up, or to anyone who looks at it. You need to express that. The way to express that is through the feeling of the comic. And that’s what I spend a lot of time thinking about and working on, especially once I’ve cast the artist on the book and I start developing it and I start ripping it apart and putting it back together. It’s figuring out the vibe and then it’s expressing the vibe. The aesthetic texture of the comic itself is the thing that’s going to make it stand out on the shelves from everything else, stand out from my other work, but also tell you what series this is this similar to.

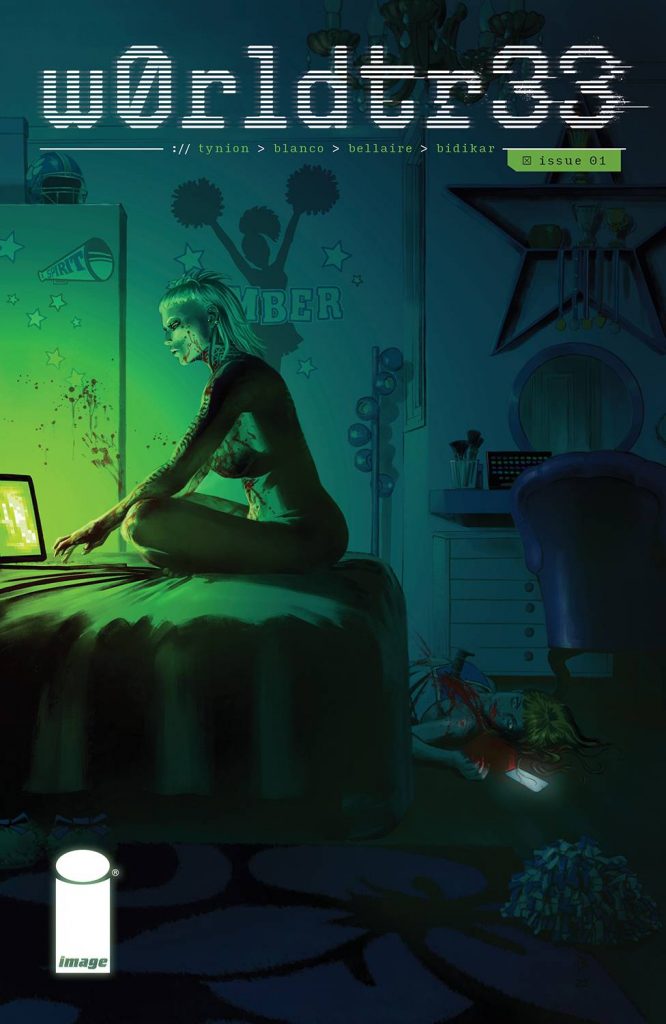

So if you like Nice House, you’re probably going to like w0rldtr33. They kind of operate on a similar system. There are little tells that you can sort of throw in there and there are little tricks like that, but it’s so much about capturing the vibe and capturing the sales proposition. And all of that really comes down to, what is the reason you as a creator want to make the book? Because at the end of the day, you were just expressing the reason you want to make this comic. So it’s one of those things where it’s easy to look at the sales side of that as a crass way to think about things because it’s thinking about it as commerce. But it’s really, how can you in clear terms express through the visual medium of comics why you want to tell this story and convince enough people to keep reading it so that you get to tell it to its full length.

This is actually eye-opening in some ways to me because when I think about it, what you’re talking about is you’re trying to establish what the vibe is, what you’re going towards, the idea of what’s to come, so you get hooked, so you keep going and everything like that. That makes me think of trailers and how trailers lead into the larger thing, and then how that relates to the idea of sampling in single issues and how sometimes people buy the first issue and they’re like, “You know what? I really like this. I’m just going to get in trade after that.” I was going to say that that’s a dangerous proposition, but I guess for you, if somebody buys the first issue and goes onto the second issue, that’s a win. But if someone else buys the first issue and then decides to buy the trade because they thought the first issue was great but want to read it in whole, that’s a win too.

James: It absolutely is. Anytime somebody decides to read more, it’s a win. Obviously picking up issue two is the best way to continue a series running. Single issue sales are still fundamentally important. But it is one of those things where it’s anytime somebody puts down that first issue and then they want to read more or they tell their friends that they read this first issue, it’s a win.

But there there’s a larger piece that the trailer question actually hits on really nicely, which is something that I remember talking about in the early days of my newsletter before the Substack grant. I would talk about pitching a little bit and the way I think about pitching. And pitching is a process that never stops. Some of this comes from the fact that my mom was in advertising and I grew up in a house thinking about advertising, and then my first job out of college was in advertising. There’s a bit of me that’s always going to be a bit of the salesman.

But I realized that an initial pitch document is…first, it’s me pitching to myself. It’s me putting all of the raw ideas in my head into a document and trying to be like, “Is this idea cool? Do these ideas mesh together? Is there an aesthetic vibe that I am excited to play in?” And if the answer is yes, then the second round is I go to one of my usual editors that works on these projects with me. Even if they’re not able to work on this project, sometimes I’ll reach out to my BOOM! or DC editor just being like, “Does this sound cool?” That gives me that second round of, “Okay, there’s heat here. It’s not just me.”

And then around that time, I sort of polish it and refine it down. I strip out a few elements, I put a few new elements in, and that’s when I start reaching out to the artists that I feel like are going to best express that vibe. And that’s the second time. First, I’m selling it to myself, then I’m selling it to my first readers. And then the third round is I’m trying to sell it to an artist. “Are you willing to give me a few years of your life to play in this world and make a really cool fucking comic?” And it’s finding someone who is just as enthusiastic as me, who then starts bringing their own ideas in and starts throwing things back at me. And then there’s the back and forth of just developing all of the key imagery and all of that. And we’ll talk about the idea of the key image, which I know I’ve talked about a million times, but that has become a central part of my development process.

Once I have all those pieces and I get a sense of how the book’s going to look, that’s when I throw out all my previous documents I’ve done to that point. Then I start thinking about what is the first issue. I have a cool central concept, I have a story I want to tell, I have characters that I want to tell those that story about, and I have an artist willing to go on this journey with me. Now the next step is I need to sell that to the world. And the first issue is how you sell that to the world. And so in selling that, you have to know what those essential pieces are, the pieces that you can’t ever strip away. And once you have it boiled down to that and you really focus on just how to make that best first issue possible, those priorities shape everything else.

I change a lot of things in the process of writing the first issue. There are usually characters that pop up that didn’t exist before, settings that I didn’t think were going to be important. Characters that I thought were going to be crucially important end up being very secondary. All of this ends up happening from that moment of writing the first issue. And then in seeing it drawn, you find out what worked and what didn’t.

That is a lengthy process. It’s either five or six steps and each of them are pretty big. But at a certain point, you have to get on a deadline-fueled rhythm, writing and creating. For the first issue, though, it’s a process. I am curious as to how long that tends to be for you. I know development can take quite a while. Let’s say for w0rldtr33, how long ago did you first get to step one where you’re like, “This is cool, I’m getting this together, I’m buying into my own idea. Time to go to editor X, or editor y, or editor DC?”

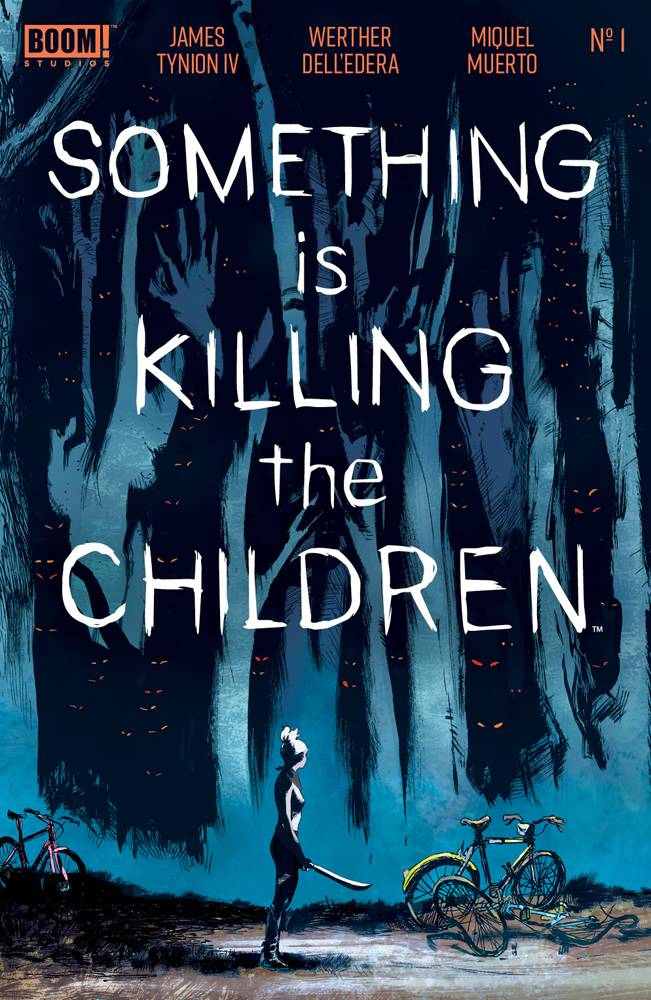

James: It was like four years ago, and the first step of it was…I had the raw concept. As in there’s an evil internet that lives beneath the internet and it rises up and the idea of a generational aspect to the story, I had those raw pieces. I knew what I wanted to talk about with the comic. I knew the nonfiction books and the movies and anime and comic books that were a part of that aesthetic blend that I wanted to talk about there. It was very early in the process. Honestly, w0rldtr33, I sort of see as the last book in the generation of titles that included Something Is Killing the Children, Department of Truth, Nice House, and now w0rldtr33, especially in my more adult-driven books. Those ideas came to me in a very short period of time.

The next step from there was starting to talk to an artist. I had been talking to Fernando Blanco for years about how we would love to work together on a creator-owned book. It was the summer of 2020 when we started sending emails back and forth, just about horror comics we liked and recommending each other books. And about six months into that process of back and forth emails, I asked, “Do you have any interest in this?” I sent him the raw idea of w0rldtr33. There was actually a central element of it that he thought was missing, which I can’t share because it spoils what happens next in the book. But that unlocked the last piece in terms of the plot structure of the entire thing for me.

So once I had all of those pieces, I was able to step it out. But I was working on a million books at the time. He was still working on Catwoman and it was the lead-in to his work on the backup stories in the Detective Comics he did with Matt Rosenberg. And so all of that kind of came together, and then he started boots-on-the-ground working on it last spring, about a year before the book actually came out in stores. It was a long process of that first issue and then also the design elements and figuring out the approach to covers and everything.

But then once we’re up and running and we have a locked date, that’s what starts kicking in the, “Issues now need to get done on a regular basis.” And then I frustrate my editors and co-creators a bit because I’m working on 20 things at the same time, but more or less everything comes out on time.

I don’t know if it’s still the case, but Image used to require teams to have, I think it was three issues in the can before you even launch. And so w0rldtr33 #1 must’ve been finished early 2023.

James: Yes.

If not earlier.

James: We wanted to be fully done before the New Year. I think there were still a few pages that needed to happen after that. But we were effectively done at the start of the new year. And Fernando has a very good pace. The first three issues were…usually the rule at Image has been you need three issues in the can before it’s solicited, which puts you pretty far ahead. If they can tell that you’re on a good pace, you can sort of speed that process up, but then it creates the risk of falling behind.

But I’m leaning hard into Something Is Killing the Children model, where it’s five months on, three months off, five months on, three months off. So if we’re running a little hot to press on issue five, that doesn’t bother me so much, because we’re going to catch back up. And then we’ll be able to continue to catch back up every arc.

It’s interesting to hear about this because I think a lot of people, when they think of first issues, they’re probably like, “Oh, James just sits down to write a first issue and he does it this, this, and this way, because that’s the way he does it.” But it seems like more than any other issue — and this is part of the reason it is so important — the first issue is basically the manifestation of all the work that precedes the entire process basically. Everything is brought into this first issue to make sure that whatever book you’re working on has a strong backbone to stand on.

James: Correct.

It’s interesting because I bet most people would be like, “Alright, when did the w0rldtr33 #1 process start?” And you’re like, “2019.” They’d probably be like, “You’re lying.” But no, that is actually when it started.

James: And here’s the real thing. There are 10 other ideas that I had around the same time that haven’t happened because…I had the raw idea, I got a few steps into that process, and then it’s just either schedules haven’t lined up yet. Which frankly, that’s the origin of what will be my first DSTLRY book. I’ve been talking about that with Christian Ward ever since I did a Swamp Thing story with him. It was part of Ram’s Swamp Thing Run. I forget when exactly. It was a Halloween special that was all different Swamp Thing stories, and we did a piece in that. And then a little bit later we did The Gardener one-shot for Batman: Fear State. And during that whole process, we were talking about Spectregraph.

The raw idea of Spectregraph was already in motion. It’s just now we’re sitting down to get it up and running. But that’s a multi-year process. Once you figure out what you want to do aesthetically, then you land on the artist that’s going to deliver that aesthetic vision and then enhance it and bring their own ideas to the table. And then you have to wait until the stars align, until both of you have room in your schedules.

And then you have to go, go, go, otherwise you’re going to lose him, because Christian’s a very popular guy.

James: Exactly. And then on top of that, he does a lot of work for himself. But sometimes that ends up being a helpful thing because maybe I’m somewhere sitting in a room looking at all of the things I have to do when I’m having a panic attack, because it’s like, “Oh god, how can I write the first issue of this thing?” And then all of a sudden I get an email from him where he says, “Hey, I just got a really cool opportunity to do a Batman book at Black Label.” And I’m like, “Yes, please go take that book. Give me another six months to get on this issue.”

Thank god. Because otherwise this spring would’ve been more difficult.

Until you said the panic attack part, I was actually envisioning you as Ozymandias from Watchmen. So I’m glad you said the panic attack part to differentiate you.

It sounds like you have a pretty set process for first issues in the sense that there are certain things you have to do in the process. But how standardized is your first issue approach? Are there things you know need to accomplish in each one, or is it all dependent on each project? Because titles like w0rldtr33 and Wynd probably have different needs. Do you have to approach them slightly differently?

James: Absolutely. And Wynd’s a really interesting one because I didn’t write that as single issues. For the purposes of this conversation, I don’t really consider it the same animal because I wrote it as an OGN that then we restructured into single issues and added scenes to make it function better.

But it’s still the first chapter.

James: It is the first chapter. The opening sequences of that and how I deliver the opening sequences of Wynd follow a lot of the same principles. You still have to sell the central conceit really early on. Honestly, that’s why Wynd starts with the nightmare. You see the nightmarish vision of what he could become, which starts the central tension of the entire book, because I know you’re not going to get the image of Wynd with wings until 200 pages later. But that’s the central image of the entire series, so it needs to exist early in the book as well, even if it’s in a more monstrous, nightmarish form. Those pieces are ingrained in me.

But I don’t have a process in terms of…I don’t sit down with a checklist. I don’t sit down and ask, “Is this accomplishing X, Y, and Z?” I feel my way through a lot of it. And I think the way that I feel it through each time is dictated by what I’m trying to talk about, especially if you look at my last creator-owned number ones. Wynd is an exception because it was created differently. The other exception is The Closet. I’m very proud of that first issue, and it does have all of these pieces, but The Closet’s more like a stage play and was also originally envisioned as an OGN. When I started writing the first scene of that, it’s the first chapter, but it’s not the first issue. I sort of think about it a little differently.

The sales proposition of Something Is Killing the Children #1, Department of Truth #1, Nice House #1, and w0rldtr33 #1…those were all me thinking in terms of, “This is my shot. I know I have this long-form series that I am trying to tell. If I don’t succeed in expressing that by the end of that first issue, then I’m not going to get people to come back.” And so there are certain things that I do very quickly.

From the get-go, I’m like, “I need more than a standard 24-page issue to accomplish that.” I think a 30-page issue is pretty much what you need to get all of the information out there. That used to be more standard. I know Vertigo number ones used to be oversized. The first issue of Preacher is an oversized first issue. I think that’s a good standard that we should go back to, because rather than cut an important piece out and move it to issue two, you want everything in that issue one.

But sometimes you hit budgetary concerns with all of that, which honestly was part of the impetus of why there are design pages in Nice House. I wanted more pages, but the budget of the book did not include more art pages. “Well, could we get those through design pages? And how can we make those design pages interesting?” Especially because I needed to sell the end of the world and I needed to sell it in two pages. And trying to solve a problem can create really creative solutions, which make the whole concept better.

You just brought up something I think is interesting. I’m not saying it’s necessary, but when it’s an oversized issue, you read that and you’re more invested because you get more of it in one chunk. A good example for that is Kelly Thompson and Meredith McLaren’s Black Cloak #1. It was very successful at that. It was triple-sized, so it was big as hell. And the fact that it was triple-sized was a big part of the reason I picked it up to begin with. Because from a consumer value standpoint, it felt like more.

James: Yeah.

Do you factor reader expectations into it? What their expectations are? To make sure that they finish the read satisfied? Because that that’s the thing with Nice House, it’s a little bit longer so it feels like a more satisfying chunk and you’re more hooked by it. And so what serves you as a writer serves us as readers.

James: I don’t want to make a comic that you can read in five minutes. That’s a central thing for me. It’s why I like dense comics. It’s why I use so many panels. I like to control how quickly the reader can read the book. And part of it is most of my work is rooted in horror. So, I’m also trying to control how quickly the reader reads it so I can have a handle on how I build and release tension. I always lean towards dense comics. And growing up, those were the comics that I was always drawn towards. It’s why I think that I’m better suited for a lot of what I do right now rather than more action-driven storytelling, though I still want to go back and crack how to do that in a more me way down the line. But it is something I spend a lot of time thinking about.

Another thing that I think is important, and it’s something I think that you do pretty well, is the final page, which is maybe the most important part of the first chapter. it’s the last taste you leave in somebody’s mouth. It’s really important because if you have a cliffhanger or if you have something where it’s just like, “Oh my God, this blew my mind,” you’re far more likely to pick up number two.

James: Yeah.

How important is the ending of the first issue to you?

James: It’s very important. Something that was ingrained in me at a very early point in writing comics, which is something that Scott Snyder told me, is the beginning of every comic asks a question and then the end of that single issue answers the question.

Oh, that’s good. Good job, Scott.

James: It doesn’t have to be a literal question, but it’s just like there is the ask and then the answer. So it’s just the beginning and the end. You need that circularity in the first issue. Once you’re past the first issue, you don’t need that circularity, I think. You can shake it up in a lot of different ways, but a first issue, you need that kind of hook.

The beginning of Something Is Killing the Children asks the question, “What the hell actually happened?” And you get the truth-or-dare scene, you get the James in the interrogation room being like, “I have no idea what happened,” because he’s afraid to say what he actually saw happen, because he knows it can’t be real. And then at the end, Erica Slaughter shows up and is just like, “There’s a monster in those woods and I’m here to kill it.” And then James asks, “Can I help?” And that last bit is actually the separate thing. That’s almost more the cliffhanger. But it’s not a cliffhanger. It’s not a hook in the same way, but it is the thing that carries forward.

I was texting some of my editors this morning, at least the ones that are on the same coast as me, so I’m not waking them up at 6:00 in the morning. But basically, I was asking them what the favorite of my first issues were from the last few years. And thankfully, every editor chose the book that they edit.

Shocking! Biased! (laughs)

James: But Eric Harburn, who’s been the editor on Something is Killing the Children and Wynd, and all my BOOM! titles going all the way back to the beginning of my career, he was the one who pointed out that Something is Killing the Children is sort of the model the rest of them follow. And it’s the one that I did not knowing that it was building a model. Yes, it has that circularity. It does the thing where it doesn’t answer any of the central questions of the mythology in the first issue, so the reader is asking themselves lots of questions. And then at the very end, it has that kind of downbeat hook rather than an upbeat hook. It’s basically a kind of melancholy like, “Oh God,” kind of moment.

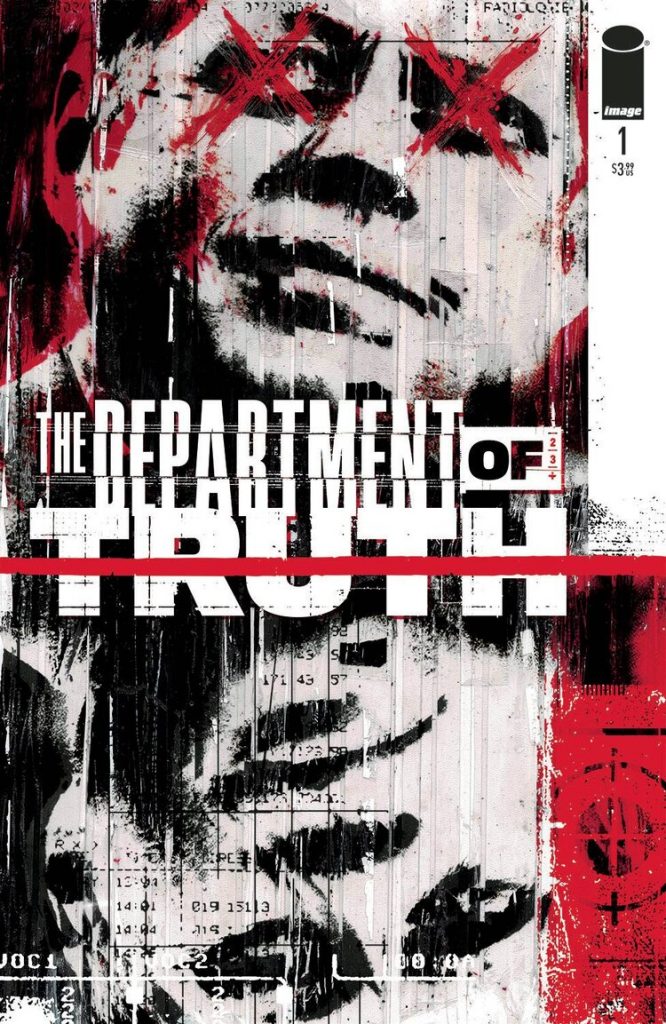

You’ve seen everything that this young boy James has been going through, and he doesn’t know what to do. He doesn’t know what to do, and now he’s going to do something fucking insane and try to kill a monster in the woods because there’s nothing else in the world he can do. And that is a piece. The one that actually is a little different is Department of Truth. That has the most conventional hook with a twist at the end.

That ends with Lee Harvey Oswald, right?

James: Yes, exactly. Department of Truth lays everything out. In terms of the economy of storytelling, it’s probably the one that…it tells you the most about the book in the book. And it starts with the scene of Lee Harvey Oswald taken from newsreel footage of Lee Harvey Oswald. So it starts in the real world, and it is a kind of scritchy Xerox of a Xerox feel of something that’s actual newsreel footage. And then it goes deep into weird conspiracy, and then it slams into the present and you don’t understand who these characters are or why this person’s being interrogated. And then through the telling of the story, you also get the central conceit of Department of Truth, that every issue is going to dig into a real world conspiracy and explain a bit of the history of that conspiracy theory through the context of this world.

And then you get the giant question mark of the woman in red, The Fictional Woman, with Xes for eyes. And then at the very end, you get the big hook of…Lee Harvey Oswald was there in the beginning. He’s here now. He’s running the Department of Truth. This kid is deep in over his head, but you understand exactly what the entire book is. The tone of the book. Martin’s art from page one tells you exactly what the book’s going to feel like. That one tells you exactly what it is. And before you get the final hook, Department of Truth tells you the high concept of the world, that it’s consensus-based reality. And it fully explains, this is the premise, and then here’s the reason you should keep reading.

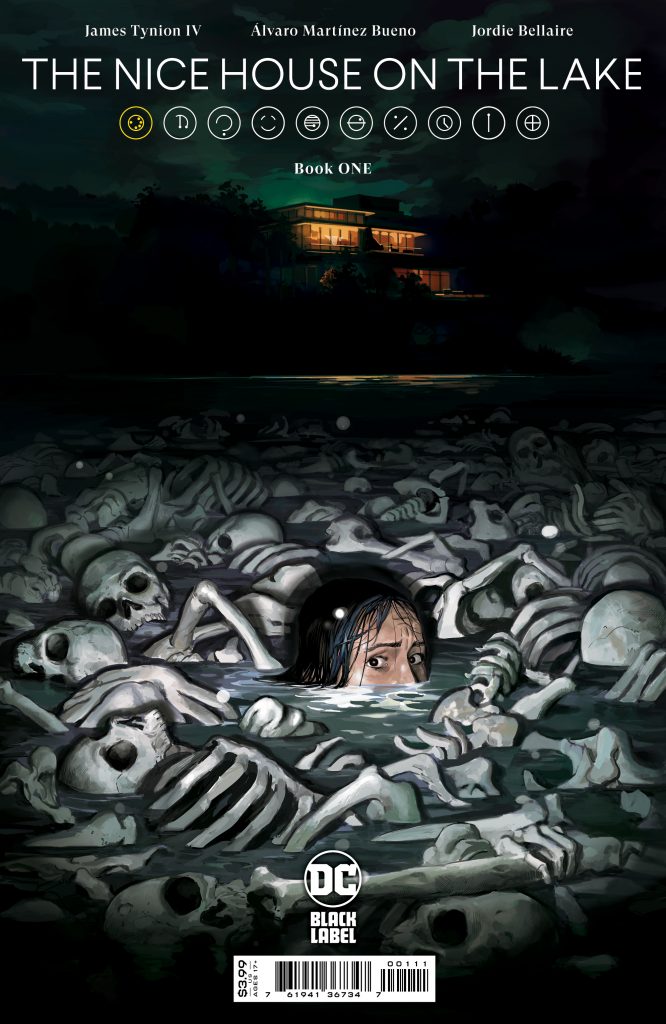

Nice House is character driven. Most of the issues of Nice House are just people arriving at a house and talking to each other. I really struggled with how to start that book for a really long time because the original one-page pitch of Nice House is basically everything that happens in the first issue up to the end, but it didn’t have the opener. So I was like, “How do I open this book?” And it was similar to what I was saying with Wynd, where I knew where this ended, but I needed the feeling of the apocalypse from page one. That’s where we created that kind of the feel of this future, this flash forward. And then we have Ryan speaking directly to the camera.

And what I was trying to evoke there is that I re-watched Scorsese’s Cape Fear. It’s only a few sentences long, but that movie starts with Juliette Lewis just speaking directly to the camera from the end of the story. And it is just like that, and it is just so powerful and emotional. And so in those first four pages, which then became the standard for how I structured the book moving forward, you understand that the entire series hinges on the relationship between these characters and Walter, and how that relationship involves the end of the world. And then you do the slow build, you introduce all the characters, you introduce the setting, you introduce the weird tensions of it all, and then you see it’s the end of the world.

You see that Walter is part of what has ended the world, and you see that. And then he says he loves them all and vanishes, leaving them all lingering there. And the last page is fully silent. It isn’t like a loud twist ending. We linger in the tension. The final shot is just lingering in the, “Holy fuck,” tension of it all. And that was very deliberate.

I don’t think (Nice House on the Lake editor) Chris Conroy got a vote because it was probably too early for him, but if he did, I would side with him. Nice House is my favorite of your first issues.

James: I agree.

I think that w0rldtr33 does similar things in the sense that it establishes the idea of what’s going on. It doesn’t give us all the details of it. It establishes the world and the rules and the parameters, and it leaves enough to mystery that you’re like, “I have to know more. I have to know what’s going on with these people and what’s going on with this Walter guy and everything like that.”

I mean, similarly, the interesting thing is from a convention standpoint, Department of Truth is more conventional, but it’s also not that different from what I’m talking about though. Lee Harvey Oswald is a pretty big question mark to leave on, even though it in itself is an answer to who is this guy? Because you’re like, “Who is this guy?” And then you’re like, “Wait, he’s Lee Harvey Oswald?”! It’s answering a question with a question.

James: It immediately asked the question of, “Is the Department of Truth the good guys?” Because what we know from history, Lee Harvey Oswald isn’t a good guy. So the answer to, “Who is this?” is one of the most notorious figures in history, and he’s running the department that’s deciding what’s true or not. It’s meant to create a tension immediately.

I think it’s interesting because I mentioned hooks and final pages, but the hook doesn’t always have to be the final page. The hook just has to give you enough questions that you want answered to keep you going.

James: Fair.

And I think you did a pretty good job of that.

James: I appreciate that.

You’ve talked about this before, even especially in relationship to my work, but the best number ones in the game are written by Brian K. Vaughan. Y: The Last Man, Saga, and Paper Girls are functionally perfect first issues, and they all have a loud hook as the final page. I don’t always hit it at the final page. Sometimes I hit it a few beats before the final page and all of that. But in writing all of these issues, I revisited those three issues so many times to pick them apart and see how they worked. They each work in different ways. Ex Machina is actually right up there, obviously as a very loud final page.

That’s the blueprint of how to write a good issue number one. And those are all character driven stories, but they all have very high concepts. They linger along enough with the characters that you really get a sense of their voices. You get a sense of why you’re going to enjoy spending time with them. You get a sense of the personality of the book. The artist gets to show off what they do well in it. And that’s the other really important thing.

The art side of this is just fundamental. It shows off the artist, it shows off the high concept, it shows off the characters. All of those things are what you need to get a reader to come back. And in all of those cases, the readers came back.

Well, and that goes back to something else you said earlier, which is the importance of the key image. Visuals are an essential part of this, and part of the reason why w0rldtr33 and Nice House, for example, have that big, “What the fuck. I have to keep going. That moment when Walter’s attacked and you find out what he is and you know what he is not us, and then with w0rldtr33, there are multiple parts but the freakout scene at the end when PH34R goes up to Gibson Lane and shows him the Undernet, and he’s just broken as a person…the way that Fernando and Jordie make that page come to life, it gets in under your skin, just like the Undernet does with Gibson. That’s really important.

James: Those are the moments that announced that they’re science fiction stories.

Before that, is this just a grounded story? No, this is a genre piece, but it is all rooted very much in the real world. And I think that is another thing that is a central priority in each of my comics of the current generation. I’m not trying to create a different world. I want to start from the world we live in. And I think that’s just a preference.

And honestly, it’s probably reactionary to 10 years of doing DC superhero comics. I don’t want to build a whole extra world. I want to use the shorthand of the real world and the way that people talk to each other in the real world. I want these relationships to feel like relationships feel today in the here and now, and then here’s the high concept element.

The real world grounding in a lot of ways is the reason why the sci-fi stuff works as well as it does for me. They kind of set each other off. And the funny thing about Nice House is a lot of the stuff that I liked the most was just them trying to figure out this world and everything.

Like David, the Comedian, he spends an entire issue just being a goofball and ordering Ferris Bueller’s outfit and wearing it around and doing all this random stuff. But then at the end, it turns into this really intense thing that has this science fiction feel to it. And the reason why that last beat works is because of that grounding. And now I’m talking about issue number four, I think it was. So I’m going way off. But at the same time, I do think that that grounding really matters.

James: You have to do the work in issue one to get you there. And it is funny in talking about all of this, and now thinking back to specifically these four issues, they all do kind of announce their genre elements at the exact same point in the story. We don’t see the monster in Something Is Killing the Children until a few pages before the end of the issue. That’s roughly the same point that Walter’s revealed. That’s the same point that you see that there is something really science fiction-y going on when Gibson glitches out of phase with our reality, and then in Department of Truth, that’s when we see the literal ice wall at the end of the world. And you understand that this isn’t just a political conspiracy book. We are doing something weirder.

I guess that is a very me thing.

So you looked at Brian K Vaughan’s books and you’re like, “Wait, what if we did this three pages earlier?”

James: Yeah.

Take that, Brian.

James: Brian, actually in all cases, announces the genre elements much earlier.

Oh yeah.

James: You know Ex Machina is a superhero book very early on, superhero with the modern political side. You understand that in the first few pages. You see the first time traveler before you understand it’s time travel fairly early into Paper Girls.

People start dying.

James: Yeah, people start dying in Y. And then Saga, obviously it’s a space opera from page one.

I actually thought about mentioning Brian multiple times in this chat and I’m like, “I can’t keep repeating this beat.” I feel like I bring up Brian K. Vaughan every time we talk.

James: It’s real. I’m not shying away from the fact that BKV is a big influence on me.

If you had to pick one, which of your number ones do you think you were most successful with?

James: I think all four of those, the four main ones that we’ve been talking about, I think all four of them succeeded. And there are things that I like about each success that sticks with me.

Right now, I’m very happy with w0rldtr33 because it is the one that…I mean, it’s the one I wrote most recently. But it’s also the one that I explained the least of what the high concept of that series is in the first issue, but it still delivered the result I wanted it to, which I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to pull off.

But I will say out of those four titles, what Nice House was trying to sell was a more complicated, weird idea…I know it has a very singular high concept, but it was just the process of selling the end of the world in the pages we had to do it and then establishing that larger cast in the pages we had to do it in…I still look back at that and it was definitely one of the most difficult. Once I was in a flow, I fell into it. I had to find my way in, which is usually how I write. Once I actually start writing. I write very quickly.

Each of these other core comics, I understood before it came out why and how it’s going to sell. Nice House was the one that I was worried because it’s the most personal to me. Obviously I’ve talked about how Walter is just me and that a lot of these characters are based on my close friends, but it’s the one that I’m asking people to read a long form series about people in a static setting that they’re stuck in. And it was like, “Are people going to just want to read characters talking to each other in a house? In a comic book?” And thankfully, the answer is yes.

The other ones have clearer hooks. Something is Killing the Children and w0rldtr33, both have cool-looking murder ladies in them. That’s a good selling point, bar all else. And then on top of that, Department of Truth, if you’re fascinated in conspiracy culture and the history of conspiracy theories, if you’ve ever had any interest in any of that kind of esoteric history, you will find an issue or two of that book that you will like.

But Nice House on the Lake, the core of why I’m writing that book is me working through my emotions and the central piece of it is just people talking in a house. So the fact that we pulled off a first issue that made everyone come back, it feels like a feat in a different way.