Does Continuity Matter Anymore? [Poll]

We talk about the impact continuity has on comics today and ask readers to take a poll on the subject

I’m not sure if you’ve noticed, but lately, there has been a lot of upheaval in Marvel and DC’s publishing lines. Even for them, both houses are making desperate attempts at gaining readers outside their usual purviews while revitalizing interest within their own readership.

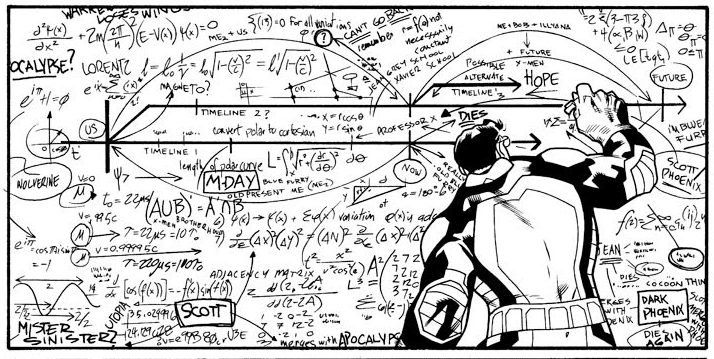

It starts at the House of Ideas with Secret Wars in full swing. That book is a mega event from the team of Jonathan Hickman and Esad Ribic that brings Hickman’s three year run on the Avengers books to a head, but its big change has more to do with what comes next. All-New, All-Different Marvel is springing from that story in September. it’s promising all new #1’s for Marvel’s entire line, possibly eclipsing 60 debuts in a single process. New volumes means more jumping on points, right?

Meanwhile DC just wrapped Convergence, a two month event that opened the DC Universe back up to being a Multiverse like it once was. The idea behind that one was – at least in part – to simplify everything by taking away the rules that once governed the New 52. The questions of “did this happen? or “did that happen?” are still there. But in a way everything happened now. It’s just they all happened in different universes.

Each move is related to continuity and Marvel and DC’s continued attempts to distance themselves from it to a degree. While Marvel’s move is a more overt try to make its books more inclusive and to free its line from shackles of continuity without a complete reset, they both are a shift in the way these two companies approach stories. While not a whole lot has changed or will change after each of those stories, the question is one that’s more about approach. From what was shown, the new books that have (or will) come from these events are built to be easier to digest. Instead of being enslaved to decades of history, these new directions give readers as fresh of a start as you can get without a brand new universe behind them.

It’s a change from what we’ve seen in the past, as once upon a time, continuity was a feature of Marvel and DC comics. Not a potential barrier to entry for new readers. With Marvel and DC working overtime to court new and lapsed readers instead of trying to hold on to the last remnants of a once great society of comic fans, a question has been circling in my head a lot lately.

Does continuity really matter anymore?

It depends on who you ask. To the publishers? It depends on what will make them more money this year, I imagine. For the editors at Marvel and DC? Definitely. A part of their job is acting as internal checks and balances on what is consistent with a character or a story and what isn’t, so that will always be a part of what they do. Creators? As Jaime Weinman noted in a recent (and excellent) piece at MacLean’s on the subject of continuity, most of them would be happier if it was just gone for good. But do readers ever care about continuity as we once did? That’s the interesting question, as while we didn’t create continuity, it’s our obsession over it that led to it being as intertwined with the stories of the Big Two as it did.

For me, it depends. When I was a kid, I loved continuity. It was fun latching onto the world of the X-Men and attempting to figure out things like the Summers’ family tree (always evolving, that) and what Wolverine’s backstory was before it was clarified in Origin. It’s the same reason why Lost was so popular. The disparate relationships and complicated histories weren’t confusing, they were the foundation of my interest in these worlds. How could the Onslaught storyline mean the world to me – let alone make sense – if I didn’t have an informal PHd in X-Menology?

As I’ve aged, though, continuity has lost its appeal. Part of that is because I stopped reading comics for several years in the early 2000’s and fell out of touch with many of my favorite titles then. But even when I came back into comics, I found myself getting involved with the same obsession with canon I had in the past before eventually burning out. Thankfully, in this era of comics even Marvel and DC had options for readers like me.

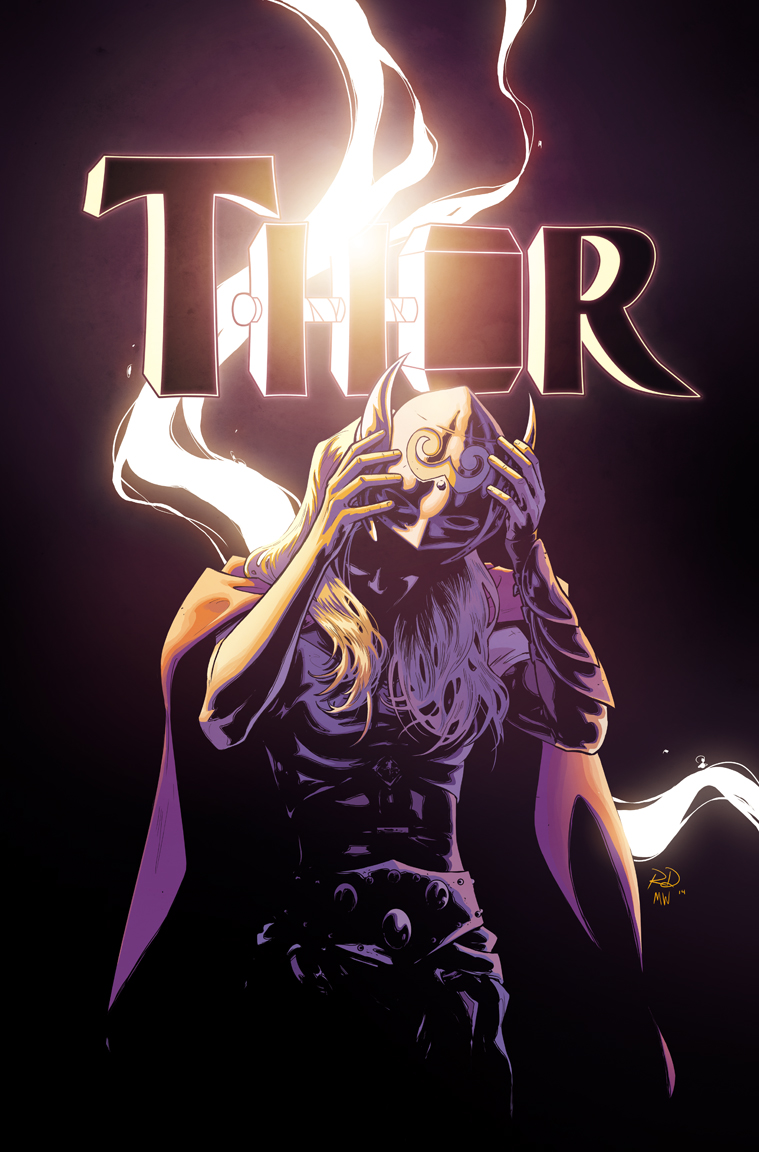

At both houses these days, I gravitate more towards the stories that are self-contained. The ones that build their own worlds without being slaves to the stories around them. Books such as Charles Soule and Javier Pulido’s She-Hulk, G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona’s Ms. Marvel, Becky Cloonan, Brenden Fletcher and Karl Kerschl’s Gotham Academy, and Jason Aaron, Esad Ribic and Russell Dauterman’s work on Thor have been favorites of mine in recent years. That’s at least partially because they’re beholden to no story but their own. There are intermittent references here or simple nods there, but as texture, not as a defining characteristic.

At both houses these days, I gravitate more towards the stories that are self-contained. The ones that build their own worlds without being slaves to the stories around them. Books such as Charles Soule and Javier Pulido’s She-Hulk, G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona’s Ms. Marvel, Becky Cloonan, Brenden Fletcher and Karl Kerschl’s Gotham Academy, and Jason Aaron, Esad Ribic and Russell Dauterman’s work on Thor have been favorites of mine in recent years. That’s at least partially because they’re beholden to no story but their own. There are intermittent references here or simple nods there, but as texture, not as a defining characteristic.

Even flagship books like Hickman’s Avengers comics work outside of continuity in their own way. As Weinman said in his piece, “(Hickman’s) Avengers run, for better or for worse, has less to do with the history of the team than any other run; he has said it’s about ‘aggressively going forward,’ not backward, so all you really need to know is that the Avengers are a big super team and Iron Man is kind of a jerk.” Secret Wars itself builds from Hickman’s internal continuity he’s developed in his Avengers books rather than any previous history. It spends most of its time dissolving the known continuity we expect from Marvel books to make way for its own, as if Hickman’s the Marvel equivalent of Tyler Durden. It’s only after comics have lost everything that they’re free to do anything.

And that I can support. At this point, I prefer my comics to be sans continuity, save for whatever mechanics the storytellers need to keep consistency within their own work. If I had my druthers, Marvel and DC’s comics would take a different approach to their stories. They’d follow the paths of books like Young Avengers, the recent Moon Knight volume or the last two volumes of Hawkeye, as those three books have very interesting recent publishing histories that might be worth emulating.

Young Avengers always was more of a seasonal book, as creative teams come on, tell their story and leave. Same with Moon Knight, except the teams all exist within the same volume, just rotating on and off every six issues or so. Hawkeye changed volumes, creative teams and style entirely when Matt Fraction and David Aja left and Jeff Lemire and Ramon Perez launched All-New Hawkeye. Lemire and Perez kept some of what the earlier team did but weren’t beholden to it, instead diving off into their own exciting directions.

All three books are easy to jump into. You can pick up single collections and not feel lost if you didn’t read everything that preceded it, and they’re all good. They’re not steeped in the stories of the past, instead being allowed to tell the stories they want without constantly thinking about what a character said that one time a few years ago and whether or not this fighting style is consistent with the character from earlier runs. It’s refreshing, and I wish we saw more standalone stories like that.

I’ve been saying this for years, but I’d love to see the bigger publishers do away with the perpetually serialized issue counts for good. Instead, every book would exist in seasons like TV shows. 12 issue, self-contained runs featuring one creative team, and after that ends, another comes on. There would be carry over from volume to volume, but they wouldn’t be the basis of the story. They’d be what I said earlier – texture. I would be all about that, and to their credit, Marvel has said that the idea of “seasons” is something they’re embracing in their All-New, All-Different era.

But you know where I stand. My question is to you – the readers. What’s your take? Does continuity matter to you anymore? Answer the poll below – please expand on your answer if you like – and I’ll share the results this Friday right here on SKTCHD.

Create your own user feedback survey

Art from Secret Wars by Alex Ross, from All-New X-Men by Stuart Immonen and Wade Von Grawbadger and from Thor #8 by Russell Dauterman and Matt Wilson.