Revisitor: The Universal and Timeless Power of Nick Abadzis’ Laika

Revisitor is a regular column in which I look back on personal favorites of mine from comic history, whether they’re a single issue, graphic novel, comic strip, webcomic or basically any form of sequential art you can think of. When I do this, my hope is to include perspective from the people who made these comics – like I did with the debut edition about Mike Mignola’s Hellboy story, “Pancakes” – but that may not always happen. This week’s edition does feature the creator, however, as I look at the early First Second release Laika from cartoonist Nick Abadzis.

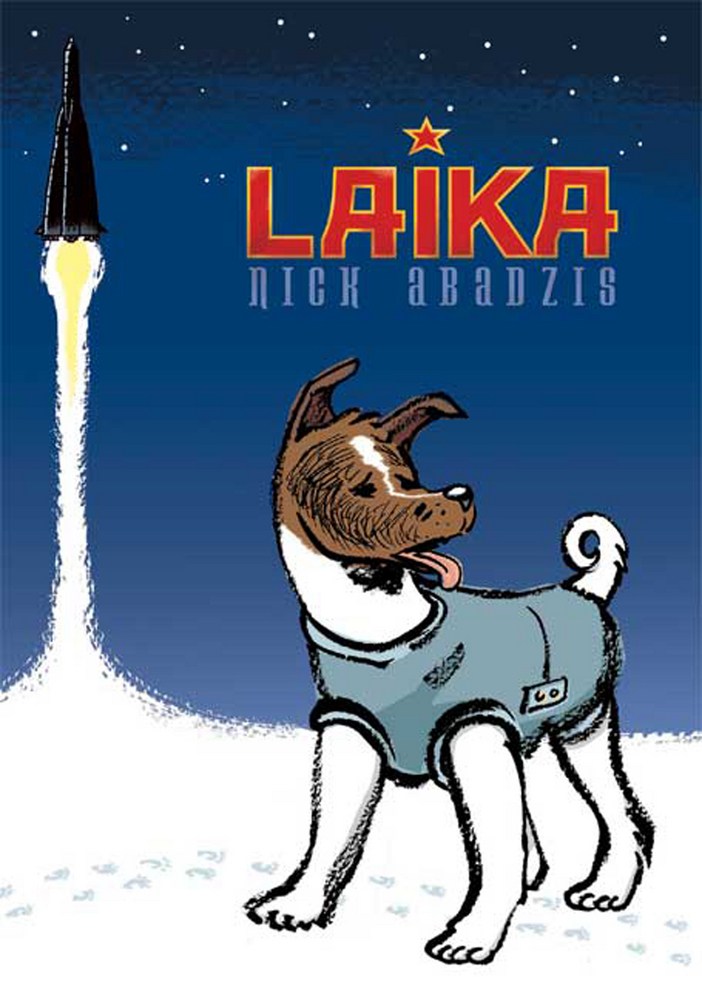

There’s no comic I’ve shared more with friends and family than Nick Abadzis’ 2007 graphic novel Laika. It tells the story of Kudryavka, also known as Laika, the famous cosmodog who became the first animal to ever orbit the Earth in 1957. To say it’s a remarkable and emotional read doesn’t really do it justice. Consider this: I’ve never loaned it to someone without them returning it and saying something along the lines of, “This made me cry so much,” or, perhaps even more impressively, “I didn’t know comics could be like this.” It doesn’t just affect people; it wrecks them. Not only that, but to my non-comics reading friends, it’s a perfect gateway to understanding the capability of comics as an artform.

There are a slew of reasons for that. It helps quite a bit that Laika is a remarkably well-researched work – the depths of which Abadzis details in this interview with Tom Spurgeon – even if some elements of it are artful fiction built off a foundation of what we do know about its realities. The potency of this story and its world wouldn’t be the same without the insight into its cast of very real characters it gives us. Space Race-era Russia was a time of tenuous freedoms and iron clad beliefs in the veracity of this country, much of which was built on a distorted version of reality. People like lead Soviet rocket engineer Sergei Korolev and Oleg Gazenko, the man who guided the program that provided animals for the country’s efforts in space, were featured prominently within this graphic novel, and their presence helps introduce, deliver and contextualize this story. That Abadzis went above and beyond to represent them and the rest of this world with as much truth as possible gives it the weight it has. It was essential.

Of course, Abadzis is also a remarkable cartoonist. His lyrical approach imbues Laika with emotional heft and an uncanny beauty that it needed to hit readers hard. His gift for story flow allowed it to be a propulsive read as well, and one that is impossible to put down until it’s complete. His art is a perfect example of the blurred line in comics between writing and visuals, and how both are storytelling even if many don’t often believe that when it comes down to attribution. Each expression, each person’s posture, each panel layout choice is designed to connect us more deeply with everything we read, even if we’re reading nothing but pictures. But that’s what comics are, or at least should be.

In short, Laika finds a cartoonist at the peak of his powers telling a tale that’s universal in an unexpected way. Of course, you might be wondering “What’s universally appealing about historical fiction set in Russia in the 1950s?”

That it’s about a dog rather than a person.

I know that’s a wild oversimplification about a wondrous, complex graphic novel – it’s much more than a cute animal comic – but hear me out! Human characters we can take or leave, but animals or – more specifically – dogs? There’s an inherent protectiveness we develop for them if they’re prominently featured. It’s a part of the reason John Wick became such a sensation or why that forgettable Idris Elba/Kate Winslet film The Mountain Between Us said in its trailers that the dog didn’t die during it. 1 Not everyone likes every person, but the percentage of dogs we don’t like – save for people with allergies or those who hate dogs, which is criminal and minimal – is considerably lower. That’s a not inconsiderable reason this comic was so easy to hand off to people and for them to jump onboard. Stories in which dogs are put into jeopardy fuel a bond with most, and one that’s unbreakably strong for everyone but the most heartless of individuals.

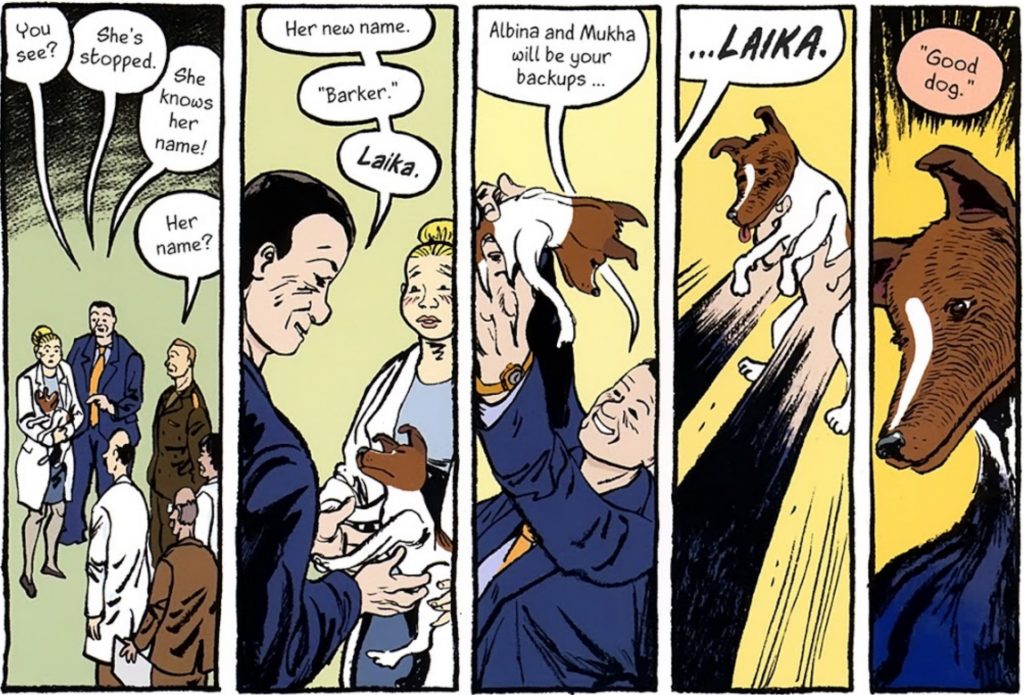

And there’s no animal in the history of the Earth that was put into a more famously perilous position than Kudryavka, the innocent, three-year-old mixed breed dog more famously known as Laika. 2 She was, again, the first lifeform who orbited the Earth, having been sent into space with no hope of return ostensibly for research but really as a public relations tactic in 1957. She was once a little, forgotten stray on the streets of Moscow, but because of her sacrifice, Abadzis told me that, “She’s become a legend – part myth, but all truth.”

While this entire graphic novel is brilliant, its effectiveness relied upon Abadzis connecting readers with Laika herself. That is what I’m focusing on today. It’d be tough sledding to make us care about this story and the historic figures within its pages without believably attaching us as readers to the wonder dog at its core. That’s where the weight of the story lies and the emotional investment that could make or break the book is built. Thankfully, and perhaps obviously, Abadzis nailed it.

And he likely did so because of the significant care and consideration that went into his approach to the character. You can’t just throw an animal in your story and it’s immediately a success. It takes a well thought out approach and deliberate choices, as there are multiple ways you can handle them. While some stories can try and connect us with animals by anthropomorphizing them – building a link by making them seem more like humans, i.e. making them able to talk or at least have a voice – and potentially losing what it is we love about them to begin with, Abadzis went the opposite route with Laika.

“What I wanted to do was keep Kudryavka’s canine qualities intact so that the reader didn’t suddenly get a sense of some authorial narrative interference,” Abadzis said. “It was crucial that the human characters, many of whom are real historical figures and whose attitudes to the dogs were thoroughly researched, are seen to treat the cosmodogs like they would real animals; their behavior had to be believable.

“In doing that, you leave a bit more room for the reader’s own empathy to engage. Hopefully, the relationship you strike up with the reader is that you get them thinking and recognizing how they’d treat one of these dogs. In all my work, I strive to make the world within the pages immersive, as real to the reader as possible.”

He was successful with Laika, perfectly connecting readers with the emotions he was hoping to deliver. And it was because he never tried to make her something she wasn’t. Throughout the story, Kudryavka develops relationships with an array of people, with some being deserved – the little girl and her mother who originally have her; Mistress Yelena, her caretaker who is closest to her; even Vladimir Yazdovsky, the Russian scientist who took the dog home to spend the evening with his children so she could “play like an ordinary dog for once” before she was taken to the launch site, from which she’d never return 3 – or some not, like the boy that was forced to adopt her, was unkind because of that, yet earned the love of the dog all the same. By portraying her as an animal that held no cruelty for anyone and just wanted love like any dog might, Abadzis forged a bridge to readers emotionally, bonding us to this story in the process. 4

Of course, it might be easy to just make a dog seem like a dog. But fostering a connection to readers takes more than that. We had to almost place ourselves in the story. Abadzis relied on those aforementioned relationships to do this.

“I was quite careful…to show Kudryavka (AKA Laika)’s emotions via her handlers – via Korolev, Yelena, Gazenko, Yazdovsky,” Abadzis told me. “It had to be via their responses to her as much as just trying to evolve a sort of canine shorthand that seemed believable without resorting to anything too tricksy or that drew attention to itself.”

That careful balance worked in two ways. Obviously it helped develop our bond with Laika herself. But it was also essential to make readers see more in the human cast, whom on the surface could seem like villains for cursing this sweet dog to an awful ending if Abadzis hadn’t delivered any emotional context.

“I think it was also important for the reader to see that the people who were Laika’s handlers weren’t monsters; they weren’t necessarily uncaring or deliberately callous towards their charges,” Abadzis said. “Like the dog herself, they were part of a giant political system that demanded certain behaviors from them that they felt duty-bound to carry out.” 5

That’s shown in a quote from Gazenko himself that Abadzis includes after the main narrative ends. It underlines the inescapable emotions Laika left in those who came into contact with her.

“Work with animals is a source of suffering to all of us. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog.”

— Oleg Gazenko, the former director of the Institute of Biomedical Problems in Moscow

Abadzis suggests that this is indicative of how “those scientists and kennel keepers were very well aware of the emotions of the dogs they looked after,” and it’s hard to disagree with him. That’s something he taps into within the story through a variety of techniques. While Abadzis doesn’t go as far as making Laika and her fellow cosmodogs speak like a regular character, he does give us some views into the internal life of these animals, all of which enriches the story and our relationship with them.

Some of it is simple, like imagined interactions Mistress Yelena has with Laika and her peers as she cares for them. It’s all messages of their desired freedom or a life outside of the machine they’re a part of, and it’s believable both in how Abadzis handles the beats visually and from a written standpoint. You think an imaginary conversation between a dog and a Russian scientist isn’t going to hit you hard, but then you see how Abadzis draws subtle emotion into the dog’s face and you’re like, “Oh great, I’m crying again. Thanks Nick!” These do wonders for not just making the dogs feel more real, but also for building empathy with Yelena and the rest of the cast.

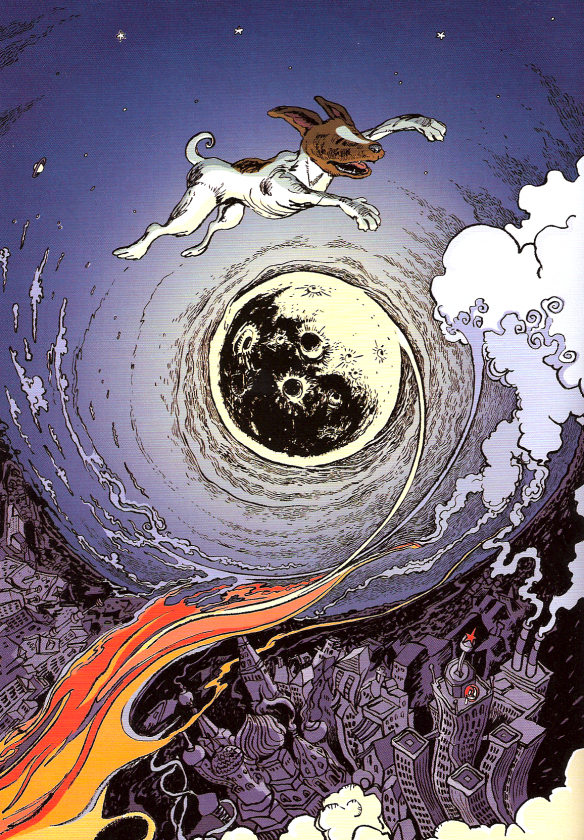

But then there are the dream sequences Laika has on occasion, in which she imagines herself flying, looking down on the world and those she loves. They’re beautiful moments, and ones that forecast her eventual fate even if it’s not quite as cheerful in the end. Throughout the book, including in these sequences and in the opening and close of the story, Abadzis wanted to connect readers through these parallels, allowing “for a bit of authorial commentary albeit disguised in dramatic terms.” He was successful in that endeavor.

“I worked hard to give a sense of balance to the book, an idea that there’s a circularity and inevitability to some events due to human behavior. There are deliberate echoes of that throughout the book,” Abadzis said of moments like Laika’s flights that were only in dreams.

These echoes can be as simple as Laika’s recurring dreams of flight, or they can be as emotionally devastating as the parallels of Liliana – the little girl who loved Laika most but was never given another chance to see her once the dog went under state control – and Yelena, a character who thematically “is a grown-up version of Liliana.” These two characters were the ones most invested in Laika living a good life. In the conclusion, we’re given more than a thematic connection as the two meet on the street.

“That’s why they encounter each other at the end, and the reader realizes that they’re neighbors and knew each other all along,” Abadzis said. “That’s the joke of fate.”

Laika was loved by that young girl and her older proxy of a sort, and she is loved by many even today. A huge part of that lasting memory and even the potency of this book is tied to her unfair fate as part of a game she was never meant to be a part of. Worldwide and even in Russia, it’s shown that after Laika dies on her journey, this craven effort to curry favor in the Motherland faced a backlash. There’s even a conversation between Gazenko and Yazdovsky where they discuss how they would have preferred a person being sent up on this suicide mission in Laika’s place. I asked Abadzis about that, and why sacrificing a dog left such an open wound in a way even a human’s death wouldn’t have been. His answer was spot on.

“Because she was an innocent,” he said. “She wasn’t asked if she wanted to make the journey and there was no-one to speak for her – or no-one that could, not even Korolev, not Yazdovsky certainly not Gazenko, or Yelena.

“In many ways they were as trapped and as powerless as the dog was.”

That innocence is a massive part of why this comic is so heartbreaking, and also why another interesting phenomenon hits you throughout your read. As you read it – even if you’ve read it before! even if you know the story intimately from being a history buff! even if you just know the fate that awaits this sweet dog! – you always root for a different result, a splintering in the path that takes us to another, better world where Kudryavka was given the life she deserves with one of the people who loved her. You want a happy ending, even if her fate was sealed over sixty years ago. This was an animal that was wronged for little payoff, and because of that, you find yourself wanting to change her fate in a way that’s obviously impossible.

But it isn’t entirely if you’re a storyteller like Abadzis, who was given an opportunity to do just that when he was approached by the comic shop chain Big Planet Comics to create new endings for Laika as part of the shop’s 25th anniversary. He leapt at the opportunity, saying “You could riff on the idea of Laika forever, because she’s such a huge part of worldwide folklore now.” Each comic depicted a different, happier, and sometimes genuinely strange alternate ending to the story, all of which feature Laika surviving in the end in some way, shape or form. Abadzis loved having the chance to tackle this project, suggesting he “very easily could’ve done a hundred or so of those.” They also gave a respite of sorts to those who wished for a different fate for Laika.

“They’re offered as an interlude or epilogue of sorts, a salve for those who find the truth of the ending difficult to take,” Abadzis told me.

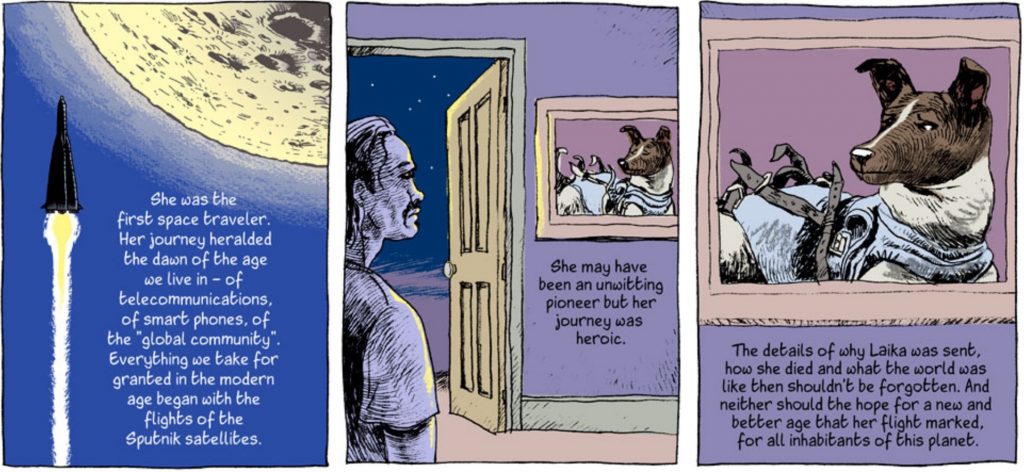

Amongst the five comics Abadzis created for this endeavor, he shared that the fifth of them – in which he tells the story of why he made the comic itself and looks at the lasting impact of this wonder dog – had to be the final one. It’s a perfect coda to the graphic novel, a heartbreaking yet poignant read in its own right. When I asked him about these comics, his thoughts on that fifth comic and its message – which he reiterated to me – showcased why that was.

“You can’t change history, not one line. Laika died, she was a sacrificial passenger on a voyage that was largely a publicity stunt. People – myself included – wanted her to live, for that act of cruelty not to have occurred. But it did. I mean, I wanted her to live so much that I wrote a book about why she died and how that came to be, and how all the human beings around her had to go along with it because the machine of their society dictated that this event had to happen.

“To an extent, we’re all embedded in a social system whose rules we obey, whether consciously or unconsciously and while we might think that we here in the west in the 21st century have more freedoms than those in 1950s Russia did, I think we have to be careful about being too kneejerk in our responses to what surrounds us, especially with the rise of social media. If this book is ‘about’ anything, it’s a plea to be mindful, self-aware of the choices one faces in any day-to-day situation and how that might affect others, especially, in this case, those with no voices. We all need to be heard, but we could also all learn to listen more. Observe more, react less, or give ourselves time to make more considered reactions.

“But, above all, listen better.”

While this comic – and beyond that, this story – became such a notable work and such an easy graphic novel for me to hand to friends to enjoy at least in part because of our natural empathy for dogs, 6 it’s much more than that. Laika, both the comic and the dog herself, live as exemplars of the importance of what Abadzis said there. The tragic destiny of this animal is something we as a society will hopefully never forget, and not just because she was a dog and who doesn’t love dogs? We shouldn’t because the cruelty of her plight doesn’t reside in her species but in her position as the voiceless, someone left to an undeserved fate simply because we didn’t consider how our desires affected those around us.

Perhaps that’s where the true universality of the story lies. Who hasn’t had a time where we’ve felt like cogs in a machine, left behind by the choices others make for us? Laika reminds us that our choices affect more than just ourselves and the immediate world around us, whether you’re talking about people you might not typically consider or a little dog just looking to love and be loved. In that way, it reaches a timelessness that escapes the confines of typical historical fiction, becoming something more – part myth, but all truth, like its titular character – in the process.

Thanks to Abadzis for looking back on this graphic novel with me. You can find him on his website, Twitter and Instagram. Also, you should really read Laika.

They were so concerned about people turning away from the movie out of fear that the dog would die that they literally spoiled their own movie to assuage fears. It didn’t help.↩

Kudryavka was the original name of Laika, a name given to her in the narrative because she was rather vocal nature at the time. While she was notably mild-mannered amongst those that knew her, she became Laika – aka “the barker” in Russian – when she wouldn’t stop barking when Korolev met her.↩

Full disclosure: typing that sentence nearly made me cry. This book is a problem.↩

In an early version, Abadzis actually did consider having Laika be able to speak. But he quickly abandoned it. As he shared, “It would’ve been so easy to have Laika narrate her own voyage – but I think you’d completely lose the drama and the potential emotional truth of her situation if you did that.”↩

This is most effectively showcased in the parallel lives of Korolev and Laika, as they’re the only two characters who appear throughout the whole graphic novel as well as the ones whose existences mirrored each other the most, down to how the Russian machine chewed them up and spit them both out.↩

And everything else I mentioned, of course.↩