The Rise of Webtoon

On the stunning success of the digital comics giant and what's leading the way for the platform.

Who are the most successful publishers in comics?

When you ponder that question, I’m sure plenty of names pop into your brain, with your answer largely depending on which variables you’re looking at. If you lean towards the American direct market, you’re thinking Marvel or DC. If you’re talking about the book market, it has to be Scholastic or Viz. If we’re getting international, you might favor Shueisha 1 or Glénat. All worthy choices. But the point is, there are plenty of options to choose from.

There’s one that many sleep on, though, which is wild because they might be more highly read than any of them. It’s a publishing house that does numbers most only dream of with an audience some can’t seem to connect with. We’re talking 15 million readers daily, 100 billion views annually, and 55 million users every month in 60 countries, with roughly 65% of those readers being women. And that’s just the English version of the platform, which has only existed since 2014. 2 You may have figured out who I’m talking about based off the metrics I used.

I’m talking about Webtoon.

Perhaps more commonly known as LINE Webtoon, 3 this primarily app-based comics portal is owned by Korean search engine supergiant Naver and powered by a legion of passionate creators. The platform is both free and, crucially, easy to use. To read comics on Webtoon, 4 just go to their website or download the app and get started. It’s that simple, as Women Write About Comics’ critic Claire Napier told me.

“To experience the joy of serial comics, all a kid has to do now is pick up their phone,” Napier shared. “That’s so safe and stress-free that it’s honestly a revelation.”

From a usability standpoint, it is incomprehensibly simple compared to how everything else in comics works. They’ve gotten everything down to a science, as you download the app, answer a series of questions, and then they fine tune the experience based off your answers. They deliver the comics they believe you’d enjoy in a personalized experience, which makes sorting through Webtoon’s one million webcomics 5 that much easier. It’s an astonishingly modern and frictionless reading experience for a comic platform, and certainly beyond compare in that regard. And from a creator standpoint, it might be even more idyllic, offering a rare mix of freedom, potential for success, and creative challenges that might be impossible to beat.

When you add it all up, you start to consider a different question: is Webtoon the most important platform for comics, period? It’s a fair to wonder, even just on the surface. The numbers it does, the experience it offers, the promise it gives creators…those are incredible differentiators. But as with everything, there’s always more to the story when you dig a bit deeper, even if it ends up being more of the same. This is an exploration of what makes Webtoon what it is through the stories of three key creators, and how a platform you may not have even heard of might have cracked the comic code by playing a completely different game altogether.

Cartoonist Dean Haspiel has always been an advocate of digital comics, embracing the nascent concept in varying forms for years and years. As someone who created or worked with gone-but-not-forgotten digital platforms like ACT-I-VATE and Zuda, Haspiel saw the value, even if it was borne from pragmatism.

“I think part of what it truly was, was that I probably wasn’t good enough to get published by Marvel and DC when I was younger because my artwork wasn’t up to snuff or because maybe my ideas weren’t as commercial,” Haspiel told me about his affinity for webcomics. “I realized that I needed to carve my own path.”

Haspiel spent years cultivating his skills on those aforementioned platforms and beyond, as well as on projects outside of comics, including an Emmy win for his main title design to the HBO series Bored to Death. But he always had love for digital comics. So when former Webtoon content editor Tom Akel asked Haspiel to pitch him something as part of an effort the publisher was putting together to draw American readers to the platform via Western-favored creators, 6 he was naturally intrigued.

“I thought, ‘Well, that’s really cool,’” Haspiel said.

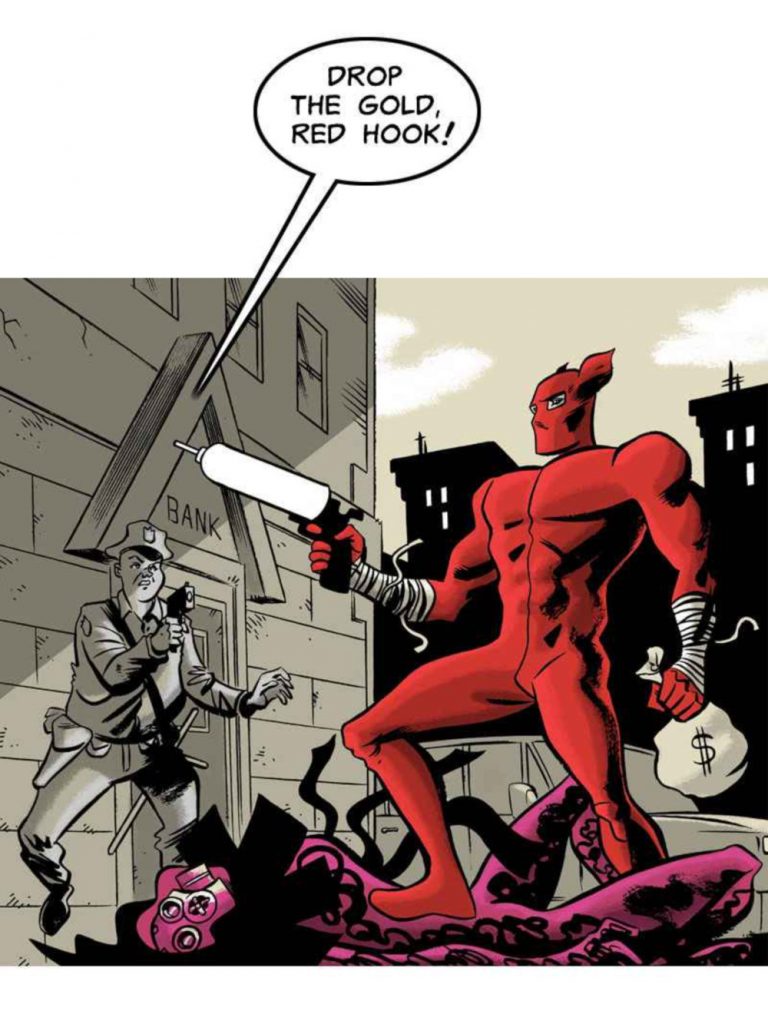

The cartoonist was onboard, leading to the creation of Haspiel’s world of New Brooklyn and a trio of titles 7 called The Red Hook, War Cry and STARCROSS. His experience highlights one of the key themes of Webtoon’s platform: freedom, in all senses of the word. We’ll start with the freedom it offers creators, though.

Haspiel’s comics are not what you’d normally expect on the platform. As he admits to me, he’s “a guy that comes from old school superhero comics,” which isn’t what the average Webtoon reader – an audience that skews very young and, as noted before, towards women – are traditionally believed to desire. And yet, the publisher supports Haspiel in his efforts regardless, as the cartoonist told me “what’s great is that I’m doing a different kind of thing and they’re letting me do it.”

“I mean, in other words, there’s no one telling me what to do,” he added. 8

Haspiel has free reign to do what he does, and his editors support him despite the awkward conceptual fit. Now I know what you might be thinking: he’s a guy they recruited for a specific purpose, so they need him to do what he does to attract certain readers. And while that may be true, other creators I spoke to found equal amounts of freedom without those same parameters.

Take Lore Olympus’ creator Rachel Smythe, for example. When I asked her about the appeal of the digital giant, Smythe told me, “I like Webtoon because they essentially just let you do your thing,” especially when compared to others she tried to work with. When trying to get into the print industry before, she said there was “no way anyone would take (her) seriously” and that emailing her portfolio to editors was “pretty much the same as throwing it into a bin.” She would earn comments about how unsophisticated her art was or how it was too sexualized in an unappealing way. Now, after utilizing the freedom Webtoon offered her, I could make a pretty convincing argument that Smythe is one of the most successful comic creators on the planet.

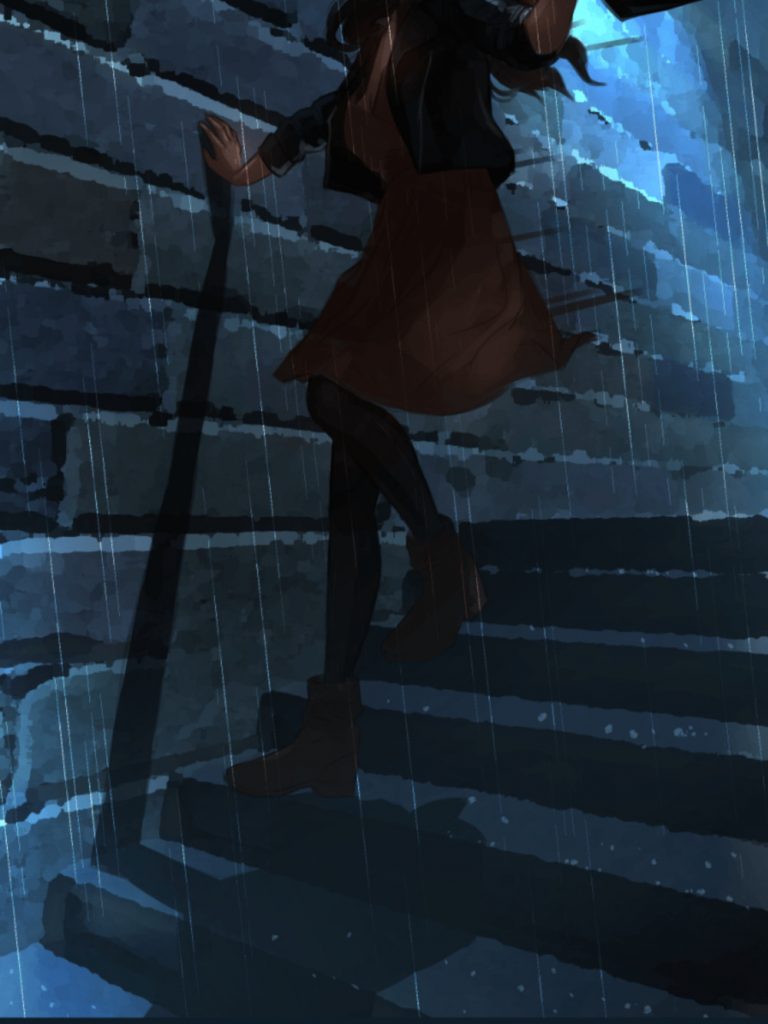

Smythe’s comic is a romantic retelling of the Greek myth of Persephone, and the cartoonist believed “people who enjoy romance want to read comics.” According to Smythe, Webtoon understood that while also allowing her to do what she needed to do to make Lore Olympus work.

“I just feel there’s no other place that would accept that’s the way it is. They’d just be like, ‘No, this isn’t right. That’s not right. And do it different,’ all the time.” Smythe told me. “But Webtoon just lets me do it.”

That’s part of what makes Webtoon such a fascinating platform. No single genre dominates its efforts like superheroes do in the direct market, as its leading story categories are romance, 9 drama, fantasy and slice of life. That’s reflective of a portal that’s welcoming to people of all varieties, whether you’re talking readers or creators. While it’s commonly discussed that around 65% of Webtoon’s readers are women, there’s a comparable split on the creative side of the equation as well, with 65 to 70% of Webtoon creators being women, 10 per Webtoon’s former Head of Publicity Kim Estlund. 11 There’s also a very active LGTBQIA+ community, with many of the comics reflecting that both in their actual and desired ships. Webtoon thrives in the areas comics just aren’t supposed to work in, and that is a key driver of its success.

That creative freedom manifests itself on the art side as well, with an incredibly diverse mix of styles, even if the manga influence is present throughout. You can find shōjo manga stylings on titles like Mongie’s Let’s Play, painterly works like Yaromary’s CAVEAT, comic strips-meet-memes visuals in Hey Bob Guy’s Amor E Morte, Kirby-influenced work in Haspiel’s The Red Hook, more traditional Western looks in Fabian Nicieza and Reilly Brown’s Outrage, and…whatever you’d classify Smythe’s gorgeous, dreamy work as in Lore Olympus. The list could go on and on and on. Part of this is an extension of the volume of comics Webtoon publishes, with the aforementioned one million webcomics residing on the platform, a truly unreal number. That’s due to the YouTube-like equal opportunity they provide with Canvas, the purely user generated side of comic creation on Webtoon.

Here’s how it works. There’s Originals, which are the comics Webtoon pays people to publish on the platform. And then there’s Canvas, 12 the comics creators publish to gain an audience and potentially earn a cut of ad revenue 13 or even graduate to Originals status. If you’d like more detail on how these differentiate from each other, I’d recommend reading this explainer Sakurada Yana created on their slice of life series My Weird Roommate, as it expertly walks readers through the difference. But the point is this: Canvas generates a ton of content, which ensures plenty of diversity in style and creators. It’s extremely welcoming to a broad mix of ideas and perspectives.

Another type of freedom Webtoon offers comes from their honestly unbelievable creator deal for Originals. Here’s the gist of how it works, just in a general sense. When an Originals creator signs up, they’re promising to create a season of their comic, for which they’re given a page rate. 14 Once they’ve completed said season, there is an exclusivity window Webtoon has with the comic. But the creator owns their comic in totality – or at least in the cases of the creators I spoke to – so once that exclusivity ends, they can do whatever they want with it. Haspiel did just that with The Red Hook.

“I have the latitude and the ability to take this thing that, again, I own, that I’m basically licensing to Webtoon, and broker a deal with Image to be able to publish this about a year later,” Haspiel told me.

Haspiel was paid a page rate for The Red Hook by Webtoon, then was able to publish a print version at Image, 15 and eventually he’ll even be able to put it up on ComiXology, or so Haspiel believes. Plus, he owns it in full.

“I’m getting paid to write and draw something that I own and meanwhile you can read it for free,” Haspiel said to me, somewhat incredulously.

It’s like he’s able to have his cake and eat it too, but then have seconds and thirds and beyond. Of course, there are requirements of the deal, as each creator must produce a certain amount of panels per chapter of their comic each week. But with decent lead time and ingenuity, it can be done.

The last type of freedom I wanted to note before moving on is the most basic form of the word: Webtoon is straight up free for people to use. Haspiel loves that aspect because when people ask what he does, he can tell them that he’s a cartoonist and that his “comic is in (their) pocket right now for free.”

“I think that they’ve made it very easy for anybody to enjoy a variety of comics,” Haspiel added. “Not only do they have the variety, but it’s in your pocket on your phone. You press your thumb a couple of times and you’re scrolling through a comic. What else can you ask for?”

Napier described its price point of nothing to me as Webtoon’s “most attractive” differentiator, saying, “You just download an app and can immediately read chapters and chapters of every single title they host.”

“It’s a smorgasbord.”

“I found Webtoon by accident,” Smythe told me. “I think it had a bunch of horror comics that I was reading at the time. And I didn’t understand the platform. I was like, ‘I don’t get it, but there’s a lot of comics here and they seem to update on a weekly basis.’

“And I was like, ‘Perhaps I could do this also.’”

That’s the basics of how Lore Olympus – a comic with 3.4 million subscribers and 1.4 million weekly readers, which are just stupid numbers really – got started as a comic. Contrary to the belief of some commenters, though, Smythe’s myth-based romance series wasn’t an overnight success. The cartoonist described it as “a bit of a dark horse.”

While she went to school for computer graphics and design, her 20s were a mix of retail and graphic design jobs with art and the occasional webcomic mixed in for fun. Her first effort at Webtoon was purely an exercise in learning, as The Doctor Foxglove Show was her attempt to figure out a platform she was struggling to understand. But when she hit a milestone in her life, she wanted a project to do, so she decided to really give it a go with a comic at the digital giant.

“I turned 30 and I was like, ‘What are you going to do? Are you going to make a thing or not? Make a thing, just do it. It’s fine.’” Smythe said.

Make a thing she did, with Lore Olympus starting out as a Canvas title with steady growth, especially after it was featured in Webtoon’s weekly round-up at the bottom of the publisher’s site.

“The truth is for the most part, every day I think it’s going to dip and it’s going to stop,” Smythe said about the title’s success. “But from that point onward of having that little primer on the bottom of that page, which I believe was in June of 2017, it’s always gone upwards.

“It’s just never stopped.”

Smythe’s story is a perfect example of the potential for success – the second theme we’ll be focusing on – Webtoon has for creators and as a platform unto itself. I already highlighted the numbers the comic does – 3.4 million subscribers is a number many would trade very important things for, like first born children or souls 16 – but what you might not know is what that kind of thing means for the creators themselves. There’s a tangible impact here.

Take Smythe and Lore Olympus’ graduation from Canvas to Originals, an event that came at the end of 2017. With support from the publisher both financially and creatively, 17 Smythe started the comic over 18 and rebuilt it in an attempt to make it even better. She was uncertain how it would go, so Smythe kept her day job in the process out of fear the bottom could fall out. Instead, it kept building and building and building, leading to the cartoonist departing her day job around chapter 18.

It was Smythe’s analytical nature and desire to emphasize the things that people connect with that fueled its rise, at least in part, with the comic hitting the top spot of Webtoon’s rankings midway through 2019 and effectively taking residence there ever since.

So what does that mean for a creator like Smythe? Consider the Webtoon deal again. Originals creators earn a page rate, which Estlund described as “comparable with what you would make” at DC or Marvel as a freelancer, with it certainly fluctuating depending on the deal. Another element Webtoon offers readers is an almost video game mechanic called “Fast Pass” that allows readers to access the next episodes of a comic before anyone else if they pay a few “coins,” 19 which creators get a cut of. Between the strictly Webtoon-driven elements, Estlund suggested that several top creators are earning more than $10,000 a month. When you think about the Patreon integration the publisher includes – Smythe uses that to the tune of 11,645 patrons, which earns them access to a Discord server for the comic and behind the scenes content – and the fact that, oh yeah, these creators retain the rights to the comic to later publish in print if they so desire, your brain starts to dizzy about the upper limits of success Webtoon offers.

“You’re getting paid the one time as the creators,” Haspiel said. “And if it does really, really well and gets a lot of hits, you get in on some of that gravy, right?”

Mongie, the creator of Let’s Play, tapped into this by creating a Kickstarter campaign for a print collection of the first volume of her “romance in the gaming world” comic. Her goal was $10,000 to print and distribute the book. It generated $233,750, which, by my estimation, is a lot of gravy.

Smythe’s version of that story was a deal with The Jim Henson Company to turn Lore Olympus into an animated series, an idea that thrills her. The cartoonist loves Jim Henson and described the deal as a match made in heaven for her. It’s part of a storm of success she has seen thanks to publishing that comic through Webtoon, with her telling me with a somewhat bewildered lilt, “this is a comic I started off for funsies a couple of years ago and hopefully now it’s going to be a TV show.”

Much of this stems from the growth of the Lore Olympus community, which is an essential part of how Webtoon hits become what they are. These people aren’t just fans; they seemingly feel like they’re a part of something larger. You can see it when you browse the comments for any of the big titles, as it’s clear that these readers aren’t just clicking on a comic and disappearing, but talking with each other and celebrating something they love. 20 That’s something Napier agreed with.

“I think that the comment section is also a plus,” Napier said. “People really do like to be able to chat about their entertainment.”

Smythe described Lore Olympus as having a “really big fan community” 21 and views that as a big part of her success. That’s most clearly represented on her aforementioned Discord 22 with over 10,000 members calling it home. That alone is almost like a full-time job – she has help within the community, but she said she feels like she could have “a whole community manager” just for that side of things – but it’s worth it for how it generates excitement and camaraderie amongst fans.

“When you have people hanging out with each other, it elevates the enthusiasm if people have other people to talk to about the whole thing,” Smythe said. “Those people really help and I don’t think I would be where I am today without the community, for sure.”

This is where being free plays a part as well. That enthusiasm is cultivated thanks to access. Anyone can read these comics, and because of the excitement they feel for their favorite works, fans feel the need to support the work voluntarily via Patreon and other platforms. From a creator side, there’s a very grassroots-like nature to it, but with a rather significant wrinkle. It’s like if your grassroots campaign was delivered on a platform with millions of daily users and the guidance of personalization algorithms based off a quiz you yourself took. So it’s grassroots, but on steroids.

That personalization effort was something Webtoon put into the app experience last year while they were rolling out a significant advertising campaign as they wanted to ensure new users could find comics that fit them. It works incredibly well, leading me to a fun mix of titles. It’s simple and straightforward, just like the rest of the platform, as Napier shared.

“Mechanics wise, it’s just so easy,” Napier said. “Minimal clicking. Next chapter button right there are the bottom of the one you just read. Series listed by successfulness, by today’s release, by genre… banner adds at the top of the homepage offering new series to try.”

Napier compares it to walking in through a door while “other comic hubs make me come in and out through the window,” and the shoe fits. It’s remarkable how easy to jump in and keep going it is, as you read an episode of a Webtoon in the app and all you have to do is swipe up and the next one will load. It’s like Netflix autoloading another episode once one is complete. “I might as well read another,” you think as you instinctively swipe upwards, leaning into the binge experience so many crave these days.

Because of that ease of use and how Webtoon cultivates the community feel – Napier specifically cited “reading challenges” the publisher puts on, and how they “actually make reading series you haven’t tried before seem rewarding” as one way they do that 23 – you can see how audiences for comics can build quickly. Webtoon’s a data driven company, and per Estlund, they use that information to give prospects on both the Canvas and Originals side of the equation a push when needed. That’s all great for growing usage within the app experience, of course. But what about generating new users? That’s why Webtoon put together a multi-million dollar advertising campaign across varying platforms – TV, digital, social, billboards, etc. – last year to develop its audience, something that’s basically never done in comics, as Estlund noted.

It worked, as the publisher went from 10 million readers per day to 15 over that span, Estlund shared. I know people who joined up because of that effort, as a good friend of my wife signed up because of an ad she was served on Instagram. 24 She had never really read comics before. Now? She’s a regular reader of multiple titles on Webtoon, including Lore Olympus.

Much of the success of the platform – and something that fits the story of my wife’s friend – is how Webtoon delivers content that appeals to woefully underserved audiences.

“Webtoon is where comics are ‘for’ teenage girls,” Napier told me. “That’s not even reduced to uncool teenage girls, or nerdy teenage girls, or weird teenage girls—it’s visually driven, chatty teenage girls, on Snapchat and Instagram and probably places I have failed to notice.”

“There’s no loss of quality average when compared to other readership hubs, and centering on a recently very underserved demographic isn’t a reductive choice in terms of depth, subject, intensity, genre, etc; it’s simply, really, an aesthetic one,” Napier added. “You can see that there are plenty of stories with elements that teen girls are often belittled or dismissed for enjoying, and that those stories are extremely popular.

“It’s easy to see that they’re supported by the platform and the company, and the people who run the official social accounts.”

And it does so using a mechanic that speaks to this underserved audience: mobile phones. Webtoon is entirely built around the mobile experience, and the importance of that cannot be understated. There’s the old saying of you have to fish where the fish are, and 81% of Americans have smartphones, per Pew. It’s where they are, it’s what they do – eMarketer says smart phone users spend three hours and ten minutes a day on their phones – and because of that, it’s the right place to deliver comics. That’s foundational to Webtoon’s success.

In general, Webtoon can be a supercharger for creators…but only if it hits. With a million webcomics, give or take some small or large number, competition can be fierce. And when Canvas operates off a structure that pays creators a share of ad revenue once they hit certain thresholds, there are likely far more creators who earn little to nothing than there are big successes. That can be problematic, ensuring significant effort with little return. It can turn creators off of the platform, sending them to competitors like Tapas. Webtoon only requires exclusivity of platform for Originals creators, and Estlund suggested that creators choose to stick to Canvas so they can leverage other platforms at the same time. They’d rather “diversify their portfolios” to increase potential earnings, Estlund told me.

That’s why titles being elevated from Canvas to Originals is such a desired result and such a point of consternation for the creative community: it’s effectively elevating creators to a better life, straight away. Estlund said Canvas creators get frustrated when something they believe is of a lower quality is lifted, but it’s something the publisher does with great care.

The formula for graduation from one to another is more complicated than just skimming the cream from the top. Estlund said “plenty” of Canvas titles that became Originals had “very low numbers,” but there was something someone saw in the title that suggested there was untapped potential there. It’s sort of like the Super Soldier Serum: moving up to Originals amplifies what’s already there. It’s rarely something as simple as straight readership driving those decisions.

Artist Reilly Brown is a veteran of both print and digital comics, working on Marvel titles like Deadpool and having once produced a creator-owned comic for ComiXology called Power Play with writer Kurt Christenson. But digital just speaks to him, in particular.

“There’s something uniquely enjoyable about working in newer formats where there is still room to explore and innovate new things,” Brown told me. “The thing I particularly like about working in digital platforms is the potential to reach a larger audience, and especially a younger audience, because younger people interact with the world almost entirely through their phones.”

Brown shared a studio with Haspiel when the latter first joined Webtoon, so he was familiar with the platform and its benefits. When the publisher was again looking for established Marvel and DC creators, Haspiel introduced Brown and his collaborator – writer Fabian Nicieza – to the team over there so they could chat about an idea the pair had. It was called Outrage, a superhero action comedy about a “virus attacking people who abuse others on the internet.” It was a natural fit with the platform given the social media-fueled nature of the story in Brown’s mind. Webtoon agreed, and the title became a success.

The tricky part about Brown’s experience taps into the third element of Webtoon’s secret sauce, and that’s the creative side of fusing comics with the mobile experience. Webtoon may not have invented the idea of vertical scroll comics that play off the use of smart phones, 25 but they’ve been one of the most successful at utilizing the format. And for someone coming from traditional comics like Brown, that means relearning the wheel to a degree.

“There was definitely a learning curve,” Brown told me. “The biggest differences were the small size of the screen, as well as the vertical orientation of their app, and also, with the way that the comic scrolls, which means that the artist doesn’t have as much control over what the reader is seeing on screen.”

“The act of scrolling itself is a part of the reading experience, and that was tough to really figure out how to make the most of,” Brown added. “But once you figure that out, it goes pretty smoothly.”

Haspiel was impressed by how quickly his former studio mate learned to leverage the strengths and mitigate the weaknesses of this format. Brown was a natural with it in a way few Western creators who were hired from traditional comics have been. As Haspiel said, the vertical scroll of Webtoon comics changes “the way you have to think about pacing narratively” with no page turns being factored in.

In a way, the difference between vertical scroll comics and traditional comics is like the difference between Catalan and Spanish. Many of the same roots are there, but there are enough differences to puzzle anyone who is fluent in one but not the other. That’s why Brown is a bit of an anomaly in how quick he figured it out. The most successful creators in the format tend to be the ones who create for that format primarily, as you can feel how differently they pace things. Take Lore Olympus, for example. Smythe is masterful in how she delivers information and paces the read. You can tell she’s designed it specifically with the mobile read in mind.

The cartoonist didn’t get there in a day either – just like the format didn’t, as she noted, as you really needed the right technology and quality of internet to make the vertical scroll an enjoyable experience – but once she did, she was cooking. It’s all in her mindset.

“Comics (are) about revealing information frame by frame,” Smythe said. “I think it really helps with that…the visual surprise that you’re getting.”

This different format allows for a wide mix of how creators choose to deliver information, whether it’s Haspiel and his print-first focus that he almost retrofits onto Webtoon by using tall panels, 66’s incredibly smooth flow in City of Blank, Yaongyi’s usage of social media visuals in True Beauty, Mongie and her blending of traditional panels and legions of negative space, Brown and his endlessly waterfalling narrative, or any number of other approaches. The vertical scroll allows for a seemingly unlimited amount of variations of how these stories can be told, meaning that no two comics are really all that similar.

That’s the fascinating thing. The vertical scroll might seem inherently restrictive from a comic creation standpoint, but to me, a user of Webtoon, it seems almost infinitely flexible. Wally Wood would definitely have to update his rubric because of the options it presents, as there are way more than 22 panels that always work here. 26 It’s an incredibly malleable version of the comic form, and as a longtime reader of the medium, hopping on Webtoon and seeing what the kids are coming up with these days is an endlessly thrilling experience. The inventiveness seen on both Canvas and Originals is mind-boggling, and it leads to a platform that truly has something for anyone, I imagine.

Of course, it’s a lot of work as well. Smythe publishes Lore Olympus weekly, and she describes it as “hard sometimes” but “very rewarding” as well. As noted earlier, creators have basically unlimited creative freedom, and as someone who writes and draws her own comic, Smythe is well aware that “there’s not a lot of creative opportunities like that in the universe.”

Her process for crafting each chapter of Lore Olympus starts with writing the script over a weekend, then drafting it out with the help of her assistants. The ability to have an assistant is a godsend for her, as Smythe noted, “if I just did absolutely every single aspect of the comic, I think my wrist would drop off.” Sometime in the future, though, the comic is going to reach the conclusion of its first season, at which point there will be a break, allowing the cartoonist to “build up more of a buffer than I currently have.”

As she mentioned to me, though, that’s a privileged position she’s in. Very few cartoonists have that kind of good fortune, arguably especially on Webtoon. That’s a weakness of the platform, in Napier’s mind.

“It seems that the cartoonists who are successful there are still often overworked,” Napier said. “I haven’t heard anyone say they are being overworked by Webtoon but it is common to see notes that make it clear the cartoonists are overworking themselves in order to stay afloat on this platform, which is a responsibility of the company to mitigate.”

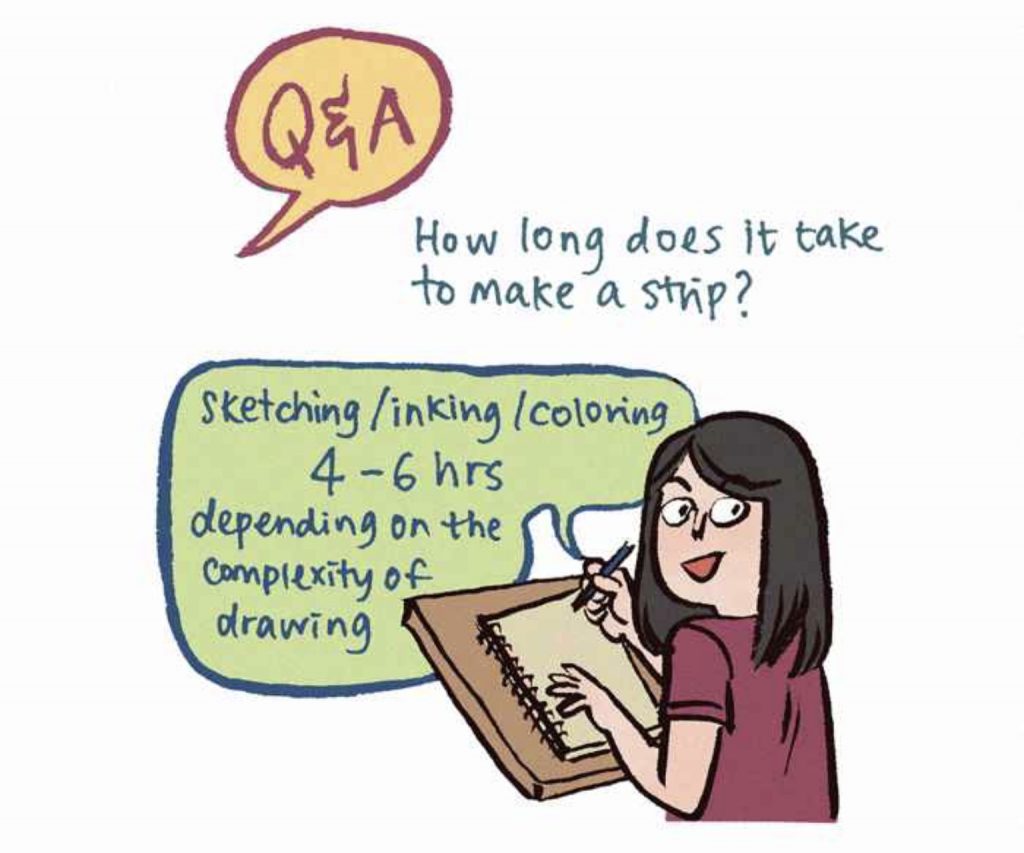

This manifests itself in creators sharing notes in chapters saying they had to make a shorter episode or include a Q&A or something else to pad the space, per Napier. When you combine that with the incredibly competitive environment they’re all taking part in, it can lead to overworked creatives who are earning little for their production. Napier said that those notes from creators aren’t necessarily bad, as they “educate the audience about what it takes to produce the content which they are considering paying for.” But it does show her that “Webtoon isn’t the panacea that has stopped comics production from ever being a fun ride to poverty or death.”

I first started paying attention to Webtoon for a rather bizarre reason. Back in September 2019, a collection of articles appeared on varying comic sites touting Webtoon and its accomplishments to an almost euphoric degree. I was suspicious. They were so positive that they almost had to be advertorials. 27 So I started researching the platform, trying to figure out what was up with it. In the process, my tune changed. 28

The part I came around on was the messaging: Webtoon genuinely seems to be this good.

While I’ve laid out the downsides of the platform above – overworked creators, naturally underpaid Canvas creators, the volume of comics making success on the lowest levels incredibly difficult, as well as a mention Napier had about the occasional poor English translation – the biggest problem I have with Webtoon as a whole is there’s an almost inescapable feeling of “this has to be too good to be true, right?” While Webtoon itself is the Platonic ideal of a modern comic company, leveraging technology and modern trends to ignite interest in comics, it’s still funded by Korea’s largest search engine. Tech companies are inherently fluid in approach, and if the numbers ever don’t add up, perhaps they could bounce altogether. Estlund told me that the company only recently started making revenue, so you could see a path with statements like that being made.

But that idea is one I had to hypothesize, brewed up because I could see few other problems. It seems to be working for readers, creators, and the publisher itself, delivering freedom, success and creative opportunity for all. It’s such a phenomenon, Napier wonders why we others don’t emulate the idea.

“I don’t see why every publisher doesn’t have their own Webtoon-like platform, offering their content in exactly the same way,” Napier shared.

The obvious answer is twofold: one, most comic companies aren’t funded by Korea’s answer to Google, and two, comic publishers, like most companies, extremely love money. But you can see the benefits to Napier’s idea, especially if you’re a Marvel or a DC, whose value really lies in intellectual property as much as anything. Building excitement and passion for those worlds and characters so you turn millions in the box office into billions seems like a smart play. Risky, maybe. But potentially smart.

Ultimately, though, the most important part of Webtoon has little to do with the three themes I mentioned. I’m sorry to say that, thousands of words in, but it’s true. It’s actually something else that was discussed earlier. It’s this: Webtoon is important because it’s not for me, a 36-year-old white guy who is used to going to comic shops each week, or other readers like me. Of course, it isn’t not for me – I enjoy a lot of comics on Webtoon – but the success of Webtoon has been primarily generated because it looked at young women and said, “you deserve comics too, and not just the ones we think you want.” It’s become an almost unlimited resource of stories that are rarely available in Western comics, like Let’s Play and its shōjo manga-like feel 29 or Lore Olympus and its vibrant romance.

All of this makes Webtoon something that’s deeply important to the future of comics: the natural follower to the manga boom of the 2000s and a potential next step for Raina Telgemeier fans looking for something new. Those are woefully underserved audiences as they age, and this provides them an outlet as they transition to stories outside of the ones they discovered the medium with. There are few things more important in comics than finding that next step, and Webtoon might be at least part of the answer to a very important question: “what’s next?”

Brown has seen that, and it’s something that’s shaping his view of comics as he goes to conventions and realizes the fans generated by his work in the direct market are the same age as him or older. It was “a scary thought” to him when he thought of the future of his career.

“We’re in a climate where the direct market comic publishers are worried about a dwindling audience, while they keep rebooting properties from 20 years ago, meanwhile you have Webtoon where they have comics with brand new concepts with over a million subscribers every week,” Brown said. “There are plenty of comics readers out there, you just have to figure out how to reach them, and Webtoon is doing that better than anyone.”

“Right now, I think Webtoon is the The Thing,” he added. “Whatever the X-Men was in the 90s, or Manga was in the 00s, that’s what Webtoon is now. They’re the thing that the people who work in the comics industry in ten to twenty years will have come up reading, and what got them into comics.”

“So, whatever Webtoon is, I’m glad to be a part of it.”

That’s a good point by Brown. It’s hard to say exactly what Webtoon is. Is it a tech company? Is it a publisher? Is it a comic-sharing platform? All of those answers are true, but none of them are exactly correct. To me, the answer is something perhaps unnecessarily grandiose, but fitting all the same: Webtoon is the first truly modern comics publisher. Let’s hope they’re the first of many, because comics would be all the better for it.

Thanks for reading this feature on SKTCHD! This site is a subscription-based one, and if you’d like to read more comics journalism like this feature, maybe consider subscribing!

The publisher of Weekly Shōnen Jump and the owner of Viz.↩

There are also Spanish, Korean, Japanese, French, and Chinese (in multiple dialects) versions, at least.↩

It seems they’ve moved on from the LINE aspect of the name recently, but I can’t find any real confirmation of that.↩

Quick note: while digital comics in general from South Korea are known as webtoons, I will specifically be talking about the company Webtoon here.↩

!!!!!!!!!!!↩

This included creators like Warren Ellis, Colleen Doran, and even Stan Lee, amongst others.↩

To date, as Haspiel told me he’s working on a fourth already and is hoping for six ultimately.↩

Save for one sex scene, in which they asked him to cover it up a little bit.↩

It’s number one with a bullet.↩

Many of whom use pseudonyms to great success, choosing to let the work speak for itself.↩

Major shouts to Estlund, by the way. She’s one of the most enthusiastic and eager PR/marketing people I’ve ever worked with in comics, and her unexpected departure from the company came at the tail end of this article’s development.↩

Which was originally known as Discover.↩

More on that later.↩

More on that later as well.↩

Which was effectively given free advertising by Webtoon in the process!↩

And it’s impressive even if the comic is free.↩

Originals get editors.↩

Which is apparently a common thing for those who graduate.↩

Which equates to real money, of course.↩

My favorite quirk from Webtoon’s comments: how excited people are when they have a top comment on an episode. People are genuinely hyped about it, and it’s honestly adorable.↩

Just search Lore Olympus on Twitter if you don’t believe me. Cosplayers and fan art galore!↩

Which, in case you don’t know, is effectively text and voice software that also has forum-like functionality. That’s what Smythe uses it for.↩

Which is a fantastic idea.↩

Bonus point: Webtoon’s social game is strong in general, as Napier highlights in her “bimonthlyish” column at Women Write About Comics, “Insta Made Me Read It.”↩

Good luck figuring out who did, because I certainly couldn’t!↩

Including using no panels!↩

Advertisements designed as editorials, in case you aren’t fluent in adspeak.↩

Not about the advertorials of course, as I’d wager some of those were part of the marketing campaign the publisher took on.↩

I love it because it reminds me of Netflix’s totally wild adaptation of the shōjo manga series Good Morning Call, an all-timer guilty pleasure for me.↩