Celebrating the Thrill of the Mundane in Paul Pope’s 100%

I had bought the t-shirt before everything went to shit. It was one of the shirts created by Rock Roll Repeat to celebrate Image Comics’ new remastered edition of Paul Pope’s 100%, a white tee with a close-up of two people kissing on the front. It was my second piece of Pope apparel after I scored a hoodie he created for DKNY back in 2008 that I still have today, and I had big plans for it. I was going to wear my new t-shirt out to Boystown, hit the local go-go bar with my friends, get very drunk, and eventually lose myself on a dance floor, where I would ideally recreate the image on my clothes with a random stranger. I’d be possessed by the spirit of Pope’s comic and transcend my lowly reality on a wave of lights, sounds, and writhing, sweating bodies, feeling in reality all the sensations that Pope so powerfully captures on the page.

The shirt arrived three weeks into quarantine. Boystown was and still is dark, except for a few essential businesses and restaurants that are still taking carry-out and delivery orders. The concepts of social distancing and nightlife are fundamentally at odds; I have no idea if the go-go bar will survive or what dance floors will even look like after the pandemic. In this new world, 100% becomes an escapist fantasy not because of its sci-fi trappings, but because it takes place in bars and clubs and has characters engaging with live art.

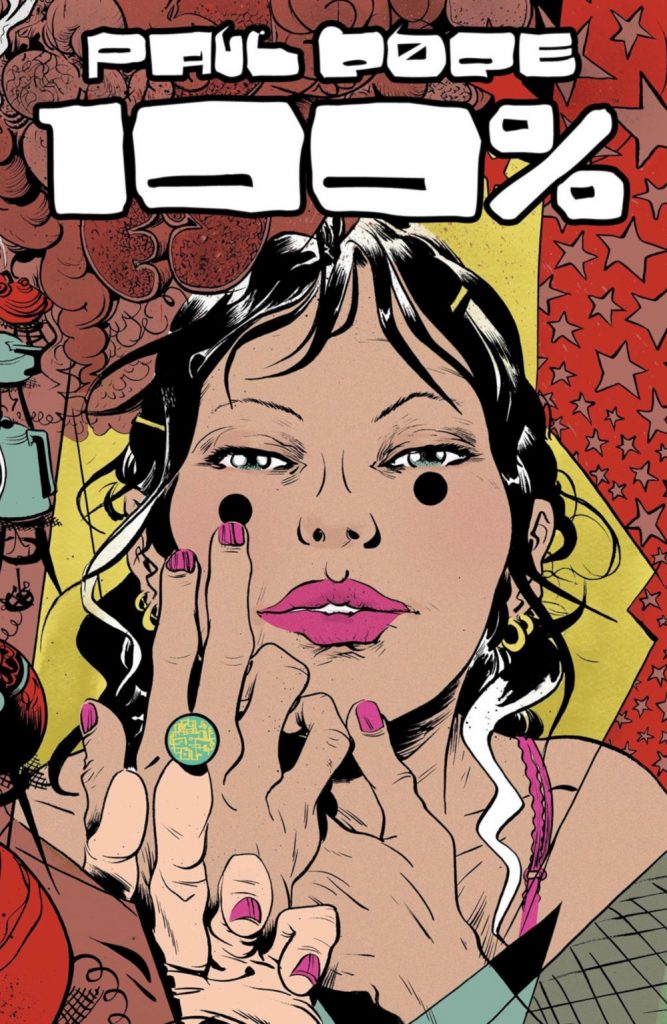

Originally published as a five-issue miniseries by Vertigo Comics in 2002, 100% follows three couples in a futuristic New York City, the same setting as Pope’s Heavy Liquid. The mundane nature of Pope’s story has always been its greatest strength, and despite its cyberpunk sci-fi elements, 100% steers away from heightened action and intrigue. It’s a story about ordinary people trying to survive in the city, experiencing passion, affection, and pain in the process.

Strip club busboy John is enamored with the new dancer, Daisy, an international drifter who may or may not have survived a devastating childhood trauma. Strel manages the dancers at the Cathouse while raising a young son, and she has to choose whether or not she’s going to take back her estranged prizefighter husband, Haitous, who suddenly reappears in her life. Bartender Kim falls hard for Strel’s artist cousin, Eloy, and she doesn’t want him to compromise his creative vision in his search for funding. There are flying police cars and “four-dee” virtual reality restaurants, but ultimately 100% is grounded in relatable personal relationships challenged by romantic, creative, and professional pressures.

Revisiting 100% over the years has really highlighted how circumstances shape the art we consume. The last time I read 100%, I was about a year out of college, serving tables and writing reviews while pursuing a short-lived acting career. My first time was in high school, when I found a copy of the collection at my local library. On that first read, 100% was a full-on fantasy, taking a sheltered, closeted teenage boy to a forbidden megalopolis where people smoked weed cigarettes and strippers virtually exposed their guts to dancing crowds. That world didn’t seem so far away when I read 100% after college, and experiencing the thrilling chaos of city life for myself took away some of the story’s mystique, replacing it with emotional gravitas as I gained a deeper connection to the characters.

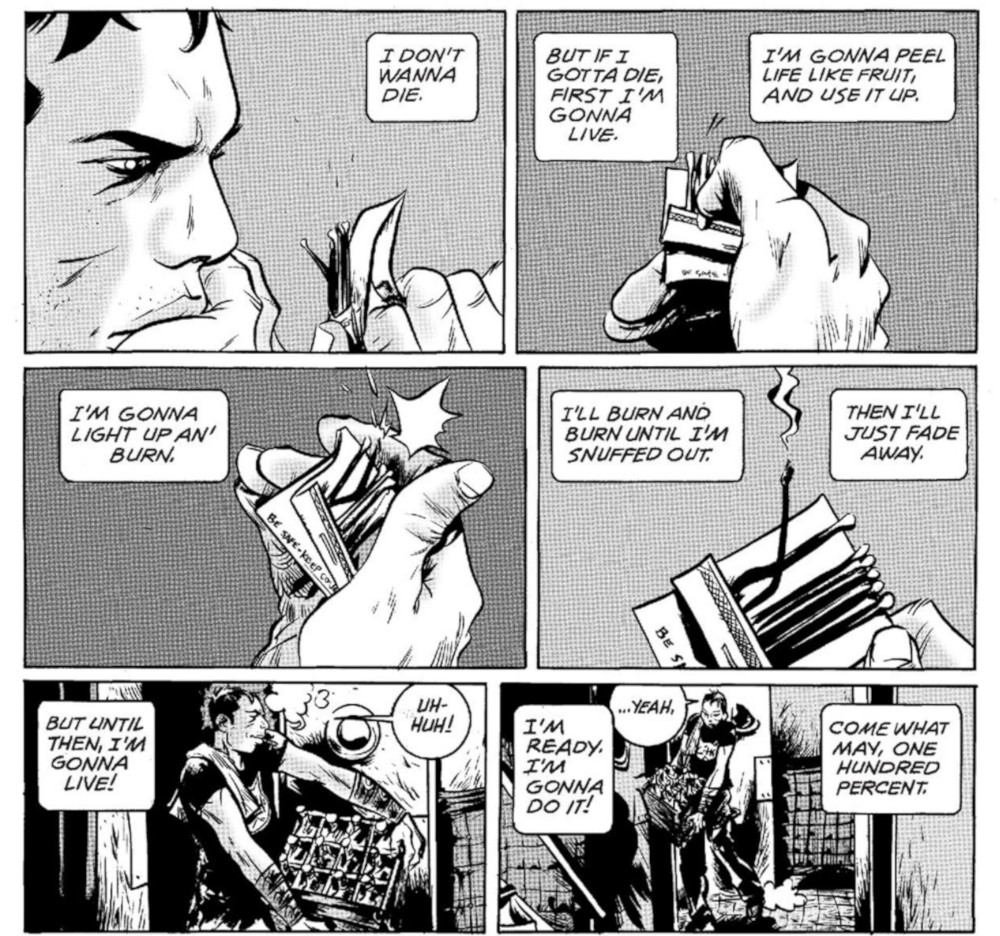

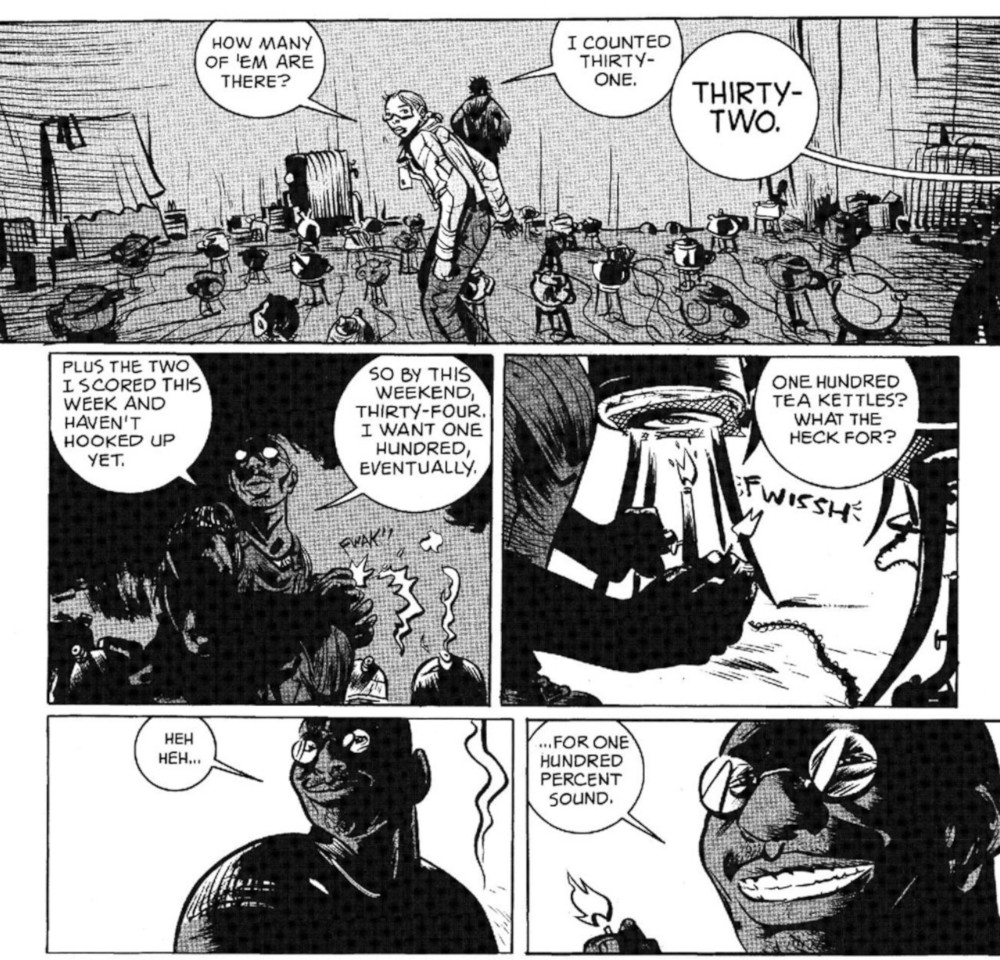

I’ve spent the past decade analyzing comics for my career, so sitting down with 100% in 2020 brings much greater appreciation of the craft on display from Pope, colorist Lee Loughridge, and letterer John Workman. I never really thought of 100% as a collaborative effort because it’s so steeped in Pope’s point of view, but Loughridge and Workman are essential in creating the book’s visual texture and reinforcing the atmosphere Pope evokes in his linework. Pope and Loughridge’s black-and-white artwork makes the story feel like an artifact from the future, and the delicacy of the shading complements Pope’s forceful inking. Workman’s sound effects are informed by Pope’s linework, and the two blend seamlessly to enhance the ambience of different spaces. Those sound effects also add to the brutality of the violence during Haitous’ Gastro fights, with the noise filling out the space around each hit.

I found an enlightening 2002 CBR interview with Paul Pope focusing on 100%, and he has a lot of really interesting things to say about the story’s connection to the superhero genre and its strong cinematic influence, going so far as to call it a “graphic movie.” I balk at the term because it feels like a way for Pope to gain respectability by comparing his comic to another artform, but he’s fighting against what readers expect from mainstream comics. The things that Pope says make 100% a “graphic movie”—focused on relationships and set in a specific place over a short period of time—are related to structure and plot, but not specific to either medium.

100% comes after the indie cinema explosion of the ’90s, and Pope taps into that spirit with a black-and-white character-driven ensemble drama that breaks from the mold of what readers expected from Vertigo Comics, a mature readers imprint that gave creators the freedom to take genre elements to their extremes. Pope followed that impulse in Heavy Liquid, and actively fought against it for 100%, instead using this strange future world to chronicle experiences that reflected the struggles of real people. The comic-book medium allows him to add extra spectacle to a dance routine, art project, or boxing match, but what drives the story forward is the depth of the relationships and learning more about these characters.

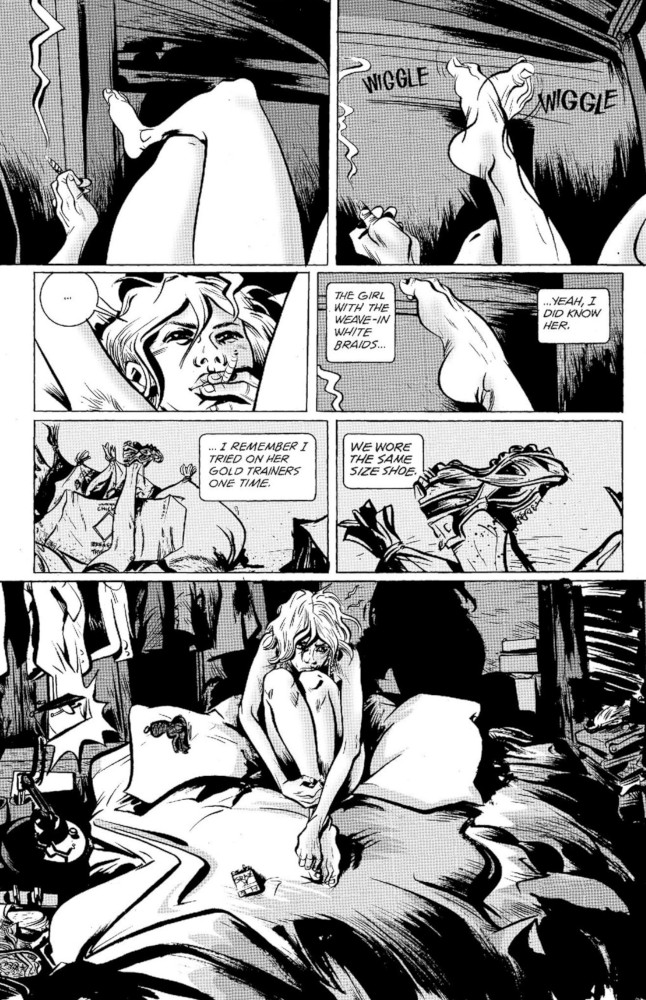

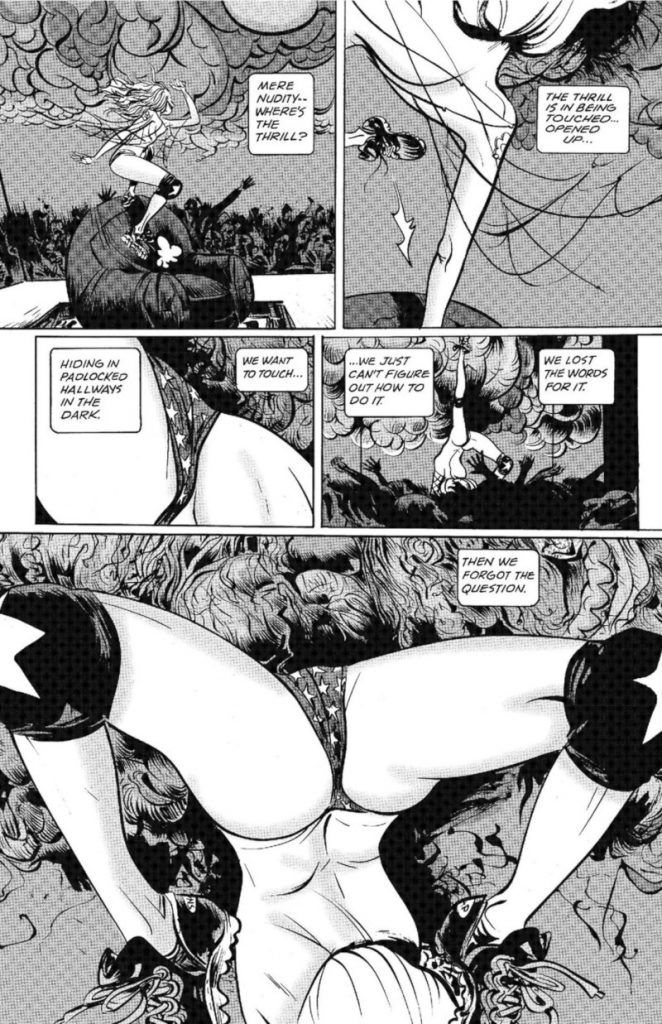

Legs, recurring in Paul Pope’s 100%

Legs, recurring in Paul Pope’s 100%

The story begins with a full-page shot of a dead woman’s upturned leg, her pale flesh propped up on a discarded cardboard box that used to contain 100% white meat chicken. In the CBR interview, Pope mentions that the recurring image of an upturned woman’s leg is tied to perceptions of women in this future world, and the leg is a symbol of both violence and arousal. Sitting in bed after buying an illegal gun for the first time, Kim lifts her bare foot in the air and wiggles it around, thinking about the time she tried on the dead woman’s gold sneakers, the same ones she wore when she was murdered. In the transition from two close-ups of feet, Pope captures the fear that comes with city living, the fear that creeps into your mind when you hear about people getting shot on the street and mugged on the subway. The fear that it could happen to you.

The next time we see a woman’s upturned leg is when Daisy is dancing in the Gastro cube, putting on a dance show as a crowd howls at projections of her insides. It’s the most dynamic moment in the story, using the visual language of dance to depict Daisy’s strength and grace on stage. Daisy is an artist in her own right, but her dancing body is just a vessel for the main attraction: the Gastro light show that ends with Daisy bursting into virtual flames like an erotic phoenix. At the start of the dance, there’s a shot of Daisy doing a backbend, both of her feet dangling in the air while she presents her star-spangled panties to the world. Like the opening shot of the dead woman, this panel doesn’t show Daisy’s face, stripping away her identity to make her a blank object of desire.

At the end of 100%, the heartbroken John decides that he’s going to follow Daisy’s example and run away, leaving his fate to a dart thrown at a map of the world. Wherever it lands will be his next destination. It’s not a good plan, but it’s something. I still haven’t nailed down how I feel about the ending; is it meant to inspire by saying John is exactly where he’s supposed to be, or is it a tragic moment trapping John in his current unhappy situation? Being stuck in quarantine only makes that reaction more complicated. My dart is stuck on my home address, and I feel far from 100% when I’m cut off from the people, places, and activities that shaped my old day-to-day life. And yet, Pope’s love letter to city life makes me all the more appreciative of the world outside my window. You don’t realize how magical it all is until it’s gone, and I yearn for the day I can experience the urban pleasures I used to take for granted.