How the Tamakis’ Skim helped set the stage for a YA comics boom

I didn’t have queer comics growing up. There were comics by queer creators with queer content, but they weren’t easily available and they didn’t address the issues I faced as a closeted gay teenager at the turn of the new millennium. 20 years later, the comics industry has undergone a drastic transformation. YA and middle-grade graphic novels have blown up in popularity, and they enthusiastically explore the experiences of young queer characters. I wrote about this trend last year in my Big Issues column on First Second’s Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me, an astounding adolescent drama that moves beyond coming out to look at queer love on a deeper level, and the lingering power of Laura Dean left me hungry to revisit a landmark work by its writer, Mariko Tamaki: 2008’s Skim.

Featuring art by Mariko’s cousin, Jillian Tamaki, Skim details a few revelatory months in the life of Kimberly Keiko Cameron, nicknamed Skim because she’s overweight. The year is 1993 and Skim is really into wicca and her art teacher, Ms. Archer, a bohemian goddess with freckles and curly red hair who teaches Shakespeare in flowing floral skirts and hoop earrings. Skim’s quiet, sullen demeanor puts her on the radar of the popular girls who have made student body mental health their mission after the suicide of one their friends’ maybe-closeted boyfriend, and while Skim isn’t suicidal, she’s dealing with acute depression stemming from her obsession for a woman she cannot have.

Skim is the first of two collaborations between Mariko and Jillian, introducing readers to the emotional richness that comes from the combination of Mariko’s introspective and complex scripting with Jillian’s intricately detailed, heartbreakingly expressive artwork. There’s a lot of tenderness in the storytelling, but the book doesn’t shy away from Skim’s faults, painting a thoughtful portrait of a young woman navigating a difficult time without a strong support system. I wasn’t like Skim in high school, I had a pretty big group of friends and was in a lot of extracurricular activities that kept me from wallowing in the misery of the closet. But I recognize her pain all too well, a pain familiar to any queer kid growing up in an environment that won’t let them be their true self. You develop a secret life hidden from the people who used to be your closest confidants, and the alienation only becomes deeper the longer you conceal the truth.

Skim’s cover image evokes the delicacy of Japanese ukiyo-e artwork with its tight close-up of Skim pensively looking up as she shields her eyes from the sun with her hand, and the graceful lines and lush compositions of ukiyo-e permeate the book’s aesthetic. Jillian Tamaki’s character work is overflowing with feeling, but I will always primarily associate her with immersive natural imagery. She became the first comic-book artist to receive the prestigious Caldecott Medal for her artwork in 2014’s This One Summer, her second collaboration with Mariko set in a small lakefront town in the middle of dense woods. The delicate coming-of-age tale illuminates a young girl’s adolescent metamorphosis by presenting it alongside her mother’s recovery after a miscarriage, and Jillian connects the characters’ emotional states to the environment to imbue the landscape drawings with even more power.

That same connection can be found in Skim, which takes place in a suburban town but still spends considerable time in nature. The story gives a visual prominence to the changing of the seasons, opening with a page showing fallen leaves blowing in the autumn wind. This is a transitional period, one where trees shed their leaves and reveal the branches underneath the foliage. There’s vulnerability in that bareness, and Skim becomes more emotionally raw as the fall gives way to winter. Skim’s relationship with Ms. Archer develops in the woods behind the school, where they smoke cigarettes and argue about the merits of Romeo & Juliet. During these initial conversations, the woods are bustling with activity, from leaves falling on puddles of water to squirrels climbing up tree trunks, gathering food for the coming cold.

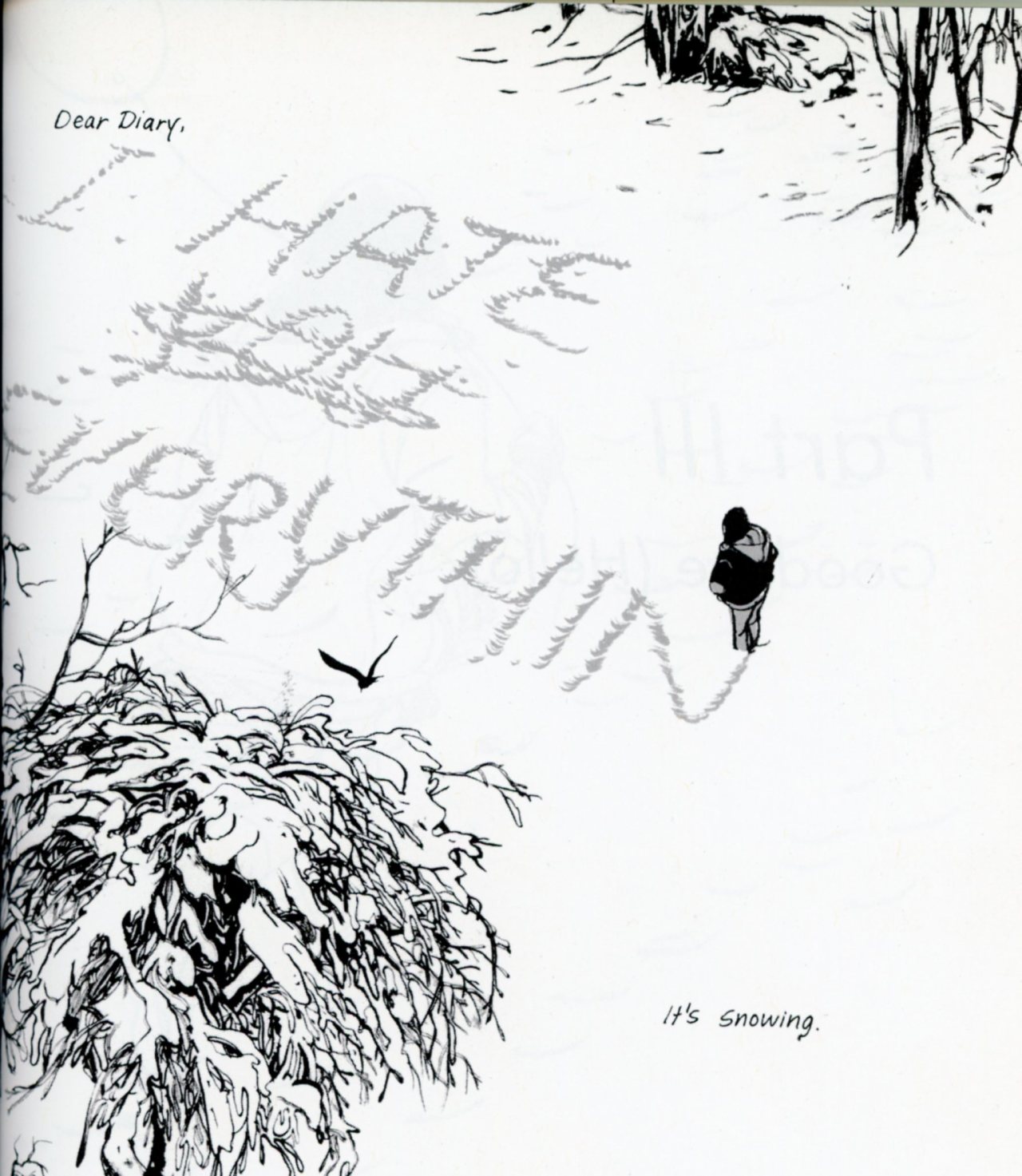

When Skim and Ms. Archer kiss during one of their smoke breaks, the life-changing moment is presented in a two-page spread that reinforces the couple’s closeness by minimizing them within the forest setting. This is a single image, but there’s a sequence of events happening here. On the left side of the image sit Skim and Ms. Archer kissing under a tree, but as the eye moves to the right, it finds the high school that turns this relationship into something rightfully forbidden. The wind picks up on that right half of the page, too, signifying the emotional whirlwind to come as Ms. Archer pulls away from her lovestruck student. Winter comes with brutal force as it coincides with Ms. Archer’s departure from Skim’s life, and this rush of isolation and resentment arrives in a zoomed-out, overhead shot of Skim writing “I HATE YOU EVERYTHIN” in a field covered in pristine white snow.

These images have stuck with me in the decade since I first discovered Skim at a branch of the Chicago Public Library, two years after coming out at 21. As I was exploring more of the city after graduating from university, I would stop into libraries in different neighborhoods and see what kind of graphic novel selection they had. It’s still something I like to do, even though I rarely check out library comics because my job as a critic means I have too many to read at home already. My big entry into comics was the first X-Men movie in 2000, and for that first decade, libraries were largely responsible for my comics education. The library by my house had a solid assortment of graphic novels, but my horizons were expanded significantly when I visited the library in the town where my comic shop was located. The comic shop would advise the library on which titles they should order, giving it a huge assortment of graphic novels from all corners of the industry.

Libraries were how I received my education, but used book stores were how I first built my own personal library. I can still remember the day I walked into my local used book store, Frugal Muse, and saw that someone had recently sold them almost an entire run of Preacher collections, which I immediately snagged. My personal copy of Skim comes from a used book store, Wicker Park’s Myriad Books, where I bought it for half of its cover price ($6.50 is still written in pencil on the top corner of the first page). I mention all this because I don’t remember most comics with this kind of specific detail. There’s something profound about Skim and when it hit me in my life, but outside of the personal impact, I’m also fascinated by how these distribution avenues helped set the stage for the YA comics boom that would come just a few years after Skim’s release.

I go to the comic shop nearly every week, but I never saw Skim at any stores I visited. Comic shop owners focus primarily on what’s popular in the comic-book industry and lean into those trends while librarians are tapped into the larger books market, giving them different criteria for the graphic novels they acquire. Skim’s publisher, Groundwood Books, doesn’t have a strong foothold in the comics industry so it was easy for Skim to fly under comic shops’ radars. But a librarian regularly checking out Groundwood Books’ catalog for children’s books is more likely to take notice of a new graphic novel, especially when the subject matter will connect with the huge audience of young female readers looking to see themselves reflected in the books they consume.

One of the great joys of being a comic-book critic in the 2010s was seeing how the graphic novel sections in libraries and bookstores rapidly expanded, indicating a sea change for the medium as major publishers committed to their own graphic novel imprints. This growth has coincided with the demand for more inclusive representation both on and off the page, meaning that we’re getting more graphic novels from people outside of the cishet white male perspective that dominated the genre for the last century. I didn’t have queer comics growing up, but younger readers right now have no shortage of stories to help them process their complicated emotions and find clarity in their own lives.

Enjoy this article? Consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more articles from Oliver and beyond.