“There’s a Feeling of Purpose”: Artist Ian Bertram on His Art and new Art Book Acheron

To see Ian Bertram’s art is to be wowed by it. If you’ve seen it, you know what I’m talking about. His work in comics — particularly his collaborations with writer Darcy Van Poelgeest at Image in Little Bird and its follow-up Precious Metal — astonishes with the density of its detail and the clarity of its artist’s vision. The School of Visual Arts trained artist is a staggering talent, someone whose work is anticipated by readers and his peers alike. And for good reason.

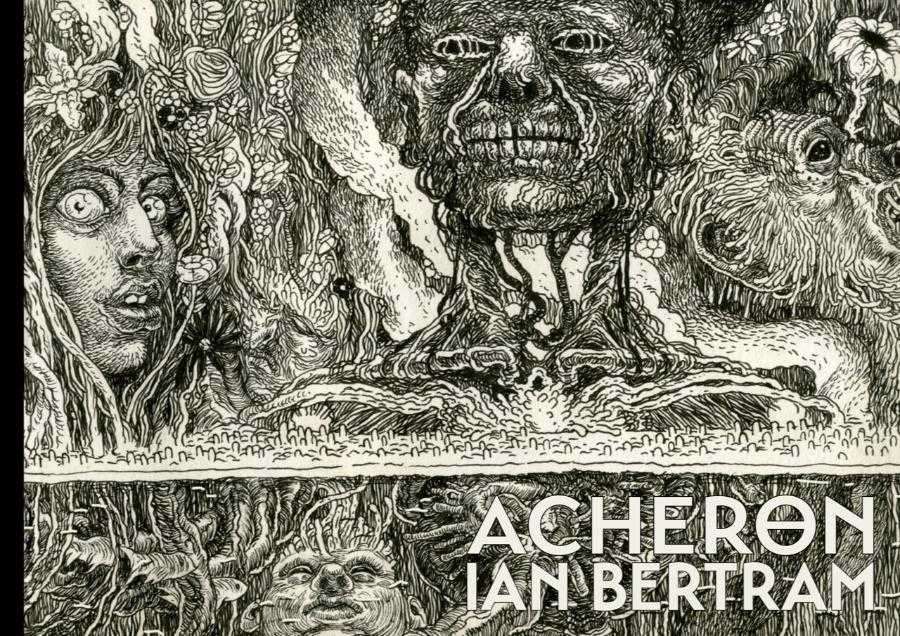

But if you’ve loved Bertram’s comic art, you’ve barely scratched the surface of what he’s capable of. For years, the artist has kept a private sketchbook where he channels his thoughts and feelings into his art. That alongside his gallery work showcases a different side of an artist mostly known around these parts for his comic work, and an artist who has an additional gear most were unaware of. Until now, that is. Bertram is currently Kickstarting Acheron, a landscape-oriented collection of that very same sketchbook that takes readers inside his heart and mind. It looks to be a heck of a thing — especially because Bertram is collaborating with the Tiny Onion team on bringing it to life — and a brilliant showcase of a brilliant artist, one filled with haunting and astounding imagery that goes beyond what we’ve seen from him before.

With this campaign having just under two days left as of this posting, I thought it’d be good to chat with Bertram about Acheron, his art, and what this sketchbook gives to him — as well as what he hopes readers might get out of it. So, that’s what we did, as Bertram and I recently hopped on Zoom to talk about the revealing nature of the project, the origins of this sketchbook, how the different sides of his art brain differ, the personal nature of this book, and a whole lot more. It’s a great chat, and one that’s been edited for length and clarity.

Additionally, it’s open to non-subscribers. If you enjoy what you read, maybe consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more like it, and to support the work that I do at the same time.

You are in the midst of your Kickstarter. How are you feeling?

Ian Bertram: It’s been pretty wild, frankly. I was a little nervous when we first launched just because I haven’t done a Kickstarter before and I was just like, well, what if it sucks? Just sort of the general feeling of be like, “Oh, I’m about to put something out there that’s very personal. I really hope that people respond to it.” And obviously people did and very quickly too, which was awesome. Within the first day I realized that people were interested in it because we’d met the goal. Now we just got to try to start to do the things that we were extra excited about, which is printing it on watercolor paper that mirrors the watercolor sketchbook that I use. So, it just has this extra thick quality, just little touches, like adding more pages and stuff like that.

I’m sure you’ve seen these art books from comic artists where it’s previously published material that people already have some level of affinity for, where it’s like Russell Dauterman drawing the Marvel Art of Russell Dauterman, which are cool things. They’re personal in the sense that they’re done by those people, but they’re not personal work that is free of intellectual property. Was part of your nervousness about it because this is you revealing a side of yourself that people haven’t really seen before, rather than work you’ve done on a notable property?

Bertram: I wasn’t concerned about the concept of showing vulnerable artwork to people. I think that that’s cool, and that’s the type of work that really excites me. But a lot of the things that excite me don’t excite other people. I had no real barometer for my personal work in a larger sense. I’ve shown personal work in galleries, and that stuff is fun, but it just depends on if one person wants to buy it. That’s sort of how you could measure success. It’s not the only way to measure it, but it’s one of the ways that you could.

And I think because this work is…it’s a harder touchstone. With things like superhero books or even Precious Metal or Little Bird, that’s playing with things that have been successful. With any type of superhero book, you can invent and change things within that, but it also has a built-in audience. There’s a history to it. It has weight to it. My nervousness was that this is just something that I’ve done in secret, just sketchbooks that I’ve been working on for years and years and years. I’ve shown it on my Instagram before and mentioned them to people, and I’ve certainly shown it to a few people at the conventions, but I just didn’t know if it would appeal in a way that would allow it to get funded.

I wanted to talk about the timeframe of the sketchbook itself. According to the Kickstarter, you’ve been working on this for 13 years. When did you start on it? Did you start on this sketchbook when you were at the School of Visual Arts and studying under people like Klaus Janson?

Bertram: I did start this sketchbook that we’ll be compiling when I was at SVA, back in 2011 or 2012. James Jean went to SVA and kept sketchbooks while he was there, and he was inspired to do that by a professor that was there. I took that same professor, and he also inspired me to keep a sketchbook. But seeing Jean’s sketchbooks, especially while going to SVA, it was cool to see someone approach publishing work in a way that was so personal. I just kind of fell in love with the idea of doing work in there.

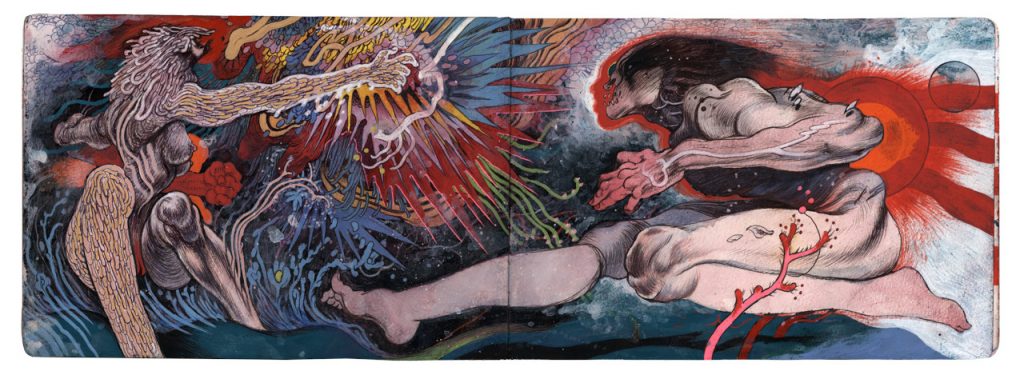

Looking at the art in Acheron, you can see your regular comic self in there, but it’s also not the type of art you would normally see in a comic. I know that you said in the writeup for the Kickstarter itself that it’s like much more personal work, as you said, “This is my sketchbook. This is the thing I’ve been working on for over 13 years. Intense, dark, working through some of the most difficult moments of my life. This is me finding something within the chaos that you can hold.” How do you view this art? Do you view this side of your art brain differently than you view your interior comic art brain?

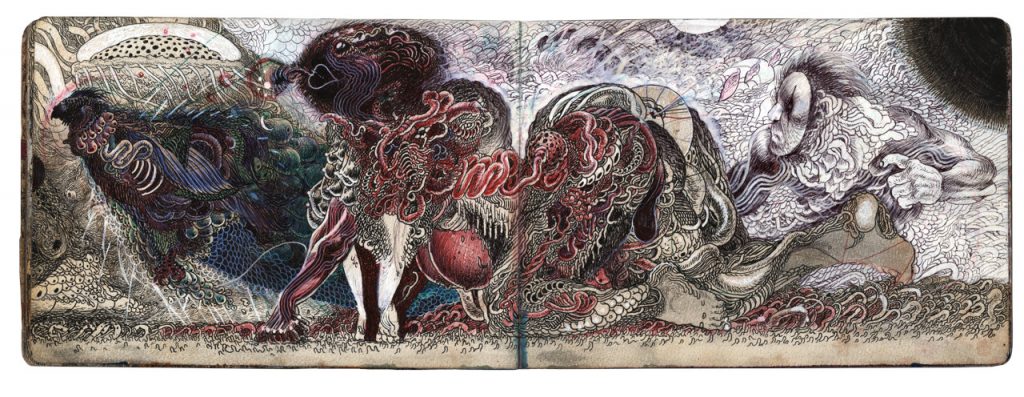

Bertram: Yeah, I do. I think that the more that I work in comics, the more I try to incorporate the aspects that are in my sketchbook. With the sketchbook, there are certain things in there that really no story is ever going to call for unless I write that story myself and want to work in those themes, which someday I might. But I think that the sketchbook is much more of a…I have a narrative to it, but it’s just the narrative of my life and lives are weird and strange and they don’t have a plot line that you are aware of as it’s happening.

You look back and you’re like, “Oh, I guess that’s what that was.” So, it just allowed me to, for lack of a better word, be a vessel for whatever my mind was going through and just have my hand transcribe that in the medium that I understand how to use. And so comic stuff is, there’s certainly…depending on the writers that you work with, I work with Darcy Van Poelgeest who is amazing, and there’s certainly a lot of similarities and thematically there in terms of content that I can include in the artwork. But with comics, everything’s in service of the story. And with the sketchbook, everything is in service of the release and the North Star is different.

Can you see your experiences when you look at the pages?

Bertram: Yeah, absolutely. It’s very strange. I think that there’s going to be themes when people look through the sketchbook. I hand-wrote an intro to the sketchbook. I wrote it like I draw in the sketchbook, where I wrote in pencil and then I essentially inked those pencils. And then I went back in with whiteout and edited things like that, just trying to find the purest, most honest version of what I wanted to say about the book. I’m glad I did it that way.

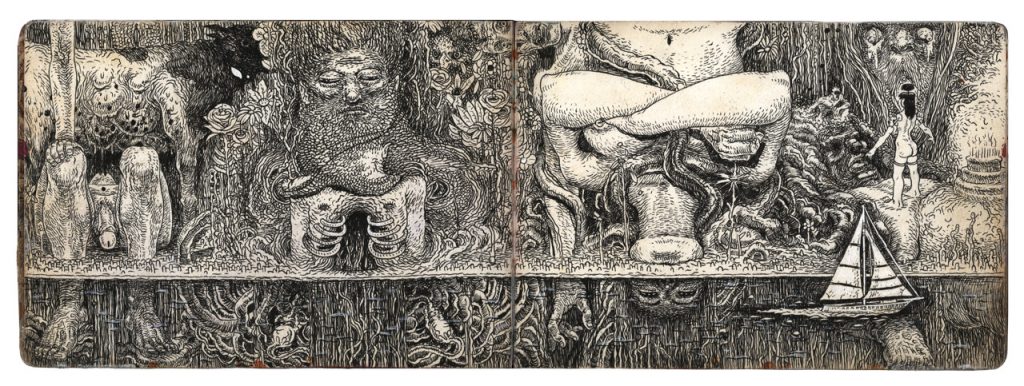

I realized a few things while working on it, but one of the things is the narrative involved in it. I see it and I see a lot of pain in it. And everyone deals with pain and everyone deals with difficulties to different extents. As I look back, especially through the earliest pages in the books where those are the furthest memories away from me so they’re the haziest, but seeing an image in there, for instance, there’s a sailboat in one of them…I know where I was when I drew that sailboat, and I know what I was thinking about when I drew that sailboat in a way that just thinking back on the past, it’s so hard to put yourself into the place that you were at. And so, it has a journalistic aspect to it. The narrative is just the points in my life where I felt compelled to work in this thing.

Do you have other sketchbooks?

Bertram: I have these two that we’re going to be putting together, and these are sort of what I think of as my sketchbooks. I have a sketchbook that I have worked in for comic stuff, just figuring out characters and scenes that I want to work through. But I approach that differently.

So, you reserve the Acheron one for specific things. As you said, it’s almost like a journal for you. Is that the case?

Bertram: I think that the best way to describe the process is I would feel overwhelmed in some way, and I know that when I feel overwhelmed in that specific way, it’s because I haven’t done something that has released things in the way that I feel like art should for me. And then I’ll do something in my sketchbook, or the other thing I’ll do is massive paintings for myself. I think that the sketchbook is something I can do if I’m traveling somewhere or if I want to not be in the studio. I do huge paintings and big drawings for myself as well as a release.

When I think of sketchbooks, I think of…I don’t want to say utility. It’s just people figuring out ideas or drawing their version of a character or something like that. But it seems to me that it’s almost less about wanting to drawing in it, it’s more about needing to draw in it. What does drawing offer you as a person?

Bertram: Oh, man, that is a very complicated, very deep question. I think that that’s probably the big question with art. Why make it? What is it? What does it bring to you? I think that there’s a feeling of purpose, but there is a release, so what it gives me is sort of an ability to maybe just transcribe whatever subconscious thing that I’m focused on at any given moment. It’s a tool in that way, but it feels limiting to call it a tool. It’s certainly more than the sum of its parts.

The room is much bigger on the inside than it is on the outside.

Based on your work that I’ve seen from Acheron, it seems like you’re trying to take as much advantage of the room you have available, at least in that sketchbook. Most of the time when I see these types of sketchbooks, though, they’re portrait oriented. I think it’s a lot of comic artists think in a comic shape, if that makes sense. But this is landscape. Why do you sketch in landscape?

Bertram: The book that I bought was a Moleskine Watercolor. I loved the format, and I loved the size. It just feels very satisfying to hold, and I think that the book itself is a landscape. There’s certainly an aspect of comics where it’s like we have a panel and then we work within that panel or a page, and then we create panels within that page. This very much felt to me sort of…like the edges of the entirety of the sketchbook are where the image ends.

Withthe Acheron stuff, one of the things, and I think it’ll be very apparent when the book is published is I’m working in this above and below type of imagery where there’s the Acheron, the river that’s at the bottom of the page, and then we have these sort of gods and goddesses wandering through this space, and then we see below the surface and we see them extended and what’s happening underneath. And one of the things about this long format is that I could just continue this forever, essentially. It’s just one image becomes the next, becomes the next, becomes the next, and we could absolutely just print…I don’t know how many of the pages in the sketchbook I did with this above and below type of style, but it’s at least 20 pages of the sketchbook. We could extend that into one giant print, and it would all just bleed together into this massive story. Which is very cool.

That is very cool.

Bertram: And that’s certainly something I’ve never seen in comics. Hopefully people can be…when they’re holding the book in their hands and flipping into the pages, that is certainly a way to view it as just one extended stream.

Was it your idea to Kickstart this? Or were you kind of pitched on the idea of bringing it to life in this sort of way?

Bertram: It’s funny, you mentioned Sanford Greene when we first started talking, 1 and man, that guy is amazing. But I have been wanting to publish this for a long time. The idea of doing a Kickstarter was so daunting that I was like, well, I don’t want to do a Kickstarter. I just want to make this work. And then I talked with Sanford and…just maybe the way he said it to me was so sort of like, “Well, why?” He was like, “Why haven’t you done this?” It was so matter of fact. He just cut to the chase. Maybe it was the time and place in my life too. I was just like, “Oh yeah, that’s spot on. Why am I not doing this?”

Did he think you were making excuses or something?

Bertram: I think that he heard me talking about the idea of maybe doing it sometime down the line, and he just brought the timeline up exponentially when he was like, “Well, why not do it right now? Why think about it as a future thing and why not just do it now?” Sometimes someone says something to you and it just hits you at the right time. And yeah, it was actually that time when you and I met and ran into each other at San Diego. It was in that little hallway on the second floor. That’s when he brought it up, and I was like, yeah. So, that was a catalyst.

And then James Tynion is a dear friend. We share a studio together. He started Tiny Onion, so I just reached out to him, and I was like, “Hey, is this something you could see yourself doing?” And he showed it to Courtney (Menard), who is their Director of Production and just a wizard. She’s hands-on in all aspects and phenomenal to work with.

But then we all just got really excited and they’re handling the part that I was worried about handling. I don’t want to handle the logistics of shipping these books to people. I’m an artist, right? That’s a nightmare. And they’re going to handle that, so everyone’s going to get their stuff on time, which is the classic problem with Kickstarters for artists. I just get to compile it and work through design stuff with (Menard). She has pretty much done all the design stuff herself, and it’s all been phenomenal.

You mentioned the things that got unlocked, like the black ribbon bookmark for every copy, the 200 GSM watercolor paper, the inside back pocket, and beyond. Were those things that you talked with Courtney and the rest of the Tiny Onion team when it was being developed?

Bertram: Yeah, I was very specific from the beginning that I wanted to do as close to a one-to-one reproduction of these sketchbook. So watercolor paper and the sort of Moleskine format. And she asked me, “Okay, can you send me a link to the exact sketchbook that you’re using?” And she saw the ribbon on it.

Yeah, I have a Moleskine right next to me. It has a ribbon too.

Bertram: Yeah, they do. Mine are so old, I feel like that must have ripped out at some point. But yeah, they come with a ribbon, and she thought that was a cool idea.

Have you seen any test versions of the book yet?

Bertram: No. Now with the Kickstarter getting the funding we need, I am sure we’ll start the process of getting the tests or whatever. But it’s a printer that they’ve evidently worked with before and that they trust. Obviously, we’re not going to just ship without testing it. We’re going to test it so we can be confident that it’ll look great.

I can’t wait to get my hands on it.

Did you call it Acheron before this Kickstarter came together? Or did you need to name it for this?

Bertram: I had been calling it Acheron for a long time. I had printed three pages from my sketchbook and put them in a show a while back, and at the time, I had to think of a title. This was 12 years ago or whatever. And it was after I had drawn this river, and I was like, “What’s a great name for a river?” I just started researching rivers and I guess I found the name. I loved how it sounded, and I looked into the history of it. It was so fitting in a Jungian way where there’s this kind of collective unconscious aspect where I am doing this work before I know about the name for this river of woe. These concepts, these feelings, the drive has existed for a long time and people have described it in different ways and written about it and articulated it in different ways, and it just felt very fitting and tied it to a larger base in my mind.

While this is a private sketchbook, it seems like you did let others see it. How do you feel about the idea of…right now I think you’re at 626 backers? 2 Let’s say you end up with a thousand backers. That means a thousand people are going to get a book that is full of art that represents you in your life in a way that, I don’t want to say Little Bird or Precious Metal do not, but it represents very specific parts of you. How do you feel about that?

Bertram: I would like to be the person who puts that type of work out into the world. That is the work that is the most impactful to me and the work that inspires me the most. And I feel like the work that comes closest to art, however you want to describe that, and I feel it’s stuff where people are like, “Oh, maybe I’m giving too much of myself.” I feel like if that’s a concern, that’s usually something that is worth following even more. So,yeah, I’m excited.

One of the things you’ve mentioned is the description of the work as private. I think it’s a bit of an editorial term because I’ve shown this book to the people who are closest to me in my life over the years. And I can count on one hand the amount of comic cons that I’ve done over the past decade, but I brought this book and have shown it to fellow artists, so it’s something that I have shown to a very small number of people ultimately. And I think that that kind of slow process allowed it to become a little easier to show it to strangers, because showing it to people that are very close to me is easy. They know me. They know the struggles I have. They know what I’m interested in. They know my joys, my sadness, all the ups and downs, and so they can kind of have maybe a deeper appreciation for it.

I’m excited, and I’m very curious how people react too. When I go to conventions and people come up and talk to me about the book, I really would love to hear people’s interpretations of the work or what parts stuck out to them, or if any of it felt like thematically close to them. If it felt like there was a kinship there. That’s my favorite stuff. The impactful stuff that reflects the artist, the person who’s doing it. Sort of like an auteur type of thing. My favorite TV shows, films…it’s a person’s vision. That’s also true of my favorite comics too, where it’s usually an individual or a team that works incredibly closely together. An individual’s work is just sort of immersing myself in their mind.

That is really inspiring, and it feels like it has a purity to it somehow.

Thanks for reading this conversation with artist Ian Bertram. If you enjoyed what you read, maybe consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more like it, and to support the work that I do at the same time.