SKTCHDxTINYONION: Part Five, Thinking Globally

It’s been a lengthy stretch of travel for writer James Tynion IV, with trips to varying conventions across Europe and beyond over the past calendar year. And as you may know, I myself just returned from a vacation in France. As two people who can’t turn off our comic brains, both James and myself walked away from those experiences inspired. Seeing how comics are thriving in other countries, whether that’s the manga boom coming from Japan or the torrid love affair France has for the art form, was exciting, especially considering how different it is from the market we’re used to seeing. Because of that, it made us both wonder: What could the American comic industry learn from the wider comics market across the globe?

Unsurprisingly, that’s our focus in the latest SKTCHD x Tiny Onion interview.

This conversation finds me quizzing Tynion on his thoughts about not just what he saw from comic publishers, conventions, and the overall industry in France and other countries, but his views on the global comics market and how much it’s thriving — in different ways than the American one is, quite often. We dig deep into that subject, exploring what could be learned from manga, bandes dessinées, the markets and publishers that sell them, and a whole lot more. It’s an exploration of how other markets are succeeding, and what from that success could lead to real gains for people within America, both for today and tomorrow.

It’s an interesting chat, and one that’s open to non-subscribers. It’s also been edited for length and clarity.

We’re taking a bit of a turn in this month’s conversation because it isn’t oriented on the direct market or the larger American comic industry or really even specifically your work, although we will talk about those things. Instead, it’s going to be built on some recent trips we’ve both taken to Europe and some larger international trends in comics, particularly the endless rise of manga in those countries too, which is just insane.

We will start with your take on all of that. This is broad, but what were your big take takeaways from your trips to Europe from a comic standpoint? Did you come out of those feeling like you might, or the American comic industry might, benefit from rethinking things a little bit?

James: Oh, absolutely. Every day I was having that reaction, just walking through the different comic shops and bookstores and manga-specific bookstores in these countries.

Back in the fall, I did the insane thing of having three trips in a row back to back. I did Lucca, the comics festival in Italy, followed by a convention in Madrid, and then I did Thought Bubble in the UK. And that was an amazing trip and I absorbed a lot of information there. And then I came back home for a month and a half. Actually, I did a trip to Singapore right in the middle of there, but right after that I did a trip to Angoulême in France and did a book tour around France. So that’ the grounding for a lot of what I’m talking about today.

And really the biggest takeaway is the power and diversity of the medium as it exists over there. There was no single thing that became more apparent to me than the fact that the American direct market siloed everything into superheroes for decades, while the rest of the world has the superhero section up and running — even in Japan, the superhero section’s up and running — but it is not all that the industry offers. And because of that, it has been allowed to thrive and reach a much wider audience.

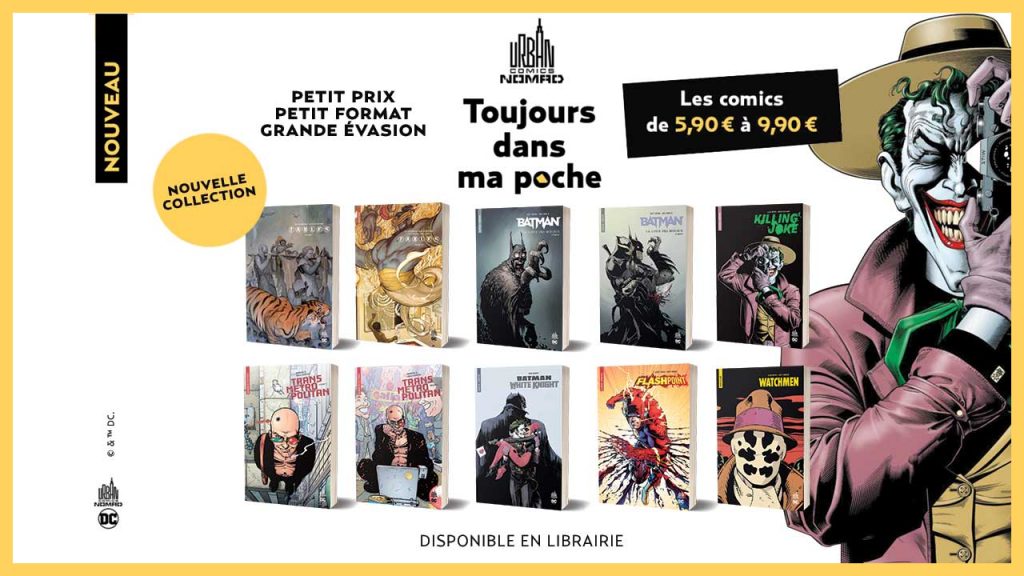

Honestly, I found it incredibly gratifying to see that. For people who don’t understand, the American comic book market — both the book market and direct market together — is the second-largest comic book market in the world. The largest is the Japanese market. The second-largest is America. Those are the comics that you can pick up at your local comic shop or your local bookstore. And then the third-largest market is the Franco-Belgian market, which is France, Belgium, and Ontario. And it is a very, very large market that I have lots of thoughts about, and I’m sure you do too. But yeah, getting to see it all in action, it was just like, “Oh, this is a healthier version of what comics can be, both in a culture and as a media.”

This is not an anti-superhero take or something like that. I love superheroes, you know that. You love superheroes, I know that.

James: Yeah.

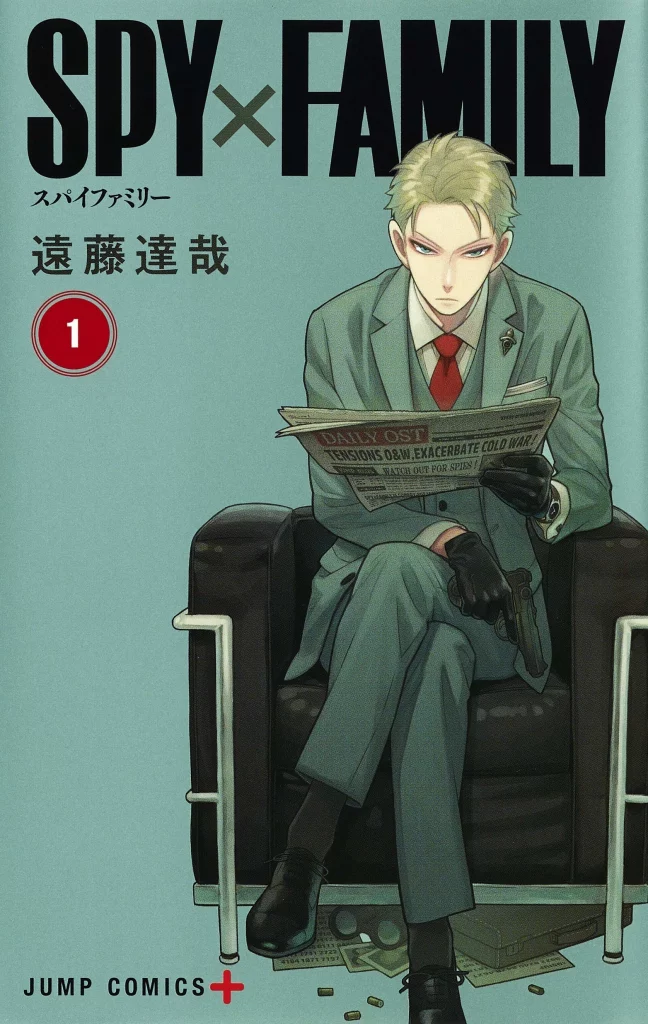

But you can look at the French market as almost like an alt universe version of what we could have been if the American market had not been so solely focused on superheroes. You even have publishers like Urban Comics who are doing the same thing as we are over here, where they’re publishing DC Comics and they’re publishing Boom! and they’re publishing Image, including your entire library. And they’re doing it in a completely different way that fits that market. The interesting thing is that part, the part that is absolutely dominant in America, is a very small portion of the overall market there.

From what I understand, manga is about 40% of the market. It’s even bigger there than it is in America. Then BD, Bandes Dessinées, is way bigger than the English translations are in France. That’s not everything. People like Emil Ferris, her book, My Favorite Thing is Monsters, that book is a sales giant in France and it’s because they respond completely differently to comics there. That’s one of the interesting things…this alt universe that I’m talking about is, to some degree, able to exist because it’s just a much more mature and thoughtful comics market that looks at the medium much differently than we do, both culturally and commercially.

I think that’s one of the difficulties of replicating a lot of what they do. But do you think there are things that we could take away from that overall? Are there things you think that we could be applying from their approach to what we’re doing here and use those to create a more sustainable or at least more successful future?

James: Absolutely, and I would point to manga as the reason I believe that, because when we talk about the French market, of course we’re talking about these art book tomes that are beautiful, hardcover beasts.

Everything’s a hardcover.

James: Yeah, everything’s a hardcover.

One or two volumes come out a year. It’s a slow progression, everything takes its time. Even the long-running series are like that, but they have more commercial titles that are more salacious. But manga is the most mass market product that exists in the comics media. It is wildly appealing, there’s sex and violence up the wazoo. It is not just a story of sophistication, it just isn’t. The things that appeal to readers appeal to readers in every country. I believe that thoroughly. I think that a lot of the sins of the American market are things that we all know, like it is insular, we kind of went down one narrow path for a long time, closing ourselves off to broadening our perspectives.

In France, the violent Western comics, which are very popular there, are side by side with the most art house things. Here in the U.S., it’s like the Fantagraphics/Drawn and Quarterly part of the industry is a completely different animal to direct market comics, which is a completely different animal to the book market YA comics, which is a completely different animal to comic strips and webcomics, which have never really been folded into the same ecosystem. We kept all of our lanes separate.

We forget even in America, outside of superheroes, some of our most enduring characters in pop culture are characters like Snoopy, Popeye, and Calvin and Hobbes, and all of them came out of the comic art form. It was delivered in a different way, but just pretending that we are not capable of delivering a mass market product is just defeatist. And I don’t believe it because if it were true, manga wouldn’t be able to come in and wipe the floor with all of us.

You’ve tapped into something absolutely essential to all of this. If there was one core takeaway from my experience, it’s that those separate lanes don’t exist in France. They’re all in one place. And I think sometimes, and this isn’t and insult on anybody who thinks this, people talk about how comics should be on the newsstand. “They should be like they used to be.” I don’t think that’s necessarily right because even in France it isn’t that they’re specifically relegated to a place. They’re just everywhere. The accessibility is through the roof. You can go into a Relay store, which is a train station/airport-oriented convenience store that has the sort of things you’d find at a Hudson News in America.

It’s like Hudson News, except for there’s an entire section of comics. You can go in there and buy Tom King and Mitch Gerads’ The Riddler story from Batman: One Bad Day. You can buy a bunch of Marvel trades from Panini. You can buy Manga, you can buy Bandes Dessinées. These are all options and they are all together in a wide variety of stores. I hate to use this term, but you’re not ghettoing different things into different positions that are all separate. Everything’s together and it’s all accessible. And I think that’s the core. Comics are so much more accessible. Because of that, I think it’s easier for people to fall in love with them.

James: Yes, I think that’s 100% true. Accessibility is key. I do feel like there have been obvious attempts to push towards accessibility here. A lot of the ways in which bookstores work, and especially big box stores, there have been all of the Walmart experiments, but the way that Walmart works is it’s if people don’t buy those books, then everyone ends up in the red when they try to go down those roads. It’s hard. I’m not trying to say it’s not hard. That’s especially true when we’re trying to pivot and we’re trying to pivot while another product from another country is coming in that is cheaper, has more pages, and is just easier to understand. It’s like you pick up volume one and you keep reading to the end, even when there’s ten versions of it.

These are all things that so many people have pointed to before. It doesn’t feel like any of it is hugely novel to say, but when you get to visit the other universes of comics that exist outside the U.S….honestly, you know what it makes me want more than anything? It makes me want to play in a part of a global market a lot more than we do. My stuff is available in France, like we said, through Urban Comics. I’m very grateful we’ve been having some real success over there, especially with Nice House (on the Lake, Tynion’s Black Label series with Álvaro Martinez Bueno). Nice House in France is outpacing Nice House in the U.S., and it’s doing very well in the U.S., which is extremely exciting. And I’m very grateful. It’s a lot of things that you’d expect, like Something Is Killing the Children, especially with Werther Dell’Edera, is doing very well in Italy. I’m very happy about that.

Something Is Killing the Children’s doing well everywhere, but one thing that drives me nuts is how hard it is to penetrate the Japanese market as an American comic. The superhero books make it over there, some of them do, not everything, but while there is a bit of a wall up between the American and Japanese markets, it doesn’t allow for the kind of interplay that I think would make a healthier global market. And it’s down to the little stuff. Why don’t American comic book conventions invite more manga creators? Just in terms of the fact that it would be amazing to go out drinking with a manga creator.

I remember people lost their minds when TCAF (Toronto Comic Arts Festival) had Junji Ito as a guest. Every comic creator I knew that was going to be at TCAF was like, “I have to meet Junji Ito. This will be unbelievable.” That stuff rarely happens.

James: The fact of the matter is most people who work in comics are just big comic book nerds and it’s not about a kind of competition, us versus them, it’s about an interchange. It is about the ways that we influence each other. You look at something like My Hero Academia…it’s a love letter to American comics and superhero comics.

When I was in middle school, I had to basically decide at a certain age, “Okay, am I going to go down the Western comics path or the Eastern comics path?” at the bookstore, because I only had enough allowance to go down one of those two roads. And I chose American comics, but most of my peers went down the other road. Everyone my age who is making comics grew up influenced incredibly by manga and anime.

That’s through the roof today though. The next generations that come up are going to be even more so.

One of the core divides between the way the different markets approach these things is at a time when single issue comics and single issue publishers are like, “What if we made everything more expensive?” It’s interesting to see that when manga publishers are instead asking, “What if we made everything less expensive?” VIZ announced VIZ Manga this week. VIZ Manga is their new app that’s $1.99 a month to get access to 10,000-plus chapters. They already have Shonen Jump. Kodansha announced the K MANGA app. All of them are incredibly reasonably priced.

That strikes me as a meaningful difference, both in Japan’s approach and in France’s. The market in America is very much oriented on growth of revenue through getting more out of an individual, versus other publishers from other markets are more oriented on growing the number of readers. Do you think that’s something actionable or do you think it’s more about finding the right solution for the right product?

James: That’s a really good question. Obviously, the more you get for the least amount of money is always going to be the better offer, but a lot of the decisions that we’ve made in the American market have been to preserve the local comic shop. And those are important decisions because here’s the other thing that’s kind of obvious when you think about it. One difference between America, France, and Japan is the fact that it’s harder to run an independent bookstore in America right now. It just is. And running a small business is very difficult.

Especially in the major markets that need to be the most served, it can be cost prohibitive. I live in New York City and there are lots of comic shops here, but given the number of people and the fact that I’ll go to a small town in Pennsylvania and they’ll have four comic shops, New York should have more comic shops. You walk down the street in France and you’ll pass like five different stores and then every independent bookstore also has a BD section.

My wife kept thinking that I was intentionally taking us to comic shops because we kept coming across them. And I was like, “This is happening by accident. I could not possibly plan to go to this many comic shops,” because I’m used to going to a place and if I see a comic shop, I’ll pop in really quick. And in France it was constantly happening completely unintentionally.

James: This is the reason the book market keeps looking at comic shops. We’ve actually kept an entire ecosystem of independent bookstores alive during the few decades that most of them died. That’s valuable. That’s incredibly valuable. Our loyalty to our local comic shops are one of our great strengths.

But there’s still been a limited scope in what we’ve approached. And while there are lots of forward people thinking in that space, they’re geared towards the person who walks in knowing everything and is able to find what they’re looking for. While shops elsehwhere, they work like bookstores. You go in and you pick up a book and then you pick up the book that looks most interesting to you and you can flip through it and there’s pretty pictures. It’s a great system.

And so much of it is face out too, which is a huge difference. It really favors the art.

James: Yeah. And one of the big things that we’re going to have to come to grips with over the next couple of decades in the American market is the value proposition of the periodical. It’s very expensive for what it is. But it’s also what feels like a comic book. It’s hard for us to even imagine comics coming in a different format, but it doesn’t make any sense to anybody else because the average human doesn’t even really interact with magazines anymore. Comics are one of the only ones that exist in that kind of periodical format anymore, which is part of the reason they’re getting more expensive to make. There’s no longer printers that specialize in making magazines. We used to just be the extra thing that the magazine printers made on top of everything else they do.

As we become more and more of a specialty product, it’s hard to go mass with it in that way. But I love writing single issues. I write best in single issues. Frankly, the one book that I was trying to write just as an OGN was Wynd, and that ended up being turned into single issues.

You were going to do the same with The Closet too, right?

James: Yeah, The Closet too. But once I started writing Wynd, I wrote the whole first volume thinking it was going to be released as an OGN. And then we carved it up, added a few scenes to make it work as a five-issue mini because BOOM! wanted something to come out of the shutdown in 2020. That was immediately in store as a new number one. And I got extra pages out of it, which I’m always looking for. But then every further volume I’ve just written in issues because I knew that that’s how it was going to come out. I’ve never experimented in that format. I would love to. I have no idea how to. It terrifies me.

It is interesting though that the differences in formats are so broad. With manga, you have the Shonen Jump-type magazines that contain the individual chapters. And then they come out in tankōbons, but then there’s also those very reasonably priced apps that we now have in America, like VIZ Manga for $1.99 a month, and that leads into the tankōbons as well, with all that leading into larger collections of multiple volumes. Then in France you have these big, beautiful hardcovers that look great on a bookshelf.

Meanwhile, America just sort of aims for the middle ground that isn’t really either, where it’s not high end and it isn’t really accessible, it’s just disposable yet reasonably expensive. It’s very clear when you look at the market and the growth of the book market in America that there is a lot of interest in the comic book art form. You can also look at how Webtoon is used here. It’s very heavily used, but the difference is, I don’t want to boil it down to one thing, but it does seem like format is a major issue because younger readers are going crazy for manga, younger readers are going crazy for Dog Man, younger readers are going crazy for YA and for middle grade stuff, younger readers are going crazy for Webtoon, but they’re not necessarily going wild for a lot of the stuff that comes from the direct market.

Part of the problem is it’s nice to say that all these things we should learn from, but there are economic reasons that makes it difficult. And then on top of that, the direct market is very slow to change. And I don’t know how to reconcile those things, James. I think if I did, I’d be running comics.

James: This is the question. These are the big questions. I do think that one big thing that we just need to throw out the window is our dedication to a single format size.

Yes. I completely agree.

James: That is one of the biggest things that someone who just handles books in their day-to-day life, just regular books with words in them…the size of a comic is strange to them. It’s not like anything else they hold, because once again, this came from magazines. We were originally the larger magazine format and then we shrank to the smaller periodical format that we recognize as a modern size comic book. But we are a variation on a thing that doesn’t exist anymore, and that’s the reason that our trade paperbacks are the size and format they are. But everywhere else in the world, that isn’t what bookshelves are built for. So you can’t put a bunch of American comics in the middle of the crime section in your bookstore if everything is being shelved to suit a standard size.

It is an entirely strange format. And that doesn’t mean we should never use it because some things are perfect in that tall page. But the more art book style things that come out of the BD market, they’re so satisfying. They’re just so big. You get to see so much art. And then the flip side of that is the manga size is so satisfying. It’s like a pocket-size book. There are only a few panels a page. There’s a density of information. But It’s simpler too. There’s this balance that once again, we exist in this uncomfortable middle, where our stuff is very expensive to make, very expensive to print, very expensive to buy, and it’s in a format that they’re only are only a few thousand specialty shops in the country that are built to sell. And that is difficult. It’s difficult to build a cultural foot stone on that.

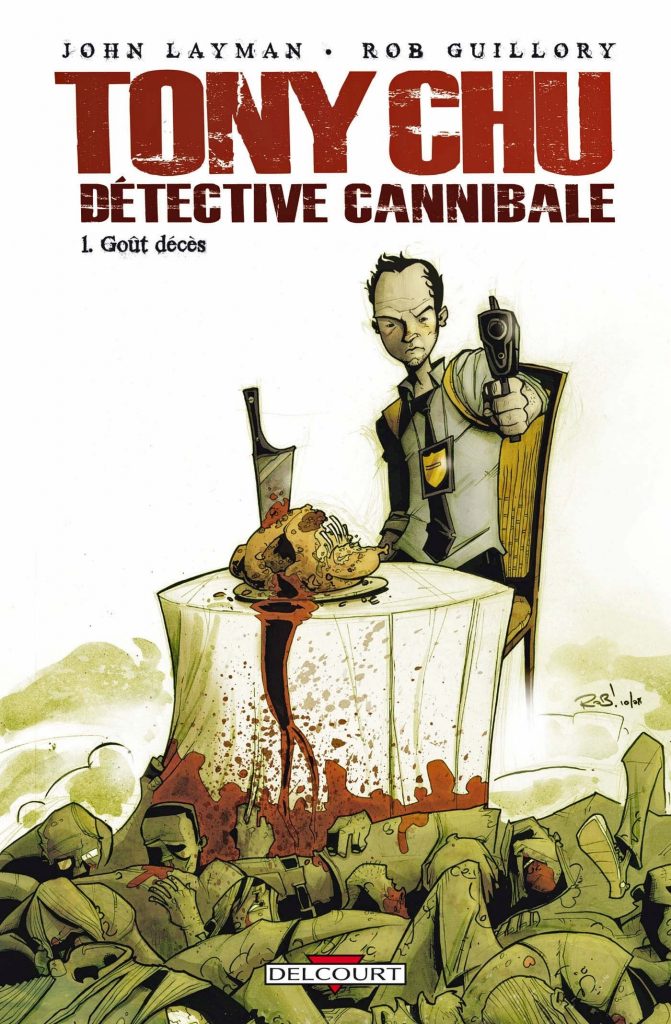

That’s why I think Urban Comics is super interesting. They are taking a product that sells in America and doing it a different way. They have the Nomad product for DC Books that come in digest sized versions of DC/Vertigo books like Y: The Last Man, Kingdom Come, etc. You can buy all of Crisis on Infinite Earths for $6.50, which is insane. And that same book would only be a hardcover in America and it would cost like 50 bucks. I don’t know that that’s actually true, but I’m guessing.

James: They also offer the hardcover version of Kingdom Come, so you can have both. You can have the big fancy version and you can also have this pocket-size version. I love those pocket-size versions. When I saw those, my brain exploded.

It’s interesting to see how differently they approach things. Different formats, production value, design, all that. Even just how they’re thinking releases out. And it’s interesting to get a funhouse-mirror view of how a different market would approach the same material and how effective it is. And yet – and this isn’t me disparaging DC because I’m sure that they have their reasons for not doing things like the Nomad format – but from a reader’s standpoint and talking to my wife, who’s not a comic reader, she’s like, “This is so much easier. If this was the way it was in America, I would read it.” And she’s completely genuine when she says that. They have the easy button on a lot of this and it’s really fascinating just to see how Urban Comics is rethinking the same product in a different way.

James: It’s endlessly fascinating. And the books are so beautifully designed. I think people have said for years, the French editions are always the most beautiful editions of comics that exist in the world at any given point. My oversized Nice House on the Lake hard covers that are done in the big BD format, it is such a gorgeous volume. Both of them are just unbelievably beautiful books.

I bought several books there just because I wanted to look at them in the big format. I can’t read French, but it’s very satisfying to look at them, James.

James: Oh yeah. It really is. And that appeals to us. We are a certain type of nerd that wants to pour over all of the images and all of that. But then some people are just looking for something that gives them a quick jolt of story. And then you have these digest-size things that are cheaper. It is about variety. Tere’s easy mode, hard mode, and difficult mode. But in the American market, we put the difficult mode release up front, and most local comic shops are in difficult mode.

The comic shops in France are just easy to understand. The idea that they actually organize things by genre shouldn’t be such an unusual thing. It was so easy to find things based off of that. I loved all the face out comics they have. But the encouraging thing about that is it reminded me of the best direct market shops. The best direct market shops are like that or moving in that direction. You go to Big Bang in Dublin, that’s what it’s like. You go to Books With Pictures in Portland, that’s what it’s like. You go to Floating World in Portland, that’s what it’s like.

I’m sure I could just list other shops in Portland. There’s a lot of good shops in Portland, but you know what I’m saying. We are moving that way, but it’s almost like a generational thing where there’s a lot of retailers that are still around that have been doing this for a long time, and that’s great. But they also represent a different way of doing things. And I think that it’s encouraging that some are moving in the other direction.

James: 100% percent. This taps into some of the larger conversations that we’ve had. It’s finding the balance between chasing the collector market, which focuses on the periodical and on varying covers and all of that versus how do you rebuild your shop into an independent bookstore that focuses on graphic novels. A place that has something for anyone who walks into the shop. And then in an independent bookstore, you need to be adept enough to point people towards different things. But this is where we run into cultural walls too. People don’t know that they can walk into a comic shop and get anything. They think that they walk into a comic shop and it’s just going to be Spider-Man and the X-Men.

And that’s not entirely wrong. But to succeed as a medium, we need to lean into these other places. I love looking at the global market and seeing that the books that are succeeding the most globally are the books that are in the vein of the sort of comics that I want to make. I do like existing in this kind of mass market, but one that still has some teeth to it. I’m writing books for older teenagers, my core market is older teenagers and folks in their early 20s. That is the core of a James Tynion audience book, I think.

And very youthful-feeling 39 year olds like me. (laughs)

James: Yeah. But one of the big things that I’ve always tried to focus on when I build a title is I try to know who my audience is. And I feel like a lot of the American comic business is built on who the audience was and trying to recapture moments in the past. There are ways that you can recapture moments in the past, and then there are ambitious steps to try to capture new audiences and all of that, but it’s using old tricks to get new audiences rather than finding the new audiences where they are. And I don’t have the answers to these questions. I wish I did. But it is just one of those things where…I think there’s something to looking at the most successful books in the world, and distilling a little bit of the energy there. Who’s reading them and why are they reading them? And why is it so much easier for people to read that than the latest superhero saga?

Some of that’s obvious the second you start thinking about it. I think as nerds, we get very defensive at the idea of how impenetrable American superhero comics can be to an outsider. But it is. We all have the family members who are just like, “Oh, you exist in a totally different universe than me.” And I mean, that’s fine. But then it’s just like we are relegating ourselves to be a niche medium. I think that as geeks sometimes we like being a niche medium. But there is an opportunity for growth here and for a much wider audience.

And then you look at the most successful books that have come out of America in the creator-owned space in the last however many years, like The Walking Dead, Saga, I’ll throw Something Is Killing the Children on there now, but it’s just like these books are wildly different, but they’re fun and serialized. They capture what the American business market does best, which is serialization.

Trying to move away from serialization is a mistake for the American market. I think we need to rethink what serialization is. It’s by volume, I think, not by single issue. I think that’s where we will end up. But the most successful series that have come out of our market have been multi-volume series that keep going because once people are hooked, they want to keep following the stories of these characters. The comics format is so good at soap opera, and people love their soap operas. We have to find good ways to deliver them. And superheroes used to do a better job at delivering them, but now we cycle in and out of stories and change art styles and change approaches so often that you don’t know your way into the soap opera and you don’t know if the things that matter in your soap opera today are going to matter five years from now. The trust is gone, so people are going to have to find that elsewhere.

And they’re finding it in manga. They’re finding it in a few long form American comics. But one of the issues is that it’s hard for a company to know, “Okay, is going to have legs to last for five to 10 years? And can we support it before it finds that audience?” Which is why a lot of those series are ones that were stood up by the creators themselves, and then occasionally…if I had walked in the door saying Something Is Killing the Children was going to be 100 issues, even me in 2019 wouldn’t have gotten that deal. Maybe you get 12 issues. But thankfully it found success and then I was able to spin it out from there. But it’s just like it’s really hard.

I do think it’s interesting that one of the things that’s majorly different between the Japanese approach to comics and the Franco-Belgian approach to comics and the American one is that there’s a very narrow spectrum of what American comics can be. That’s even the case in the book market, at times. And I think that the other markets have a much broader view of what comics can be and that is part of the reason why it feels more accessible to people and why it’s more culturally accepted. There are not just five different varieties of stories. That’s an oversimplification, but you know what I’m saying. You can have any type of story in comics, and that’s just the way it is.

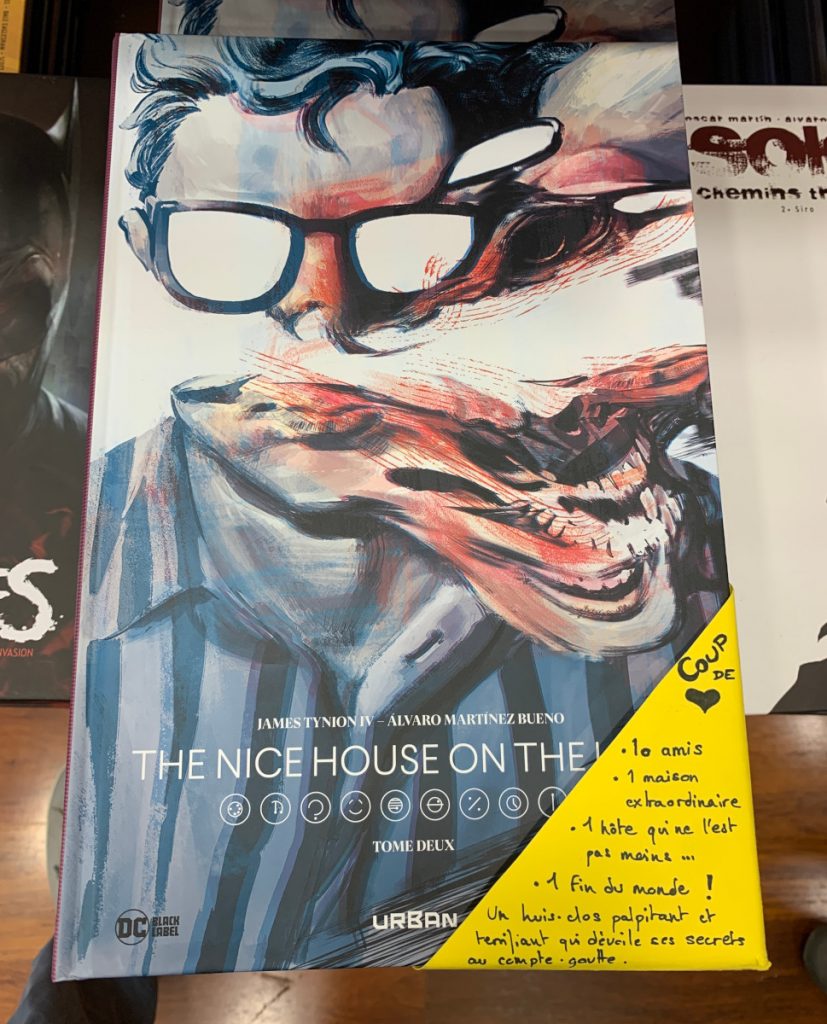

And I think it’s meaningful that the books that you mentioned, like Walking Dead, Saga, Something Is Killing the Children, even something like Chew — or Tony Chu, Detective Cannibale as it’s called in France — those are books that are big successes in France. And part of the reason why I think that is is because they don’t feel like American comics in a pure sense. They feel like they could be anything. They’re just good stories. And I think that because they’re not so rooted in the language of American comics and they just translate better to other markets.

It’s easy to say that American publishers should just publish more genres and it should just have broader ideas of what comics could be. That would be a major sea change in the American market, but it does feel like that’s an important thing too.

James: Yeah. I mean the issue is, and this is always the issue, is we have to start doing the small things now that will pay off 20 years down the line. But the issue is they aren’t going to pay off tomorrow. That is the problem. I think I said in one of our previous chats that it’s like a lot of the major American comic publishers aren’t looking at that long window in terms of growth. They’re looking at the next two years in terms of growth, and that is what’s driving all of their decisions. 10 years from now doesn’t exist. And this is a problem that exists well beyond comics, this exists in every sphere of the American entertainment industry.

See: television right now.

James: Yeah. But the issue is that while we are only focused on what’s immediately in front of our faces, a company like Kodansha is thinking about 20 years from now. They are absolutely thinking about 20 years from now, and they are going to continue making moves because we are, like I said, America and France, those are the next two largest markets. They want to dominate all of those markets, so they are the dominant creative force in comics, and they make really good comics, so they’re going to do a really good job of that. But what are we doing right now to create those footholds that we can build on both in terms of genre and in terms of larger media ecosystems around these books?

Obviously, the biggest thing that manga has that we don’t is the pipeline from manga to anime. And the manga-anime pipeline means that the most successful manga gets turned into anime, and then the anime sells more manga, and then the manga sells more anime. It is like this echo chamber that just builds on itself. And there are lots of reasons why it’s difficult to build that over here. And it would take…I don’t know what it would take, but I wish we had that, man.

I’m just imagining the Tiny Onion anime empire right now where you’re turning everything into animated series.

I want to bring things back onto you. I do think all of this is interesting through the prism of you signing up with DSTLRY, the new comics publisher, if only because its format, the larger size format, the kind of Black Label-ish bigger size of comic…I know that’s something you’ve been wanting to try for a while. But you’re often trying new things. New companies. New ways of delivering comics. New approaches. New formats. I know we’ve talked about this in the past to some degree, but given the nature of how you’re looking at all this stuff and thinking about what could we do with it, how important is experimentation to you as a creator?

James: It’s the most important thing. I need to be constantly pushing myself to try new things out. And I think somewhere that I was talking about the DSTLRY deal, one thing that I pointed out is just the fact that I have a bunch of ongoing comic book series right now that are just going to run for the next several years like Something Is Killing the Children, Department of Truth, W0rldtr33, these are big series that I want to be writing for a long time, so that means I can’t write any more long form series for a while until a few of those wrap up.

So instead, the thing that I need to do to keep myself creatively invested. I always need to be pushing myself in new directions just to keep my mind moving. That’s just how I work as a creator. And I had wanted to find a way to work in this larger format, and they offered me a path to work in this larger format. And then on top of that, looking at the larger international comics market, it’s just a reminder that those larger formats do really well globally. We haven’t quite figured it out. There are obvious exceptions. There are a bunch of big creators who have done successful books in different formats. You can think of the widescreen of 300 or The Private Eye for instance.

But I’ve wanted to play with a different canvas for a while and see what it does to change the pace of the book. And I just love comic book art, so I also just want to see what artists can do on a larger blank page. And so it just felt very creatively fulfilling. But going on this global trip made it a lot less scary to experiment in a new style. That’s because these are books that I believe can find real success here in America, but I also think can find real success outside of it.

Absolutely.

So, we’ve touched on the manga boom, how you felt about seeing how European countries engage with comics, even mentioning Webtoon’s approach. There’s the format differences and the range of genres, as we talked about. Not to make it sound like you’re a computer or something like that, but how do you take all these inputs and turn it into output? Do these experiences and observations change how you view your own work or what you want from or in your own work?

James: The biggest thing it changed was my perspective. It is very easy to get caught in insular thinking when you’re in a small insular business like comics, specifically our corner of comics. And I mean, when I was in superhero land, it was even more insular. I didn’t see the forest for the trees sometimes in terms of what was happening in the larger trends. And the second I stepped outside of that, I felt like, “Oh, I’m seeing the bigger picture of the American market and what’s happening in these stores and what books are connecting with people and which ones aren’t.” And then going globally, I ask the same question in every single shop that I go into, which is, “What’s selling the best?” I am always interested in the answer to that question.

Every shop has a slightly different culture, every country has a slightly different culture, and the answers are wildly different, but they’re always interesting. And it just shows that there are no hard and fast rules, which is reassuring to me because I am not satisfied with the market that exists here.

I am 35 years old. I want to be working in this industry for the next however many decades of my life. I am in a rare position to make some big moves here and there to shape the kinds of comics that I want to exist in the world. And I feel really strongly that there are more big swings that I can take. And having the perspective of the global market as the ground that that game is being played versus just specifically our little corner of the direct market.it feels wildly important to me.