The Comics That Made Them with Faith Erin Hicks

The comics you read and the comic experiences you have early on in your life often form the building blocks of your relationship with the medium. Obviously what you’ll enjoy expands from there, but for readers, those earliest experiences can be enormously influential on you going forward. It’s the same for our favorite creators. Some of those foundational elements can define the interests or views of writers or artists in the future. This interview column is all about those, as I chat with creators about five of the biggest influences and inspirations from the time before (or while) they were working in comics. This is The Comics That Made Them.

Part of the fun of doing this interview series is to see comics from a different point of view. To see the stories that certain creators find inspiring, even if I’ve never read or even heard of them before. That’s the beauty of comics. It’s a big world, and the inspirations that hit can come from anywhere at any time. That said, I always thought it’d be a lot of fun to find someone whose roots were very similar to mine, if only to see what kind of conversation that might turn into.

It’d be a great one, it turns out.

That’s because it turns out cartoonist Faith Erin Hicks – the person behind Ride On, The Nameless City trilogy, Nothing Could Possibly Go Wrong, and more, as well as one of my very favorite comic creators – and I have a similar background when it comes to foundational comic experiences! That shared background resulted in a fantastic conversation exploring why she loved each of her choices, what they meant to her as a storyteller, and how influence can come from anywhere, even places we as outsiders might not expect at times, as well as the exemplary nature of each of these picks. We popped on Zoom recently and had an extended chat about all of that, and what made these five picks so important to her as she was growing up and coming up as a cartoonist.

You can read that wonderful chat below. It’s been edited for length and clarity, and it’s open to non-subscribers, so please enjoy. If you do, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more like it, because the site is entirely crowdfunded, with reader support funding the work that I do in putting pieces like this together.

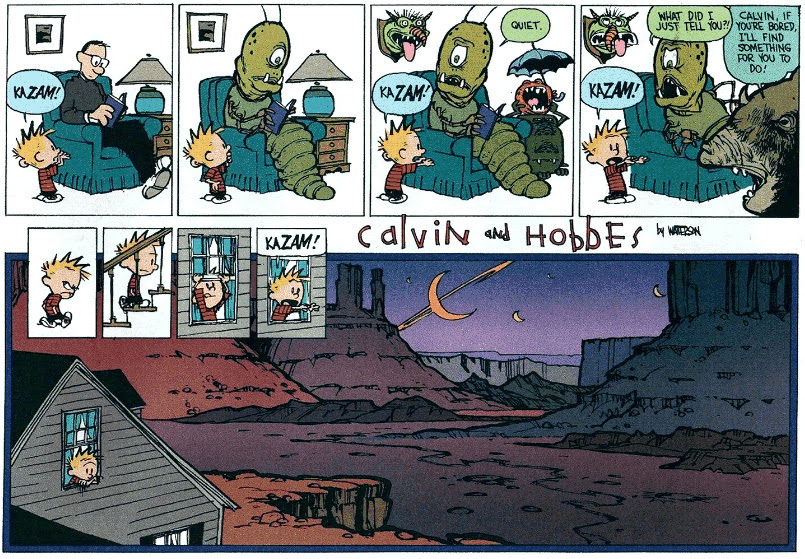

I wanted to do this in chronological order, or at least my perception of chronological order, because you may have engaged with them in a completely different order. We’re going to start with the newspaper comics from the 1980s and 1990s, like Bloom County, For Better or For Worse, Calvin and Hobbes, and The Far Side. Save For Better or For Worse, I was also all about these comics growing up, but I’m curious as to what made newspaper strips one of your selections?

Faith Erin Hicks: The biggest deal for me was access. I was a kid in the ’80s and ’90s. It’s crazy to think about how much the industry has changed and how much easier it is to get comics nowadays. But when I was a kid, there were very few graphic novels available. Marvel, DC, Image, and all the publishers that existed at the time weren’t really into publishing their books in trade paperbacks and libraries weren’t into buying them.

I grew up in a very small town, and I did not have a local comic store where I had access to comics. So honestly, a lot of my comic reading was newspaper comics. I would read them in newspapers, but then also getting the collected editions of For Better or For Worse, Bloom County, Calvin and Hobbes, and The Far Side. I also read a lot of Doonesbury, mostly because Doonesbury has fun stories in it, and I was really interested in comics as storytelling. I would go to the library and check out the collected editions. For the longest time, that was my main access to comics. So that’s really where I began.

Growing up, I read newspaper strips all the time and had the collections. I remember there was this one bookshelf that my parents had that was down this weird hallway, and it had Garfield and Bloom County and Calvin and Hobbes and all the collections of the comic strips. My first “comic books” that I read were the Marvel Transformers comics, and in my mind, those were different. When I was growing up, I didn’t even actively think of newspaper strips as comics, despite the fact that comic strips are absolutely comics.

Faith: It was probably pretty similar for me. Growing up, newspaper comics were something else entirely, both because the horizontal format and the way that they told stories. And I remember being desperate for comics to read, but what was available to me was just not very much. The few times I got my hands on an issue of X-Men or whatever…I remember finding a stack of X-Men comics at a flea market and buying a huge stack of them for five bucks. And it was so exciting to actually have comics. I could not tell you what actually happened in those X-Men comics. It was so confusing because the X-Men in the ’90s…

It was craziness. (laughs)

Faith: Yeah, I think that’s the general consensus.

Everyone is somehow related to Cyclops and might also be some version of Jean Gray that we don’t know. It’s just bonkers.

When I was a kid, I remember my parents loved going to auctions and antique stores to see if they could find something cool, and there would always be random boxes of comics that no one paid attention to. It was like $5 to get these 50 comics, and they’re almost all The ‘Nam. The fact that I could buy in bulk was so important. But going back to it, the access thing is interesting. That access is why newspaper strips were so important for people growing up at that time. In a lot of ways, for kids who didn’t have giant allowances, it was the totality of our comic book world.

Faith: Yeah, I absolutely agree.

So when you were first reading these, were there ones you enjoyed more than the rest, but also sort of ones you just knew were “better?” Or were they one and the same in your mind? Did something like Calvin & Hobbes and Bill Watterson’s work stand out as amazing, or was it just funny and fun?

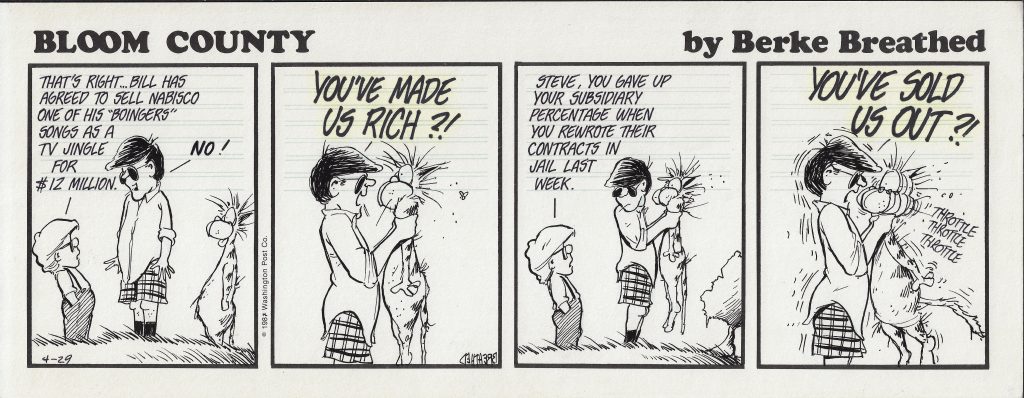

Faith: I was always very aware of the artwork in Calvin and Hobbes. It was so different from what other comics looked like. I found it so interesting to look at. All the details he put into his work stood out, even on a comic page — which is printed on newsprint and compressed many different ways. I also really enjoyed the artwork in Bloom County. And for me, there were certain comics that I was attracted to, and then other artwork that I just absolutely hated that I never read. There was a strip called Shoe or something where the character was a bird, and I remember really not enjoying the artwork and every now and then, I would browse it…but it never attracted me the way that the artwork in Calvin and Hobbes and Bloom County did.

I also really liked how Doonesbury and For Better or For Worse looked. For Better or For Worse is always an interesting one to go back to, because I feel like Lynn Johnston doesn’t get enough credit for her draftsmanship. I think her drawing is actually really good. She draws a variety of characters and draws them very well and portrays stories in newspaper comics that we don’t see very often. They were groundbreaking for their time. I liked her work a lot. I feel like with The Far Side, the point of it is that the artwork is so “ugly,” but it’s not. It’s well drawn, but the characters are always are always…

Frumpy.

Faith: Yeah, frumpy and giant noses and horn-rimmed glasses and that kind of thing. (laughs) But that’s the point, and that’s why it’s so funny. The visual appeal of that comic, you might say, on paper is less than Calvin and Hobbes. But it works so well with the comedy that Gary Larson is doing. It’s perfect. I wouldn’t change a thing about it.

That’s one of the funny things about comic art in general. I remember talking to an artist about Dog Man and Dav Pilkey once. This artist was like, “Oh, it’s just terrible.” And I told him, “He’s not trying to do what you do. He’s trying to speak to kids with his art and he’s telling the story. He’s very effective at what he’s trying to do.” Think about Bill Watterson. Calvin and Hobbes isn’t necessarily what he would do if he was trying to be an artist of a high regard or something like that, but it’s what was necessary for that strip. It’s interesting to see how these artists morph their own style to fit the type of story, or in The Far Side’s case, these simple strips. Those shapes make sense for that strip.

Faith: Yeah, absolutely. I remember reading a Far Side book where Gary Larson talked about the stress he had drawing and how he thought his artwork was poorly done. I remember being shocked by it because I thought his artwork was so great. It works so well for The Far Side, and yeah, he’s not going to go off and draw Bone. He’s not going to go off and draw Monster. 1 But his artwork works so well for what he’s doing.

There’s a real lesson for cartoonists as a whole there. Find where your artwork works. I’ve found my own little corner of comics doing emotional stories for teens and tweens, and I feel like that my style of drawing really works for those kinds of stories. I’m probably not going to ever draw Batman. (laughs) And that’s fine. We’re all uniquely suited to different jobs. And I think Dav Pilkey, Jeff Kinney, all those amazing creators whose work is universally beloved by this entire generation of kids, they do their work well. I look at what they’re able to produce and I don’t know if I could do it because I don’t think that my art style is particularly suited to that.

When you sent me your list of five, this one made a ton of sense because your cartooning style feels like it has more in common with the expressiveness of comic strips than the single-issue comics at the time. Do you feel like your art has roots in these comics at all?

Faith: I don’t know, because I drew as a kid, but it wasn’t really an interest that I was pursuing at the time. I feel like I seriously got into comic-making and pursuing art pretty late. So I feel like the art that influenced me probably came after, once I aged out of those newspaper strips. So definitely Jeff Smith and Bone, which I started reading after the newspaper strips. But when I was younger, drawing was just this fun thing. I didn’t think about improving my work. I didn’t think about art as a career. It was something that came to me quite late.

One of the interesting things about this though is…we’re going to talk about Jeff Smith’s Bone next and then later webcomics from the late 1990s and early 2000s. Comic strips were a huge influence on Jeff Smith, and I imagine to some degree they were a big influence on a lot of the creators that were working on webcomics then. So, while comic strips are not an active influence for you, they may have played a part in a subtle way.

I also don’t think comic strips get talked about as often as they should as influences within comics. But there has to have been an enormous influence from them, outside of Milton Caniff or the ones people do talk about it.

Faith: Yeah. I mean, now that you’re bringing it up, I’m like, “Maybe, I should include them as an influence,” because they were pretty much all I read for the first however many years of my life. Those and Tintin and Asterix. You’re absolutely right. It is strange how newspaper comics are regarded now. Maybe it’s because newspapers are considered this dying medium or something like that. Maybe they’re considered frivolous. But yeah, it’s like we have this one towering titan of the industry, Bill Watterson, and then everyone else doesn’t get talked about that often, which is very strange.

That’s one thing I was surprised by. When you’re a kid looking at newspaper strips, there’s a hierarchy in your brain, even though you don’t think about it. You’re like, “I’m going to read Calvin and Hobbes. I’m going to read The Far Side. I’m going to read this.” I always skipped over For Better or For Worse, because I think in my head, it was more “real” than these fun adventures that these other cartoonists were doing. But the funny thing is, I was just looking over some For Better or For Worse strips, and you’re right, the art in there is fantastic. It’s interesting how I think the craft is slept on sometimes, besides with Watterson who everybody likes.

Faith: Yeah, I absolutely agree. I feel like Lynn Johnston doesn’t get credit for the storylines that she introduced to the comic page. I remember when she had a character come out as gay. Newspapers canceled her strip. People sent her angry letters, saying, “How dare you put this gay person in my family-friendly comics?” or some bullshit. That happened before a lot of the huge diversifying of comics and graphic novels that we’re seeing now. I don’t think she’s given enough credit for introducing these storylines to readers who might also not normally read comics.

I remember when that storyline was going on with the character of Lawrence coming out as gay, and my local paper moved the strip from the comic page into…I think it was the politics section or something like that, which is crazy.

That’s a wild move.

Faith: I want to say it was the ’90s, but it’s just like, of course, we can’t have children realizing the gay people exist.

Last question on the strips. Did you get all of the Bloom County jokes at the time? I loved it, but looking back on it, I feel like I understood 30% of the jokes.

Faith: Oh, my God. Yeah, that comic, it’s like a fever dream trip through the ’80s.

I had no idea of what it was talking about most of the time, but man, that comic strip is so fun. Just the chaos of it. I feel like it’s another one of those strips that’s a little bit forgotten maybe because of what came after. Berkeley Breathed did Bloom County for many years, and then he stopped and came out with Outland and then Opus, which…my personal opinion is that they were not nearly as good as Bloom County was. So I don’t know if maybe that dulled people’s opinion of the strips overall.

But I love the drawings and even if I didn’t understand what was going on, I still found it really funny.

It is funny how Opus and Bill were completely marketed to children. I remember being like, “I’m going to read about this awesome cat and this penguin,” And then I read it, and I’m learning about all these random ’80s political figures that I don’t even know. (laughs)

Faith: Who’s Casper Weinberger? Who’s Oliver North? (laughs)

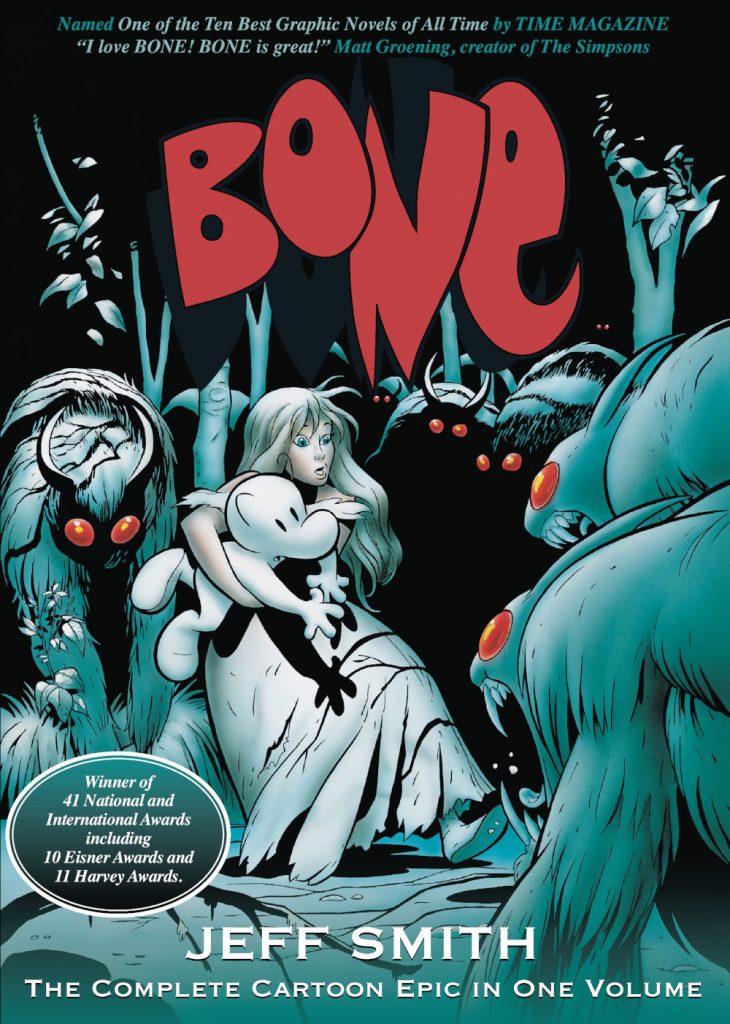

Let’s get to Bone, another one of my favorites. I would say it’s generally one of the most beloved comics around. The interesting thing about it is it’s had different lives and jumps in fandom over its different iterations and releases. It started out with Cartoon Books where it was self-published as single issues. Disney Adventures published it for a while in its little magazine. Trade paperbacks started coming. There was the one volume edition release, which came against later at Scholastic. There were color versions Now it’s been sold millions of times. I’m curious as to when you first read it…was it the one volume edition you have? Was it single issues, trades, or something else?

Faith: I found a copy of the third volume on a rack at my local chain bookstore, and I picked it up and was just like, “What is this?” I’d never seen anything like it. It must have been the late ’90s, because I believe there were seven of the Cartoon Books, black and white volumes out. Jeff Smith was still in the process of writing and drawing the finale, so there were still single issues coming out.

It took me a while to find the books. I don’t know why my local chain bookstore had a copy of this book there, because I didn’t see copies of it anywhere else in any other bookstore. And Amazon existed, but not really for Canadians. It was still really expensive to order things online. It took me a couple years to buy all of the collected volumes, and then I would buy them off eBay, because that was one of the few places I could actually find them. I didn’t have a local comic store. It was so complicated. I just started collecting the black and white collected editions and then collected what was left of the single issues.

I also bought them in the color edition, but I prefer the black and white. That’s how I read them originally. The color editions are great, because they’re a lot more accessible for children, but Jeff Smith drew them to be black and white. That’s what I personally prefer. Years later, they released the One Volume edition and I just picked it up, because I have to own it in every different edition. (laughs)

I sometimes wonder whether your preference of the color or black and white version really comes down to which one you engage with first. I imagine that’s a big part.

Faith: Yeah, I agree with that. I just really like the way how he draws in black and white. I love his heavy blacks. It’s so beautiful. I remember for a time really trying to ink like that with those heavy blacks, and I don’t think it really works for my style. I have more of a lighter inking style now. But he is a huge influence on my work.

What made it stand out to you at the time? Because for a lot of people, jumping in on a third volume might seem insane, but at the time, you often didn’t have a lot of other options. But clearly something clicked with you to the point where you were like, “I have to track all this down.” What was it?

Faith: Part of it was the artwork. I just found his artwork incredibly appealing. But also it was the female characters. I was a young woman interested in comics at the time, and I think it was the late ’90s, getting into the aughts, and comics were not very appealing to young women who liked comics at the time. I think Oni Press was starting to publish their work, and SLG Publishing also existed. So I would seek out work by those publishers, but they didn’t have a lot of fantasy, action/adventure stuff, which is the genre that I enjoyed at the time,. I still do.

Jeff Smith presented this magical, amazing fantasy world that had two very interesting female characters. It had Grandma Ben, and then it had Thorn as well. And he also drew them in a way that was very appealing to me as a young woman who was interested in comics. God, actually, my library had a digital copy of Battle Chasers by Joe Madureira.

Oh boy.

Faith: And I still think he’s a good artist. I think there is something very charismatic and very appealing about his artwork, but the way he draws women, it’s rough. It’s rough, man. I remember reading Battle Chasers when it came out, thinking, “Yeah, it’s action and adventure, and oh God, there’s Red Monika. Oh well, we’ll just enjoy the rest of the comic, I guess.” And it’s fine. I’m not saying that that’s wrong or anything. If you want to draw a giant booby ladies, God bless, but when it’s the only thing available for you to read.

That’s the thing too. There were characters, but they weren’t really characters that were kind of aimed at people like you, if that makes sense.

Faith: Yeah, I agree with that.

You’ve rebought Bone in multiple formats, so it’s clearly something you really love. Has what you love about it evolved over the years at all? Do you feel like you’ve grown to appreciate different things about it as you aged and gotten further into making your own comics?

Faith: No, but that does happen to me. I do appreciate different things about a work as I grow as a person and as a creator. But to be honest, I feel the same way about Bone as I did when I first read it. It’s like this amazing adventure is so well-drawn. I love the characters. Nothing has changed, to be honest.

I think the thing that you’re tapping into here is that Bone has always had this timelessness to it.

Faith: Yeah.

That’s one of the things that makes it such a rare book. I had Jeff Smith on the podcast, and he talked about how people who were in his line as teenagers at San Diego Comic-Con came later on as adults with their kids who were reading it too, and all of them love it the same way. And I think that’s because it’s just so timeless. It’s like Miyazaki or the best Pixar stuff where it can hit everybody at different times, but you just feel it in the same way throughout your life. That’s rare.

Faith: I absolutely agree. It is really rare because, when I go back to comics that I’ve enjoyed 10 or 15 years ago, my opinion of them does change when I read them with the eyes that I have now. Bone…it’s such strong work. There’s such artistry in it. I think it’s fine that Jeff Smith has moved on to other projects. I really enjoyed RASL as well. I wish he’d return to fantasy again. I feel like there’s something about the way he tells a character based-fantasy story that is just incredibly appealing to me as someone who’s a fan of the genre.

I wanted to ask about the tone. One of the most amazing things about Bone to me is how it can switch between being so funny, but also so serious at times, and it’s so dark, and it’s so light, and it’s so many other things depending on the moment. Sometimes multiple things at the same time. That’s really tough to do, and it’s something I think you do really well yourself. Do you feel like that part of Bone was something you found inspiring as a storyteller?

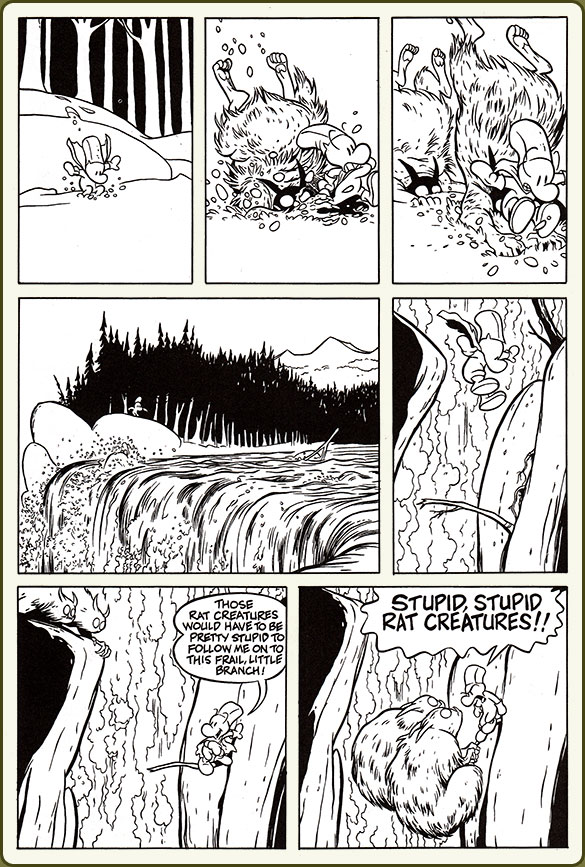

Faith: What works so well about the humor in Bone is that it’s all very character based. And that’s something that I personally really enjoy. I don’t necessarily enjoy jokes that aren’t related to characters in my comics or in whatever media that I’m consuming, but Bone, the funniest moments, Fone Bone being on that little tiny stick jutting out of that cliff, where he’s like, “Oh, those rat creatures have to be pretty stupid to come over on this little tiny branch,” and then the next panel, “Stupid, stupid rat creatures.” What a classic moment. And it’s entirely character-based. You have a smart character being like, “Well, surely these stupid characters wouldn’t do this stupid thing.” And then the stupid characters do that thing, of course. And that is something that has absolutely influenced my work. I’m a big fan of character-based humor, and I feel like all the humor in my books is character-based.

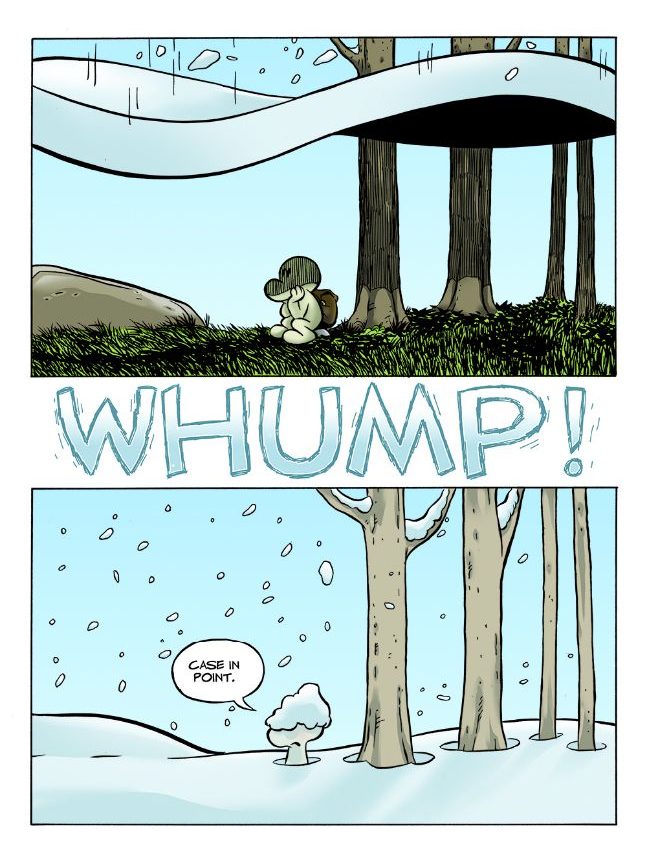

One of my favorite little comedy beats is the final page of the first issue. It’s just where Fone Bone is sitting on the ground…I think somebody earlier says something about how winter comes really quick, and then all this snow just drops on his head and it’s so perfectly drawn.

Faith: So great. (laughs)

That’s part of the reason why Jeff Smith is so brilliant. It’s the marriage of everything together in this perfect package. This is the perfect way to realize that moment, and it just kills.

Faith: I know he worked in animation for quite a few years. I have animation training and grew up loving animation. And maybe that’s another thing that I didn’t even think about it until now. But that’s another thing that really appeals to me about his artwork. It looks very animated. That scene with that great comedic moment about snow just falling. You can absolutely see that as an animated scene.

And it’s something that’s just very visually wonderful.

For people who are reading this, I think it’s important to distinguish that you’re not saying animated in the sense that it’s a cartoony style. You’re talking about the motion element to it, right?

Faith: Yes. And the storytelling, I remember asking him about how he did storytelling decompression on the page, because he has a lot of decompression in his work where you see a character running through a forest, and it’s not just one panel, it’s seven panels of that character running through the forest. And I had mostly seen that style of decompression in manga, so I thought maybe he was influenced by manga. He said he wasn’t. So I assumed that that particular style of storytelling came from his animation background. I shouldn’t put words in his mouth, but yeah, it’s something that really struck me.

His art was a big influence on you. Are there specific things you can point to that stood out and carried with you as you’ve moved on in your career as a cartoonist?

Faith: Inking with a brush. I still do that. Before I really got into Bone, I would ink with pens basically and always really struggled with inking. My drawings didn’t look very good. But when I discovered Bone, I think I read Jeff Smith doing an interview online where he talked about his drawing and his inking, and he mentioned using a brush. And I was like, “Well, I hate inking. I hate how my artwork looks when it’s inked. So yeah, I’m going to try using this brush.” And I still use it. I don’t use the same kind that he uses. I remember he mentioned in the interview how he used Winsor & Newton Series 7, and I used those for a few years and then switched to Raphael Kolinsky, which I like much better. I like the shape of the bristle.

I’ve inked with a brush for my entire comics career, pretty much.

It’s kind of funny how those very specific things can be carried forward. I normally imagine people would expect Jeff’s influence to be something like his character acting, because his character acting is unbelievable and you’re also very good at it. But the brush stuff…that’s such a huge impact because it turned something you didn’t like into something that you like and are good at.

Faith: Yeah. To be honest, I feel like I’ve seen so many online fights about how the tools that aren’t magic and how the tools don’t make the artist. But also, “Don’t ask me what pen I’m using, ask better questions,” and that kind of thing. I agree with that argument on principle. Of course, a brush is not magic. A brush is not going to make you a good artist.

But for me, at least, finding the right tool had a huge impact on my work. And I feel that way about all of the art that I do. Finding the right tool can be incredibly helpful. It doesn’t make you a great artist. It’s not magic. But it can be incredibly helpful. So yeah, I’m always happy to talk about my brushes. (laughs) I love talking about the tools that I use, because this one interview that he did had such a huge impact on my work.

That’s amazing.

Well, I think I’m going to break my chronological streak just so we can split up the two manga books. This is the only comic that I haven’t read at all from your selections, which is Hiromu Arakawa’s Fullmetal Alchemist. I know it’s a classic manga series, but I’ve never read it or even watched in anime form. What made this one of your five?

Faith: Her artwork is absolutely stunning. And she’s really good at fight scenes.

Bone has amazing fight scenes. Monster has amazing fight scenes. But there’s nothing like how she draws people doing battle. So this one, if we’re going chronologically, Fullmetal Alchemist was probably the comic that I read last from this list. I picked Bone up quite early in my career. Monster came late, but I feel like it was right when I started getting published, so the late-aughts. Fullmetal Alchemist, I feel like it didn’t come to it until 2012 or something like that.

I’d had a few books published. I was starting to become more established in my career. But I guess seeing how she approached action and how she approached characters kicking butt and just the dynamic way that she drew, it was really influential on The Nameless City as a whole.

I read Fullmetal Alchemist and I was like, “Oh my God, I want to do something like that.” And obviously, the North American comic book market doesn’t really allow for a 27 volume series. Hiromu Arakawa, she has assistants. She has a whole infrastructure to support her monthly manga, which I don’t necessarily have. But yeah, I read it and I was like, “Shit, I want to do that. I want to do something like that.” It was one of the main influences on The Nameless City.

Bone was very long series. Fullmetal Alchemist was a very long series. Monster, not quite as long. I don’t remember how long it ends up being, but around nine perfect editions or so.

Faith: Yeah, there’s nine, and then there were 18 of the original small pocket-sized manga.

So if that’s the shortest, it’s still pretty long. Do you feel like these types of stories also made you want to tell a longer form story with The Nameless City?

Faith: Yeah, absolutely. I remember before Nameless City, everything I’d done had been standalone. I was desperate to try something bigger. I really wanted to do fantasy. I actually wanted to do Bone. So I was talking to First Second and pitching them, “I want to do Bone. I want to do a character-based fantasy,” and that kind of thing. They were hemming and hawing about it. But then I started reading Fullmetal Alchemist and I was like, “Oh, I want to do Bone, but also Fullmetal Alchemist.” I didn’t tell them that.

I wanted to do something where I could develop the world and make it complicated in a way. Not that real life is not complicated. It is incredibly complicated. But I wanted it to be different from the world that we live in a fantasy world, because I really enjoy fantasy as a genre. And I didn’t want to draw school lockers, because I’d been drawing a lot of realistic fiction. I just wanted a new challenge, wanted something new, and the Nameless City was a result. And then I came out the other side of that and was just so exhausted and so burnt out.

I have to say though, manga complicated is definitely a different type of complicated than normal life complicated.

Faith: Yes, it is.

Monster…that’s a very complicated life.

I did want to ask about her art, because you talked about how the action scenes really hit you hard. What was it about those? Is it the energy? Is it the storytelling of it? What was it?

Faith: All of it. The energy. The storytelling. It isn’t something that I see all the time in manga. Obviously, it varies from creator to creator, but her particular storytelling is so dynamic and also very easy to follow. It’s also, in a weird way, grounded in reality. Obviously, these are people with magical powers, but you believe it when they’re flying through the air.

There’s something in the way that she draws that it’s just like, “Yes, I know that that could happen in real life, and it’s the most exciting and dynamic thing ever.” My background is in animation, and solid movement and dynamic interactions on the comic page…it’s a still medium, but if you can convey movement in a way that works for the reader, it’s rare.

It’s a thing I can’t quite put my finger on, but I feel like it’s very difficult and she just nails it every time.

That’s an interesting connection between all the books we’re talking about. Even the comic strips are rooted in animation to some degree. The sense of motion is a very consistent element in the ones that really stand out to you, and it seems like something you’ve really tried to nail in your own work as well.

Faith: Yeah, I’d agree with that. It’s imagining the images in my head that I want to put on the paper, and they’re not still images. It’s movement. Especially with Nameless City, there’s a few fight scenes in the third volume where I had them in my head for years, and trying to put them down on the paper was very challenging. I certainly didn’t succeed to the level that I hoped to, but I still worked incredibly hard and I’m very proud of what I did. But yeah, it’s just trying to get that movement on the page, and I feel like some cartoonists, they can really do it. They can really nail it. And I aspire to be them someday.

It’s not the same thing as action, but the animation element ties into your character acting, which you are very good at it. It’s the same concept of the before/after, connecting actions≥ I’ve had conversations with artists about drawing punches where the right way to show a punch isn’t to show the punches, it’s to show the before and after. You want to convey that sense of motion. It’s the same thing with character acting. I don’t know if those two ideas are often connected when it comes to the way that people talk about art. They are rooted in the same place in a lot of ways, I think.

Faith: Yeah, I agree. It’s so weird trying to bring movement into this still medium. I think about the movement of the scene in whatever I’m drawing, be it a fight scene or…I’m just looking at Pumpkinheads here and this girl is turning her head and this girl is jabbing her friend with an elbow. That’s all movement, and you’re trying to convey that in a medium that has no movement. And I feel sometimes maybe I approach comics this way as a push back to the comics that didn’t really resonate with me when I was younger. So a lot of superhero comics, I found them very static. So it’s more illustration than what I would think of as sequential art.

I totally know what you’re saying. Especially when we were coming up like the ’90s, this isn’t me diminishing the art anyway, but it was very posed. And it wasn’t really about energy. It was about looking cool, and looking cool is cool. And I certainly thought it was cool at the time, but it’s just a different kind of emphasis.

I wanted to ask one last question about Fullmetal Alchemist. This came to you around 2012. Part of the reason I placed it where I did in this breakdown is because 2000 was a big manga boom. Did you find that manga helped you find more of the stories that you were looking for as a fan of comics, but also as a storyteller?

Faith: So to be absolutely honest with you, I missed the manga boom in the aughts. I don’t know why I didn’t have friends who were into it. I feel like every now and then, I would see a volume of One Piece at the library and I would pick it up and read it. But to be honest, I really didn’t get into manga until the late-aughts when I found Naoki Urasawa and Monster. I was very ignorant about it. I was just like, “Oh, it all looks the same. No backgrounds, characters with big eyes and small mouths.” I was very ignorant.

I missed it completely. And then what was I reading in the aughts? I feel like I was just reading Bone and then maybe stuff published by Oni and maybe some Image stuff. So alternative, I guess. And then I finally found Monster, and then it just broke open manga as a world to me. And I was like, “Holy shit, manga can do this? Oh my God, I didn’t realize I was so foolish.” And finally, I came to the conclusion that manga is actually really great.

I was going to save Monster for last, but I never read manga until I read another series from Naoki Urasawa, 20th Century Boys. And when I read 20th Century Boys, it wasn’t like I wanted to read it. It was like I was compelled to read it.

Faith: Yes.

I was reading it from the library because it was 800 volumes, and I was like, “I need to get this book.” People kept checking out the next one I was going to read. And finally, I was like, “Screw it. I am buying all of the volumes.”

Faith: Nice.

As soon as I read 20th Century Boys, I started reading more and more. And it goes back to what we were talking about with comic strips earlier. I think, to some degree, manga feels different for comic readers who hadn’t read it before. You almost need something to unlock it for you. For you, that was Monster. For me, that was 20th Century Boys. But I do think you almost need that gateway into manga, and once you get there you’re like, “Oh my God, why have I taken so long to get here?”

Faith: Yeah, absolutely. It is different visually. Obviously, it’s comics from a different country with a different visual language, so you do have to learn that language. I mean, thank God, for Naoki Urasawa. I feel like his work is so accessible. His panel layouts are very intuitive. It’s very easy to follow, and he doesn’t use a lot of the shorthand that you see in Shonen or Shōjo. He doesn’t use a lot of the shorthand, because it’s not for kids. It’s for adults, so he doesn’t need to use that. It’s not appropriate for the stories that he’s trying to tell.

His work is just so accessible. He introduced me to the language of manga, and then I felt like I had the basics so I could go and explore and read work that’s more complicated and more steeped in the language of Japanese comics. So yeah, it’s a good gateway drug.

I feel like his library of works has a different answer for every person, basically.

Faith: Yeah.

If you told me that the first manga you read and loved was Master Keaton, yeah, I would absolutely believe it. Or Asadora! or Pluto or whatever. Of course, Pluto. I mean, Pluto’s amazing.

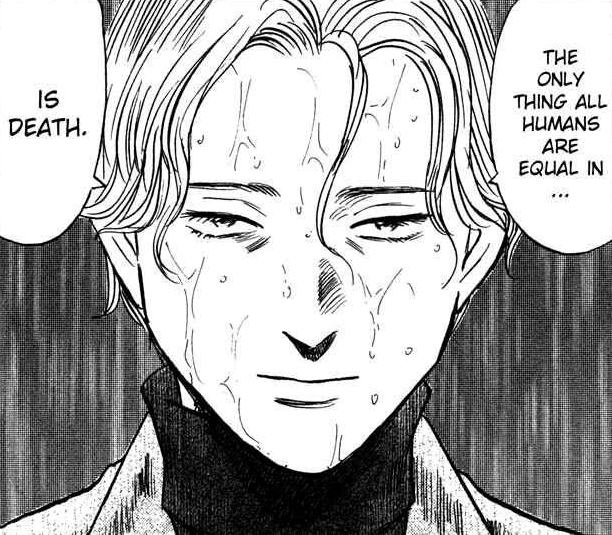

I love that you, a person who primarily works in all ages, young adult, middle grade-type comics, you started with the series about a Japanese surgeon in Germany who gets involved with a serial killer he once saved. (Faith laughs) So I have to ask, what makes Monster your pick? Is there something specific about it you connect with?

Faith: So it is my pick because it’s my first Naoki Urasawa. It’s actually not my favorite. My favorite is actually Pluto.

But Monster introduced me to manga and was my introduction to Naoki Urasawa. But when people ask me about my seminal influences, I’ll name Monster over Pluto because I’d read all of Monster before Pluto or 20th Century Boys started coming out.

But it was the artwork. He’s really good at drawing men. He’s really good at drawing suits. He’s really good at drawing everything. And he’s also really good at decompression on the page. I’m just flipping through it right now, and there’s the confrontation between Tenma and Johan in this parking garage where Tenma sees Johan kill for the first time. It’s maybe 20 or 30 pages long. And it’s just the suspense…he’s so good at it.

And I really enjoy his choices for bleeds or safety cutoff, and I like doing bleeds and keeping the artwork contained within the safety cutoff. I feel like his storytelling choices of when he does a bleed and when he does a safety cutoff are always really thoughtful. That was something that was a big influence on my work.

It’s so weird. It’s these little tiny things that you pick up from each individual artist. With Bone, it was learning how to ink with a brush. With Monster, it’s decompression and when to bleed or not bleed your panels. And then for Hiromu Arakawa, it was the dynamic fight scenes.

I love the fact that Johan, a horrible serial killer, is this very pretty man in the vein of Howl from Howl’s Moving Castle.

Faith: Yes. He’s so beautiful. Tenma is too. I love the way Urasawa draws his nose. He gives him this very beautiful long nose that…I remember I would copy panels from Monster because at the time I was struggling in my artwork. I was going through a phase in my artwork where it was very influenced by cartoons that I was enjoying at the time. It wasn’t really working. I was just trying too hard and trying to force a particular drawing style that just wasn’t working.

So when I saw Monster, it was like, “Oh, I can do something that’s more grounded in realism, but still has a simplicity and a cartooniness to it.” So I don’t have to give up the cartooniness. I just have to make it more solid. So that’s something that I really love about his work. It’s the way he draws figures and faces. They’re fairly straightforward. But there’s a solidity and a realism to it. It really works for me.

Also, Tenma, he seems like he gets more attractive the more rugged he gets. (laughs)

Faith: In the beginning he’s got this goofy little haircut, and then later on, he gets long hair and stubble and he’s all manly. It’s like, “Yeah, good stuff.” (laughs)

You’re like, “Tenma, your life sucks, but it’s really working for you, man.”

Faith: I know. “You look good, man.” (laughs)

This is a pretty dark series, even relative to Urasawa’s other works. It’s funny though. I think in our minds, as readers, maybe we have this idea that if a person tells lighter or more welcoming stories then maybe they won’t love dark stories. But we talked about how you love Alien, and Alien…that’s not a happy movie.

Faith: No. It’s one of my absolute favorite movies.

Yeah, it’s fantastic. But Monster is definitely unlike what your work normally is. Is there something about that darkness that you find to be a particular draw for you?

Faith: This is actually something I’ve thought about a lot lately, because I am a creator who does comics primarily for middle grade and YA audience, but then there are comics and stories that I want to enjoy as an adult, and that’s where my interest in horror comes from. I’m actually not the type of person that typically likes a serial killer story. I don’t find serial killer stories to be that interesting outside of Monster.

But I don’t read a lot of middle grade. I read more YA than I read middle grade. And a lot of it has to do with the fact that this is where I work. I work in these younger genres, and I want to be aware of them and what other creators are doing within the field, but I don’t necessarily read those genres for fun and for enjoyment. I am someone who finds certain types of horror genres very interesting, but I don’t necessarily see myself making those kinds of stories. I just enjoy them personally as a reader. I am actually a huge wimp when it comes to horror. Horror really scares me. I’m always sitting there with the blanket pulled up to my chin being like, “Oh.” If I just fast-forward through this scene, I’ll see what happens and then I’ll come back and rewatch it, and it’ll be okay.

I think that the stories that can be told in the horror genre, can be incredibly interesting and incredibly subversive. I’m thinking about Barbarian.

Oh, my God. Yeah.

Faith: There’s a horror novel that I really enjoyed, and it’s called My Heart Is a Chainsaw by Stephen Graham Jones. He is a First Nations writer, an indigenous writer, and it’s about a First Nations teenager who is basically fighting off a real-life slasher using her knowledge of slasher movies. And it’s incredible. I really enjoy horror being told from the perspective of someone who is perhaps a minority or perhaps someone who’s been oppressed by the system. I just feel like it can be an incredibly subversive and interesting genre. I do, however, think there is a lot of crap out there. (laughs)

Which is where it gets it’s terrible reputation.

That’s the funny thing about horror though. Because it’s so cheap, it’s often quite profitable. So the churn is constant, but there are some real gems.

There’s a level I can’t get to, though. I’ve never been able to do Hereditary or Midsommar.

Faith: Midsommar is fine, I think. I didn’t find Midsommar scary at all, which is very shocking for me because I find everything scary. Hereditary, oh, my God, that one was rough.

If anything about that movie shows up, I’m just like, “I don’t even want to know.” My sister-in-law, she reads Wikipedia entries about horror movies because she wants to know what happens, but she doesn’t want to watch the movie.

Faith: I did that, too. (laughs)

I did that with Midsommar. I can’t do that with Hereditary. I just don’t want to know what happens in that movie.

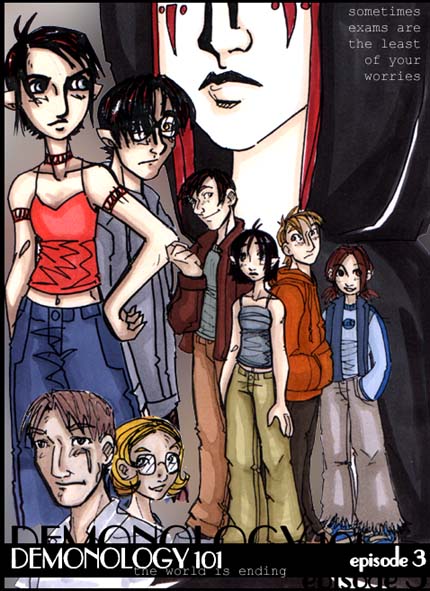

To close, we’re going to talk about my favorite curveball from your list. It’s a great pick. The online comics community of the late 1990s and the early 2000s. Not the comics themselves, but the online comics community. You described it via email as “Such a fun and weird time for comics, and it’s how I got started making them.” Can you take me back to that time? What was that like? And when you were talking about that community, what did it entail?

Faith: For me, personally, it mostly involved a lot of lurking and a lot of hiding on LiveJournal. I was quite young at the time and I was a little bit feral and very socially awkward, so I had a hard time interacting with people even on the internet. But I really enjoyed what was out there. I enjoyed being an observer of the community because it felt like people gathered on message boards, on LiveJournal as well, those early days of social media.

I feel like message boards were the big place. I remember lurking at a bunch of different ones who are either now very problematic, because they were run by Warren Ellis, or long lost into the ether and I can’t even remember what they were called. But it felt like this very interesting time for comics, because there was a lot of amateurs sometimes with very few art skills, like me.

And there were no gatekeepers. If you had a story to tell, you could just shove it onto the internet. And because there were so few comics online, even if you weren’t a good artist or a good writer, you would find an audience. That was something that happened to me pretty early on. I did this webcomic called Demonology 101. It started in 1999 and then finished it in 2004 when I graduated from college. And when I finished, it was over 750 pages long. This was my very first webcomic, so I’m completely unable to write and draw short comics at all. At the time, I feel like anyone who was a professional cartoonist viewed putting their work on the internet as…not shameful, but “Why would you do that if you’re a professional?”

I remember there were online image galleries where people would post snippets of the latest Image Comics and that kind of thing. Not the entire comic. Just panels. And I would scroll through the galleries and stare at them because it was one of the very few ways I had access to published comics, because I didn’t have a local comic store. And then the Penny Arcade guys still had day jobs and their comic, which was basically a newspaper strip with X number of panels that would update three times a week. And then you would see people like Bryan O’Malley, all of a sudden, start up a webcomic and everyone would rush to read his webcomic because his work was incredible, even back then. And then he’d abandon it a few months later. (laughs) I feel like that happened three times.

Other creators like Jen Wang or Erika Moen, a lot of women, Dylan Meconis, Clio Chiang. And some of them went on to have real, legitimate comics careers and win Eisners. And others went on to work in animation and work for studios like Disney and that kind of thing. But everyone was there. I was actually talking about it with a friend and she described it like the punk music scene. (laughs) Obviously, it’s not nearly as cool as that or as influential as that, but the internet kind of connects you and you all have this commonality, which is you’re good at art and you’re good at writing and you may as well make comics because there’s no one there to tell you no. And that was how I got started.

It’s so weird to think about now. It was so long ago.

Obviously, there’s downsides to it sometimes, but there was a lot of magic to that time it seems. There was a lot of people finding each other. There’s a lot of people finding their own voices and getting their work out there and everything. One thing I often see from creators is they’ll talk about how important it’s to find your community. To find peers that are your own age to grow up with. Was that a big part of what this was for you?

Faith: A little bit. I feel I actually found my community later. This seems very strange to me nowadays, but I feel like it’s probably the years of therapy and working on myself talking. I am a much more confident person and someone who can socialize in a normal way with other human beings. I felt really lost at the time. When I was doing my comic, I was a little bit ashamed of it.

Demonology 101?

Faith: Yeah. I felt like it wasn’t good enough and I never mentioned it to anyone in real life. I never went to comic conventions or anything like that. And the friend that I was talking to today about her experiences in the aughts comic community, her experience was incredibly different. She’s like, “Yeah, I went to all these cons and I hung out with my friends and we all went drinking and to karaoke,” and I was like, “Man, that seems incredible.”

And for me, while I was doing that early webcomic, I just felt I wasn’t good enough. That’s absolutely on me. Nobody made me feel that. If anything, I would say that the readers that I had during those early years were incredibly kind and incredibly encouraging towards me in a way that the internet has lost at this point, and I just think is really sad, because I couldn’t imagine being a young creator trying to start out making comics today.

Nowadays, people are such jerks online. You see someone pouring their awkward heart out online through their drawings and their original characters, and I see these people and I’m just like, “Oh, I was you, 20 years ago.” But if you post that stuff on Instagram, all you get is people yelling at you and telling you that you suck.

So, yeah, I feel like my community actually came later after I had started getting published and hooked up with First Second. And I’m very grateful for the community that I have now of other creators and other people who work in this graphic novel sphere. But at the time, I wanted to do the comic but I struggled to actually interact with the community that was around me. But I was very aware of it and I really watched it from the outside. Thinking back on those awkward early twenties years, it’s like, “Oh, my gosh, Baby Faith.” (laughs)

You already talked about this a bit, but I imagine part of it is the fact that it wasn’t just you being a fan or being a part of it in conversational sense. You also had skin in the game. You had your own comic. And so I imagine that kind of changed your feeling because you weren’t just putting yourself out there as a person. You were also putting yourself out there as a creator who hadn’t done anything like that before, which probably made it even more intimidating in a lot of ways.

Faith: And I felt everyone was better at making comics than I was. That was probably a lot of it. I was just so intimidated by the other creators that I saw online. I remember Jen Wang’s comics or Vera Brosgol’s comics, and they were so much better than mine. “Oh, my God, they’re so good…why would anyone want to read my comics if they can read theirs?” That’s the Two Cakes! thing. Have you seen that comic?

No.

Faith: It’s just a little meme comic where you have one person putting their very small handmade cake next to another person’s beautiful three-tier masterwork. And it’s like, “Well, my cake isn’t nearly as good as this other cake, so why would anyone want to eat my cakes?” And then some person comes up, and is like, “Holy Shit! Two Cakes!” (David laughs) So that’s the excitement. So instead of being like, “Well, this is a bad cake and this is a good cake, instead, it’s like, “Oh, Two Cakes!”

I was not reading comics during this stretch. I was going through high school, so I was definitely in my pure awkward phase.

Faith: Oh, God. Yeah. Solidarity.

Looking back…I don’t know when he came in there, but it’s funny seeing somebody like John Allison doing Bobbins which led into Scary Go Round and then by the time he gets into Bad Machinery, it’s like that that Vince McMahon meme where, at first, he was a little interested and then it just keeps evolving and by the end he’s like, “Oh my God.” (Faith laughs) By the time John gets to Bad Machinery, you’re like, “My God, John Allison’s just a really good cartoonist.”

You could go back through everybody’s work, Jen Wang, Vera Brosgol, Bryan Lee O’Malley, everybody like that, and I bet you could see this just steady evolution. That’s one of the interesting things and one of the tricky things I bet about being part of that is everyone was watching that growth live, and…that’s a lot.

Faith: Oh, it’s rough.

You brought up the environment today. I think that online structures of the past can be romanticized, but it did feel a lot more siloed and maybe close-knit. It wasn’t everybody in there and everybody was pulling in the same direction and doing the same thing.

My version of what you went through is I was part of a forum for a video game. We would meet up with other members of the forum and we’d play the game together, and we were friends because we all did this thing. It wasn’t even that we were all the same. We were all different ages and ethnicities and genders and everything like that. We were just tight because we did the same thing. And it’s interesting where that bond around this commonality was so strong versus today where it’s social media, our bond is we’re all on this same platform. And there basically is no bond.

Faith: Yeah. I definitely don’t want to look back on the internet of the aughts with rose-colored glasses. There was still plenty of drama and harassment and awful people. I guess what really did make a difference was the fact that the internet was so much smaller. So to have a webcomic with a hundred readers was, “Oh my God, so many readers.” Right?

Yeah.

Faith: Whereas now, people, comics on Webtoon have readers in the millions. So obviously the number of assholes to nice people is significant.

Insane.

Faith: I do think that there’s something to the community aspect. I think about Instagram, and it’s like most of the people that I follow there are people who do comics and I’m interested in their comics specifically. I feel like social media, you can find your little corners, but it’s not the same. It’s not the same as having a dedicated forum. Maybe that’s what the future of the internet is going to be. It’s like everyone all of a sudden starts splitting off into these little Discord servers where this Discord server is dedicated to Dragon Age and this Discord server is dedicated to Bone comics, and that kind of thing.

Are you talking about those two from personal experience?

Faith: The Dragon Age one, for sure. (laughs) I have a little Discord server with some friends, and it’s like all we talk about is Dragon Age.

I love it. It’s funny, I was actually talking to a creator recently who was like, “I’m waiting for creator websites to come back.”

Faith: Yeah. I feel like they should. Despite the fact that everyone uses social media, I feel like you need to have a website. You need to have an internet hub, because who knows when some narcissistic billionaire is going to snap up what has basically been the comics community message board for the past 15 years? Twitter has been incredibly important to the comics community, and now, we don’t know its future. So yeah, I do think it’s actually important to have a website.

There’s something to be said about how having to rely on these other platforms is pretty difficult.

We’ve talked about this a bit, but do you feel as if this community and experience really changed your path as a cartoonist?

Faith: I think so, because it did give me access to a particular group of cartoonists who were very different from what was being published at the time. And eventually, they became published Eisner Award-winning cartoonists. And I don’t think I would’ve had access to them if they weren’t on the internet. Maybe I would’ve found their work. Maybe I would’ve found The Prince and the Dressmaker decades later when it came out, when First Second published it. But if Jen Wang hadn’t been posting our artwork online back in the aughts, how would I have ever found that?

I also saw people drawing in this style, so I felt like I was in the same territory as them. It wasn’t this heavily muscled superhero style. It was usually a clean line style, sometimes influenced by Bone, sometimes influenced by manga. Even though I was bad at being a person and bad at talking to other humans (laughs), I still felt like my artwork could fit within that world if I could make it good enough.

That was definitely the challenge of the next 10 years. It was working hard and becoming a much better artist, because I just felt like everyone was so much better than me. I don’t think I’d be here if it wasn’t for that community and if not for just having the internet available as a hosting service for such a long time. It allowed me to draw thousands of pages of comics and develop my voice and my art skills. That was really important.

Thanks for reading this interview with Faith Erin Hicks. If you’d like to read more like it, consider subscribing to SKTCHD to do just that and support the work I do.

Naoki Urasawa’s manga series, which we discuss later.↩