The Comics That Made Them with Jordan Blum

The comics you read and the comic experiences you have early on in your life often form the building blocks of your relationship with the medium. Obviously what you’ll enjoy expands from there, but for readers, those earliest experiences can be enormously influential on you going forward. It’s the same for our favorite creators. Some of those foundational elements can define the interests or views of writers or artists in the future. This interview series is all about those, as I chat with creators about five of the biggest influences and inspirations from the time before (or while) they were working in comics. This is The Comics That Made Them.

A comic creator loving comics isn’t exactly news. A lot of them get into the medium for the love of the game. But sometimes, making comics can burn out a little bit of that love and turn reading them into homework. It’s an understandable feeling, and one more creators share than you might realize. But if there’s one creator who doesn’t carry that with them, it’s writer Jordan Blum. The co-creator of Hulu’s M.O.D.O.K. series and Minor Threats over at Dark Horse Comics — both with writer Patton Oswalt — doesn’t just love making comics, he loves comics. He has a complete collection of the first volume of X-Men, he has a seemingly encyclopedic memory of many of his favorites, and he’s a regular reader of comics both new and old. Case in point: Within the conversation I’m sharing today, he actually referenced multiple recent releases as comps for what he was talking about. 1 It’s a passion he carries with him to this day.

That love of the medium made him an ideal person for The Comics That Made Them, an interview series that is all about the comics that inspired a creator’s love or approach to the comics they now make. If anyone was going to have some very specific takes, it was going to be Blum. And you know what? He did not disappoint! He offered a quintet of single issues — not runs, graphic novels, or entire titles, but individual comics — that he could point to as ones that were particularly influential for him as both a reader and a creator, particularly on Minor Threats. That specificity led to a wonderful a conversation, one where we discussed each of his choices, the impact they had on him, artists with singular voices, reading above your age level, and a whole lot more. It’s a good one.

You can read it below. It’s been edited for length and clarity, and it’s open for non-subscribers. If you enjoy our chat, maybe consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more conversations and features like this.

You’re the first person who has ever picked five single issues, which is interesting. Do you think you’ve always thought about comics in single issues first? Is that the way your brain works as a reader?

Jordan: This is more the foundation of how I became a reader… I didn’t start going to a comic store. That came later in life. This was probably at the pharmacy or the supermarket or someone handed it down to me. There’s something about treasuring that one issue and going back to it and reading it. Half of these picks I don’t even have the covers on them anymore because they came on vacations and stuff with me. Or if their covers are on, they’re hanging by a thread.

I don’t always love this argument now of, “You have to make everything super accessible,” or “This has to be everyone’s first comic,” or “There’s too much continuity.” The appeal to me was being thrown into the deep end and being like, “I’m going to read this 100 times until it makes sense and then learn more by hunting down more comics.”

Any of the confusion would quite often be incentive to go back and find the other comics to learn what you missed.

I do think that’s the funny thing that your picks are a part four of a story, another part four, the second issue of a run, and a part five of a story plus an adaptation of a movie. A lot of people would think that anyone reading these issues would be lost. I wasn’t. They absolutely worked and I think that’s pretty amazing.

Jordan: Yeah, I think good writing lifts all these books up. And art, I should say. Some of these are very art driven. But all my favorite writers are able to tell a full story within an issue even if it’s a part of a larger whole. I think that’s influenced the way I write as well, especially for television.

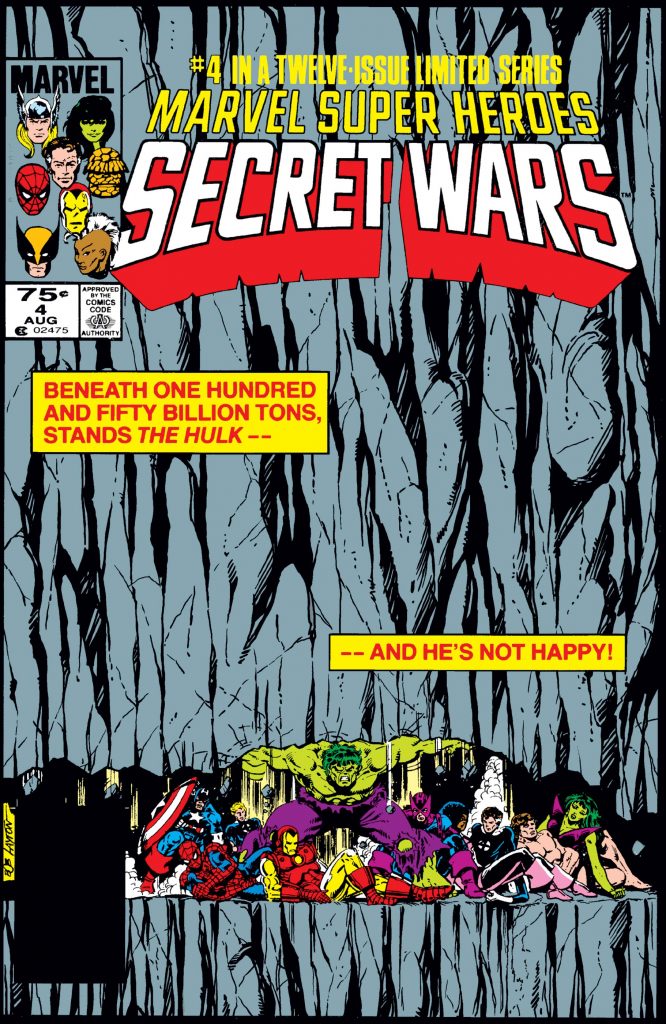

Your first pick was Secret Wars #4 from the 1984 Secret Wars, written by Jim Shooter, art by Bob Layton, inked by John Beatty, colored by Christie Scheele, and lettered by Joe Rosen. What made this one of your picks?

Jordan: It was foundational. The idea of a shared universe was cemented with this one.

I think everyone has their individual Spider-Man comics or Batman comics or whatever. And as a kid, the idea that the X-Men live in the same world as the Hulk and this and that…that being the genesis of Jim Shooter’s story, where he was like, “Let’s throw them all together, have them all fight, we’ll sell a lot of toys.” It worked like gangbusters for me. I bought all the toys. I bought as many of these issues as I could. It was just that foundational element of a universe of comics being a fully lived-in place.

I was two or three or something like that. I don’t think I bought it when it came out in the stands. I might have gotten it in some sort of pack or something in the 1980s, but it was love at first sight. I wanted to live in this universe. I wanted to come back here every month and be with these characters. Plus, it has one of the most iconic covers.

It all starts with the cover. This is at the beginning of my history with comics. As a kid, you’re drawn in by the cover — and I think even as an adult still too — but to have all that negative space of the mountain and then the Hulk holding it up at the bottom with all the heroes about to be crushed underneath it, it was like, “What is this? I have to find out what’s happening.” So, it was cover first, and then as I dove in. The X-Men are here. The Avengers are here. The Fantastic Four are here. I’m in the middle of this giant crossover that makes no sense to me, but I get it. It’s simple.

All the toys are here.

I think the thing that gets brought up the most about Secret Wars these days is the fact that it was done because they wanted to sell toys. But I think one of the weird appeals about this book for me, and part of the reason why this issue works in a standalone way, is that it very much reads like a person playing with toys. And I mean that in the most complimentary way possible.

It has these different groups, and they intermittently go up against each other, like Enchantress and Thor are together, and then suddenly, they get mashed together with all the villains and Thor’s like, “Oh, hell no, I’m going to beat the hell out of all you guys.” It’s this very pure and fun and simple concept that just works. I’m not going to pretend like it should be on everyone’s best of lists or something like that. But I can see why people really loved it.

Jordan: Well, it reverberates in that it created the crossover. This predates Crisis (on Infinite Earths). There had been tiny crossovers of characters here and here, but not line-wide crossovers until this point. And to this day, it holds up in that it gave you what it promised, which is a giant war with the entire Marvel Universe. Galactus shows up in it. Klaw and random characters like Molecule Man are a huge part of this storyline. And The Wasp and The Lizard and all these characters that may not interact in the greater Marvel Universe are forced to come together, like you’re saying.

But beyond that, as I’ve gone back and filled in my reading of that era, there’s real lasting effects. This is what breaks up Kitty and Colossus. This is the Black costume, which is going to change Spider-Man comics forever after this. This is The Thing leaving and She-Hulk joining the Fantastic Four. There were real ramifications to the storylines that continued on.

To this day, that’s what makes a good crossover. You want a great hook and a great way to see all these characters interact. But you also want to know how the books will change going forward. I hate this terminology, but “Does it count?” I think if you’re going to invest in a crossover, it should affect things on a bigger level.

You said that you read this years later. Did you read the previous three issues of Secret Wars before you read this? Or was this issue your gateway?

Jordan: This was my gateway and then I tracked a few down. So I would always just miss issues. It would be very sporadic. I think I owned maybe four or five of the 12 ultimately and then years later I tracked down the trade and read the whole storyline. But it almost didn’t matter because like you said, you could jump in and you’re like, “Oh, this is the one where Thor fights Absorbing Man. Got it. And then the X-Men team up with The Fantastic Four and Magneto’s here, but he’s a good guy.” You didn’t need the previous issues. You just knew that this week’s big fight was this and there were some stories slowly moving forward with The Beyonder.

Your brain fills in the rest.

I really like the fact that Molecule Man drops a mountain on the heroes strictly because he is trying to impress Volcana, which is his entire arc there. It’s fantastic. That goes back to feeling like you’re playing with toys. You’re just doing these big crazy things. But I think that that’s tying into the idea of events being bigger and everything. This book was, I don’t want to say, the first time you had mountains being dropped on people or things like that. But it did feel like it was a book that just went for big swings just because that would be the cool thing to do. And sometimes, that’s fun.

Jordan: The scale felt right. To earn a 12-issue maxiseries and a toy line and all the things that spun out of it was set up to deliver on the promise. And then going back to what you were saying about Molecule Man, that’s another one of my favorite conventions that, now that you put it in that way, was probably introduced to me in this. Taking a low-level unpopular underdog villain and giving them a moment, showing that every character has the possibility of greatness, a story moment that’s going to last or be impactful.

And it’s funny. I think ahead to the Secret Wars that would come (in 2015) and (Jonathan) Hickman does this all over again in the follow up where all these characters are given their moment. And clearly, this stayed with him because Molecule Man pops up, I believe, in the last issue. He saves Miles, right?

Yeah. He’s essential to the whole thing. He’s the one who’s powering God Doom and everything. And yeah, he does save Miles because Miles gives him a burger that’s three weeks old or something like that, which is disgusting. I love it.

One thing I like about this book too is it’s so loaded with characters, but it has them in digestible groups. The X-Men are by themselves. For some reason, Magneto and the Wasp are together, but it works. The other heroes are together. They have all these different groups. You have the different groups commenting on each other and how they don’t trust each other, even the heroes about the X-Men. That’s great because it’s almost meta commentary on how separated the characters are in the regular universe to some degree.

Jordan: Absolutely.

This had to be one of my introductions to the X-Men, which would become a lifelong love and passion. They’re the Benders 2 of The Breakfast Club of heroes. The bad boys out on their own that aren’t associating with the others at first. There was something dangerous about the X-Men, whereas the Fantastic Foreign and Avengers immediately come together with Spider-Man and everyone. The X-Men were like, “We keep our distance a little bit.”

You mentioned this a little bit before we started chatting about how the stories where you can jump in and just read it as is affected how you think about story to some degree. Beyond that, can you point to anything that this comic fueled in you as a reader and/or as a storyteller going forward?

Jordan: Some of it is find interesting pairings of characters who don’t always go together because that is what this crossover lends itself too. And then less from a writing standpoint but more about building my off my love of superheroes and comics were the toys. I feel like the idea of comics being this bigger cultural thing, where you read these and then the story continues in your own imagination with the toys, I think those coming out at that time and me falling in love with comics and then wanting the story to not end with the issue, but then I had the toys to keep that story going. The comics medium would extend to TV, to movies, to toys. You discover your superheroes in comics but then you can find them elsewhere.

I didn’t know at the time that comics were where this was born. They seemed omnipresent because there was a toy line that went with it. These things were around me in different forms. And obviously, comics became the true passion if you were like, “Would you give up the MCU or your collection of whatever for comics?” Absolutely. That’s always going to be the winner. But at that moment, it felt like there were endless possibilities of where to find the characters and that the stories would branch out beyond the comics themselves.

I do think sometimes people look down on Secret Wars and the whole toy angle. But what’s different from that than me getting into the comics because, to some degree, the Marvel Universe trading cards or X-Men: The Animated Series or the X-Men arcade game. Gateways can come in all different places. I’m not saying that Jim Shooter was doing it for that reason because I suspect that they were just selling toys. Which is great. But it worked out that way.

Jordan: It made sense because this came out in mid ’80s and this is the toy boom of tie-ins to shows. He-Man, G.I. Joe, ThunderCats…

Transformers.

Jordan: So, Marvel had to do theirs and they immediately were my favorites.

I was less of a Transformers fan than I was a Secret Wars fan or a Super Powers 3 fan. I think being able to have access to the comics and the toys solidified my love of superheroes. I was in forever.

And to this day, if I see Firestorm or Doctor Fate, there’s a little bit of excitement in it for me because I think of the toys that brought me in. And the same thing for Marvel. I had a Baron Zemo toy and a Kang toy. So, when Kang showed up in the MCU, I wasn’t thinking about an Avengers comic I loved. I was thinking about my Secret Wars Kang toy that I treasured.

I think what you’re saying is correct that there is this sometimes a bit of snobbery of like, “Well, I was born with a comic in my hand, and that’s the pure way to enjoy these characters.” But we all have different gateways, and mine perfectly timed out with a comic book and a toy line that tied together.

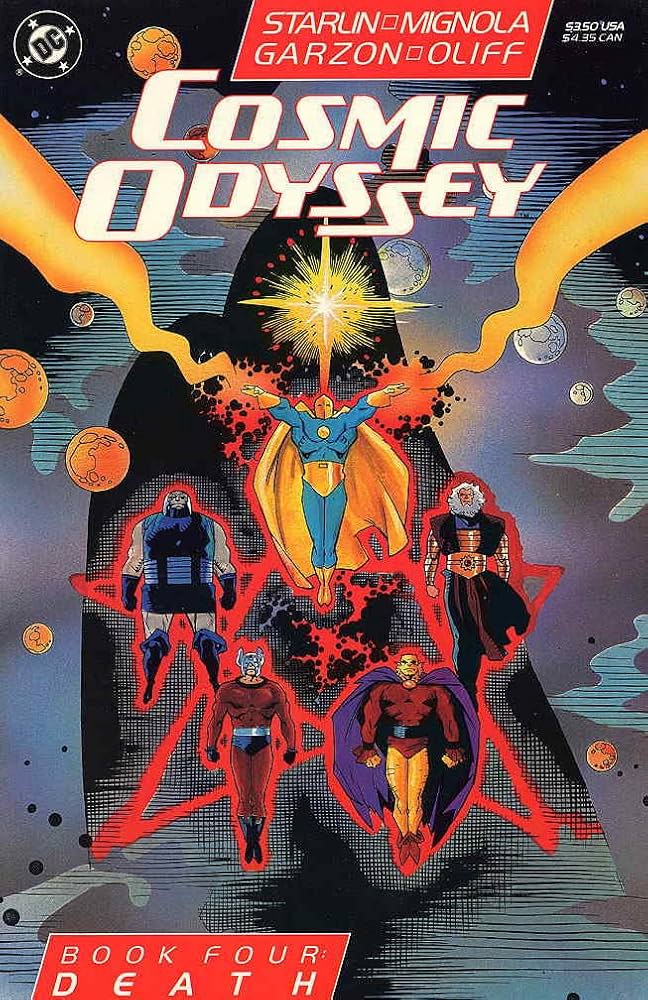

The next book is Cosmic Odyssey #4, which was written by Jim Starlin, drawn by Mike Mignola, inked by Carlos Garzon, colored by Steve Oliff, and lettered by John Workman. I just read this series for the first time last year. I’d always heard good things, but for me personally, Cosmic Odyssey is one of the best-looking comics you can find. What made this one of your picks?

Jordan: If there’s a theme of some of these things I’ve picked, it’s that its where my tastes shifted in my comics journey. If Secret Wars was the perfect thing to give a little kid, Cosmic Odyssey was that promise that was on the books at the time. The “DC is not just for kids” marketing thing they did.

How old were you when you first read this?

Jordan: I was probably six. This is 1988, right?

Yeah, 1988.

Jordan: This is when Tim Burton’s Batman’s coming out (in 1989). This is The Killing Joke. I had all of these because it was, again, “That’s the Joker from Super Powers. 4 I’m going to buy that comic where he’s on the cover.” “Oh look, Doctor Fate from Super Powers is in this Cosmic Odyssey thing. I’m going to buy this book.”

It was such a slap in the face in the best way. I was disturbed by it, like Batman and Forager fighting this guy with a hole in him where you can see his spine. It’s Mike Mignola doing horror stuff in a comic. Green Lantern essentially commits genocide and contemplates suicide until Martian Manhunter talks him out of it. It was heavy, dark things that maybe at six were too much. But I also loved it. It felt wrong to be reading this comic but at the same time, it was challenging and disturbing. I put it away.

At this time, my mom read an article in Time Magazine I think that was talking about…I think it was that Catwoman miniseries that came out where it solidified her as a prostitute in her origin. 5 It was an article asking, “Do you know what your kids are reading?” in Time Magazine. So, she went through all my comics and took a bunch away until I was older. The Killing Joke was taken. Cosmic Odyssey. There were some Captain America issues by Mark Gruenwald with the Watchdogs where they were hanging people. Anything that was deemed inappropriate (was taken), and I would sneak in and try and find them because I missed reading these comics.

But it was that moment of these things can go beyond kid adventures or safe places. They can take you into more adult stories and things that are darker while challenging you with big ideas. It’s Jim Starlin, the king of expanding superhero consciousness, writing mixed with a Mignola who was ahead of his time. It was a wakeup call of, “Look what comics can do as an art form.”

It’s funny…It’s not that the Secret Wars was all pairings, but Cosmic Odyssey was a situation where they literally just paired characters together and sent them on these adventures. You talked about Martian Manhunter and John Stewart, the Green Lantern. That story was the one that really got me because you’re right, John Stewart straight up committed genocide. I don’t want to say it was intentional.

Jordan: His ego got the best of him.

His ego got the best of him.

At one point, in this issue, he’s considering killing himself. That’s a pretty heavy story. Martian Manhunter is not the most encouraging person. He gives the advice that is necessary but you’re like, “Oh, this is pretty intense, man. What are you doing?”

Jordan: He uses his ego against him to get him to not kill himself, which is very clever.

And the other thing that’s amazing, is it like a 10 page or 10 panel grid or something of John Stewart with a yellow gun to his head because yellow is the only way he can…

The weakness.

Jordan: His ring’s weakness. Yeah. It won’t try and stop him. It’s beautifully drawn, but yeah, there’s an edge to it.

The pairings, though. I love the pairings throughout the series. Forager and Batman is just nuts. There are all these different groups that you have for these different missions, and it’s fun seeing all them. Also, you alluded to this with Secret Wars, but a lot of readers who probably read this were discovering characters they’d never seen before in the process of reading this. This was probably a lot of people’s introductions to the New Gods. That’s powerful. That type of thing where it’s any comic can be somebody’s gateway to a new comic or to comics in general, but it also can be a gateway to a new set of characters….I think that’s a really cool element to this series.

Jordan: Yes. I knew Darkseid from Super Powers but I didn’t know the lore. Here you’re getting Lightray, the New Gods, and Highfather. Even Etrigan (The Demon) shows up. It’s all this great Kirby stuff mixed perfectly with your Superman, Batman, your Justice Leaguers, and a few others.

But yeah, I think it disturbed me and I had to put it away. I think those are some of the best comics. I had a similar reaction with Sienkiewicz’s art around this era. It made me uncomfortable. I didn’t like it. When I was a kid, I used to force myself to look at the box art on horror movies until I couldn’t stand it anymore and run away at the video store. Sienkiewicz’s art was like that.

What’s funny is I wasn’t ready for it. I was six. Same thing with Cosmic Odyssey. It just disturbed me. And then coming back as an adult and being like, “Oh my God, this is my favorite stuff.”

This is a true story. I have never read Bill Sienkiewicz comics because I was so scared of his art on Demon Bear when I was a kid. I’ve thought about going back and reading it. There’s a mental block, pretty much. I was offered an interview with him at New York Comic Con a few years ago and I was like, “I can’t because this reason,” and I think the PR person thought I was an insane person.

Jordan: He went from being the artist that disturbed me the most to now my phone background is from his New Mutants art. I went back and reread all of his New Mutants, and that was my gateway into Sienkiewicz. Then I went and did Elektra and the Daredevil stuff. I still need to do Stray Toasters, but it just made me a super fan of his.

But at the time, you couldn’t pay me to read a Sienkiewicz book. I experienced Cosmic Odyssey before Sienkiewicz, and it had a similar disturbing feeling like, “I shouldn’t be seeing this.”

I do want to give one shout out. One thing in the art that really stands out is Steve Oliff’s colors. They are just outrageously good in this book.

Jordan: It’s so different than what Mignola’s stuff looks like now. It’s bright and colorful DC stuff mixed with his very dark, heavy shadows. I got to talk with Mignola at the Eisner (Awards) this year. That was the highlight for me. When I was presenting, I got to meet him backstage and totally did not play it cool. But he was very gracious.

I had to ask about Cosmic Odyssey, this thing that I hold so high, this work of art, and you can tell he doesn’t love digging into anything pre-Hellboy. He’s like, “Yeah, I got my superhero stuff out of the way.” That was kind of what was his attitude was there, and I was like, “You have no idea how much this book shaped me and stayed with me forever.” The imagery still haunts me.

So, same question I had before for Secret Wars. Do you think this issue impacted you at all as a storyteller going forward? As in, the way that you think of story or anything like that?

Jordan: Yeah. I think in a big way, I loved seeing how flawed heroes can be. Especially the John Stewart stuff, that always stayed with me. The idea that heroes can make mistakes and that they don’t always save the day, and they don’t always win, and that there’s complicated stories to be told within this genre. Cosmic Odyssey is a great example of that. Half of them fail. There’s no real win at the end. Evil will prevail. Darkseid will get his hands on the Anti-Life Equation one day.

Even the concept of Anti-Life Equation is so dark and soul piercing that it reinforced that these things can be complicated, they can be rich, they can have a lot of humanity, and there’s a lot to explore here outside of the one-and-done issue.

That’s a great point. For a lot of readers, this might be the first time they’d seen any of these characters lose. A lot of times you think of superheroes as almost infallible because they always win in the end. But in this book, I think Superman and Orion end up being successful but some of the bigger teams, I was surprised that they were actually losing in this book.

Jordan: Batman can’t save Forager. We have the whole thing with the planet and John Stewart. There’s a lot of tough losses. It’s funny. I’m looking back on it and I think what Cosmic Odyssey is, is my representation of DC Comics in that period because I didn’t grow up on Watchmen. I didn’t grow up on The Dark Knight Returns. Those books were for other people. Even Death in a Family was one where it was like, “I can’t believe they’re doing this in a comic. They’re allowed to do this?”

I think DC always felt like the grown-up comic company moving forward to me. I loved both equally, but there was something about the possibilities of what DC was willing to explore at that time.

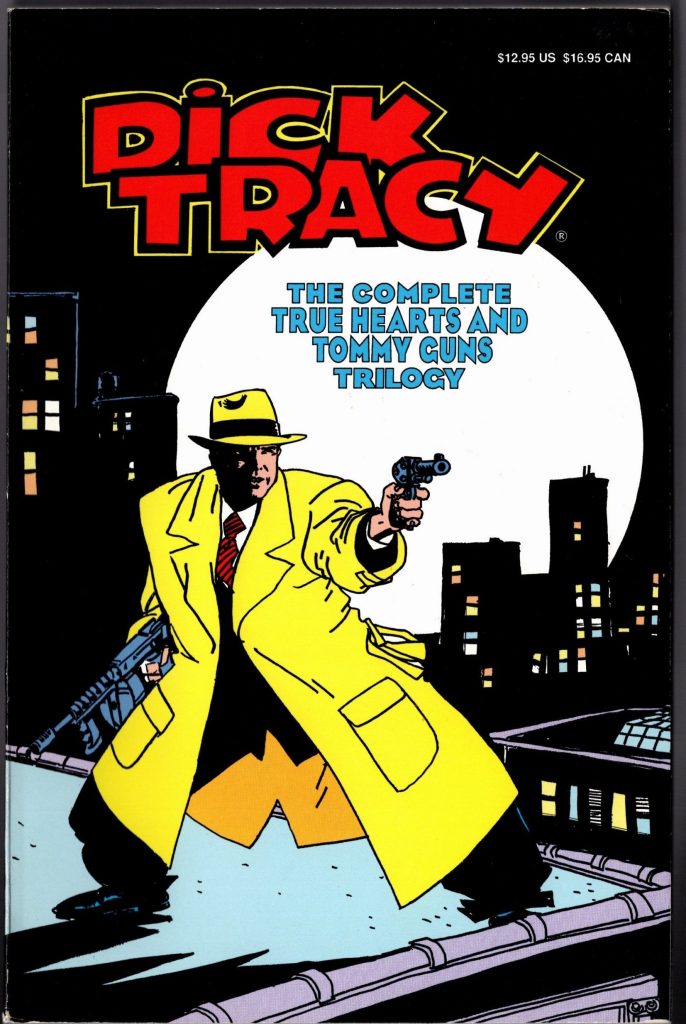

Your next pick is the one comic I could not find. It’s Dick Tracy: True Hearts and Tommy Guns, an adaptation of the movie that came out in 1990. It was written by John Moore with art by Kyle Baker. Sell me on it. Why was this one of your five?

Jordan: I’m going to do a whole thing on the Kyle Baker art because, oh my God, you do need to track this down. It was a miniseries, but this issue is the adaptation, and the others are a prequel.

The third one is the adaptation, and the first two are a prequel, I think.

Jordan: Batman ’89 was a life-changing movie for me. It was a huge fight with my parents, who deemed it inappropriate. I wasn’t allowed to see it even though I had been waiting for this movie to come out, to the point where I read the trading cards and put on a play with my friends based on what I thought the plot of Batman ’89 was based on the trading cards. I had to experience the movie. I finally got to see it and it was like, “Look at what is possible when it comes to adapting comics and translating them to the screen.”

When Dick Tracy rolled around, that became my next obsession. I had no familiarity with the character outside of the movie. That and I want to say Who Framed Roger Rabbit? were like, “Hey, these are noir conventions and you’re going to love these things for the rest of your life.” Those were baby’s first noir. But I was obsessed with Dick Tracy, in particular. I loved the Chester Gould villains. Every villain, like a Spider-Man or Batman villain, they had a visual gimmick. But it was all very much grounded in the world of crime and police work and gang wars and all these things. I needed more.

This was one of the first reverses where instead of loving a comic and then seeing the movie, I saw the movie and sought out the comics. It just cemented that even more that I feel like Dick Tracy is now my white whale of a franchise that I would love to one day work on. It infused noir into almost everything I write. It’s my favorite genre outside of superhero. It was this perfect storm, again, of a comic tie-in to a movie and toys. Minor Threats is a direct line from this.

When I think of the movie, I think about all the colorful characters in this world. And not Madonna as Breathless or Warren Beatty is Dick Tracy, but the villains. All the makeup that was done to make them look like Gould’s art. That builds out the world and makes it feel a lot more special. I feel like that’s what a lot of Minor Threats is. Even something like Barfly…why would you ever consider telling a story about a background character if you didn’t have the love of the colorful characters that make up these sorts of worlds?

Jordan: Yes. And that’s what I was looking for in this comic. When I bought all those prequels, I wanted a whole story about Little Face. I wanted a whole story about Influence or Shoulders. It’s a lived-in world that felt real and comic booky at the same time, and I think that’s what I loved.

And then Kyle Baker’s art was perfect to complement that because he is a cartoonist by nature. The exaggerations that make Pruneface Pruneface and Shoulders Shoulders…he excelled at that. The movie has its flaws but it’s a feast visually. It’s matte paintings for days and color palettes that look like the coloring of comics and it was the closest to a comic book coming to life, even more than Burton’s Batman for me.

And it also helped me understand how the language of comic books can been used. A lot of times in movies and TV, the term “comic booky” is viewed as a negative thing. But to me it became the thing I would chase the rest of my life while working in other mediums.

Again, in Minor Threats…big, crazy, loud visual ideas, big character designs, gimmicks, this and that but very grounded, recognizable things. These are all noir kind of clichés, your dames, your mobsters. It grounded it in a real world but allowed it to be exaggerated and larger than life at the same time. That became the thing I would chase forever in my writing, which is how you make things comic booky.

And writers too. We’ll talk about Grant Morrison later but that’s someone who embraces some of the silliness or the bigness of comics, but always finds a way to ground it with humanity. Dick Tracy is a great franchise that does that, where…that’s a guy who has a giant brow but everything else feels like crime noir. And I love that.

That’s what I love about Batman: The Animated Series, which would come after Dick Tracy. Finding familiar conventions from crime noir and stuff like that and using it to tell a comic booky or superhero story.

This ties into a book we haven’t talked about yet. You had some interesting picks from the art side. One was drawn by Mike Mignola, another was by Kyle Baker, and the one that’s coming later was drawn by Larry Stroman. Three people who I’d say aren’t your traditional idea of a comic book artist, in the sense that they are more cartoonist types. They have an excess amount of style that some people who love Jim Lee or love Walt Simonson might feel uneasy with. Yet they work perfectly for these books.

Do you feel like these stories established what you look for in the comic art as a reader but also as a storyteller?

Jordan: I think so. I think their uniqueness all attracted me when I was younger and then I went through…this isn’t any shade on Jim Lee or anything like that. I was Jim Lee fanatic and still am to this day. His art is beautiful. But I feel like as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come full circle to these artists and have reevaluated what attracted me when I was younger, and it’s a unique style.

I would almost put Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld in with that. It’s less that it’s exaggerated and cartoony and more that it’s instantly recognizable.

No one looks like Larry Stroman. No one looks like Kyle Baker. No one looks like Mike…well, some people look like Mike Mignola, but you know the original article when you see it.

Jordan: Yes. And the same is with Liefeld or Sienkiewicz or anyone like that. There’s something about having an instantly recognizable style that I really like. I’m always looking for something that feels both familiar and different when I’m looking at artists. I always like being challenged by art.

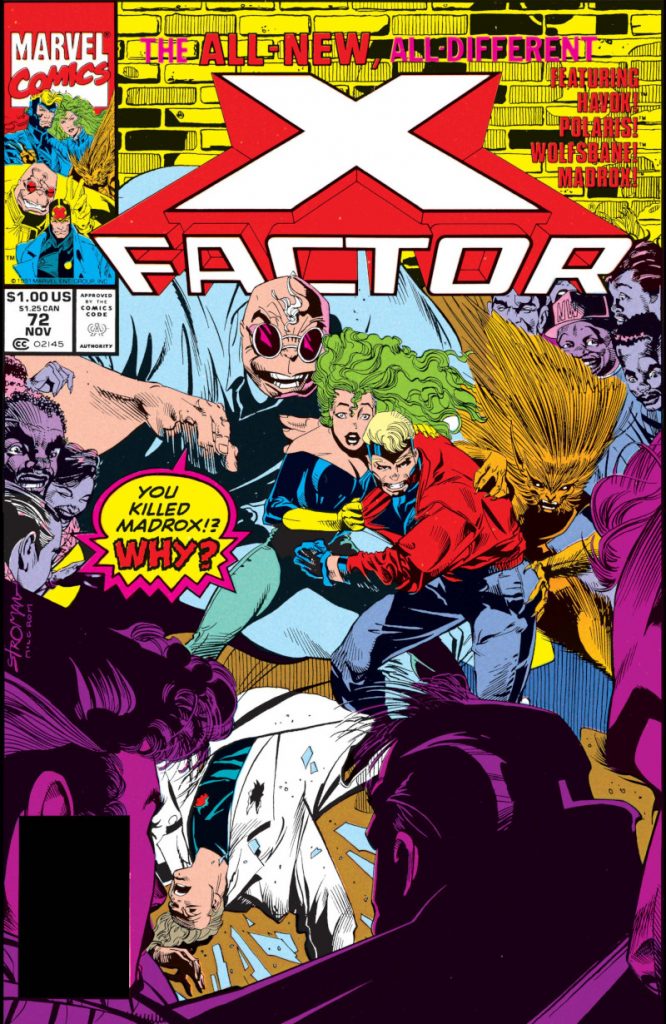

The next book is X-Factor #72 from that title’s first volume. It was written by Peter David, drawn by Larry Stroman, inked by Al Milgrom, colored by Glynis Oliver, and lettered by Mike Heisler. We talked about this a little bit at San Diego, but I did not like Larry Stroman’s art at all when I was a kid. Looking at Stroman’s art now, though, I can see it through completely different eyes, and I actually really appreciate what he’s good at now. This is a great looking comic in a way that I did not give it credit for. What made this one of your picks?

Jordan: I haven’t talked a ton about the X-Men, but the X-Men have been my passion since as long as I can remember. I think I’ve said once before…(my first) was maybe the Revolutionary War annual. I was all in. I bought as many X-Men comics as I could.

This came out around Mutant Genesis, where it is Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld launching X-Men and X-Force. X-Factor was the least…not the least popular, but maybe it’s not as well regarded because it didn’t have, like you said, the hottest art team launching it. It felt different.

It also didn’t have any A-list characters, really.

Jordan: Yes. And I think this book made me realize that I love underdog characters. I’ll take Madrox over Wolverine any day. I grew up loving these characters and always being like, “Why don’t they show up more? They only show up for one issue. Havok’s only here for two issues and he’s out.” X-Factor was taking all these characters that I’d fallen in love with as D-list X-Men, letting them have the spotlight, and then making it comedic, which rarely ever works in comics.

To me, what makes this book so important is the comedy… at the time I read a little (Justice League International). But this clicked for me more. I went back later obviously and read JLI and it’s amazing. But (X-Factor) was my JLI. This was sitcom-y humor mixed in with mutant soap opera stuff. It was seamless to me. I loved having funny characters who were desperately human, and they would later explore that. I almost put in the Doc Samson issue.

#87?

Jordan: Yeah. But I wanted to just use the one that I fell in love with because even that one, #72, I think ends with Madrox getting shot.

#72 ends with Madrox showing up and saying that he’s another Multiple Man. He’s like, “I’m the real Jamie Madrox and the other is a dupe.”

Jordan: Yes. That’s what it is. He got shot in a flashback and then sent a dupe who was killed, or something like that. There’s a giant mystery at the center of this. I missed the first one. I think #71 is where the relaunch actually starts. 6 But here are things I know I love now as a reader: D-list X-men, humor, and highly humanized characters where the X-Men soap opera stuff works best. And it made me a Peter David fan.

The Stroman art was unlike anything else. It had so much energy. Every background character looked like it was a real person he had drawn off the street in New York or D.C. where the book is set. It felt lived in. It was my preferred X-Men. Even though I was an X-Men fanatic and I was all in on the Jim Lee stuff, this was the book I was most excited about. These are the characters I was the most attached to, and that would follow me forever. If there’s a New Mutants #1 or an X-Factor #1 or Havok is leading, I’m the most excited about that book of all the X-Men relaunches.

It was something about…you can do more. You can break the D-listers. You’re not as precious with them I feel like as sometimes you are with A-listers.

Tying to us doing a show about M.O.D.O.K. or doing a Minor Threats book, it’s about these characters that no one else thought to include or pay attention to but in the right hands can become the best characters. Suddenly, that’s what Strong Guy or Madrox was for me.

I’ve talked about this with the X-Men in specific before, but for a certain generation of X-Men fan, Generation X is their team. I think part of it is this might’ve been the first X-Men team that was completely new after you became a reader and so you could claim them as yours to some degree. You know what I’m saying?

Jordan: Yeah. Absolutely.

I related to them more because I was a humorous kid or a class clown. I wasn’t a self-serious person so I couldn’t relate to the militant X-Force.

It’s funny too because they constantly roast each other here, which is very atypical for a lot of superhero teams. Most teams are collaborating, and all the characters in X-Factor are constantly just ripping on each other in this issue, which is pretty amazing.

Jordan: Yes. And I still will always buy a book that has this tone to it. There was one last year that was Red Tornado with a team.

Oh, are you talking about the one was from Steve Lieber and Mark Russell?

Jordan: Yeah.

One-Star Squadron.

Jordan: Yes, One-Star Squadron.

The idea of levity in superheroics…obviously I went on to make a funny show about a supervillain, and even though we thought we were doing a very self-serious crime book, everyone kept saying that the first Minor Threats volume had humor in it. So it’s hard for me to not write those sorts of characters in books without adding in this kind Peter David ribbing each other joking. You can have very serious plots happening but even the characters are a little in on how fun and ridiculous it is to be a superhero.

The last thing I want to bring up about this is something that comes up whenever I read comics from the ‘80s and ‘90s, which have their pluses and minuses, just like comics of today do. But the story density in this issue is crazy. So much happens in it. It feels like an entire arc for modern comics. That’s part of the appeal. It has this sitcom feel but also has this extreme story density and it makes it feel so unique relative to even the comics that were coming out then.

Jordan: You’re getting a full meal. That’s something I miss a little bit, and I think Minor Threats is very reactive to that where…I love a good six issue arc, but if you can do it in four and give me more of a meal along the way…there’s something about packing these things. I think that’s why Grant Morrison is probably one of my favorite writers. You always feel that only the good stuff made it in. There aren’t these long-drawn-out exposition scenes or just conversations. Comics should always be moving. Things should always be happening. I do miss that a lot.

We try to work that into what we do with Minor Threats so there’s no filler.

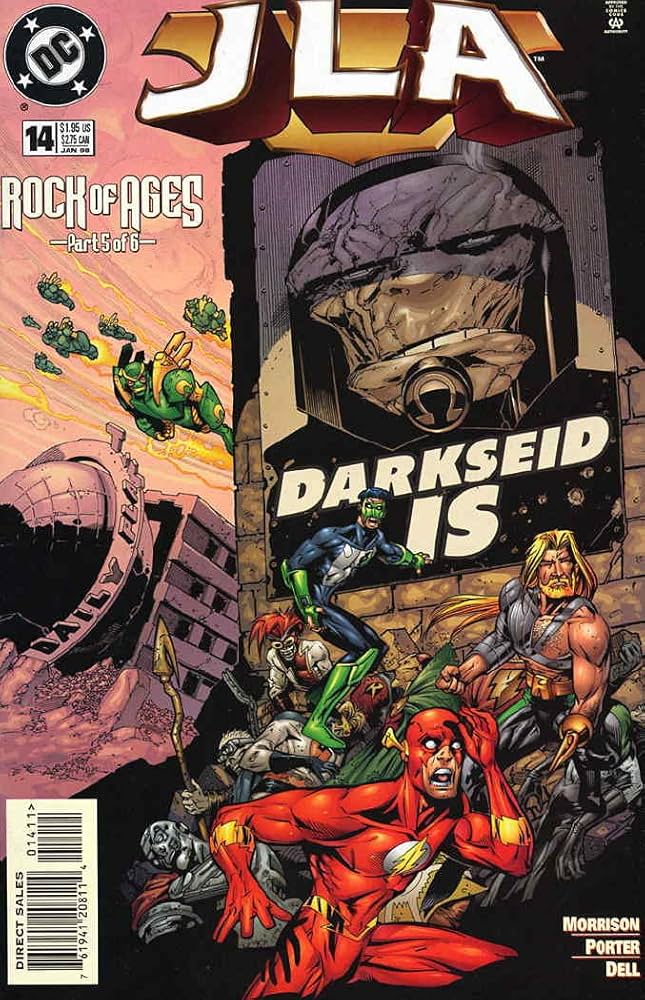

The final book is JLA #14 from the 1997 series. It’s written by Grant Morrison and drawn by Howard Porter. It’s the team that started the book. Inked by John Dell, colored by Pat Garrahy, and lettered by Ken Lopez. When did you start reading this series?

Jordan: #1. I was in on the ground floor.

I don’t think I’d ever read a Justice League book before this. The Wizard Magazine hype for this series was too much to resist. I think I might’ve either started on this arc or the one before. The funny thing is, despite the fact that I think people loved it at the time and it sold really well, I think it’s underrated.

Jordan: Yes. It’s my Desert Island superhero comic. Its entire run. It is everything I love about superhero comics, especially DC, because all these characters have this weight to them. They’re gods. They feel like myths who have come together. When Superman says something, it’s incredibly important. Or Batman is being underestimated and proving why he’s the Batman that we all love. I think every character gets a moment to shine in this run.

That’s why I picked this issue. Grant Morrison loves comics so much that they’re going to give you the best Green Arrow-Atom moment that’s ever been written in three pages. It was this moment of, Darkseid’s beaten everyone and it’s down to Green Arrow and Atom, and Green Arrow fires a flash grenade and he realized…

A flare arrow.

Jordan: A flare arrow, that’s what it was. The Atom realizes that Darkseid’s pupils expand with light. That’s how the Atom’s going to get into his brain and just starts punching Darkseid’s brain.

Any character can have that moment. It’s like with Molecule Man earlier. Every hero has the potential to have the coolest moment ever if written well. If the writer’s creative enough to figure out how to use them. This whole run is nothing but that. It’s realizing that Plastic Man is the most powerful hero in the DCU. Everyone gets their moment to shine. And I was just blown away by this where I was like, “Well, I guess I’m the biggest Atom fan now.”

This is a pretty common pick from this larger run, but my favorite story from this run isn’t even by Grant Morrison. It’s Tower of Babel. I absolutely love Tower of Babel by Mark Waid and Howard Porter and an array of other artists. But the funny thing is that arc is about Batman plans to take out his teammates if they went bad, and Ra’s al Ghul using those plans against them. He has all these solutions for the strongest characters in all the DC Universe.

I feel like Grant Morrison is that version of Batman when it comes to telling these stories, where they can figure out the right solutions for the right characters in the right time. This is a wild oversimplification, but it’s going back to the Secret Wars thing. It’s the peak version of playing with the toys. Reading this, you just realize how good Grant Morrison is at playing with these toys. It’s spectacular.

Jordan: It’s a cleverness and it’s a love of all of superhero stuff. The silly, the serious, the good, the bad, it all counts and it’s all going to be funneled through these characters in these moments, and I think that’s what this book cements. It’s a giant widescreen movie, which became a thing people were chasing in comics for a while. I feel like the Ultimates is almost a reaction to this book in my mind. “We can do that with the Avengers. We can tell big, giant, epic stories.” Each arc does feel like a movie in this, but it’s telling stories in this medium in a way that you can only do in comics.

It’s encyclopedic knowledge of everything that’s come before and honoring that, and then finding completely new ways to tell stories with these characters and create these iconic moments that I feel I’ve never seen before, while also feeling right for the characters.

I’m trying to remember, was it White Martians, then Angels, and then this storyline?

Jordan: Yes. But then there’d be little ones sprinkled in, like Green Arrow alone on the satellite, again being underestimated and using the trick arrow to defeat The Key. It all comes down to the boxing glove arrow at the end. And if you can’t tell that influenced Minor Threats. We have a weapon with a boxing glove at the end that’s used to take out a villain.

But again, it’s a celebration of the Silver Age and the goofier things in very modern storytelling that is winking at it and respecting it and doing something to new with it at the same time.

I love possible future stories. They’re so great because anything goes. You can just kill off characters and it doesn’t matter because you’re sending Wally and Kyle back anyways.

Jordan: Well, that reminds me. I didn’t include it, but I read all the What Ifs from the ‘90s because every issue was like…half the X-Men are going to sacrifice themselves by the end of this. We’re going to do stuff we can’t do in these possible futures. You always get those high stakes and those big dramatic moments that feel amazing, but you can do them because you’re not setting it in the present. This might happen. But look at how epic this can get.

I also love that the whole issue is narrated by the Black Racer, and you don’t find out until the very end, which is awesome.

Last question for you. You said in your email, and I quote, “These picks are pretty random, but I can trace everything I’ve written back to them.” We’ve talked about that a bit here, but with JLA, what is it that you think you can trace back in specific?

Jordan: It’s those visual moments. The Atom going into Darkseid’s head or that trick arrow moment or punching an angel. To me, Grant Morrison knows how to build tentpole moments within an issue. It’s trying to think in the most purely visual way when I’m writing. What are the three or four visuals I’m going to hang this issue on. The moments that make you want to stand up and cheer. That to me that is the perfect comic. When I finish one of those and I’m like, “Oh my God, I can’t believe they did that.”

Grant Morrison to me had at least four or five of those instantly iconic moments in their Justice League run. When I think of it, it’s this Atom moment I come back to every time. This is a reason to tell a story, to have a comic book.