A Quest for the Familiar: Liefeld, Tynion and the Power of Blockbuster Comics

This spring, digital comics magazine PanelxPanel released four “One Shot” essays on a variety of comic-related subjects. Among them was “EXCESS” by Ian Gregory, a reassessment of Rob Liefeld’s 1980s work on New Mutants and X-Force. Gregory’s thesis is that much of what critics have come to deride about Liefeld’s early work forgets the broader context that he was responding to.

It’s an interesting essay. Without ignoring problems in Liefeld’s run on those books, Gregory highlight issues and innovations that are generally overlooked today.

But what intrigued even more about Gregory’s essay is how Liefeld’s work to refresh New Mutants seem to mirror James Tynion IV’s recent work on Batman. Both came onto their books at moments when the titles faced similar commercial and narrative dilemmas; and their solutions likewise have more in common than I would have expected.

At the time Liefeld came onto New Mutants, Gregory notes, the X-line was struggling under the weight of its own continuity. Both Chris Claremont on Uncanny X-Men and New Mutants and Louise Simonson on X-Factor (and later New Mutants) had woven a rich tapestry of character arcs and long-form stories over the course of many years to great commercial success. But in wake of the “Inferno” crossover — which resolved many plotlines, some going back many years — all three books found themselves narratively adrift and losing readers. “After 14 years of Claremont,” writes Gregory, “the entire X-line had become a mess of continuity, and the barrier for new readers was the highest ever.”

Liefeld arrived on New Mutants as penciler with issue #86; one issue later he and Simonson introduced Cable to the X-Men universe. And Gregory argues that while Simonson and editor Bob Harras were certainly partners in the creation of that character – something Liefeld disputes – the introduction of Cable would capture much of what Liefeld would bring to the X-universe: First, the character was new, 1 and with no backstory readers would simply have to read the book to understand who he was.

In Liefeld’s relatively short run on New Mutants/X-Force, he and his co-writers would introduce many new characters – an astonishing 17 just in his 15 issues of New Mutants – and another seven in the 12 issues of X-Force he co-scripted with Fabian Nicieza. And while many of those characters are forgettable, 2 others really did become franchise players in the X-verse, 3 characters that have offered fresh doorways into all things X.

Second, Cable’s appearance almost immediately gave the title a new mission. Within just a few issues of appearing Nathan takes over the New Mutant team and directs them to a completely new purpose, again tearing away the dense web of continuity that had been suffocating the title and allowing readers both new and old a new way into the series. 4

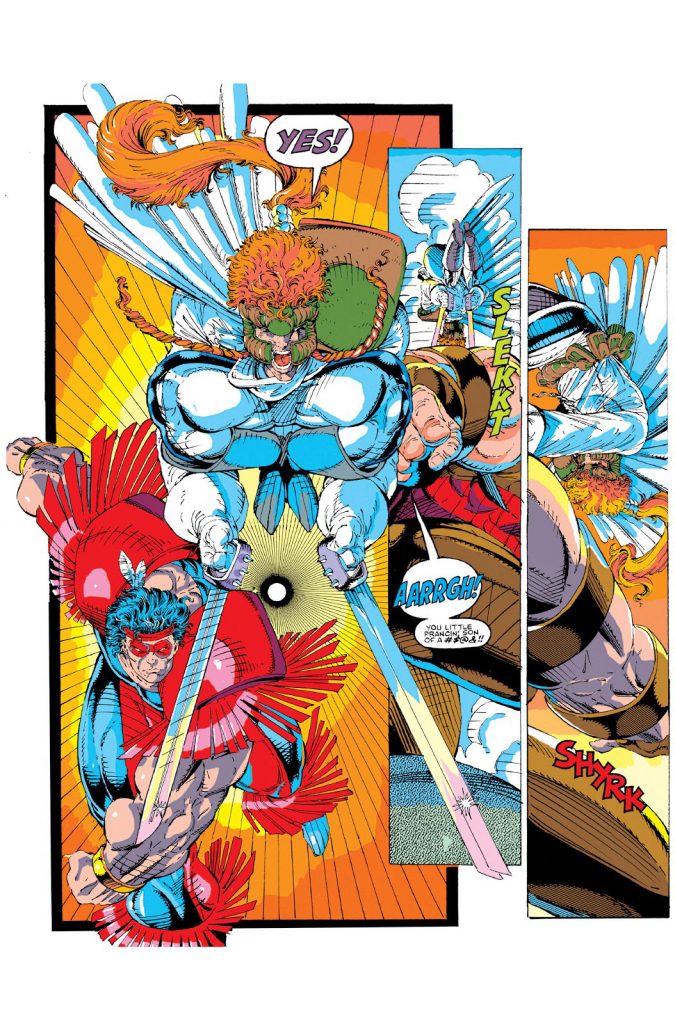

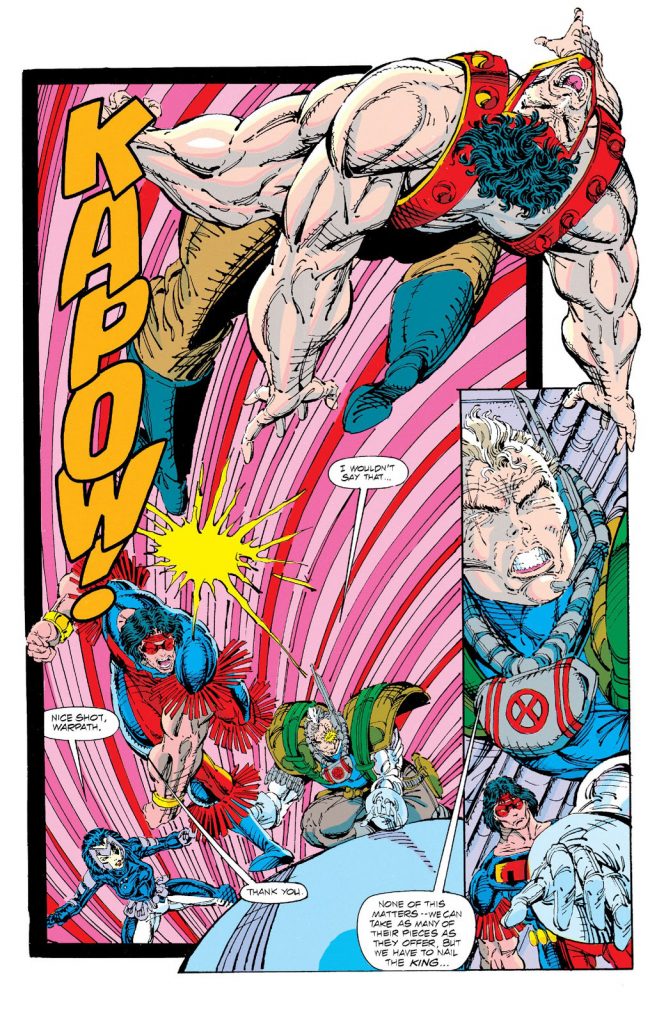

Third, having the Always at the Ready Super-Soldier with Big Gun and Strike Force as its lead allowed New Mutants to quickly shift in emphasis toward semi-constant, big, splashy action. As though trying to blast the book clear of the constant pull of the X-line’s narrative gravity, 5 Liefeld’s art tried to create a constant experience of energy and forward propulsion. Pages often have just a few panels, with characters bursting out of the frames as they fight one another. In Liefeld’s work, says Gregory, “Heroes and villains are not constrained by the limits of the panels. Their action is so outsized it breaks the foundational limits of the page.” 6

Under Liefeld, the New Mutants storyline became fundamentally simple and accessible: the team fights bad guys in order to survive/protect mutants. It was a far cry from Scott falls in love with a woman who looks like the love of his life and then abandons her when the love of his life returns from the dead (again), but it’s okay because she turned out to be a clone 7 anyway. But that was exactly Liefeld’s point; enough with the plot lines that took a dozen years to unfold and a Wikipedia page to understand. Let’s just tell a big, crazy story. And readers surged due to the change. 8

For a while, anyway. Gregory notes the troubles that Liefeld got into when the book rebooted as X-Force. Having worked so hard in New Mutants to move fast and shake things up, X-Force spends a weirdly large amount of time with the team…just kinda hanging out. In issue two, ten pages of a 22-page issue are spent on a training exercise; a few issues later we get another training sequence, and the next issue another again, each of them three or four pages long.

Paradoxically, Liefeld’s greatest strength, his big bombastic art, itself became in many ways his central obstacle: “A subplot that may have taken Claremont a single page, “ writes Gregory, “often takes Liefeld three or four.” Meanwhile new characters 9 just sort of stumble in and instead of actually setting a goal and doing anything the team mostly just reacts to stuff that happens around them.

Having said that, and acknowledging the flaws of Liefeld’s artistic style, 10 Gregory argues convincingly that Liefeld’s fundamental mission was “anti-continuity,” streamlined storytelling that discarded backstory in favor of easily accessible events, hero shots, action. His approach was intended to give people new ways into the X-line, and something straightforward to enjoy. 11

I grew up on Claremont’s Uncanny X-Men, and they meant the world to me. But today I can barely get through an issue’s worth of his narrative boxes and exposition. It’s like driving with the parking brake on. With Liefeld I might be careening off a cliff, or driving fast but heading nowhere. But sometimes you just want to ride a rollercoaster. You want to feel a sense of speed.

For all its history and large cast of characters, Batman as a series has a surprising capacity to overcome the weight of continuity. Readers need to know a few things, sure – Bruce’s parents were killed in front of him; 12 Jason Todd was beaten to death by the Joker; 13 Barbara Gordon was shot and paralyzed by the Joker; Bat loves Cat; and James Gordon is the unsung hero of the story. 14 Clearly, there is an enormous amount more to his story than that; but its value stems more from being a source for writers to draw on rather than material readers have to remember. And as New Life-Changing Events occur, all that past history can actually moderate or undermine their likely significance. Is Alfred really never going to come back? Are we actually stuck with the Batman who Laughs forever? Really?

And yet, in the last ten years the Batman title has found itself building out a lot of continuity.

Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo’s five plus year run on Batman, which was preceded by eleven issues of Snyder’s Detective Comics and would be followed by his Dark Nights: Metal, Batman: Last Knight on Earth, Justice League and now Dark Nights: Death Metal, offer a sort of modular long-form story. Many of the series’ arcs provided chances to jump on board the title, but at the same time a bigger world and story was being build, first in Gotham, then beyond.

When Snyder moved on to expand some of the ideas he had developed in Batman with Dark Nights and Justice League, Tom King took over Batman and built out his own 85+ issue one-continuous-epic of Bats, Cats, Banes and a hearty Hell Yeah. 15

And even as King worked his nine-panel, I Love Characters You Forgot Existed and Also I Live to Break Your Heart magic on the title, at some point readership started to lag. People will point to different reasons: building up the Bat/Cat relationship in such a patient and unexpected way, only to then not go through with the wedding, made readers feel burned; or Bruce’s road back to Gotham after Bane “wins” took too long.

But in some ways the real dilemma of King’s run was that his story offered few if any points of entry after issue one. Basically, for the four year span of his run jumping onto Batman with the latest issue was impossible. You had to start at number one. 16

So James Tynion IV came on the scene last year faced with this situation of a title struggling narratively and to some extent commercially 17 under the weight of these different kinds of continuity – both a long-form love/revenge story and Snyder’s cosmic Bat-mare.

Tynion is no stranger to continuity-rich storytelling, either in his own work or in the Bat-verse. He collaborated with Snyder regularly on Batman, wrote Talon, co-wrote Batman Eternal and Batman and Robin Eternal with Snyder and others, and wrote Detective while Snyder was helming the main title. 18

But in the face of his starting point on the book, Tynion’s storytelling strategy has been similar in some ways to Liefeld’s on New Mutants thirty years earlier. First, he immediately begins to create new characters. Bit players like Gunsmith and Mr. Teeth, just to whet our interest; then “The Villain” in the Designer – who in many ways looks like a character Liefeld could have designed. 19

And while we were meeting these characters Tynion was announcing in his newsletter the coming of other seemingly more significant players — Punchline, who brought speculators to a frenzy almost as soon as Tynion mentioned her; Clownhunter, who Tynion has been talking about for months and seems like a darker take on the Robin idea; and most recently Ghost-Maker. Each of these characters offers someone new for fans to get excited about, a way into the Bat-verse that they can call their own. 20

Unlike Liefeld, whose run on New Mutants had an underlying “And Then There Were None” vibe, as they were getting rid of another main character every couple issues until Sam and Boom Boom are literally standing there wondering how exactly is this still a team book, Tynion builds his initial nine-issue story mostly out of established characters—The Riddler, Catwoman, the Penguin, the Joker and Deathstroke. But with these characters, too, his approach is highly streamlined; to understand his story you don’t need to know anything about any of them that you don’t already know just from existing in the world. Everything important about them is going to come in the course of the story unfolding.

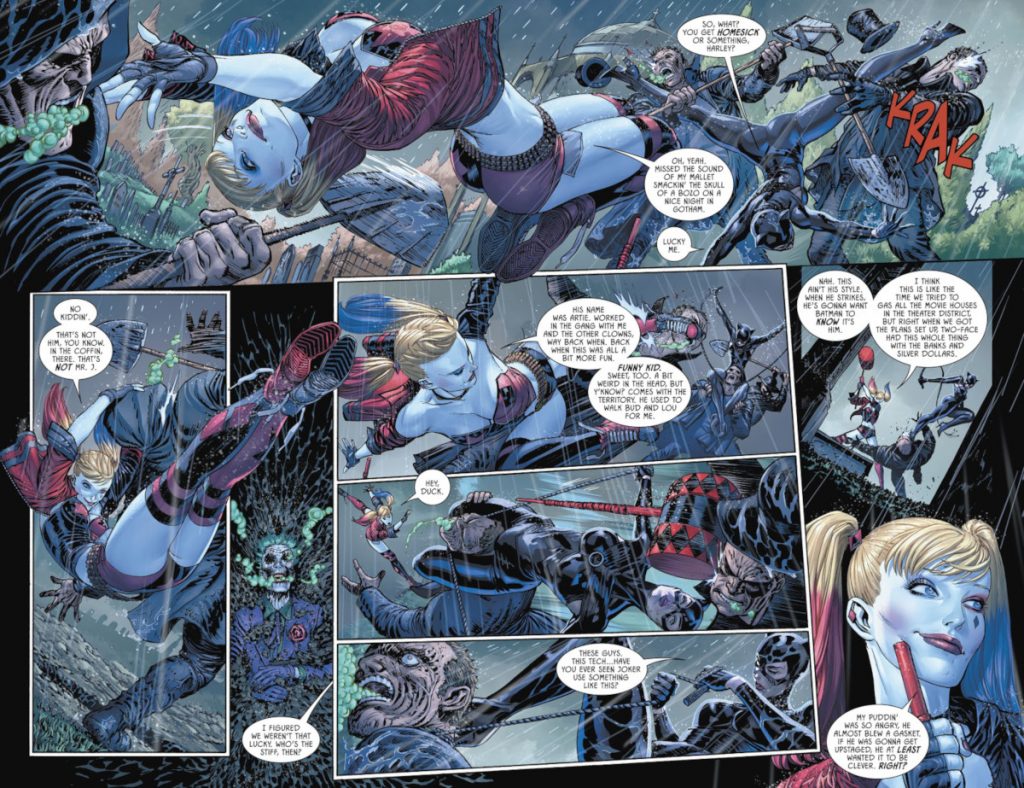

Which leads to the second – and in some ways most important – element of Tynion’s fresh approach. The story hits the ground running in issue #86, with Batman working to take down Deathstroke’s Merry Band of Homicidal Maniacs, and it just never ever lets up. You could be excused for thinking that the entire run so far has been long action chase, fight and flight sequence. Every issue has the feeling of starting literally from the moment the last one ended, and entails a continuation of that same rollercoaster ride filled with bold story choices like letting Cheshire get hit by a truck or Punchline slitting Harley’s throat and big visuals of characters posing dramatically, too big to be contained in a panel, or flying between frames as they fight.

There are any number of times when in fact Batman is not fighting, chasing or being chased. But even in those moments, there remains a sense of constant forward propulsion. Part of that comes from context: so in issue 90 as Catwoman explains what is really going on here, her and the other Rogues’ long-ago first encounter with the Designer, even though what she’s doing is essentially exposition, because it’s taking place in the midst of such urgency and danger in Batman’s life, it feels essential rather than a distraction.

It’s interesting to note the degree to which Tynion’s approach here stands in contrast with Liefeld’s work on this point. Even as X-Force provides almost constant action, any time the book needs to offer exposition — and the book has A LOT of story to tell 21 — the book suddenly comes to a screeching halt.

The Catwoman sequence and others like it also keep the momentum going so well because they’re couched in action. As Catwoman begins her tale, artist Jorge Jimenez has her running across the rooftops of Gotham. There’s actually no story reason for this; she’s just going to meet up with the other rogues. But her movement provides that ongoing sense of momentum. Likewise in issue 95 we begin in a flashback to Batman’s early days of dealing with the Joker. And while the content is Bruce and Alfred mulling over what the Joker might represent, what his endgame might be, Jimenez has Batman roaring through Gotham City in the Batmobile.

Tynion’s story hasn’t offered a whole new mission for Batman or the series, another contrast between his approach and that of Liefeld (although at the end of “His Dark Designs” he does suggest the journey of the series might be toward some new take on the Dark Knight. 22 One of the challenges the book has as it heads into its second major arc, “Joker War,” is how it will come to distinguish itself from the chaos Bane only recently inflicted. So far the answer seems to be that rather than another hostile takeover, the Joker represents an existential threat. He is the Day After Tomorrow polar vortex of super villains, a catastrophe you can’t stop, you just have to wait out. His takeover is different because the prospect of it is so goddamn terrifying.

After so many years of world building and long emotional arcs, Tynion’s choice to go for something a lot more accessible and bombastic feels transgressive and exciting. It’s not terribly clear what it will all amount to in the end, or what the book is really “about”; but that doesn’t seem to matter to readers. After years of Batman: The Character Drama and Batman: The Nightmare Horror Series, 23 Batman: The Action Movie is a relief and a giddy rush.

The popularity of Tynion’s run absolutely precedes the pandemic. And yet, I was struck in David’s recent conversation with retailers by comments on what seems to be selling best in this crazy nightmare year: the familiar.

“People want the tried and true titles,” said Patrick Brower of Challengers Comics + Conversation. “Buyers just aren’t taking as many risks right now.” 24

Some of that might be the fact that comic sales right now are missing a key element: the ability to browse. Seeing a title on the shelf or paging through it in your hands can go a long way toward buying it. It’s also true that everything around us every day seems new right now, and not in a good way. In such a context, maybe the prospect of new books filled with unfamiliar characters is just not as attractive. 25

Considering that, I wonder if a Liefeld-reboot of New Mutants would still have been successful in the kind of situation in which we currently find ourselves. 26 His run certainly represented a massive change in the storytelling of New Mutants in particular and the X-books in general.

And yet in another way it was not radically new at all. Every weekend teens were going in droves to watch action movies that looked just like this, each of which made about the same amount of sense. 27 We all reference Ellis and Hitch as the ones who brought the widescreen aesthetic to comics storytelling. But ten years earlier Liefeld — and Jim Lee, Todd McFarlane and others — had already given comics that Schwarzenegger summer tentpole action movie feel.

In a sense maybe that’s what made Liefeld’s run so compelling. He took the dense and moody and made it insanely big, intensely violent and very familiar.

Tynion’s Batman run itself offers an unexpected comment about all this. In the most recent issue, #95, the movie theatre owner wonders what the Joker could possibly be looking for in his reels of old movies. “Folks don’t want to see something they’ve seen a hundred times before,” he says.

“They always say that,” the Joker replies. “But they never mean it. They want all the pieces in the right places. All the characters saying the parts they want them to say.

“Which isn’t to say they don’t want something new. They want to see it peeled back, to find out there was a layer underneath all this time they didn’t know about.”

That sounds quite likely to be Tynion’s take on writing Batman. But maybe it’s also the most that many of us want to handle right now: all the characters in their familiar places, playing their selfsame roles, seen at best from a slightly different angle (and honestly, maybe we don’t even need that). There’s room in the world of comics for sustained, 85+ issue epics or even 16-year-long runs; 28 but sometimes, we just need a comic that’s trying to have fun telling superhero stories.

Or at least seemed that way; yowza did that change.↩

Was I the only one that got excited to see New Mutants #11 recently do something interesting with Wildside? Can a Thelma & Louise-inspired Tempo & Thumbalina road story be far behind???↩

Including Deadpool, Domino, Shatterstar and, of course, Cable.↩

Gregory also notes that while Liefeld’s work on the X-line gets criticized today for being superficial and simplistic, in fact he was trying to steer New Mutants back to its central conceit, “that of the struggle of an oppressed class of people.” What had harmed the book was not just continuity but metaphor-drift.↩

Which I propose measuring in units of Claremont.↩

They’re also often close to bursting out of themselves, their body proportions and gun sizes exceeding any possible reality. Everyone in X-Force has so much muscle mass I get exhausted just considering how tiring it would be to move under all that weight. *shakes head, grabs another Chips Ahoy*↩

…ish?↩

It does feel crazy to describe any story involving Cable as “simple” or “streamlined.” But in New Mutants, he really was.↩

Like Siryn and Kane.↩

Specifically the hyper-physicalization of his characters.↩

It is a great irony really that this artist who made his mark by brushing aside dense contextualization for the immediacy of story today requires at least as much contextualization himself to be appreciated.↩

Cue pearls falling in slow motion…↩

…and comic book readers of the time.↩

Team Gordon, always.↩

Someone get Kite Man his own title, please and thank you.↩

Having said that, I personally loved the run. And I find a lot of the later issues, even as they extended the story beyond what was necessary or maybe prudent, are also some of my favorite stand-alone issues. King knows how to do cool stuff with 22 pages/198 panels.↩

At least relative to its historic dominance.↩

I live in waiting for Tynion and Detective/Justice League Dark collaborator artist Alvaro Martinez Bueno to create a title of their own together. The two tell a great story.↩

Fur. Jewelry. Enlarged Weapons.↩

I’d like to include the Designer in this cohort as well; I think his “exponential leap forward” thinking makes for a great Batman villain. So far his prospects as a long-term character in the Batverse seem um, less than promising. But you never know.↩

An only partial list of things referenced in the first 12 issues: Cable and Stryfe are clones of each other; Cable was part of a group of mercenaries who did secret stuff; Cable is Jean and Scott’s abducted son; Sam Guthrie is an immortal; There are immortals; Jonathan Hickman will some day make sense of them.↩

Now with glow in the dark armor!↩

It’s hard to boil Snyder’s run down, but Batman facing his worst fears brought to life is certainly a big part of it.↩

Some notable exceptions were mentioned by other retailers, though, including books by people of color seeing gains in some shops.↩

One thing I’ve noticed in my own life is that where I used to listen to a ton of podcasts, I haven’t listened to a single hour of anything in almost five months. I just don’t want any more input right now, thank you.↩

*imagines pandemic in 1990 without internet, begins shrieking, consumes world’s supply of Chips Ahoy*↩

Among the most popular movies of 1990, the year Liefeld drew New Mutants: Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles; Total Recall; Die Hard II; Days of Thunder.↩

Okay, maybe not a 16-year run in 2020, but four or five years anyway.↩