Anyone Can Wear the Mask

A look at “real people in superhero universe” stories and how they twist the classic wish fulfillment fantasy.

Wouldn’t it be awesome being a superhero?

Being super strong, maybe invulnerable too. Having powers far beyond those of normal men. For most of us, it’d be a dream come true. Sure, there’d probably be hardships too. With great power comes great responsibility, and all that. A price to be paid. But it’d be worth it to fly through the skies, right?

Superhero comics are the ultimate wish fulfillment stories. Despite all the tragedy, it’s almost impossible not to – on some level – go; “I wish that was me…I wish I could do that!” Having your entire planet blown up would be awful, yes. But being faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive and able to leap tall buildings in a single bound still sounds pretty awesome.

After all, everyone dreams of being Superman.

And no one dreams of being Harvey Bullock. 14

Having to do police work in a city with criminals like The Joker, Catwoman and Penguin can’t be fun. Following a trail on some stolen diamonds, only to find out that they were stolen by Mr. Freeze and then suddenly you’re supposed to arrest a superhuman guy in a mechanical suit that has a freeze gun? Plus, your gun’s bullets bounce off him and backup is still five blocks away? A lot of us have dreamt of being cops, but being a cop in Gotham? No, thanks.

This doesn’t mean that ordinary people can’t be heroes too, even when compared to Superman. These stories of real people in superhero universes 15 provide an interesting twist or wrinkle on the classic kind of wish fulfillment angle that most superhero comics have. While not a huge subgenre, there has been a large number of series published over the years, mostly starting with Marvels by Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross.

This wasn’t the first comic to deal with the subject, as series like Damage Control 16 and single issues such as The Amazing Spider-Man #248’s “The Kid who Collects Spider-Man” 17 had already explored the subject to varying degrees. But Marvels did it to a more significant extent, which is most likely why it had such an impact and inspired so many other titles. Researching this piece, I was struck by just how many of these series are painted, for instance, a clear trend that Marvels started.

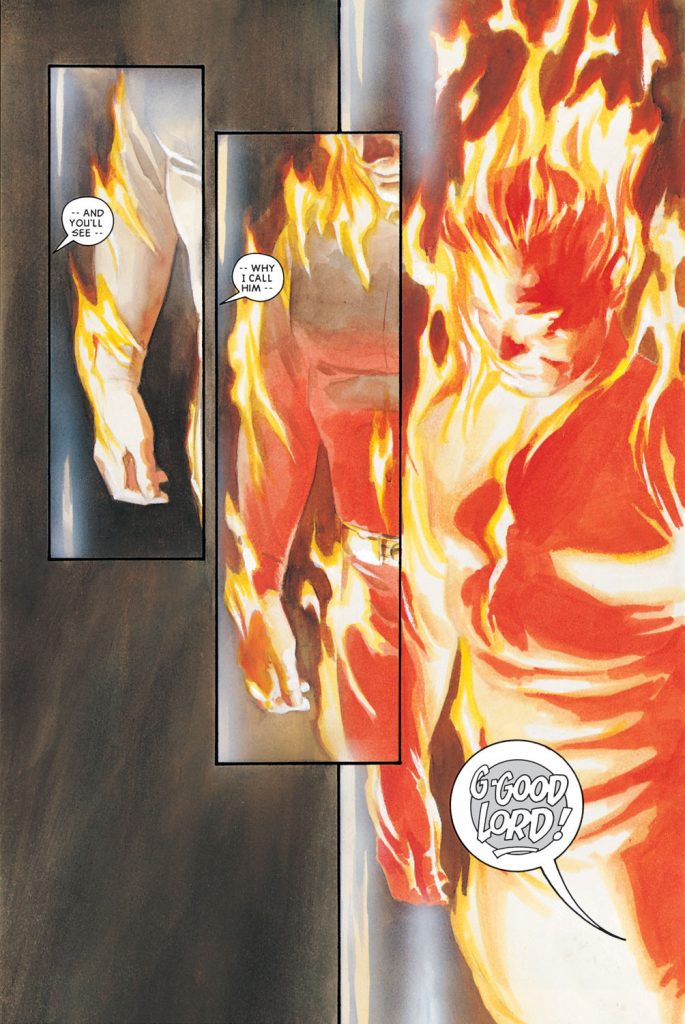

Marvels opens with a group of journalists, ordinary people like you and me, sitting around talking about what’s going on in the world before heading to a science exhibition. Ross paints this opening scene in subdued colors, greys and dull browns, both grounding the world right from the outset but also making the reveal of the original Human Torch’s bright flames stand out even more. This helps reinforce the feeling of something new and colorful entering the world. It’s not part of our world, unlike the people in the opening scene.

This is mostly how the superhumans are depicted in Marvels. They’re other, removed from the reader, often in the background, shown in flashbacks or on TV screens and news clippings. They’re not something that Phil Sheldon 18 really interacts with directly, even as he’s affected by their actions.

Instead, the focus is on what those actions mean for the world. How seeing someone like the Human Torch flying through the sky or Namor fighting whole platoons of Nazi soldiers makes Phil feel like less of a man, unworthy of his fiancee. Marvels shows how superhumans warp the world around them, changing things big and small, from dances being interrupted by their fights to their role in World War II. For most of the first issue, Phil is unable to decide whether the superhumans are a good thing or not, but it ends on an optimistic note, with all the heroes diving in to fight the Nazis and Phil there to chronicle it all.

Things become more muddied in the second issue as mutants are introduced. The public, including Phil, cheers on the Avengers and the Fantastic Four but clamors for the blood of mutants, fearing them and what they represent. Busiek and Ross show, in a more direct way than ever before, the sheer amount of hatred mutants are faced with. We’ve seen the X-Men fighting against Sentinels and other anti-mutant threats many times before, but these just seem like extremists. Not everyone feels that way, surely.

Marvels shows otherwise. It shows huge crowds of people hounding mutants, throwing bricks at them, literally chasing them with pitchforks. And crucially, our protagonist Phil Sheldon does this as well, and Phil is the guy we’ve come to know and care for, someone we understand, someone we think knows better. If he can get swept up in the rage and hate, then it’s clear how powerful and prevalent the hatred is.

Eventually Phil realizes the error of his actions and is horrified by how he acted, which further informs his view on superheroes. He can’t singlehandedly defeat platoons of Nazis or travel to other galaxies to fight in an intergalactic war, but that doesn’t mean he can’t learn from their example and go out and do good. As public opinion rapidly shifts against and for them, Phil is standfast in his belief in them and the good they do, even doing what he can to aid their public image in the occasion they’re wronged.

But the story ends with him having become jaded to the whole thing, unable to see the wonder in superheroes anymore, passing the torch of telling their story to his assistant, because for her everything is still new and interesting.

This, in many ways, is the same thing that Marvels does. It shows us a new side to these heroes and villains that we all know so well. The fact that a man can fly through the sky, throw cars around or stick to walls isn’t amazing to us anymore. But reading Marvels, it becomes amazing again, because we’re not seeing the world through Spidey’s eyes, we’re seeing it from the perspective of someone ordinary.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

Including, I reckon, Harvey Bullock. ↩

As opposed to superheroes in the real world, à la Watchmen, Brilliant or MPH, just to name a few.↩

A series mostly focused on the humorous aspects of having to clean up and rebuild after superhero fights.↩

A back-up story about, you guessed it, a kid who collects Spider-Man memorabilia meeting Spider-Man, who then recounts his origin to the kid, before it’s revealed at the end that the kid’s in a cancer ward. It’s a very clear example of superhero comics being wish fulfillment and the power that that has.↩

The main character and our audience surrogate to the Marvel universe.↩

Such as a dispatch operator for the Honor Guard or a man who lost his wife in a reality changing crisis now helping others, to name just two examples.↩

Well, for the most part. But that’s a topic for a very different, more political kind of site.↩

And then falls.↩

And the relaunches that followed it, Mary Jane: Homecoming and Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane.↩

Something that’s also very much brought to the fore in the recent The Amazing Mary Jane series.↩

And, as mentioned, other Astro City stories show that ordinary people can save the world with their actions too.↩

Like the Powers police division are.↩

Such as her relationship with Harry Osborn, born more out of liking him as a friend than being in love with him.↩

Including, I reckon, Harvey Bullock. ↩

As opposed to superheroes in the real world, à la Watchmen, Brilliant or MPH, just to name a few.↩

A series mostly focused on the humorous aspects of having to clean up and rebuild after superhero fights.↩

A back-up story that tells the story of, you guessed it, a kid who collects Spider-Man memorabilia meeting Spider-Man, who then recounts his origin to the kid who, at the end, is revealed to be in a cancer ward. It’s a very clear example of superhero comics being wish fulfillment and the power that that has.↩

The main character and our audience surrogate to the Marvel universe.↩