The American Dream: How Telling Your Own Stories Became the Endgame for Comic Creators

Do you remember reading comics as a kid? How you’d read a comic – maybe it was an X-Men title or a Batman one – and afterwards, you’d go and either draw your own comics or think about what you would do if you were telling those stories? You weren’t alone. I was right there with you. So were many others.

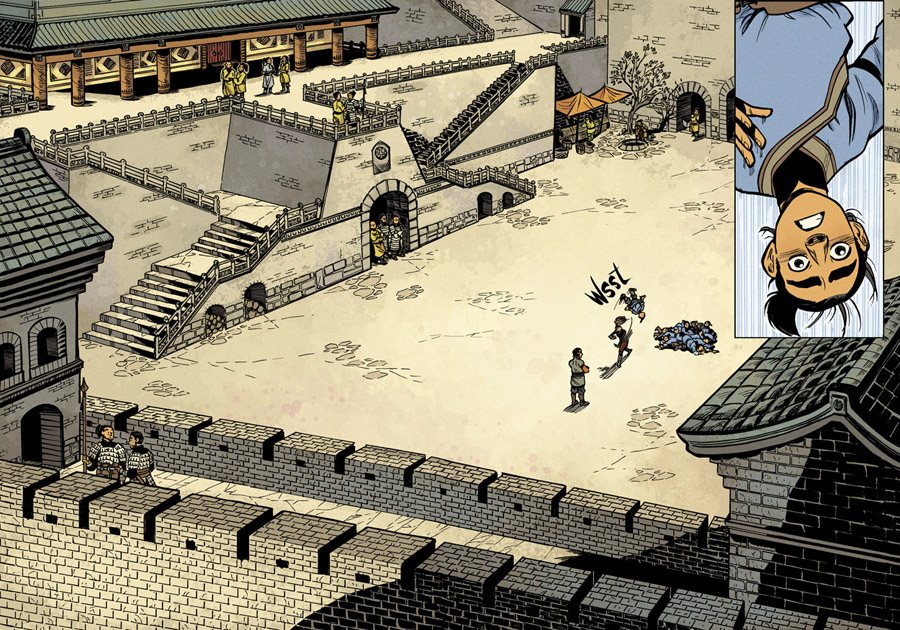

“I had two goals, really,” Kurt Busiek, the writer of The Autumnlands and Astro City, said when asked about what he aspired to early on. “On the one hand, I wanted to write X-Men someday and fix everything I thought was wrong with it. On the other, I wanted to write Iron Man and bring forth all the potential I saw in it.”

“Early on, when I was 12 or so, it would have been to draw my favorite superhero comics, like Uncanny X-Men or Fantastic Four. When I was 20, it would have been to draw my own superhero comics,” shared Cliff Chiang, artist of the upcoming Paper Girls with Brian K. Vaughan.

As comic readers age, many branch off and never get the chance to tell that perfect superhero story like they always envisioned. But for creators like Busiek and Chiang, they get the chance to tell stories perhaps not exactly like they pictured, but in the ballpark. That’s cool. While Busiek was never able to fix the X-Men – which worked out, as he had lost interest in them over time – he did get to work on Iron Man. He admitted it was a fun experience, but not what he had always dreamt of thanks to internal pressures shifting what he was planning. But over time, an important thing happened: his aspirations changed.

“I also got new dreams, of doing my own stuff, of building worlds rather than playing in other people’s worlds,” Busiek said. “And that’s been a lot of fun too.”

In recent years, comic book dreams have been shifting for creators – not just Busiek – including writers and artists both fresh to comics and those in the industry for years. While many still aspire to write Spider-Man or draw Superman, more and more creators are imagining what it’s like to tell their own stories. To dig into their own worlds. To create their own characters. That’s an exciting change, and one that rings a bell if you think about it.

It sounds like the manifesto Robert Kirkman shared upon leaving Marvel to focus on his creator-owned work. Within that, Kirkman spoke about the shifting paradigm in the comic industry and how creators should stop looking at Marvel and DC as the endgame. Rather, they should be where you build your name so you can better sell your own work – the work you’re more excited about – down the line. At the time, the response ranged from excitement to downright derision. Today?

It sounds like Wednesday.

The Way Things Were and the Way Things Are

“When I started out, if you wanted to do creator-owned comics, you had Eclipse, Epic and self-publishing, and you weren’t going to make much money,” said Busiek. “Marvel and DC books sold so much better than indie books that if you wanted to make a good living and attract a large audience, Marvel and DC were where you went.”

While Busiek’s career started a fair bit earlier than others I spoke to, what he’s describing has been the case in comics more or less since their inception. The industry has changed, but even in 2015 Marvel and DC are the surest shot to get your name out there and to make good money. They offer stability. For comic creators who are sometimes holding down a second job or struggling to make ends meet, that’s huge.

Take Faith Erin Hicks, for example. Hicks is a well known comic creator. She’s won an Eisner Award and has found a lot of success telling her own stories in comics. But earlier on in her career when she was already doing what she’s doing now – writing and drawing her own graphic novels – she would have jumped on an offer of a for-hire job.

“If I had been offered work for-hire gigs back when I first started getting published (2007), I definitely would have taken them. Work for hire pays well, and I was very poor back then.”

That’s the real reason Marvel and DC have always been the endgame for creators. While in our youth we aspire to tell the stories of certain characters, the promise of stability and earnings carries much more weight for the working writer or artist.

“All I wanted was to make a living wage doing some kind of creative work,” Hicks said. “That’s it, really.”

Many creators are like her. Jake Wyatt, the cartoonist behind the webcomic Necropolis, shared that for him, “the end game always was and still is to eventually live off of ‘my’ work.” That’s why most jump at a chance to take higher paying for-hire work. But because of how creator-owned has become more viable financially, it’s allowed for a shift to take place. Creators like Wyatt can focus on their own projects rather than taking more for-hire jobs like he had with Edge of Spider-Verse and Ms. Marvel.

“A book at Image can sell numbers that would get you cancelled at Marvel or DC and the creators can still be making more than they would from a mid-level Marvel or DC page rate,” said Wyatt. “And if the series you penned or drew goes to TV or film, you keep that money.”

“(This) has created (a) weird cycle wherein creators start doing indie books that don’t make money. But they often get Marvel and DC’s attention. Then these creators work at Marvel and/or DC for a little while and garner an audience,” Wyatt added. “Then, if they’re successful, they can jump back over to Image and do their own work for a comfortable income.”

That’s the central idea of Kirkman’s manifesto, and it’s something both newer creators like Wyatt and veterans like The Private Eye’s Marcos Martin are seeing come true before their very eyes.

“There has been a shift where before you’d start your own comic book in order to get into Fantastic Four or Batman,” said Martin. “But now you want to get into Fantastic Four or Batman in order to gain a greater amount of readers and become more well known so you can release your own comic and make a living out of it. A really good living, better than Marvel or DC.”

For most creators, that means what Wyatt said: releasing their own stories at Image. But for Martin – who admits his path isn’t recommended for everyone – it means going a different route. After years of working for Marvel and DC, Martin – alongside writer Brian K. Vaughan – created a digital first publisher called Panel Syndicate to release their own work. Martin, Vaughan and colorist Muntsa Vicente put together The Private Eye and published the comic for purchase at whatever price readers decide. Sounds risky, for sure. Their fate was entirely in the hands of readers. But enough people paid that each of them were making higher page rates with this method than they did at Marvel or DC, according to Vaughan in the back of the seventh issue. That couldn’t have happened ten years ago.

“At some point, you realize you have to make that step to try and do your own stuff and see what happens,” Martin said. “It doesn’t have to be as radical as what I did (laughs). No need to break away from the whole industry and try to change the whole economic model of the world, but I think most artists, writers and creators in general will usually reach that point where you want to try and do something for yourself. I guess you feel you deserve more for all of the work you put into the page, especially if you’re creating new characters. It reaches the point where you feel it doesn’t compensate and you just want to try and find something else.”

“That’s where you make that step.”

That’s not to say money is the sole factor. It isn’t by any means. Chiang’s goals evolved past traditional superhero comics as he aged, and now, what he’s looking for is simple: freedom.

“It probably wasn’t until a few years ago that I realized my true end goal was creative freedom – to be able to choose my projects without worrying about monetary or political considerations,” he said. “I’ve been happiest when I can just work on something that I love and believe in.”

If this all sounds logical and like something that should have existed well before Kirkman’s manifesto, you’re right. In fact, it did to a degree, as Image Comics publisher Eric Stephenson pointed out a couple months back.

“That’s the way it was in the ‘80s when creator ownership first became a thing,” he said. “The vanguard of creator-owned comics was not made up of writers and artists trying to break into comics, they were the biggest names in the business, moving up to the next level.”

“Someone like Frank Miller – he worked at DC and Marvel and established himself as one of the industry’s brightest talents, and then he did Ronin. Howard Chaykin did American Flagg! after putting in years at other publishers,” he added. “Doing books that they had a personal and financial stake in was a step forward, it was progress.”

For many of today’s younger and aspiring comic creators, telling your own stories has become the point they aspire to. It’s thanks to not just people like Kirkman, but also veterans like Miller and Chaykin.

“I think that’s been going on for years now, and the current new generation of creators is already coming in thinking that way. The doors opened in the 80s, they got blasted wide open in the 90s, and now it’s 2015,” Busiek said. “That’s a lot of years for generations of creators to look at books like American Flagg and Nexus or Savage Dragon and Hellboy or Y the Last Man and Fables or Love & Rockets and A Distant Soil and Flight and ZOT! and hundreds upon hundreds of titles, and think, ‘I want to do that,’ rather than ‘I want to draw Wolverine.’”

“It’s been happening for decades, but it’s been building up steam for the last thirty years. Those generations are all around us, getting more numerous every year.”

The biggest difference between Miller and Chaykin’s heyday and now is simple: you don’t have to be one of the biggest names in comics to make a living this way anymore. As Chiang shared, “for an established creator, doing your own book is no longer the risk it once was,” and that gives creator-owned a higher financial ceiling and floor than ever. It’s easy to see why this is becoming the way things are.

The Plusses and Minuses of the New World Order

“The industry’s changed,” shared Busiek. “You’re not facing a choice between making a good living and following your artistic muse. You can do both at once, rather than one or the other.”

That is the crux of why creators are focusing on telling their own stories. Before it was an either/or proposition. Do I follow my heart or do I make enough money to live a little more comfortably? Now you can do both. The allure of that is too great for many creators.

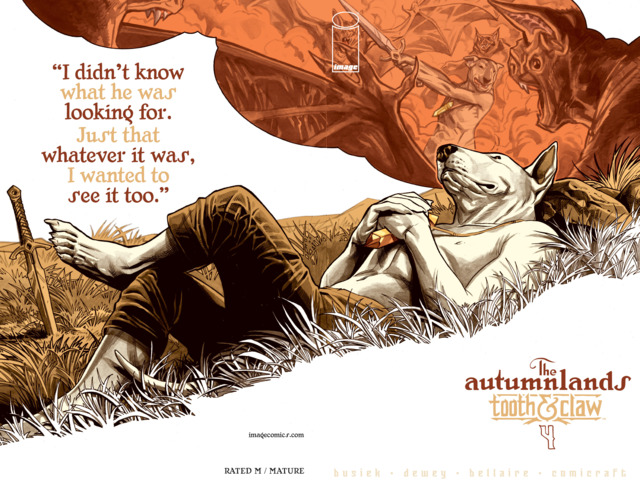

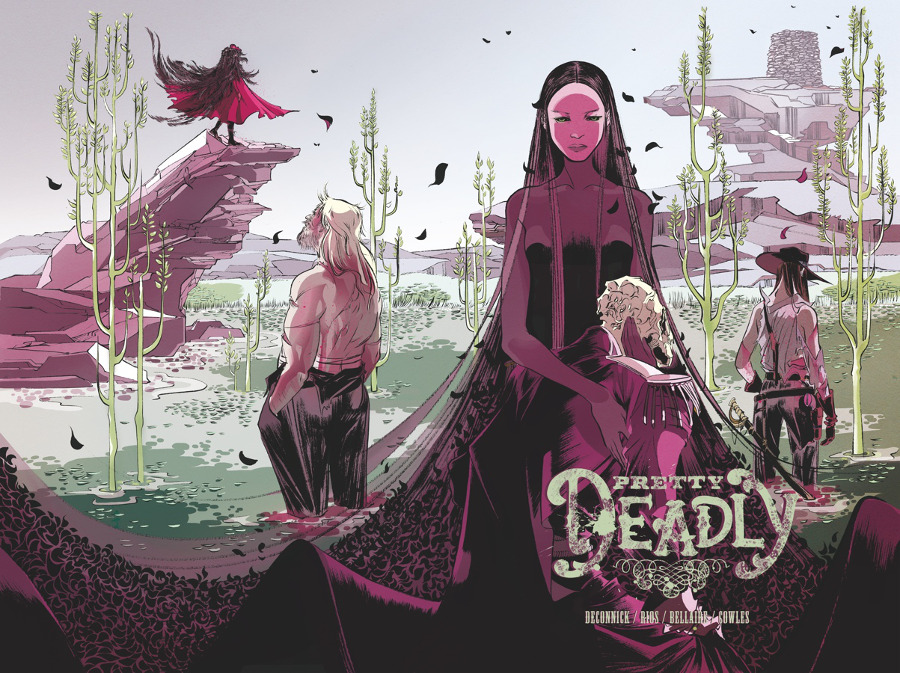

But it’s even more than that. The attraction to telling your own stories is as complicated as the industry itself. For Pretty Deadly’s Emma Rios, a big part for her is having stakes in her own work.

“I think it is truly important to have property over the stuff you do,” Rios said. “That’s what really matters to me when it comes to creator-owned comics – to own it.”

For creators like her, ownership is a complex thing. Its value is multi-faceted, and it means different things for different people. One major part of that is something that was already mentioned.

“Also, freedom, of course,” Rios said. “Organizing your timing, doing what you want with the stories, being able to kill your characters when you want…that’s the best of life.”

For Busiek, it means ensuring simple things that often don’t happen, like keeping his books in print or making sure the stories he wants to tell come to be. It comes down to control.

“You get to build it all yourself, exactly how you want it (or as close as you can manage),” he said. “That’s another advantage of control — I don’t have a boss telling me to change someone’s costume to something they like better, or putting a new logo on the book I don’t like, or having standardized lettering that doesn’t fit the art — when I’m doing books I create and own with my collaborators, it’s just us.”

“Stand or fall, it’s our book, done our way, looking the way we want it to,” he added. “That’s a huge thrill.”

For some, that level of ownership – the fate of the book relying on you in full – could be paralyzing. But for Hicks, she looks at it in a similar way to Busiek.

“For me, when I make a creator owned comic, something that I created from the ground up, all of it is me,” she said. “I’m not working with someone else’s characters or beholden to someone else’s canon, I’m the god of my own world. And every hour I put into that comic is my hour. I’m investing in my creativity.”

“That sounds super bombastic, but that’s how I feel sometimes. It’s like, this comic is all mine, for good or ill,” she added. “If it’s great and people love it, that’s for me. If it’s terrible, that’s on me.”

While Wyatt’s committed to telling his own stories – he’s doing it in a big way with how he’s developing Necropolis – he sees downsides to this model that others didn’t mention. While getting to do what he wants is a big thing for him, it can lead to struggles for others.

“The Internet has no editorial guidelines, and Image Comics’ editorial hand is almost imperceptibly light,” he said. “This, of course, is a double-edged sword—no one is there to help you tell (or market or find collaborators for) your story.”

“But nobody’s stopping you, either.”

The financial side looms large for all the creators I spoke to. And it should. If Marvel and DC have held onto their dominance thanks in part to their promise of consistent, larger paychecks; then creator-owned comics have taken a greater grip because of a much more glittery proposition: their upside.

Cartoonist Natalie Nourigat once described creator-owned properties as “lottery tickets,” and with the potential for deals like the one Robert Kirkman signed with AMC or the duo of Kelly Sue DeConnick and Matt Fraction struck with Universal, it’s easy to see why. Peak earnings for a creator-owned property dwarfs what for-hire is capable of. Not only that, but they’re more stable than they ever have been before. So if both options provide stable incomes for creator X, who wouldn’t choose the one with creative freedom and higher potential returns on its side?

“We seem to finally be in a place where it can be profitable to make your own comics outside of the Big Two. My career has flourished through publishing with the graphic novel imprint of a book publisher,” Hicks said. “Other writers and artists find their niche at Image. And we can actually make a living writing and drawing our books.”

It’s changed enough that for top creators, Martin said staying with Marvel or DC can be a riskier proposition than releasing their own work, financially speaking.

“Most people realize now that you can actually make a better living working outside Marvel and DC than you can working at Marvel and DC. Marvel and DC might be better in the short term because of the guaranteed money, but it can be actually riskier than trying an independent or working with your own creations,” Martin said. “In Spanish, we have a saying, ‘bread for today, hunger for tomorrow.’ That’s what could happen at Marvel and DC.”

To paraphrase Hicks, going the creator-owned route is investing in yourself, and that’s what Martin is referencing. You work at Marvel or DC until you don’t, and then what? But if you release your own work, the financial success could have a longer tail. Especially if you’ve already made a name for yourself.

And with options like Patreon, Kickstarter and digital comics available to writers and artists, reaching large audiences is easier than ever. That was one of the most appealing things to Martin. Panel Syndicate offered ultimate freedom that no publisher could ever match. They could forge closer relationships with readers in new ways while providing them an affordable option that avoided all the pesky things he didn’t enjoy about the old way of doing things (“the whole printing process to me…it’s hard for me to go back and think of that now”).

“Freedom and Money,” Wyatt said. “The American Dream.”

Again, though, it’s not all roses. As with any lottery ticket, you could make it big, but there’s a better than zero chance you’ll make very little. Even though this creator-owned shift has raised the financial floor for creators while also giving them higher potential earnings, Wyatt cautions there are still struggles.

“It’s made it a lot easier to make things, but not much easier to actually live off of making things. All these other avenues – Kickstarter, Patreon, zine imprints, web media – have made it absurdly simple and easy to get your work out there, and even to get a little money for it,” Wyatt said.

“But earning a living wage from your work is harder, and not just for people working in new platforms and media,” he said. “The starting rate for comic artists at most publishers has been steadily dropping. I made less starting out than my older friends did, and people coming to the table now are starting lower than I did.”

“And that’s inside the establishment.”

Wyatt is developing Necropolis slowly, but it’s for a reason. He has a full-time job as a director in animation and advertising. He needs that job to make a living, and he’s not the only one.

“There are people out there winning Eisners and moving serious numbers and bagging groceries part-time because they signed contracts with predatory publishers,” Wyatt added.

“(It’s) easier to make your work and make a little money off of it. Maybe universally harder to ‘make it.’ To live off your work. Less money on the table all around, and plenty of publishers taking advantage of that fact.”

There are other downsides beyond what Wyatt mentioned. With veteran creators putting greater focus on telling their own stories, smaller publishing houses have less incentive to publish newer creators as long as they have bigger names knocking at their door. It makes the first step of comics different than it was before. New creators have to look elsewhere to get their name out at times. Options such as webcomics, digital books through programs like ComiXology Submit, or self-published comics (as Michel Fiffe did with Copra) are there for those who can’t garner the attention of publishers.

Beyond that, expanding the publishing side of comics has increased the breadth of what’s released. That means more comics with the same amount of space and buying power at comic shops, which can make it difficult for shops to justify ordering books from newcomers or even comics from veteran creators. With retailers being the true customers for comic creators trying to earn a living from their work, that can be the thing that makes or breaks their passion project.

But with any action comes an equal and opposite reaction. These things are expected in times of great change in any industry. As with others, time will cure a lot of ills, and when everything shakes out things will probably look different. That’s not necessarily a bad thing.

“Nothing’s as big as it used to be; the audience is becoming decentralized, ebbing out into new niches every day,” Wyatt said. “I have no idea what the comics landscape will look like ten or twenty years from now.”

“Which is, to me, exciting.”

A Better Future

One thing every creator I spoke to was asked was this: what do these changes mean for the future of comics? Will the idea that kids are growing up reading comics by Raina Telgemeier and Kazu Kibuishi and then following it up with books like Lumberjanes or Saga change what comics look like? Will today’s creators succeeding by telling their own stories empower the writers and artists of tomorrow? Most weren’t certain, or at least didn’t want to speak for others. But some had thoughts, and they were all on the hopeful side.

“I really hope so, because it’s the only way forward,” Chiang said. “As much as I love the superhero comics I read as a kid, I wouldn’t want those to be the only books available today. There is so much growth potential in comics as long as we can show the world great stories in every genre. The work—and the medium—will speak for itself.”

“I encourage them to tell their own stories,” I Hate Fairyland’s Skottie Young said regarding young creators starting out. “Not because one is better than the other, or you’ll be judged for one or the other, but because nowadays it’s the best way to get to whatever end goal you (are) looking for. If you want to make up your own books, do it. Put it out. Boom. You’re done. Do that again and again. If you want to work for Marvel or DC, make your own books. That’s one of the best ways to get noticed today.”

“Make your mark with your ideas and your work, even if your end goal is to land on Spider-Man,” he added. “Who knows, your story could be the next Bone and you wouldn’t need to work for anyone ever again.”

Hicks is excited about all of the options both readers and creators have today, and thinks they bode well for the future of the medium – especially compared to where things were when she was younger.

“I remember being desperate to read comics when I was a teenager and there was nothing for me. Like, just nothing,” she said. “Now there are dozens of comics that I would’ve loved to read when I was 15, and more importantly, they’re pretty easy to find. Comics are carried in bookstores now, they’re in libraries, they’re in schools. Comics will always have an access problem, I think, but it’s gotten a lot better. Kids will be able to find the kind of comics they want to read, and maybe they’ll keep reading and fall in love with the art form and want to make their own comics.”

“I’m really excited to see what comics will become in the next twenty years. I hope that we’ll continue to see a blossoming of diversity of voices in comics. I think we will,” she added. “The future of comics seems really bright at this moment in time.”

“Selfishly, I hope it will include a spot for me.”

For Rios, telling her own stories isn’t just something she does. It’s something she needs. That makes having options like her collaboration with Brandon Graham on Island magazine invaluable. Again, that’s something that would have been hard to imagine even ten years ago.

“Brandon and I talk about this a lot. This is a moment in our careers in which we basically can do whatever we want and be published,” she said. “That’s a dream come true.”

Rios added that this freedom adds pressure to her creatively – “you have to push yourself to try different stuff and get better, just because, for once, you can” – but it’s something she needs to drive her. That pressure helps form stories like her beautiful recent story in Island, “I.D.”

“I couldn’t be more excited about the future.”

The shift to creator-owned being the endgame for creators isn’t happening. It has happened. And it’s not just publishers like Image or Boom! leading the charge. Creators can do their own thing like never before. You can make graphic novels like Hicks. You can go digital first like Wyatt. Or you can even be a mad man like Martin. That’s the coolest part about all of this. While it’s not a sure shot you’ll be able to make a living going this route, creator-owned comics are more viable than ever. If there’s a will to tell your own stories, there’s a way. That’s a good thing for everyone.

“If Jack Kirby started his career these days, rather than in the Golden Age, he’d have started with creator-owned books, doing his own thing his own way. Siegel and Shuster wouldn’t have sold Superman for $130, they’d have kept it, and done it their way,” said Busiek. “Novelists don’t routinely sign away all rights to their material, and now that it’s more financially viable, this is how a lot of comics talent wants to do it, too.”

“There’s nothing wrong with doing work for hire, with writing or drawing the characters you grew up reading, but the notion that working on characters somebody else created is the pinnacle of success is a little backward. Dozens of different writers and artists contribute to long-running superhero titles, working on those books, as fun and as profitable as it can be, just adds your name to the list,” Stephenson said. “Creating something of your own is a chance to make a dent in the industry’s history.”

While there are outliers to any rule, deep down, everyone who reads comics wants one thing above all: good comics. What they are matters less than how good the comic itself is. Ultimately, the best work will come from creators invested in their work, telling their own stories because those aren’t just the stories they’re getting paid for. They are the stories they feel deep inside. The comics that move them. In this new ecosystem, we can have our cake and eat it too. We’re getting good new comics from all sides because forward momentum is more rewarded than ever.

“The question that I get asked a lot is ‘if you could work on anything, any comic book property, what would it be?’” Hicks said. “And honestly, at this point in time, I think I’d rather make my own stories.”

Telling your own stories has become the new endgame in comics. It’s been happening for decades, but it’s more true than ever. And as long as Hicks and her peers can make enough money that way, it’d be hard to see that as anything but a good thing.

Thanks to Kurt Busiek, Cliff Chiang, Faith Erin Hicks, Marcos Martin, Emma Rios, Jake Wyatt and Skottie Young for talking to me about the subject, as well as Eric Stephenson’s answers in the past. Want your favorite creators to succeed in telling their own stories? Make sure to pre-order at your local comic book shop. It makes a huge difference.

Header art by Michel Fiffe, Mike Allred and Laura Allred for the Madman 20th Anniversary Monster.