Fandom Is: On the Broken, Inescapable Nature of Fandom

As I get older, I find it increasingly difficult to not compare the way things are to the way they were. It’s natural to do, and perhaps why so many people are grumps when they get older. Everything changes and nothing stays the same, and that can be tough to deal with. That manifests itself in many different aspects of life – many of which are good! 1 – but the one I’ve been thinking of the most lately is what it means to be a fan.

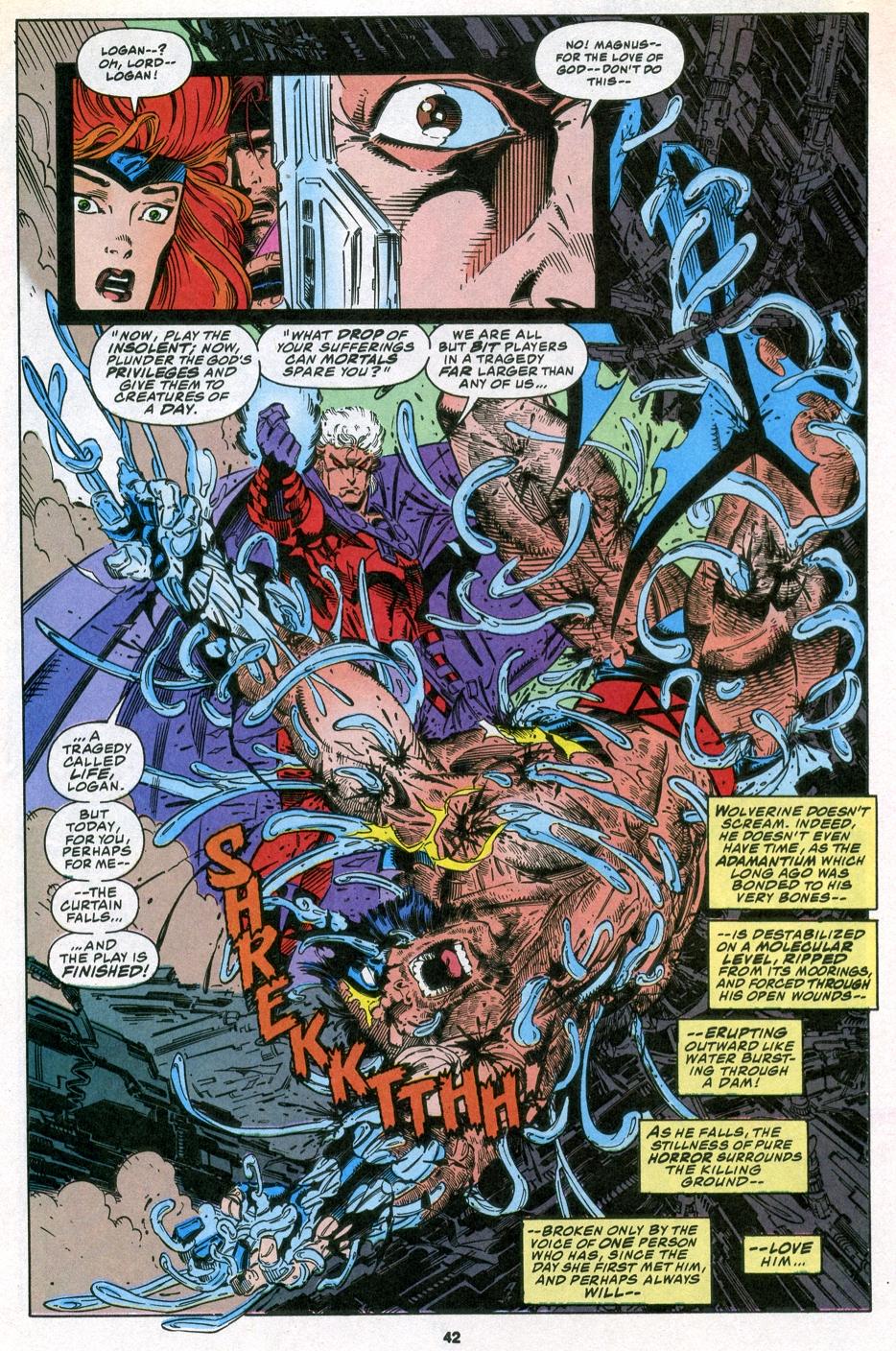

When I was a kid, my love of things was so pure. I accepted everything, even if it wasn’t how I wanted it to be. The death of Optimus Prime in Transformers: The Movie, Wolverine having his adamantium removed by Magneto in X-Men #25, the Indiana Pacers losing in the Eastern Conference Finals in seven games in consecutive years…these were all moments where my emotions ran high. Somewhere in Alaska, a youthful David Harper was apoplectic about how each story turned out. But I vividly, even positively remember them because of those emotions, and thanks to those memories, I learned to love those beats over time. That’s the wonder of youth: most of the time you just love things or you move on, and that’s kind of that.

Now, being a fan is something different altogether. Take Star Wars fandom, for example. There are so many different ways to “love” Star Wars these days that it manifests itself in artificial manipulation of user ratings on Rotten Tomatoes, harassment of actors, beheading action figures you presumably purchased yourself, 2 and any number of other negative behaviors simply because you don’t like a movie. When something new that was clearly impacted by that behavior arrives, which film you align yourself with becomes almost a partisan issue, an identifying characteristic that lets people know who you are simply through your preference of story.

These days, loving nerdy things has basically become the exact same thing as loving sports. DC vs. Marvel and The Last Jedi vs. Rise of Skywalker are variations on the Celtics vs. Lakers or Yankees vs. Red Sox, while things like The Snyder Cut or Abrams Cut become forever topics like the Harden Trade, 3 ideas that those who associate themselves with certain fandoms cannot help but wonder “What if?” about.

Of course, there’s a substantial difference between sports and movies, TV shows, comics or whatever format you take your nerdy delights in: there’s no inherently competitive element to loving something nerdy. That’s why the way fandom works in 2020 is so exhausting and honestly infuriating. The distance between loving and hating something has become non-existent, separated by an invisible barrier that leads to a complete overlap. No one hates stories like fans of those very same franchises, and we’ve seen that proven time and time again in recent years. In this one instance, I’m confident in saying something that will almost certainly make me seem very old: I haven’t changed, the way we love things has. It feels like fandom is fundamentally broken, and even worse, it’s become inescapable, a defining element of who we are and what we do.

It reminds me of a quote from Mark Russell and Steve Pugh’s The Flintstones #7 at DC Comics, in which The Great Gazoo – now reimagined as an alien sent to Earth to evaluate humanity’s odds of survival for a race of bookie aliens 4 – speaks to how our species operates now that we’re on top. Here it is:

“Survival has become easy for them. And life boring. They do their best to fill the void left by the struggle for survival. But nothing satisfies them for very long. So they just keep going back for more. Strangely, it’s when you give people what they don’t really want that they can’t get enough of it.

I think I know where this species went wrong. Human beings were never meant to be the top of the food chain. Their fears and anxieties served them well when they were prey. But natural predators are confident and lazy. They only kill as much as they need to survive. It’s only the nervous wide-eyed scavenger who’s always on the lookout for more.

Their voracious appetites were cute when they didn’t know where their next meal was coming from. But now they run the world, they devour everything in sight. And nothing can stop them. They self-destruct. Almost as if they know they don’t belong at the top of the food chain. They use fear to fuel their greed. And greed to justify their fear.”

I remember being floored by that when I first read it. This was a Flintstones comic, and it was nailing the destructive nature of consumerism and how it informs how we engage with the world around us. But those last lines in particular speak to some of the most notable ways certain segments of comic fans are doing what they can to sabotage the world around them, as this isn’t just a mass media kind of problem. This impacts every storytelling medium, big and small. Comics has seen the cost a locust swarm of bad actors can have on a medium, and the negative behavior it reinforces when it’s responded to.

The perfect example, of course, is Comicsgate. This informal campaign was designed to push back against shocking types like “women” and “people that don’t look or act like them” appearing in or making comics, 5 and their playbook was effectively the one Russell laid out in his script. Whenever someone rejected a Comicsgate talking point like America Chavez being a case of “forced diversity,” they programmatically point to its sales as a silver bullet for why fans didn’t want it. It didn’t sell, therefore, it had no value. Greed was justifying their fear, just like it was fear fueling greed when an assortment of ringleaders like Richard C. Meyer and Ethan Van Sciver created poorly conceived or long gestating 6 comic projects to grift shocking sums of money from their followers who were desperate to prove their buying power to comic publishers and, through that, how they are right and true.

Comicsgate was a manifestation of the worst parts of comics fandom, an exclusionary segment of people who believed that anyone that didn’t look or think like them doesn’t belong in comics and, beyond that, were actively destroying a medium they loved with their confusing ways. It created an atmosphere of tension at best and extreme harassment at worst, turning Comics Twitter into an outright war zone for quite some time. It’s down to a relatively quiet storm at this point, but still, Comicsgate looms. Even worse, they were doing all of this under the guise of passion for comics. This wasn’t hate fueling them; it was in defense of something they cared for, or so they said.

Of course, Comicsgate isn’t the only way this has reared its ugly head. Whether it’s through petitions to control or remove theoretically undesired narratives like Avengers Arena or DC/Vertigo’s Second Coming 7 or via targeted harassment of creators or editors when people disagree with a storyline, there are a whole lot of guilty parties. The distance between “not for me” and “shouldn’t exist” is shorter than ever, and many fans have little trouble letting publishers and creators know their thoughts. That’s not to say comics – or any story – should be untouchable, or that people can’t have complicated feelings. But there’s a level of reason I’d hope to see from people that often isn’t lived up to, even if I know this is the internet I’m talking about.

It’s a complicated subject for a number of reasons. Comic fandom 8 is a double edged sword, as the love we have for these long-running stories often comes from the same place negative behavior derives from. For example, many who read 2019’s House of X and Powers of X saw tremendous lift in enjoyment thanks to the enthusiasm X-Twitter 9 had for those two series that were one. The excitement that group spawned added to my own delight. It was like a comic shop on steroids each Wednesday on Twitter with the sheer amount of people enthusiastically talking about each release. The buzz was palpable and additive. But a few bad actors amongst X-Men fans 10 led to editors and creators being berated for choices made within the story before said decisions were even given a chance to truly play out, which was unfortunate to see. 11 As Jonathan Hickman suggested in an episode of Off Panel, every X-Men fan believes their favorite character should be the star of their own title. This naturally leads to a certain level of protectiveness and passion escaping into the public space. Good can come from that. But bad can as well. It’s a fine line, although I’d say X-Twitter is overall a positive segment of fans and the bad apples are few and far between.

I don’t want to let too many people off the hook, but the troubles with comics and fandom are often exacerbated by tensions at the core of the medium. One of those issues is how there is a finite supply of comics 12 – especially in an era of risk aversion at comic shops – which creates naturally competitive customer segments. There are the readers, the ones who are likely to come back the next issue, and then there are the collectors/speculators, or the ones that might return depending on certain variables. When a print run is low on a first issue, the latter group gathers like moths to a flame, which can make it difficult for the former group to buy comics at all. When the next issue comes out and the former group hasn’t read the debut and the latter group isn’t back because second issues aren’t as valuable, a book can tank.

Those different segments of fans are at odds with each other, and it creates a remarkably difficult path to success for even lower tier Marvel or DC books, let alone independent titles. Combine that with a distribution method that puts an inordinate amount of weight on consumers to pre-order, and you have the perfect storm to escalate tensions and give bad actors like the Comicsgate crowd ammunition to say, “See? These kinds of titles don’t work” when something a little different is canceled. It’s a push pull that affects comics of all varieties, and one that can lead to toxic behavior and harsh sales environments.

Then, of course, there are broader issues beyond what the comics industry itself presents. Social media plays a substantial part, as the old television news adage of “if it bleeds, it leads” has taken on new meaning in this era. Negativity plays well, and when a comic makes someone mad and an out-of-context panel is presented as irrefutable proof of its failings on social, it can lead to spiraling furor. Sometimes that’s fair – to a degree! 13 – and sometimes it isn’t, like when harassment is a result. But the piling on effect is real, and the siren songs of participating in magnificent ratios and quote tweeting to prove your worthiness can be irresistible. It also doesn’t help that Twitter is one of the worst places to have complicated, nuanced conversations. It rewards spice and often disincentivizes being reasonable. That’s no way to communicate complex feelings.

Pop culture sites exacerbate these issues as well. The way banner advertising works today has created a noxious content environment built on fanning the flames of outrage and propping up premises with extremely low levels of supporting proof. I’ve actually blocked several prominent comic sites on Twitter because of how they behave. A random writer from “SuperHeroNewz.ninja” saying their definitely real unnamed source inside Disney told them that the Abrams Cut of Rise of Skywalker exists or that Marvel’s first X-Men movie is coming but every character will now be anthropomorphic cats in the vein of, well, Cats, is not grounds for an article. Except it is for some, which leads to rage clicks, social media hullabaloo, and valuable impressions for said sites, which encourages more of it, starting the cycle anew. This isn’t a comic sites only thing, of course. But there’s a reason so much of the FilmClickbait Twitter account’s content stems from a small selection of notable comic sites.

All of this is connected. The way we engage as fans. Social media. The behavior of websites. It’s a circle, and an often ugly one at that. And it acts as an anchor on the things we love, whether you’re talking giant media empires like Star Wars or the smallest of indie comics. Toxicity from core audiences is a first step to gatekeeping, 14 escalating bad behavior, and potential fans choosing to ignore a medium altogether. For example, if you were a woman or person of color, why would you ever want to dive into comics when what awaits you is harassment and the endless questioning of your fan bonafides? It’s simple: you wouldn’t.

That’s one thing that hasn’t changed since my youth. While there are more people than ever that look and think differently than me engaging with comics and other nerd-centric storytelling mediums, many of them have found homes in other channels, like graphic novels through bookstores and libraries. It’s likely part of the reason the book market is poised to slingshot past the direct market when the 2019 numbers come out: it’s the hardcores versus everyone else. And everyone else is winning. 15

Of course, it’s always worth remembering that there is a flipside to all of this, and the fan groups that generate more interest in something or foster positive conversation are hugely important. Those still exist and are often impressive in reach and impact. X-Twitter is a good example. So are two segments borne from the broader web of sports and pop culture site, The Ringer. Mallory Rubin and Jason Concepcion’s Binge Mode podcast is a perfect example of the fierce power of fandom, and how – not to be cheesy, but it fits the stories they’ve examined so far – your love of something can overpower hate any day of the week. It’s a wonderful group. Meanwhile, Shea Serrano’s FOH Army 16 is maybe the single most positive force on the internet. They don’t just power Serrano’s books to the top of the New York Times Best Seller list; they create titanic successes in charitable giving and support for people and businesses that need it thanks to Serrano’s guidance.

These groups are remarkable examples of the positive power of fandom, and they’re not alone. There are still huge swaths of people who just love stories and that’s that. But there is undeniably a cost to the bad behavior of fandom. And Pandora’s Box has been opened. The Rise of Skywalker’s seemingly reactionary nature, story-wise, sends a clear message to these bad actors that their public sulking and rage can generate real change. It’s possible this only continues to worsen, and the lines drawn between fans go from being depicted in pencil to boldly drawn in pen. It’s weird to think of where this could lead. Maybe we have an absurd future like Greg Rucka and Michael Lark’s Lazarus in which countries are formed around our fandoms instead of the corporations we find ourselves under. I hope not, although that does sound like a fascinating book. 17

This all brings me back to The Great Gazoo. Towards the end of his report in The Flintstones #7, he admits to his bookie bosses that the odds are stacked against humanity. As he tells them, “This species will probably be a one-off. An embarrassing asterisk in the history of an otherwise promising planet. I would put the betting odds against the human race at 25:1.” Maybe that’s what fandom is looking at as well – long odds that we’ll overcome the rifts formed by the things we love, and a future where these stories separate fans instead of unite them.

I’m hopeful for something different, though. Like The Great Gazoo concludes with, maybe I’m missing something, and maybe what defines fandom isn’t the vocal group that chooses rage but those that love what they love and are fine with the things that aren’t for them. I’d like to think that, as there’s a whole lot of good out there, and plenty worth celebrating.

I for one am thrilled I can read basically any Marvel comic ever thanks to my Marvel Unlimited subscription, for example, ignoring hundreds or thousands of far more important examples of social change.↩

Which lowkey may be the craziest thing to do of those three, even if isn’t the worst.↩

A much analyzed deal in the NBA in which the Oklahoma City Thunder dealt future league MVP James Harden away for a relative pittance – shouts to my guys Steven Adams and Jeremy Lamb! – because they didn’t want to pay him a minor sum relative to his value.↩

That’s a heck of a series. I highly recommend it, if only for how it reimagines old ideas.↩

This is an extremely dude heavy group. Not to paint with broad strokes, but a lot of these groups seemingly are.↩

I have no idea if Cyberfrog: Bloodhoney even came out.↩

Both of which are good comics. Unfortunately, the latter effort even proved successful, as Second Coming was ditched by Vertigo before launch, leading to its eventual rescue by AHOY Comics.↩

Or really any fandom.↩

Or the title the significant group of X-Men fans on Twitter have taken on.↩

Incredibly, specifically, Jean Grey fans it often seemed, whose number is significant and passion is as potent as the Phoenix itself.↩

Thankfully, a Terminator sent from the future to withstand sassing from X-Men fans was hired as the lead writer of the line.↩

Ignoring digital comics, of course.↩

Saying “this is bad” is fair. Condemning those involved and making bold assertions about their character in many cases is not.↩

As proven by this recent and legendary tweet by a Star Wars “fan.”↩

As they should be!↩

Or Fuck Outta Here Army.↩

Don’t steal that idea!↩