“Just Do Your Thing”: The Story Behind the Making of Marvel’s Strange Tales Anthologies

One of my favorite titles from Marvel’s past is What If…? Its premise is simple. It takes a specific moment in time from Marvel’s history, a fulcrum point from which a character or title changed forever, and flips it in the other direction, effectively turning fan conversations into out-of-continuity stories. Given that Marvel superheroes largely have existences steeped in tragedy, it’s an idea that has considerable, seemingly inexhaustible depth to it, which might be the reason there have been 13 volumes of the series so far.

Stories like “What if Gwen Stacy had lived?”, “What if Uncle Ben had lived?” and, well, “What if Elektra had lived?” 1 envisioned another reality, one where things had changed, but not always for the better. These stories often suggest that the reality we know in the Marvel Universe is, believe it or not, the ideal result and the way things had to be, despite the aforementioned frequency of misfortune.

I love it, because honestly, who doesn’t wonder about the way things could have been if they had just played out a little differently? Hypotheticals are great, but to see the potential of an idea played out in comic form? That can be even more interesting. 2

While not a What If…? by name or even execution, the 2009-10 Marvel anthologies Strange Tales and its sequel Strange Tales II remind me of that oft-recurring series. And that’s because the publisher dared to ask a very unexpected question within it: what if indie and alternative creators ran Marvel? What would the stories of the Hulk, Captain America, the X-Men and any number of other fan favorites be like then?

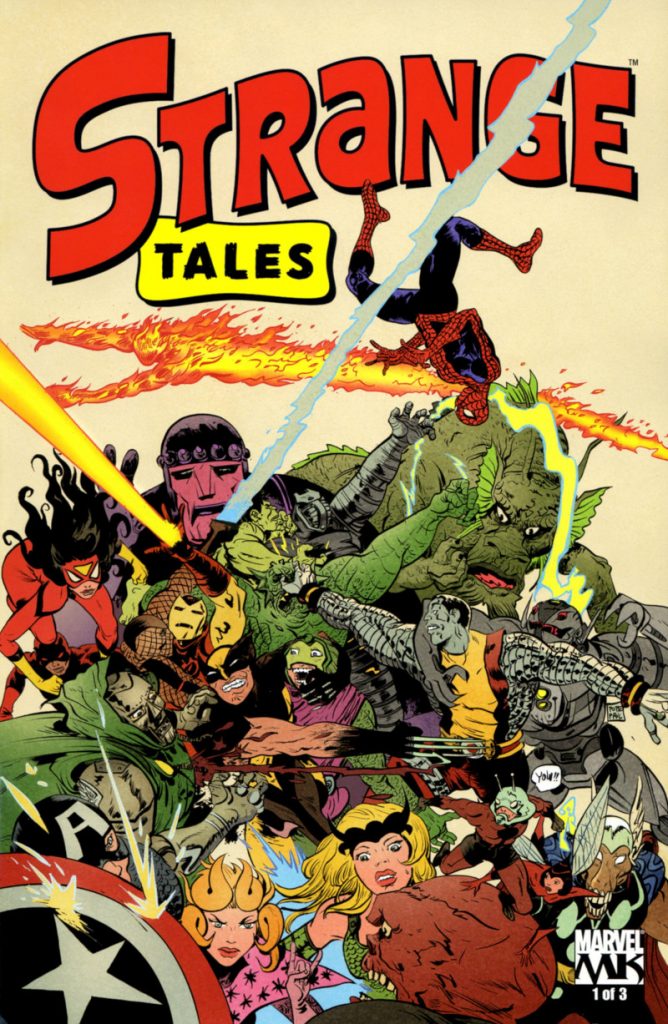

Paul Pope’s cover to Strange Tales #1

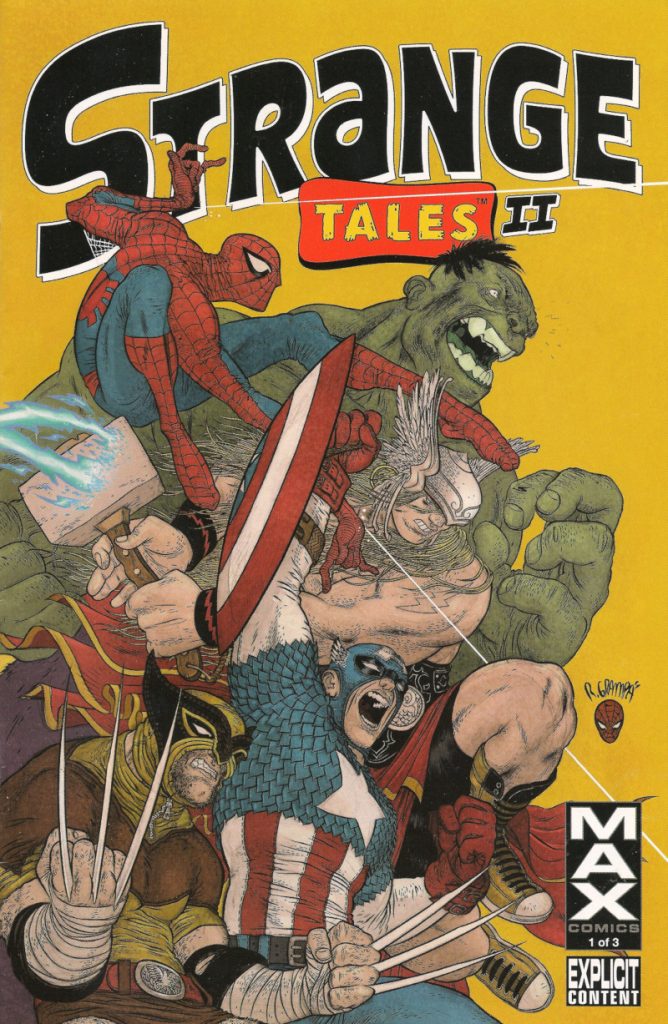

Rafael Grampa’s cover to Strange Tales II #1

It’s a fascinating question, and unlike similar titles from throughout superhero comic history, 3 this series primarily tasked cartoonists – or creators who write and draw their own work – to tell these tales. That’s a crucial distinction, as each piece wasn’t just a short from a somewhat randomly assembled collection of creators, but a real insight into the stories these titans of the form might have told if things had played out just a little bit differently for them.

The cartoonists made it an A-list affair, with a lineup that included *takes a deep breath* Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, Kate Beaton, Nicholas Gurewitch, Paul Pope, Nick Bertozzi, Peter Bagge, James Kochalka, Jason, Jhonen Vasquez, Rafael Grampa, Stan Sakai, Becky Cloonan, Jonathan Hickman, Jeff Lemire, 4 Michael DeForge, James Stokoe, Dash Shaw, Gene Luen Yang, Ben Marra, and many, many more.

Not only that, but they were hired to do something rarely seen at the publisher: make exactly the kind of Marvel comic they would create, with effectively zero editorial oversight. While not every story was every reader’s jam, it was a rare experience that meshed superhero characters with creators who rarely worked in that world, pairing wonderfully offbeat ideas with these immensely famous creations to outrageous, delightful effect. In short, it was like the process of a creator-owned project set in a for-hire universe in the purest version of that idea.

Series editor Jody LeHeup told me it was “an opportunity to kind of build a bridge between two worlds,” resulting in one of the most atypical, unexpected comics from the history of the publisher. And it was brilliant because of it.

Naturally, with such an anomaly, I was curious: how did such a thing happen? How did a publisher known for enormous events, often labyrinthine continuity, and occasionally militant character management get into the business of telling the stories of Kraven the Hunter finding a date for prom, Galactus using Magneto as a refrigerator magnet, and Uatu the Watcher visiting a strip club? The short answer is it took a small group of champions, a fateful office visit, and a whole lot of wrangling. The long version is what we’ll be diving into today.

The story of Strange Tales begins with former Marvel editor Aubrey Sitterson. While you might know him as the writer of Dark Horse’s No One Left to Fight, Sitterson had a potent three year stretch at the House of Ideas in both the Marvel Heroes and X-Men offices, working on titles like Civil War, Captain America, Wolverine, X-Factor, just to name a few. While he worked on several notable projects – certainly ones far more famous than the anthology we’re focusing on – Strange Tales was a special one, if only because this truly was his baby, at least for a time.

“As I remember, it was Aubrey who came up with the idea,” former Marvel editor and current IDW editor-in-chief John Barber told me. 5 “I think he cooked up some of the details with Tom 6 and took it to the Marvel pitch meeting.”

It was approved, and while others like Brevoort and then Marvel senior editor Axel Alonso were interested in comics outside the superhero set, Barber suggested that he and Sitterson “were the guys at Marvel who were reading the most indie, alternative comics.” That made them the leads on the title, even if it truly was Sitterson’s project.

“Aubrey and I would go to small press shows and just pick up new stuff,” Barber said. “So it was like Aubrey’s show, but he and I would talk about it sometimes.”

Sitterson started developing it in earnest from there, recruiting key players like Stan Sakai and Dash Shaw and getting the first volume of the series well down its production path. But it was always a tenuous fit at the publisher. Former Marvel editor Jody LeHeup – whose role on the project we’ll get to in a minute – noted that “there were individuals” at Marvel “that didn’t think it was worth the time and effort to put it together,” and that there were concerns some of the eventual work could be “too off model.” Barber recalled internal fears that it could be believed they were making fun of Marvel characters, 7 a perception that they thought could impact potential movie deals. 8 Ultimately, LeHeup believes it won out for a simple reason: because it was a project that benefited everyone, endearing “Marvel readers to indie creators” and “the fans of indie creators to Marvel comics.”

“I think everybody knew that the Strange Tales anthology wasn’t going to be a huge seller, necessarily,” LeHeup told me. “But, it seemed worthwhile, and I think everybody who is a fan of comics as a medium felt the same way.”

The problem was, Sitterson departed the company well before Strange Tales ever saw the light of day. The erstwhile editor left Marvel in May of 2008, nearly a year and a half before the title’s debut. This project largely existed because Sitterson was its champion. Without him, it needed another one. While Barber wasn’t that person, he built the bridge between the editor who initially developed the project and the one who carried it through the rest of its existence.

“(Sitterson) left, and it fell into my purview,” Barber shared. “My biggest job was not getting it canceled during that time. That was the biggest accomplishment I had.”

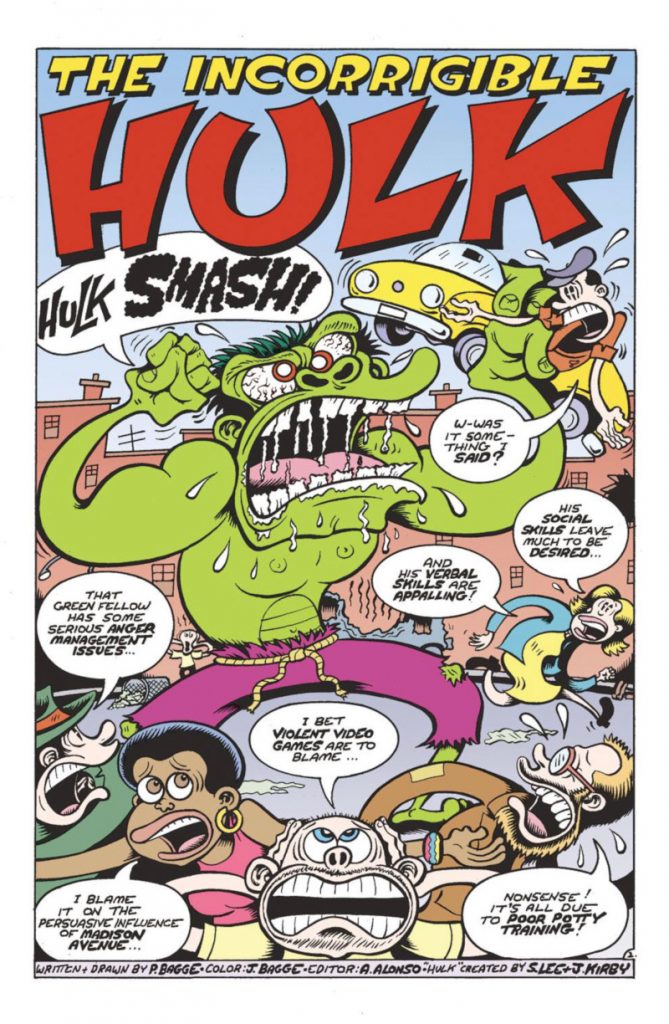

Barber recalled that the prevailing attitude at the time was that Marvel should just cut its losses on the book, so he knew he needed another ally. To do that, he turned to Alonso with a very strategic suggestion. He knew his fellow editor loved the work of cartoonist Peter Bagge, having worked with him on The Megalomaniacal Spider-Man before. He also knew the cartoonist had created a follow-up story called The Incorrigible Hulk that was caught in limbo for the same reasons Strange Tales was an awkward fit at Marvel. He saw an opening there.

“I remember going to Axel and saying, ‘You know what we need to do is get that Hulk story in here,’” Barber said. “So that kind of got Axel onboard. This story that he had edited would finally see the light of day.”

With Alonso on his side, the book was in a safer place, especially after Barber’s other main contribution: reformatting it to become a three-issue series.

“I remember going through some Excel spreadsheets and reformatting it because they were afraid if it was going to be four issues, it was going to not be selling by issue four,” Barber shared. “I figured out a way to reformat it into three longer issues, but it actually increased the page count, so we had to get new stories in there.

“That was a move I was always proud of. That we got more stuff in there when they were trying to cut it.”

At that point, the person who did the bulk of the work compiling the series was onboard: LeHeup. He’s mostly known as a writer these days, as you can find his exemplary work in Image titles like The Weatherman and Shirtless Bear Fighter, but back then, LeHeup was hired by Barber as an assistant editor at Marvel. Like the title’s two initial guides, LeHeup was a fan of comics of all varieties. And one fateful day, he came across what Sitterson had managed to put together at Barber’s desk, as his boss often would hang active projects on his wall to keep them top of mind.

“I’d always go over there and be like, ‘What (is this)?’ And I picked it up one day, flipped through it, and I was like, ‘Oh my god,’” LeHeup said. “It wasn’t at all what it ended up becoming in terms of the page count of it all. There was still lots to do.

“But there was enough there that you could sort of see what he was putting together.”

At that point, somewhere between a third and half of the first volume was together, with LeHeup suggesting that “some stories were intact” while “some of them were just blue lines or a script.” Recognizing an enthusiastic inheritor of the project when he saw one, Barber handed it off to his direct report. From there, LeHeup got to work filling out the rest of the book based off the infrastructure Sitterson established. But before he did that, there was one key change he wanted to make. While his memory is hazy, LeHeup believes the project was originally titled “Marvel Underground,” and he knew there was a better name for it.

“It occurred to me (that) we can reinvent Strange Tales,” LeHeup told me. “Nobody was doing anything with that title, so it seemed like a no-brainer, because these are some really strange tales. That just ran up the food chain and people were like, ‘Yeah, go for it.’”

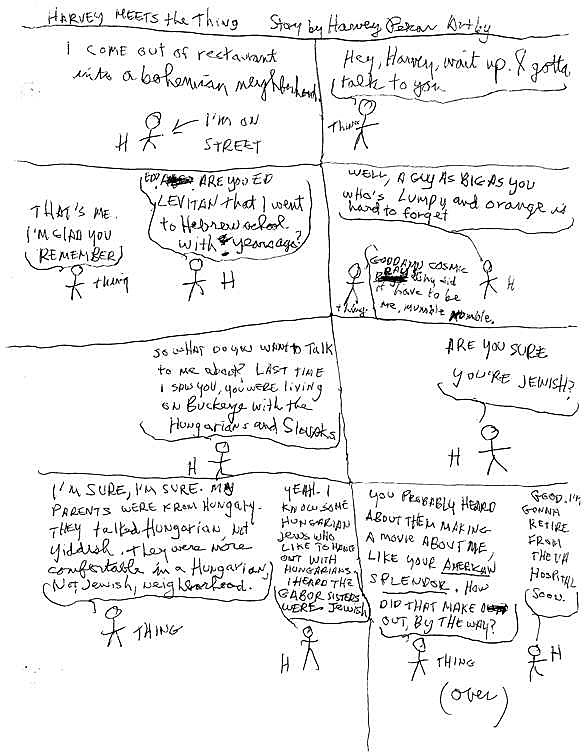

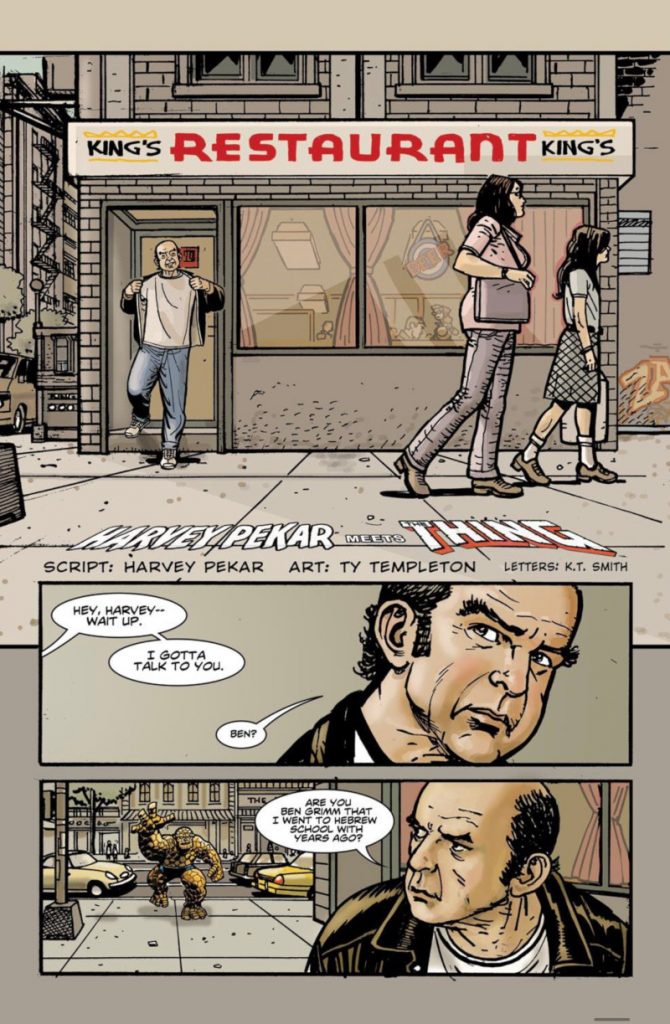

A page of Harvey Pekar’s script for his story from Strange Tales II #3

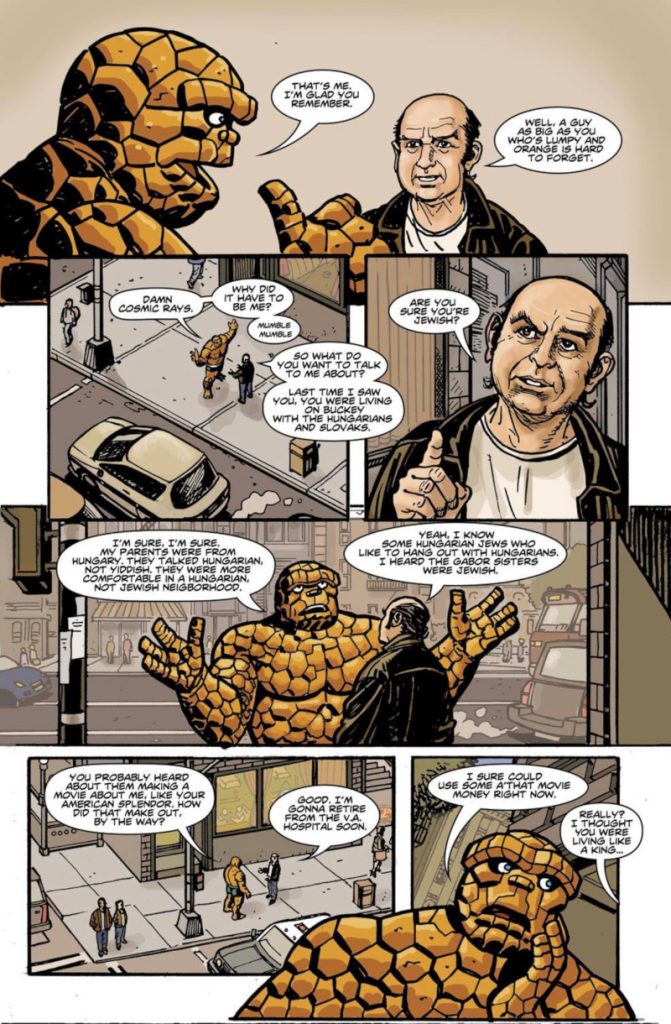

From Harvey Pekar and Ty Templeton’s Strange Tales II #3 story

From Harvey Pekar and Ty Templeton’s Strange Tales II #3 story

When it came to creators for the project, the varying editors were looking for a mix of newer voices and legends. Barber said it was important to them to bring on both “classic alternative creators” like Harvey Pekar and Los Bros Hernandez but also relative up-and-comers like Jeff Lemire 9 and Dash Shaw. Given that LeHeup was newer to the team, he sought help from people who had connections with the types of creators he was looking for. That meant reaching out to Eric Reynolds, the Associate Publisher at Fantagraphics. LeHeup described Reynolds as “a big help,” with the veteran comics man guiding him towards creators he was already looking for as well as new voices he might not have been aware of.

LeHeup suggested “that in all of (Reynolds’) years working in comics, no one at Marvel had ever reached out to him.” When he told me that, I found the idea to be impossible. Reynolds had been working in comics since the 1990s. Surely that couldn’t be true? It was, though, as Reynolds confirmed to me that no one at Marvel had ever spoken to him in an official capacity before then. He insisted it wasn’t because of any rivalry, as he said that’s “like saying Marvel Studios is in competition with Criterion Films.”

“I was down to help because I want to help creators that I work with,” Reynolds shared. “This was a good, paying gig that I was happy to help authors I work with get, if it was of interest to them. It could also be a very fun gig for the right cartoonist.”

Reynolds wasn’t the only help in that regard, as journalist Sean T. Collins also assisted LeHeup, with Collins aiming for a “blend of ‘alternative cartoonists whose comics I enjoy’ and ‘alternative cartoonists I think would do a good job with Marvel characters,’” when he sent names Marvel’s way. Both Reynolds and Collins earned special credits in the comics for their contributions, but as Collins told me, his “main involvement was after the fact,” as he interviewed nearly every contributor from the title for Marvel’s site and wrote the bios that appeared in the comics.

“It’s still wild to me that it made it to the stands intact!” Collins shared.

Given that the series ultimately “did well enough” that both LeHeup wanted to do another volume and that Marvel supported a sequel, the editor had a whole lot of space to fill. Now, as previously noted, this project had an incredible list of creators involved. That much is undoubtedly true. But the lineup of those who declined to participate is perhaps even more astonishing. LeHeup shared that he asked David Mazzucchelli, Dan Clowes, Chris Ware, Charles Burns, Adrian Tomine, Al Columbia, Al Jaffee, and Dave Cooper, just to name a few. All declined, for one reason or another. 10 When I suggested LeHeup was very much shooting his shot, the editor said that was key to getting the creators who eventually did participate.

“By shooting my shot, we ended up getting some folks who I didn’t think were going to say yes,” LeHeup told me, specifically noting Jaime Hernandez and Jason, for two. “I always approached my editing – and my writing career, as well – as it’s worth the ask, you know? Just check and see. You don’t know. There might be something you can work out.”

And work out it did. The appeal was obvious to most who agreed. Nearly every Strange Tales creator I spoke with had warm feelings towards characters and comics from Marvel’s past, from newer names like Ben Marra and Shaw to legends like Sakai. The rich history of the publisher impacts people from all walks of life and parts of the world, including someone like John Arne Sæterøy, also known as Eisner, Harvey and Ignatz Award winning cartoonist Jason.

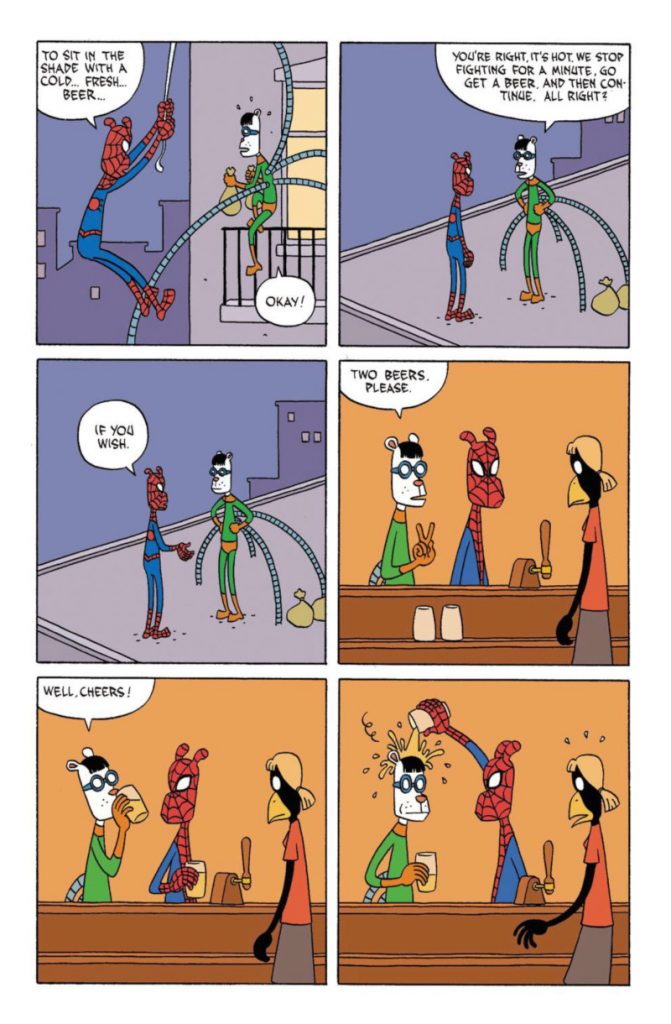

“I grew up reading both American and European comics translated into Norwegian,” he told me. “So, from DC there were Batman and Superman and from Marvel there were Spider-Man and Fantastic Four, and later Hulk and Daredevil, as well. I enjoyed Spider-Man a lot, the fact that he was a young man and had all sorts of personal problems. I could relate.”

In his youth, Jason would copy drawings from Spider-Man, with the cartoonist being particularly fond of the Ross Andru drawn issues. LeHeup recalls finding it incredibly exciting that this legendary creator was so nostalgic for the character, if only because of how unexpected it was.

“Other people are nostalgic about things too, but something about Jason being nostalgic for (Spider-Man) was exciting, because his work doesn’t convey that sense that he would be nostalgic for superhero comics,” LeHeup told me.

Everyone had their reasons, from the Marvel connection to more personal ones like Shaw and Sitterson growing up in the same city and Sakai’s adoration of Steve Ditko. But my favorite one came from Lemire, who at this point had never worked on a Marvel or DC title, and was mostly famous for his work on graphic novels like Essex County. When he was offered the job, he thought he had to take it for a simple reason: he never knew if he’d get another shot.

“Up until then I had only done indie comics and never thought I would work for Marvel or DC in a million years, but obviously I loved those worlds and characters, so it was a no-brainer,” Lemire said. “I saw this as my one chance to actually draw one of their characters in print.”

While Lemire obviously has had many, many chances to work with Marvel’s best and brightest, not everyone would have the same opportunities after Strange Tales. For the bulk of those I spoke to, this was their one shot for all they knew. They were eager to take it.

Barber noted that there were two names involved with the project who may not have earned as much awareness amongst the general populace. He was correct. Even I, a person writing a history piece on these titles, missed this. A great looking comic on the inside would only go so far, but they knew it needed to pop on the covers too. While they had luminaries like Paul Pope and Rafael Grampa providing art there, two of the very best designers in the business did the rest, with Chip Kidd designing the covers and Rian Hughes crafting the logo. With that, the effectiveness of its outside was locked in.

Now they just had to make the rest work.

One of the best decisions Sitterson and then LeHeup made in the development of this project was to empower those involved. These were cartoonists who were used to telling their own stories, and to help Strange Tales become the best version of itself, the editorial team gave everyone involved a rare level of independence. As LeHeup told me, “I didn’t offer any editorial guidance aside from just, ‘Do your thing.’”

“It’s really just the stories that those folks wanted to tell,” he added. “I had the good sense to just get out of their way and let them do that.”

While there were some very basic parameters – namely, it shouldn’t be pornographic, loaded with cussing, or fundamentally against character – LeHeup wanted everyone involved to “more or less do anything (they) wanted.” Lemire loved that, he recalled.

“We had total freedom. They were hiring us to be us. They wanted the Marvel Universe filtered through the characters voices completely, which is sort of the opposite of how work-for-hire often ends up, where they want you to bend your voice to their universe,” Lemire said. “It was very much like doing a creator-owned project. I just did it my way and didn’t get any notes or anything like that.”

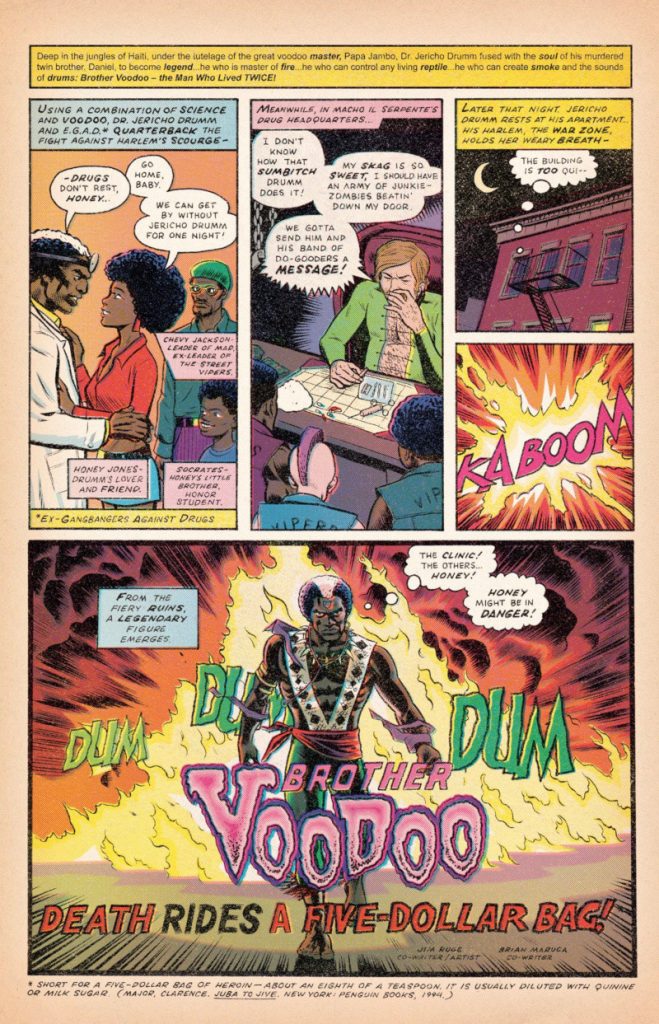

While nearly everyone I spoke to effectively did whatever they wanted, there was one exception: Jim Rugg. He had the toughest path to completing his story, a Brother Voodoo tale that fused the cartoonist’s love of Gene Colan with the energy Rugg had brought to his then-recent graphic novel Afrodisiac with his oft partner Brian Maruca. Unexpectedly, that story was rejected – Rugg told me he can’t even remember why that was, but he did note “one of the villains snorted a pile of cocaine” before adding, “but he was a villain” – and from there, the pair crafted three additional stories in hopes of finding a fit for the anthology. When LeHeup came onboard, though, he wondered why the first one didn’t work.

“I was reading the Brother Voodoo story and I’m like, ‘I don’t get it. What’s wrong with this?’ There’s a bit of chasing down what the problem was to begin with,” LeHeup said. “And then getting some really specific answers about that, bringing it back to Jim and being like, ‘Hey, I think we can publish this also if we can do X, Y, and Z,’ and he’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, I could do that.’”

Besides that, though, it was smooth sailing for the creators I spoke with. 11 This freedom allowed the creators involved to take these world-famous characters in unexpected directions from a story and character standpoint. I wanted to quickly go through a few favorites, and we’re going to start with my top entry from the two volumes, a Spider-Man story by Paul Maybury. The cartoonist derived his entry from what he described as “a leftover childhood observation.” Simply put, it attempted to answer this question: how did Spider-Man explain away his injuries when he was just regular old Peter Parker?

“It’s a silly comic but I treated the visuals with a degree of seriousness,” Maybury said. “My short was an earnest attempt at crafting a good Spider-Man story. Marvel helped me make the comic I wanted to make.

“I still look back on the project as a whole, fondly.” 12

That childhood idea combined with the cartoonist’s serious approach led to a story that was equal parts poignant and hilarious, with its very narrative-driven approach setting it apart from its peers in the eyes of LeHeup himself. It’s something that is brought up to Maybury regularly, all these years later.

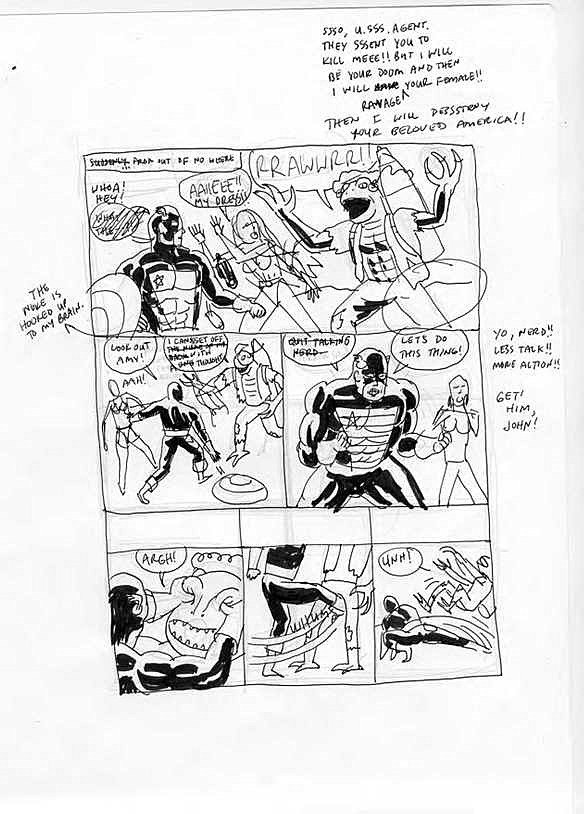

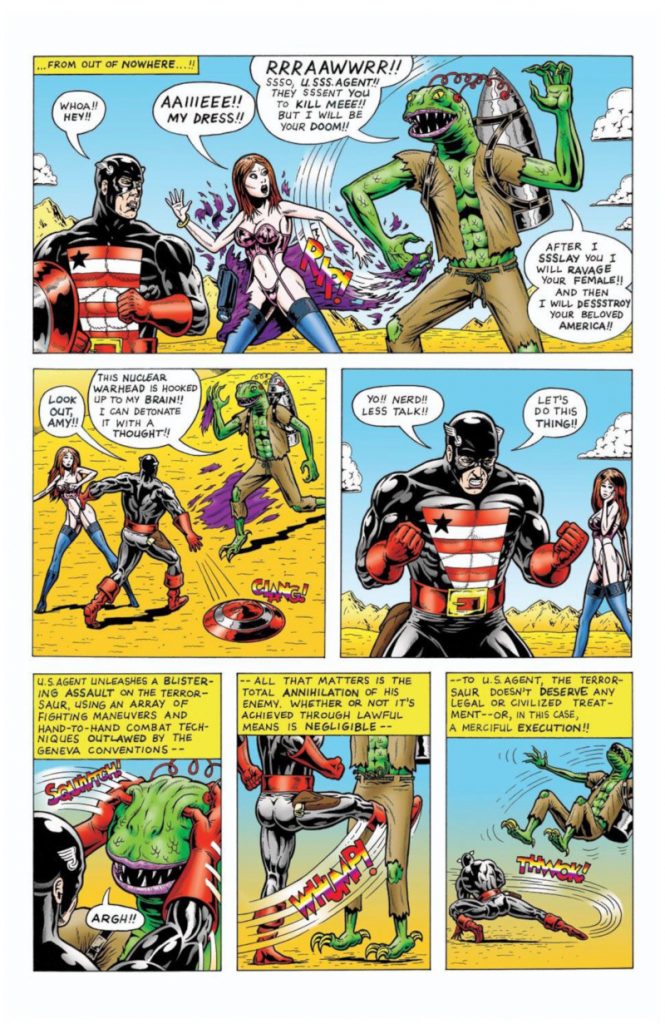

Ben Marra’s layouts for his Strange Tales II story

A page from Ben Marra’s story from Strange Tales II

Cartoonist Ben Marra is a football fan, and when he originally pitched LeHeup, he wanted to work with the only football themed hero from Marvel’s history: NFL SuperPro. His hope was that he could redeem the character after years of thriving on listicles making fun of bad superheroes. His plan to do that was pure madness and glory at the same time.

“My idea was for NFL SuperPro to be hired by the CIA to go assassinate Osama Bin Laden, who at the time was still alive and believed to be living in Afghanistan,” Marra shared. “The twist would be that NFL SuperPro would use all these illegal football moves to kill Bin Laden. Illegal hands to the face, chop block, clipping, horse collar, face mask, etc.”

Unfortunately, this character, whom Marra thought was “both an idiotic and awesome concept at the same time,” was no longer owned by Marvel. The story didn’t happen for that reason, but after a number of false starts with other characters, Marra ended up with the same plot starring a different character: U.S. Agent.

“He’s a good replacement for NFL SuperPro because he’s kind of a deluded jock, dickhead the same way I envision NFL SuperPro’s personality,” Marra told me. “I did pretty much the same story as I originally planned but substituted out the primary elements. NFL SuperPro became U.S. Agent. Osama Bin Laden became The Terror-Saur. Instead of illegal football moves, U.S. Agent uses martial arts moves prohibited by the Geneva Conventions.”

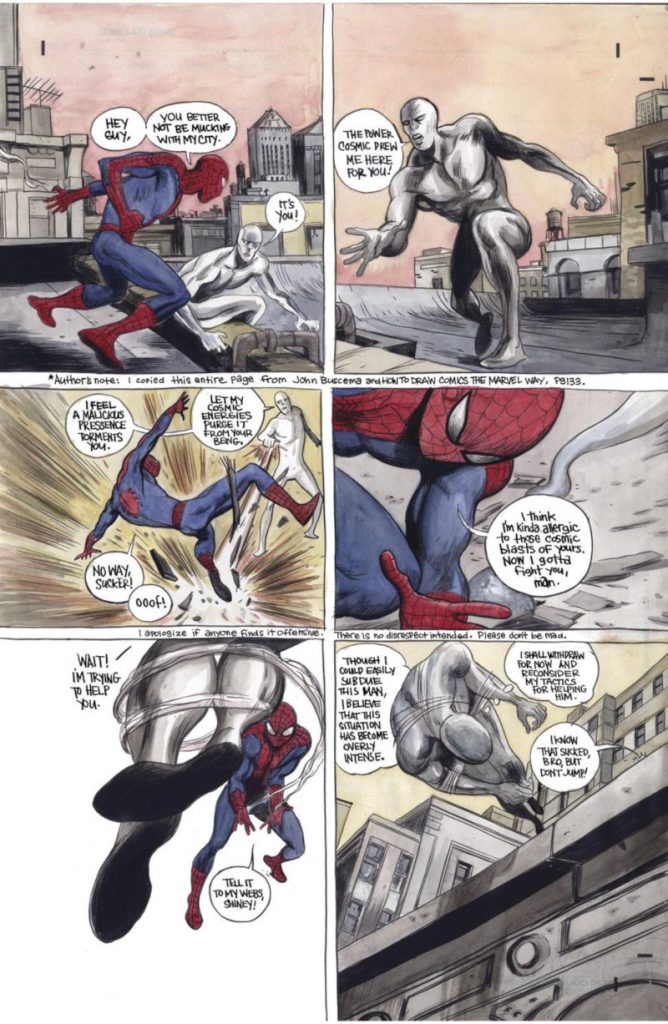

Farel Dalrymple’s idea was ingenious, as he looked to a seminal art book for inspiration. He was a huge John Buscema fan, and he decided to redraw a specific page out of How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way where Silver Surfer is fighting Spider-Man, but as a middle page of his story. From there, he asked himself, “Why would these guys be fighting?” a question that led to a natural expansion both forwards and backwards from that point. Pair that with an infusion of “Peter Parker neuroses” and the cartoonist’s own complicated feelings with his former home of New York, and what you get is a gorgeous, totally unique tale from Dalrymple. 13

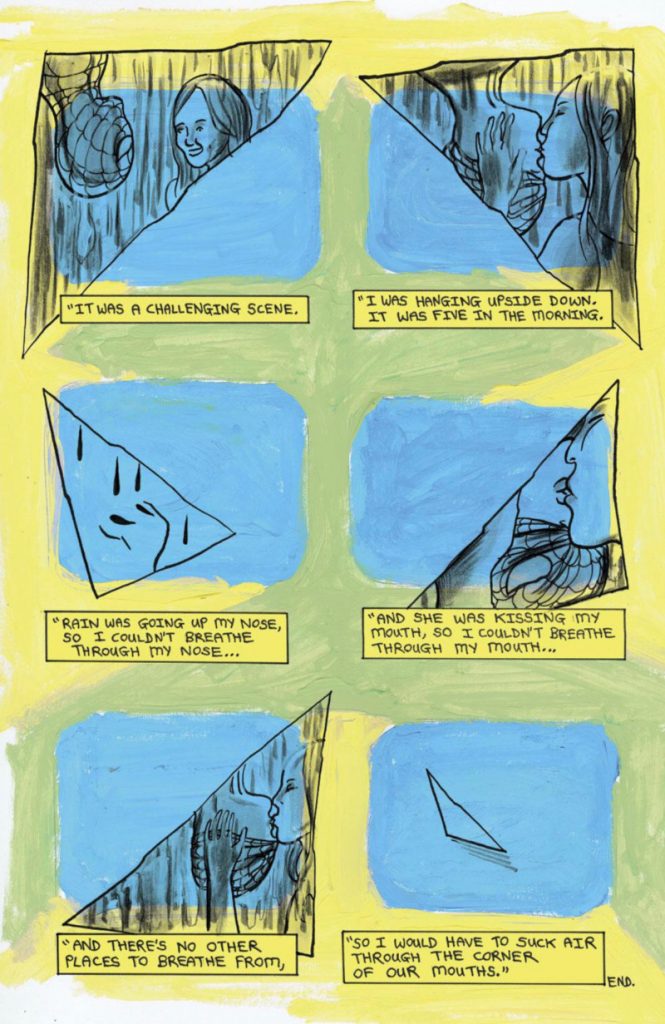

The last entries I wanted to highlight were Shaw’s, one of the few creators who worked on both volumes. Both of his entries starred Steve Ditko creations – the first was a Doctor Strange vs. Nightmare tale while the second saw Spider-Man and Mysterio square off – and that was for a very specific reason: Ditko is one of Shaw’s most beloved storytellers.

“To me, Ditko is on the level of William Blake as a great visionary artist and writer,” Shaw shared. “And part of what is amazing about seeing the popularity of these characters is that the power of the Ditko and Kirby still shine through, no matter how much others may attempt to degrade it or alter it.”

Shaw recalled an experience where he caught a Spider-Man cartoon, only to be amazed by how – despite its shift into another medium – Ditko’s abilities as a “great visual inventor” were still present on the screen. The cartoonist was much happier with his second story, a thoughtful, haunting, and incredibly original Spider-Man comic, as it fused an early Ditko character with how the legendary creator crafted his own personal work later on. Much of that story stemmed from emotions Shaw had living in New York when Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man films were coming out, as he often wondered how his fellow New Yorker Ditko felt about seeing this character he co-created everywhere he went.

“At that time, it just seemed totally crazy that this comic culture was really mainstream and that this very singular individual who I knew lived alone in Times Square, making these self-published works, was behind this giant global phenomenon,” Shaw said. “So I remember thinking about what it would be like to be Ditko stepping out of the subway and seeing his character twenty stories tall.”

“And it’s almost like his mind, his views of the world are being reflected back at him in this probably scary way,” he added. “I mean, I can’t pretend to know what he was thinking, but I would wonder. I would wonder, man, what is it like to be him right now, stepping outside and seeing your character reflected back at you at this enormous scale.

“Maybe the story had something to do with that.”

That connection is underlined on the story’s final page, as all of the narration on it came from an interview Tobey Maguire did about how weird and kind of gross the experience of kissing Kirsten Dunst while upside down was in the first Spider-Man movie. The cartoonist wanted to “pair that ecstatic image” – the iconic shot of Spider-Man kissing Mary Jane – “with the reality of it,” perhaps in a not entirely dissimilar way that Ditko connected with imagery from the movies.

It’s a remarkable work, but honestly, that’s where the wonder of these stories come from. When you have talents like Shaw or Maybury or Dalrymple or whomever and you turn them loose with these world-famous characters, it broadens the potential of what Marvel stories could be.

They could be something like Jason’s Spider-Man tale, where the cartoonist explored his own realization he had never been in a bar fight. Or maybe it’s like Dean Haspiel’s perfectly titled “The Left Hand of Boom” story, in which he fused his favorite Marvel hero – The Thing – with Marvel’s “worst character” in Woodgod. Or even a quiet, beautiful work like Sakai’s Samurai Hulk story, which he intended as a tribute to Stan and Jack rather than a parody. Marvel comics could be anything in the hands of these talents. You just never knew what you were going to get.

But you knew one thing about Strange Tales: that what you get wouldn’t be boring, and it would certainly be unlike anything else you might find at Marvel.

When you read Strange Tales or Strange Tales II today, they feel just as fresh and exciting as they did a decade ago. This project was both great and had longevity, something that can easily be a struggle in the churn and burn world of superhero comics. But by divorcing itself from canon, this anthology became something special in an atypically lasting way.

“Superhero stories can get really complex. But also, a lot of superhero comics are comics about comics,” LeHeup said. “That’s, I think, one of the things that’s refreshing about a lot of the Strange Tales stories is that they aren’t really.”

Beyond that, LeHeup noted that these cartoonists managed to tap into an element that’s important to Marvel, but rarely focused on to this degree. That’s the idea that superheroes are also super humans. If anything, that aspect has only become more important today, as so much of the fandom of superheroes now – particularly with the growth of the Marvel Cinematic Universe – is about playing that old “What If?” game with the personal and internal lives of these titans. And who would be better at doing that than a collection of the finest cartoonists in the world?

“One of the things that’s so great about these creators is that they hyper humanize everyone, you know what I mean?” LeHeup said. “It’s hilarious, it’s fun, and it’s endearing. This (is what) the anthology’s all about.”

The fascinating thing about Strange Tales is it’s only become more fitting in this era, and yet there’s been little indication that something like it could ever come our way again, especially as management of intellectual property has only become of a greater importance. That’s a shame, as Haspiel said something many creators agreed with when he told me, “I wish Marvel would publish more projects like Strange Tales.”

At the same time, I’d argue its impact has been felt since then. Both Barber and LeHeup concurred with me that, to a degree, Strange Tales almost operated as a tipping point for eyes being opened at Marvel. Some of the names from the project became gigantic successes at the publisher since then, including Becky Cloonan, Jonathan Hickman, and Lemire. Even if the anthology itself doesn’t persist, names from the book and aspects of its storytelling approach carry onwards at the House of Ideas. 14

To a degree, it’s almost a chicken and the egg situation. As LeHeup asked me, “Is it editors who are influenced by stuff like Strange Tales, who feel like there’s a little bit more room to explore, and find some more stylized creators? Or is it the creators themselves, just the pool of them became more diverse?”

It’s hard to say, but it feels there was an impact there, even if Marvel was initially less than thrilled about the project. Thankfully, it had a trio of champions to carry it through in its founding father, Aubrey Sitterson, its caretaker in John Barber, and the one who brought it home in Jody LeHeup. Their tireless work prevented it from becoming a What If…? moment from the history of Marvel, a forgotten instance of what could have been, if only things had been different, and helped it instead become something truly special.

For LeHeup, the person who arguably put the most into the project, it remains one of the comics he’s most proud to have been involved with. He loved working with a “diverse cast of creators whose work” he reveres, even if still feels like an unlikely success to him.

“It does feel like an anomaly that shouldn’t have existed, and yet does. I think that there’s a specialness to that, a novelty to that,” LeHeup said. “When it works, it’s like magic.”

“In that way, (Strange Tales) felt like a force for good.”

Marvel could basically power an entire volume of this title just on whether or not Spider-Man or Daredevil characters lived.↩

Emphasis on “can.” What If…? had its fair share of tough reads.↩

Like Bizarro Comics and Wednesday Comics over at DC.↩

That previous trio had done basically zero work for the Big Two at this point, so it was quite the change. Also, unlike most of his work at Marvel, Hickman provided writing and art for his entry.↩

Quick note: Sitterson declined discussing this project with me, as he preferred to focus on his written work these days.↩

Brevoort, Marvel’s Executive Editor and Senior Vice President of Publishing.↩

Barber noted that editor Ralph Macchio was always against that idea in particular, as he believed within any character could be someone great. He used Bullseye as his main example, because in the hands of some, the character was a goofball, but when Frank Miller worked with him, the character became a legend.↩

Important note: this was right before the first Iron Man movie was released.↩

At this point, Lemire fit that classification, I swear!↩

Talk about a What If…? situation. I’d love to have seen all of their takes on Marvel creations, even if someone like Mazzucchelli obviously did plenty of notable work with the publisher.↩

I should note: even Rugg spoke highly of the project, noting that Marvel paid either way and that it was “a lot of fun!”↩

The best joke in the whole comic is one about Cable trying to find an access card in one of his millions of pouches, with his team-up partner Spider-Man being overwhelmed by baddies behind him. Maybury intended this as a shout out to a great source of nostalgia for him, as he told me he “loved Liefeld’s Marvel era!”↩

It’s also home to a little Easter Egg, as Dalrymple made a mistake in Photoshop on the bottom panel of the first page, and even though he noted it to Marvel, this halo above the existing thought bubble was never corrected. It’s still there on Marvel Unlimited to this day.↩

Quick note: Kate Beaton’s version of Kraven from the series – a character originally suggested to her by writer Ryan North – ended up being the inspiration for the character in The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl…which was written by Ryan North. I love the circular nature of that story.↩