The Quiet Giant: On Comics and Libraries, and What’s Driving the Growth of this Potent Combination

I’m someone who makes a lot of lists of my favorite things, whether you’re talking TV shows, movies, food, Harry Potter characters, or really anything. It’s something I do, and it’s not even intentional. My brain just categorizes inputs naturally, and that’s the way it is.

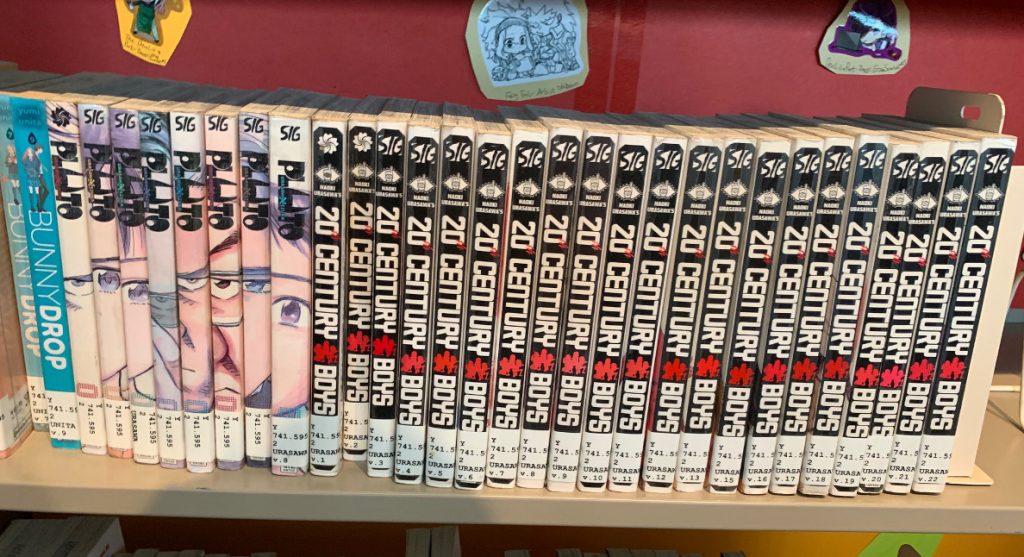

Comics are something I’m perpetually updating my lists on, of course. It can be difficult to break into the upper echelons because I’ve read so many and I’ve been reading them for so long, but still, some make it in there. Case in point: Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys, a 22 tankōbon volume series about nice, simple things like friendship and preventing the apocalypse. I read it for the first time around 2013 or 2014, and it immediately shot to the top of my list: it’s 1b on my favorite comics ever list, at least for now. 1

And the incredible thing is I probably would have never read it if it weren’t for my local library.

You see, even as a long-time comic reader, manga can be intimidating. Some titles are so massive I can’t even imagine how to start with them. 2 20th Century Boys isn’t even particularly long, all things considered. But still, 22 volumes is a commitment, and one made easier by my local library. After I enjoyed but was still uncertain about the title’s first two volumes, I visited Anchorage, Alaska’s Loussac Library – which has been my home library for effectively my entire life – and found that they carried seemingly every volume of this series. Just like that, I’d discovered one of my favorite comics ever. And thanks to the library, it didn’t cost me over $300 like it would have if I bought it. 3 Instead, it just cost me the time it took to sign up for a library card years before.

I’ve discovered many comics I love through the Anchorage Public Library’s incredible comic collection, as they have an immense assortment of manga, hugely popular titles like Saga and The Walking Dead, comics from the wider European continent like Blacksad and The Incal, indie fare like Duncan the Wonder Dog and Giant Days, young readers comics, and all the superhero comics one could ever want. It’s a cornucopia of all of the best comics and graphic novels in the world, offering readers both new and old a tasting platter of everything the medium has to offer.

You can find these kinds of collections at libraries basically anywhere, as these brilliant purveyors of literature and community have long advocated for the medium. Brittany Netherton, the head of Knowledge and Learning Services at Darien Library in Darien, Connecticut, told me that the love story between comics and libraries is nothing new, citing two key examples as proof. Randall W. Scott’s Comics Librarianship: A Handbook published in 1990 and Will Eisner himself touted the “acceptance and acknowledgement” of comics by public librarians as “the most significant evidence of comics’ arrival” back in 2003 within his introduction to Stephen Weiner’s The Rise of the Graphic Novel: Faster Than a Speeding Bullet, and those two highlight the longevity of this connection. Comics and libraries are an essential partnership, and have been for some time.

Even with that in mind, the past 15 years have been a watershed period for that relationship, as the comic medium and the graphic novel format in particular have become key elements of library comic collections around the country. As Loida Garcia-Febo, the American Library Association’s immediately previous president, shared with me, “in most cases you will find a huge movement in comics and graphic novel collections” in libraries not because they are what librarians think the community needs, but because communities are demanding these works. At the core of the idea of libraries is community service, and Garcia-Febo views graphic novels as vital to achieving success in that regard.

Talking to other librarians from around the country, they’ve seen interest skyrocket over that period, and it’s seemingly at a high point today. Rachel Ayers, a collection development librarian at Anchorage Public Library in Alaska, described graphic novels for grade school readers as “like a black hole.” 4 They’re just constantly checked out.

“I can’t buy enough for that age range,” Ayers added.

It’s not just young readers. Ayers said they see “great circulation in the young adult and adult collections as well.” 5 Franco Vitella, an Adult and Teen Services Librarian from Toledo Lucas County Public Library in Ohio, agreed, saying, “more and more library patrons are becoming interested in comics across all age groups.”

In some ways, this makes libraries the oft forgotten giant of the comics industry. They rarely make it into the broader comics conversation, especially relative to other channels like the direct or book markets. But all of the interplay between libraries and comics adds up in a substantial way. Amie Wright, the President of the American Library Association’s Graphic Novels and Comics Round Table, told me that just getting on a reading list for a state library system or on a school curriculum list can lead to a comic being picked up in “hundreds of thousands of numbers,” keeping titles in print longer and turning them into huge successes in the process.

That’s a significant impact, and one that has only been growing. But what’s driving that growth, and what can be done to continue to foster the potent relationship between comics and libraries that is making and has made the comic fans of yesterday, today and tomorrow? That’s what we’re going to try and answer with insight from some of the people at the intersection of this phenomenon.

There are a number of recent milestones to point to as drivers of interest in comics at libraries. Netherton listed a slew off to me, including graphic novels both being nominated for and winning awards, being added to school curriculums, 6 the massive popularity of Raina Telgemeier, and, of course, the immense success of comic book adaptations and merchandise in the larger zeitgeist.

Random House Graphic’s Publishing Director Gina Gagliano noted others, including Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese winning the Printz Award, Cece Bell’s El Deafo and Victoria Jamieson’s Roller Girl earning Newbery Honors, Telgemeier’s Drama and Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki’s This One Summer being added to the ALA’s top ten most challenged books, and more.

But at the center of everything Netherton and Gagliano mentioned is one word: legitimacy. As Gagliano emphasized to me, “all of those moments and this level of recognition have had a major impact on the state of graphic novels in libraries, raising the profile of kids graphic novels and providing legitimacy for the medium in this area.”

And that’s important. As in the wider zeitgeist, there can be a stigma connected to comics and graphic novels in libraries. Some still perceive the medium to not be “real reading,” so to speak. That’s why it helps to have these kinds of awards and commendations to say, “Actually, it is.” Wright has experienced it first hand. She was surprised by the pushback she still received from both educators and librarians.

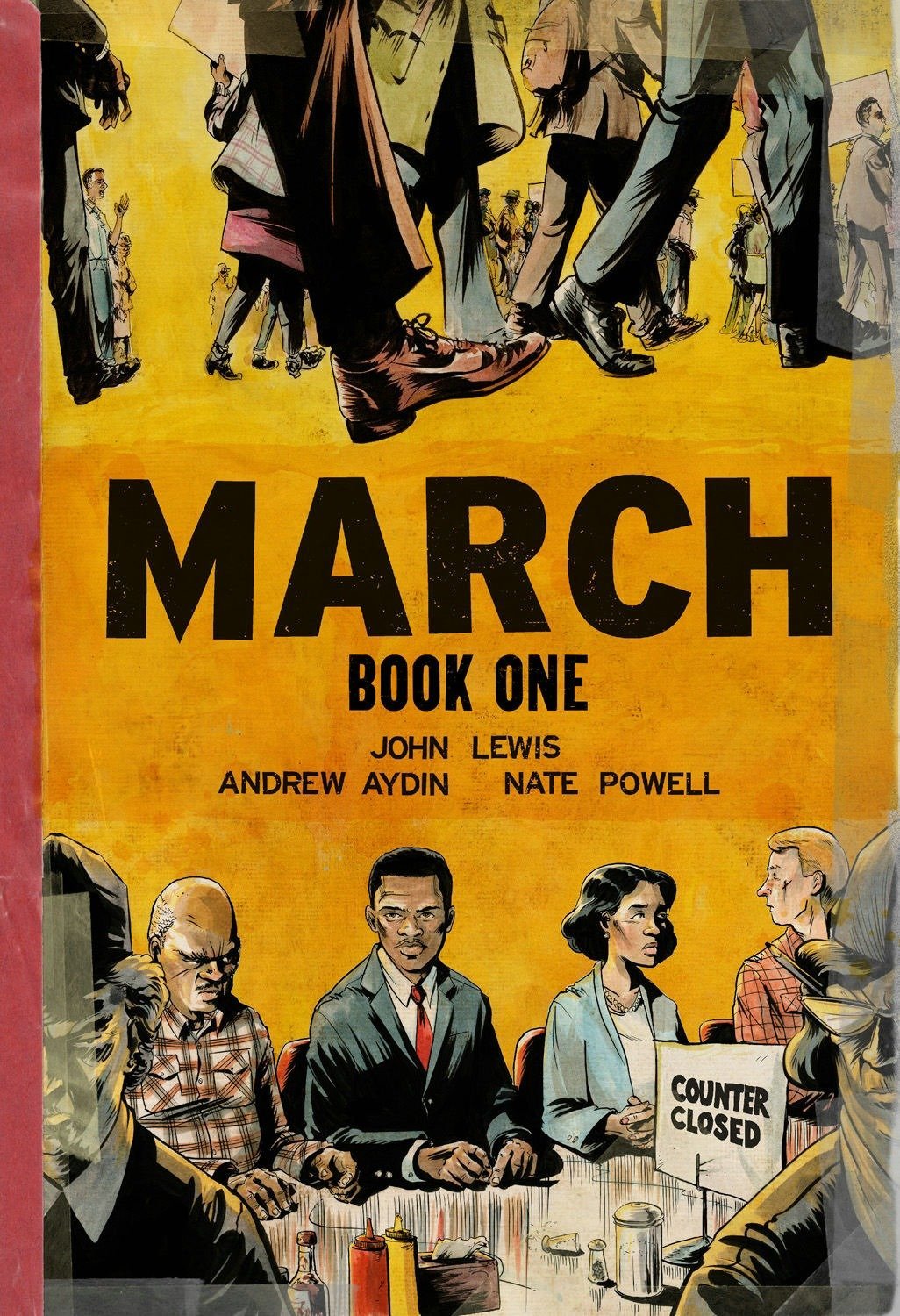

She recalled presentations she did for teachers at her previous role at the New York Public Library in which she faced resistance towards comics and graphic novels as useful tools. These educators and librarians scoffed at their viability, questioning the legitimacy of the medium in the process. She was able to point to screenshots of New York’s Common Core State Standards’ suggested use of graphic novels and even Congressman John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell’s March’s position on the state’s Social Studies curriculum as evidence to the contrary.

“They were like, ‘…oh.” afterwards, Wright said. These kinds of bona fides made a case that was difficult to ignore.

The rise in this perceived legitimacy has been aided significantly by efforts from the American Library Association (ALA), a nonprofit that advocates for libraries and what they bring to the table. This organization is an extension of the broader world of librarians, who are a group of people Gagliano described as “some of the most active, passionate champions of comics and graphic novels,” and one that’s been working to move the needle for years.

ALA has aided that work by developing more avenues to support comics in specific, as the organization has provided professional development sessions at comic conventions around North America, 7 hosted webinars about different aspects of the medium, expanded its comics and graphic novels section at its annual conference, 8 and more. But there’s one recent change at ALA that arguably stands above the rest.

“I think the most significant thing that has resulted from the past decade of efforts from librarians is that we now have a comics-focused professional group, the Graphic Novels and Comics Round Table that is part of the American Librarian Association,” Vitella said. “Everybody there is doing an amazing job promoting how libraries can embrace comics.

“Having this group really solidifies the position that having comics in libraries is important and that they’re here to stay.”

That organization 9 is something Wright – its President – views as “an umbrella group to bring together a lot of the work that has already been happening and to bring a lot of professional legitimacy.”

Wright specifically noted that many librarians wanted to attend the professional development sessions that had been developed for conventions like New York Comic Con and Toronto Comic Arts Festival but were met with resistance from the principals or administrators at their respective libraries. Members of library management didn’t see these sessions as important because they were about comics. Wright views the GNCRT as a path to making comics something these gatekeepers can’t ignore.

“I think having that official recognition in our professional guild goes a long way to that legitimacy, where we can say, ‘No, this is actually a part of library service,’” Wright said.

There are many other Round Tables at ALA, but the Graphic Novel and Comics one was the first addition in five years when it was launched in 2018. It only made sense to Garcia-Febo that graphic novels and comics would get their own one, as these Round Tables are designed to reflect what the communities of libraries are interested in.

“Graphic novels and comics are an important part of what we’re doing,” she said.

The GNCRT was described by Garcia-Febo as “instrumental” in coordinating the larger efforts of ALA on the graphic novel and comics front, fostering an increasing amount of the aforementioned professional days, working with Garcia-Febo and industry professionals on a webinar focused on diversity in comics, and bridging the gap between the organization and the people who make the comics these librarians are so passionate about. She said the work this group is doing is a real “labor of love,” as well as being “vital” in equipping librarians with what they need to provide for their communities. After all, the diverse populations libraries serve require an equally varied mix of creators and publishers. That’s a real focus for the Graphic Novels and Comics Round Table, according to ALA’s former President.

That last point is also a key to everything that’s driving the flourishing relationship between comics and libraries. Diversity – in creators, subject matter, target markets, formats, delivery methods, everything – has been essential to this partnership becoming what it is. A wider variety of comic stories helps libraries better serve everyone in the communities they represent. And when communities are better served, that leads to more interest in the medium within them, which generates more requests and engagement with the library. One begets the other, and so on, and so forth. Garcia-Febo shared that due to this, “We are attracting readers that we perhaps weren’t attracting readers before,” which makes this relationship a win win for everyone involved.

Vitella agrees, saying that “diversity in comics on all levels has everything to do with the growing interest in the medium,” especially since comics once meant just superheroes to the average person with little else to select from. Now? It’s much more than that. This doesn’t just give readers an in, but more paths to choose from once they’ve become interested in the medium.

“I think there are clear lines connecting diversity in comics to generating further interest in the medium, especially in younger people,” Vitella said. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve encountered a high school student whose first comic is Persepolis or Maus, which they’ve had to read for school, and that creates a spark that leads them to Paper Girls or Ms. Marvel or whatever else that might interest them.”

Unsurprisingly, this means libraries see a wide mix of success stories amongst the comics that connect with readers. Of course manga and expected names like Telgemeier, Knisley and Kibuishi were cited as well as a mix of superhero titles, 10 but there were some unexpected books in the mix as well. Artier, more highbrow fare from Fantagraphics and Drawn & Quarterly play well at Vitella’s library, as does Tintin of all titles. 11

They’re seeing that on the publisher side as well. Chloe Ramos-Peterson is the Library Market Sales Representative at Image Comics, which she describes as the person who “oversees everything Image does involving libraries.” She came from a background in libraries, and suggested there “isn’t any genre out there that isn’t popular with libraries and librarians,” with Image’s own biggest books on the library front existing as perfect examples of that.

Sure, the usual suspects like Monstress, Saga, The Walking Dead and the aforementioned Paper Girls are big hits, as they are in the direct and book markets. But as Ramos-Peterson shared, “The cool thing about libraries is that you also see big success in genres like memoir and biography, non-fiction, #OwnVoices, romance, and graphic medicine.”

“These are genres that often struggle to find wide distribution and success through some direct and book market outlets and yet they thrive in libraries with titles like Age of Bronze, Bingo Love, Black History in its Own Words, Moonstruck, Norroway, Nothing Lasts Forever, and Sleepless” leading the way, Ramos-Peterson told me.

The books Ramos-Peterson cited underline another important facet of diversity as well. The diversification of creators and characters is huge because it allows readers of all varieties to find themselves represented on the page, but the variety of genres comics delivers these days – like the wide mix showcased in the selects Ramos-Peterson mentioned – make it more likely readers will find something for them. As Ayers mentioned to me, “Comics isn’t just about one thing.”

“If there’s a type of story you like, you can find it in graphic format.”

This helps a wide variety of audiences, but Netherton highlighted two underrated ones. She “actively purchase(s) graphic novel adaptations of classics so they can be used by reluctant readers for required summer reading,” and that graphic novels “can also be useful for English language learners.” The combination of words and images can be appealing to both of those audiences, as the visual nature of graphic novels help readers better understand elements as simple as narrative or as complex as the world of medicine. 12

Of course, comics are not the end all be all in terms of tools for those audiences. But as Vitella shared with me, “as far as literacy tools go, librarians just want people to be reading, and comics are just another thing we have in the toolbox.”

At the center of the burgeoning relationship between comics and libraries, though, has been the massive influx of graphic novels for younger readers. For a long time, this audience was strangely underserved by comics. But a real milestone for comics in libraries took place in 2005 when Scholastic Graphix and First Second both came into existence, creating two of the biggest and best publishers of comics for younger readers. Gagliano was there early on at First Second and saw the growth herself, both of kids comics and how successful they were in libraries. It’s been a reciprocal relationship in her eyes.

“One of the major things that’s changed kids comics overall in the past decade is that more authors are creating kids comics, and more publishers, especially more book publishers, are publishing them!” Gagliano told me. “More comics existing, more different kinds of comics existing, and existing in a way that makes them easily accessible to libraries, is a major industry change.”

“The fact of more comics existing also means that more kids and teens are reading them; and that’s a major factor for libraries too,” she added. “Librarians are very engaged with what kids and teens want to read; and finding ways to support that – which leads to more kids and YA comics in libraries!”

All of this is why libraries have been and will be immensely important for Random House Graphic as Gagliano continues to build this new young readers graphic novel imprint with her team at RHG and at Random House Children’s Books, 13 as she called libraries “an essential part of the book landscape.”

“They are for any children’s publisher, and that’s especially the case with areas in publishing that are still growing, like graphic novels,” Gagliano said. “Having librarians championing the books you publish to kids and teens and parents continually gets these books in front of new readers.”

While each librarian I spoke to noted how diverse the comic and graphic novel audience is in libraries, it was largely agreed upon that kids comics are the biggest game in town. Vitella shared an anecdote about his library, saying how early in the summer they had a nice full selection of comics, but basically as soon as the school year ended, the library was cleared out.

“I think that bodes well for the future of comics,” Vitella said. “Those kids are growing up with comics, which makes me think they’ll continue to read them as they get older.”

One other monster in libraries is, of course, manga. It has been a huge driver for a long time now in the book market in particular. Libraries are no different. It’s particularly huge for teens and young adults, as Ayers said, “I cannot get those young patrons enough manga.” She added about a dozen new titles recently. They’re always checked out, effectively.

This all matches what Kevin Hamric, the Senior Director of Publishing Sales at VIZ Media – the largest manga publisher in America – has found. Manga does well across the board in all sales channels but their manga for younger audiences “does particularly well in libraries,” which they like to see as they hope to “gain a reader for life” in the process.

Hamric described libraries as always being “an important channel for VIZ,” and that it continues to grow every year. A big part of that stems from manga finding maybe its biggest advocates in librarians. Hamric said they were ahead of the curve in understanding the impact these comics could have on audience.

“Librarians were instrumental in helping bring manga, comics, and graphic novels from ‘behind the curtain’ and making them more widely accepted,” Hamric said.

They hope to continue to grow this channel, viewing it as “an essential part” of their efforts and growth plans.

“Getting manga from libraries is an easy entry into the category as a whole or into a new series and it gives readers a wide selection of stories, genres, and incredible art,” Hamric shared.

That final point Hamric made is crucial to the value of libraries, and it’s what makes them so attractive to such a diverse audience of potential comic readers. As Ramos-Peterson told me, “Libraries are important channels in the comics world because for an increasingly large percentage of the population, they are the primary and in some cases the only way people can access comics.”

That’s immensely valuable, and something I noted early on in my experience with 20th Century Boys. Comics can be intimidating to get into for a number of reasons, not the least of which is price. It’s like Ayers told me: “Comics are expensive. So people are delighted to find them in the library.”

Will Hunting wasn’t wrong about libraries. You really can get an equivalent experience to what others have for just a small sum of late fees. For comic fans, that’s doubly true. Sticker shock can be a huge roadblock for readers looking to get into comics, but many potential readers around the world are just a library card away from accessing a lifetime’s worth of comics and graphic novels. That’s at the heart of how libraries and comics have become such a good match, Gagliano shared.

“One of the biggest challenges for graphic novels – and for books in general – is access: how do people get books to read? How do they afford books to read? How do they know what books to read?” Gagliano said. “Libraries and librarians are the answer to all those questions – and with them championing graphic novels and making a space for them in their world, more kids and teens and parents get to discover how amazing they are.”

And it extends beyond the library. Hoopla, a media streaming platform powered by your library card, can give you access to a huge mix of comics without ever needing to leave your home. Vitella described Hoopla as “HUGE” in his library, with usage growing each month, especially amongst young readers.

“Last year I did a talk for students at a local school about the library’s digital resources and as soon as I mentioned Hoopla and comics kids started registering for the service right from laptops at their desks,” Vitella said. “And when I table at a local comics shop for Free Comic Book Day, most of the people I speak with are already using Hoopla.”

Access is crucial to the relationship between comics and libraries, as priced out audiences get a legal and effective way to read the comics they’re dying to enjoy while having the world’s greatest discoverability tool available to them: a good librarian. That can be essential to readers of all varieties, and all of this combined has helped foster the growth comics have seen in the library channel.

Needless to say, there are a lot of benefits and opportunities at the intersection of comics and libraries. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t more that can be done to further this relationship. Wright said there are more roadblocks than she expected in getting graphic novels adopted amongst some libraries – even within library management, which she believes needs to diversify if they are really meant to be community institutions – but also that things are changing. She’s doing what she can to continue removing those barriers during her year term as the President of the ALA’s Graphic Novels and Comics Round Table. That’s why a big part of her focus is on membership.

“I want to continue to grow our members and ensure that people feel that there’s a place at the table for them. You don’t have to be in librarianship,” Wright said, even citing one of my fellow comics journalists as someone from the comics community who is very active with the GNCRT.

“Chris Arrant from Newsarama has been one of our strongest advocates, and we have a campaign that Chris put together which is called Creators Get Carded, and it’s creators posing with their library cards, all to emphasize this mutual beneficial relationship.”

For Wright, it’s all about “ensuring people understand that there’s a seat at the table for them if they started reading comics 20 years ago or yesterday.” Gatekeeping is a long-standing problem in comics, and Wright wants that to be a thing of the past, particularly when it comes to libraries.

She wants to continue to build their base of supporters and develop “really practical tools for people so that no matter where they are on this journey, there is something for them.” That’s something she and one of the GNCRT’s members-at-large – Matthew Murray – have been pushing, as they look to build those tools via the Round Table’s Awards and Reading Lists committee and its Resources and Toolkits Committee. Those kinds of tools make the barrier to entry for new readers that much less, which can be hugely valuable.

Each of the librarians I spoke to had their own wish lists of things they’d like to see from the organizations that support them and the publishers they work with. Vitella had a particularly robust idea, saying he’d like a readers’ advisory tool – which he described as “a fancy way” of saying a recommendation tool that helps librarians find similar titles to ones readers already like – specifically for comics, as it would greatly aid in discoverability of new comics both for librarians and readers.

Netherton, Ayers and Wright all emphasized a continued focus on diversity in all meanings of that word. Netherton specifically shared she’d like to “see more diversity in print” while “getting more women and people of color on panels at cons,” and that’s huge, as it helps diverse readers feel more welcome by seeing themselves on the page and stage. Wright mentioned how important it is for libraries to also consider the diversity of which publishers they’re buying from, noting that she sees “a lot of schools only buying from Scholastic,” which is a tough way to speak to a wide variety of readers. Scholastic is certainly worth buying from, but a mix helps better serve a broader audience.

Format was an important topic for Ayers and Vitella, as the latter just wants publishers to get their single issue titles to the trade format faster, 14 while the former finds that “one of the biggest problems” her library has with comics “is the durability at the price point.”

“It’s a delicate format, and when you’re talking about a title that is going to circulate hundreds of times, it needs to be able to stand up to some rough use. Offering the hardcovers helps, but then of course the price shoots up,” Ayers said. “It’s something that I’ve tried to find a balance on a lot over the years, and I do think it’s improved in the last five years or so, but it’s still about finding that balance between buying cheaper formats, and more durable formats, especially with the materials for younger readers.”

Speaking of younger readers, Vitella suggested that there’s one audience that’s being lost in the mix to a degree, and it’s one that’s worth paying attention to.

“I do think there is a gap in the ‘tween’ or ‘middle grade’ area of publishing and we need more books for this audience,” he shared. “There are a ton of great comics for kids, and plenty of comics for older teens/adults, but finding something for a 10-14 year old can sometimes be a challenge.”

These are all reasonable requests, and each of the people from the publisher side I spoke to were eager to do what they can. Ramos-Peterson said that “the most important part of my job is listening and learning,” and that it’s her job at Image to “make sure we respond to anything they feel is lacking or that they could use more of.”

Libraries are a key focus for Image, and Ramos-Peterson noted that they’re always “trying to think of new ways to be involved and new things (they) can offer to help people read (their) books and use them in programming.” The creator-owned giant has made the ALA Annual Conference an increasingly significant part of their focus, as it gives them quality face time with librarians.

Hamric views that event in a similar light, and it’s something VIZ has long been a part of and will continue to build on. They’re doing what they can to expand and fine tune their relationship with librarians outside of that, with their librarian-specific monthly newsletter going through a “reformatting in the near future” to improve its effectiveness.

“We are constantly looking at what we can produce for librarians to help them with our manga and the category as a whole,” Hamric said.

Gagliano is of course on the same wavelength as both of them. She is – in my estimation – just about the single biggest advocate of comics and librarians you can find. With Random House Graphic’s first books debuting next year, Gagliano and her team at RHG and Random House Children’s Books are doing everything they can to chart a path with librarians. They attend conferences aimed at teachers and librarians and constantly communicate with these professionals to ensure their books are on the radar of libraries and that these institutions are armed with all of the resources they need.

While those are only three publishers and a handful of librarians, it’s clear there is more to do, and that at least in some parts of the comic industry the work is being done to continue to build an even more positive collaboration going forward.

The relationship between comics and libraries will continue to grow, if only because it’s in the best interest of everyone if it does. It’s incredibly beneficial for both sides. Consider what Wright said earlier in this piece about the impact libraries can have on graphic novel orders if they just make a reading list for a state library system or an educational curriculum and then think about this from the other side of the equation.

“A lot of library systems report them as having if not the highest then one of the highest return on investments. Whether you’re talking about public libraries or school library that is really important,” Wright said about graphic novels. “These really circulate. Why wouldn’t we buy stuff that circulates?”

The good news is that’s likely to continue, if it doesn’t accelerate even. As the librarians I spoke to shared, a graphic novel collection isn’t just a good thing to have, but an essential aspect of a healthy library collection.

“The foundation of good collection development is maintaining items for all members of the community,” Netherton said. “So comics are just as important to meet that goal as biographies, poetry, travel books, fiction, etc.”

“When you look at the statistics, especially among young or reluctant readers, there’s no question about it. This is a beloved format, and a jumping off point to other kinds of reading,” Ayers told me.

“A healthy graphic novel collection is an absolute necessity for contemporary public libraries,” Vitella added. “Readers want comics, and our job as librarians to provide popular materials that our patrons want.”

Readers want more comics. Librarians want more comics. Publishers are presumably more than happy to give them what they want. All of this will ensure a healthy relationship between the medium and your friendly neighborhood libraries going forward.

But there’s one other thing that’s worth remembering, too, and that’s that the comic industry is an ecosystem. And it’s one libraries are a huge part of. Readers discovering comics through libraries could lead to benefits for comic shops, bookstores, publishers, creators, and really anyone who works within comics in any capacity. We often talk about the struggle comics can have at generating new readers, and libraries may very well be the greatest tool we have in that regard.

As Gagliano told me, “there’s a library in every city in America. And the books there are free.” That’s a powerful point, and it’s also why there are few better ways new and potential readers can discover the world of comics than through the libraries of the world. Because of that, a strong relationship between comics and libraries helps everyone do a little bit better today and tomorrow, building a better future for the medium as a whole in the process.

Thanks for reading this week’s longform on SKTCHD. If you enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more longforms looking into the world of comics, interviews, regular columns, and a whole lot more. Learn more about SKTCHD subscriptions here. Header is from Anchorage’s Loussac Library.

Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s Preacher is 1a, in case you were wondering.↩

This is understandably how many feel about superhero comics as well.↩

I also later bought the whole series. Like I said, I enjoyed it.↩

To quote APL’s Youth Services Coordinator, she said.↩

She said that this can be hard to tell by looking at their shelves because “the majority of the youth and young adult collections are always checked out.” I can confirm that. I visited last Friday and seemingly every copy of a Raina Telegemeier book in the state was checked out.↩

Netherton specifically touted Congressman John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell’s esteemed March here, as she said that title “changed the game!” in that regard.↩

Wright noted that she’s been to 50 conventions over the past few years, many of which were to aid or research these kinds of sessions.↩

Which, I should mention, is an event the publishers I spoke to view as essential for making inroads with librarians.↩

Which I’ll mostly call the GNCRT from here on out.↩

Fittingly, the more diverse superhero titles tend to perform better, namely the aforementioned Ms. Marvel, Squirrel Girl and Miles Morales related comics. And Batman. Because he’s Batman.↩

Vitella even emphasized the surprising fit of Hergé’s famed creation, as after he mentioned Tintin, he followed that up with a parenthetical saying, “yes, Tintin.↩

Graphic medicine was a growing segment of the graphic novel world that was repeatedly touted by almost everyone I spoke to, and it’s a section of comics I had previously been largely unaware of.↩

That’s Random House Graphic’s parent company, which Gagliano described as having “a fantastic School & Library marketing team which is dedicated to reaching and supporting this market.”↩

Which I wholeheartedly agree with.↩