The Story of Comic Twart and the Power of Finding Your Community

When I was growing up as a fan of comics, it was easy for me to romanticize the idea of being a comic creator. As someone who fantasized about drawing comics for a living, I would often noodle in a sketchbook as a kid and think to myself, “Wow, I can’t even imagine what it would be like to be paid to do this!” It seemed like the best job in the world. I mean, what could be better than bringing your own ideas to life in an actual comic book? “Nothing,” I’d think to myself, before I’d get back to my 300th attempt at perfecting the look of Impulse.

I long ago moved past the idea of making comics myself – turns out being bad at drawing is not an ideal place to start as an artist – but as someone who writes and podcasts about them, I’ve learned a lot about the lives of the people who create them. And you know what? It turns out there’s a lot more to it than having a good time drawing your favorite superheroes!

While there are plenty of positives and many of the creators I’ve spoken to wouldn’t trade jobs with almost anyone, the negatives are ideas most fans don’t think of as they’re lamenting a strange face or a seemingly unfinished background in your average comic. A lot of it comes from a basic element of the job, and that’s if you want to draw comics, you have to spend a lot of time doing that. That’s not inherently a problem. Jobs often require you to spend a fair amount of time doing the thing you were hired for. It’s a rather key component. But for comic creators, it’s what that time takes from you.

Let’s use a real world example. Several years ago, I wrote a big piece looking at the life of a comic book artist, and within that, artist Declan Shalvey was featured. He shared that it would take him 17 hours to finish a single page, which would equal 340 hours for a standard 20-page comic, or just over 14 days of solid, concentrated time put into one issue. That’s a lot, but the time itself isn’t inherently bad. It’s just time.

The real problem comes from the fact that this time is typically spent in isolation, as drawing comics requires concentration and focus if you want to do your job right. That means you’re not spending time with friends, family or even co-workers, you’re not developing your skills through study or research, you’re not networking, you’re not really doing anything except drawing. There’s a mental and professional cost to that, and it’s something many struggle with for understandable reasons.

That’s why finding a community of peers is hugely important for comic book creators of all varieties, but perhaps even more so for artists. Finding people you’re compatible with gives you someone who understands what your life is like. They can help push you or think of your work in a different way. When you’re forced into the scary real world at places like comic conventions, they give you a group to lean on and hang with. They can even help you build important connections, as the success of one can benefit the community sometimes.

While there’s value in connecting with creators of all varieties – I mean, who doesn’t want to talk with the giants of your field? – finding people at the same level as you is maybe even more valuable than other relationships you can have, as it gives you common ground and a group to grow with. That’s immense, and a key weapon as creators battle the grind of the job.

One of my favorite examples of how important community can be was Comic Twart, a sketch collective forged from the fires of Twitter in 2010. It featured *takes breath* Chris Samnee, Declan Shalvey, Tom Fowler, Evan “Doc” Shaner, Ramón Pérez, Mike Hawthorne, Dan McDaid, Nathan Fairbairn, *takes another breath* Mitch Gerads, Mitch Breitweiser, Steve Bryant, Francesco Francavilla, Dave Johnson, Andy Kuhn, Dan Panosian, Ron Salas and Patrick Stiles, and the idea was simple: each week a different member would select a theme for everyone to work off of, and then they’d draw and post it onto the site.

This was before many of these big deals were grade A “Big Deals,” and for this comic fan, it was an introduction to them that formed the foundation of a lasting love of their work. It’s a moment in time from comics I’ve always been fascinated by, if only because it’s an impossible assemblage of talent when you look at it now. 1 And today, we’re going to look back at the story of Comic Twart with perspective from many of its original members, and how this idea that started as a lark ended up being not just something that was fun, but an important community to those who were involved.

As is often the case with moments in time from nearly a decade ago, how Comic Twart came together very much depends on who you ask. Specific details are uncertain, but largely, the core story is roughly all the same. It was a bunch of artists yakking on Twitter about comics and art that eventually became something more.

“My memory of the whole thing was Comic Twart just started because there were a bunch of artists on Twitter who had time on their hands and were doing warm up sketches and just drawing basically,” writer and colorist Nathan Fairbairn (Lake of Fire, Jimmy Olsen) shared. “Most of them didn’t really have too much paying work, so they had time.”

“We would all talk about artists whose work we loved, and compliment each other’s stuff, only for the artist in question to get all insecure and shy away from any compliments, y’know, the usual stuff,” Declan Shalvey (Injection) told me.

“The Twart started on Twitter, with – if I remember correctly – Declan (Shalvey), (Mitch) Gerads, (Mitch) Breitweiser, Chris (Samnee), Tom (Fowler), Ron (Salas), Francesco (Francavilla), and myself all talking about using the same character for a warm-up sketch that day,” Evan “Doc” Shaner (Batman Beyond) said.

“A lot of us had been posting fan art, and one of us suggested we all do the same character. I remember saying Thor was a character that I probably couldn’t draw and Fowler chastised me for it,” Shalvey added.

“My recollection is that Evan and Declan in particular started having a very loud public conversation about the things they can’t draw. Specifically characters they don’t like drawing because they don’t think they can draw them,” Tom Fowler (Doom Patrol) said. “And then that kind of degraded into ‘I’m bad at drawing wings’ or this that or another thing. Specifically I remember it being Thor but it may have been something else. And I just waded in in my big brotherly capacity to say, ‘Pro tip: maybe don’t discuss the things you can’t draw in a public space when you’re looking for work. (laughs)

“And they were both like, ‘Oh shit!’”

“I was probably trying to prove I could actually do it, and knowing the other guys were going to be doing the same character definitely made me want to up my game,” Shalvey shared.

“This became a conversation over a course of a week where a bunch of us contributed drawings of Thor on Twitter,” Fowler said.

“Then I think a few more guys posted as well and we kinda joked about what we should all draw the next day,” Chris Samnee (Black Widow) said. “Then it honestly kind of took on a life of it’s own.”

Its origins were completely organic, as it was basically a slew of artists having fun drawing the same thing and sharing it on Twitter. As Fairbairn told me, it quickly garnered a fair amount of traction on the social media platform, with retweets and favorites flying around at an incredible rate. 2 It found the crew moving the conversation to email 3 to ask each other whether or not this should become a bigger thing. In short, should they make a sketch blog together?

This was before Twitter had really figured out specifics of sharing images while Instagram didn’t even launch until after Comic Twart, as Samnee noted to me. Having a website or at the very least a blog was essential to an artist’s discoverability in comics, and the idea of this whole crew putting together a sketch blog would certainly make it easier for people to find their art relative to Twitter and its ephemeral nature at the time. 4

The idea appealed to each person I spoke to for different reasons. For Shalvey, who was a newer creator and the one of the two people in the group that lived outside of North America, 5 he thought it’d be wise for him to partner up with American artists as to improve his own visibility. For Ramon Pérez (Jim Henson’s Tale of Sand), an artist who had participated in these kinds of collectives before, he recognized the value of the group and how there really was power in numbers in terms of raising your profile. Dan McDaid (The Fearsome Doctor Fang) was excited at the idea of having a rotating theme, as it forced him to draw things that were outside of his comfort zone.

But really, when it came down to it, everyone looked at it as a chance to learn from some highly talented peers and, perhaps most importantly, as an opportunity to have some fun with their art outside of the grind of the working artist life alongside some pals.

“Drawing comics all day can be pretty isolating and it’s nice to have a group of friends that do the same thing,” Samnee shared. “It was really just about the fun of seeing how all these awesome artists interpreted the same character or theme.”

Once they sorted the broader idea out over email, it was onto formalizing the process and putting it all together. As noted earlier, the whole concept was rather simple. Each Monday, a different artist would select a theme – they rotated in alphabetical order by last name – and each person would draw a piece for it, if they had time. There was one last thing they needed, though: a name.

“I will take credit for the name though,” Shalvey told me. “I definitely came up with that.”

“There was a lot of discussion on what we should call it. Comic Twitter Art? Then Twart made us all kind of laugh,” Fairbairn shared, before adding with a laugh, “It sounded kind of dirty.”

“It was equal parts funny and disgusting, and if I recall correctly, Laura loved it, and that’s when she went ahead and created the blog site,” Shalvey added.

The Laura that Shalvey referred to is Samnee’s wife. Laura Samnee set up the original blog – “Laura has always been my behind the scenes help and she was the one who would put things on my blog because she is much more tech savvy than I am,” (Chris) Samnee told me – and from there, Mitch Gerads (Mister Miracle) put the logo together. With that, they had a formalized idea, a name, a logo and a site. It was go time.

The original lineup of contributors was effectively the final one, as they decided to keep it to just that core group – save for Dave Johnson being added after a year, as they felt they should add someone to the lineup to celebrate, and who better than one of the best artists in comics? – despite a lot of outside interest from artists wanting to join.

However, there is one artist from the collective that might stand out to you, and that’s Fairbairn. After all, at the time he was only working as a colorist and since has just added the title of “writer” to his business card. He wasn’t a line artist like the rest of Comic Twart’s members. Even Fairbairn recognized this, as he alluded to his atypical fit in his Zorro piece the first week of the site, saying, “I’m not sure what I’m doing here, honestly — a colorist in the midst of you graphite and ink monsters. Maybe I’m like the average dude who’s put in a photo of the world’s tallest man just for scale.”

The truth is, line art was always an interest for Fairbairn. He even had a comic strip in college that he described as “fucking terrible” and something he hopes “no one ever finds.” 6 But as he was considering a career in comics, Fairbairn reflected upon his abilities and decided that while it would take him at least five years to get to a point where he could make it as a line artist, “I bet I could get in as a colorist or an inker way faster than that.” He went the colorist route, but the interest in line art was always there. So when Samnee asked him to join, he did just that.

“I was super flattered. I was like, ‘Really…I can’t really draw. Not like you guys can draw.’ (Samnee) was like, ‘Aw, it’s fine. It’s just a sketch blog.,’” Fairbairn told me. “And by day one, Fowler is doing finished gouache paintings.

“I’m like, ‘Fuck you, Fowler.’ (laughs)”

Fowler touted Fairbairn’s abilities to me, though, while also underlining the other plusses he brought to the table. For one, while Laura Samnee started the site, Fowler shared that “Everything about that site that looks usable and good and pretty…that is 100% Nathan.” Fairbairn spent time ensuring the site flowed nicely and that the art was as discoverable as possible for visitors. But on top of that, there was the obvious benefit.

“In a weird way, it also meant we had an in-house colorist,” Fowler said of Fairbairn, who, alongside Comic Twart’s other unofficial in-house colorist in Jordie Bellaire, would often color pieces the others did.

“For me, coloring other guys things is more a way to deal with my own sense of inadequacy. I felt like my drawings were shit, but I was a good colorist, so I could color someone else’s drawing to show I had something to add to this platform,” Fairbairn added. “That was really the only reason I was doing it. I felt I had to make up for my shortcomings as an artist by helping out with my color work.

“And it just made sense to have it. It made the blog look a little better.”

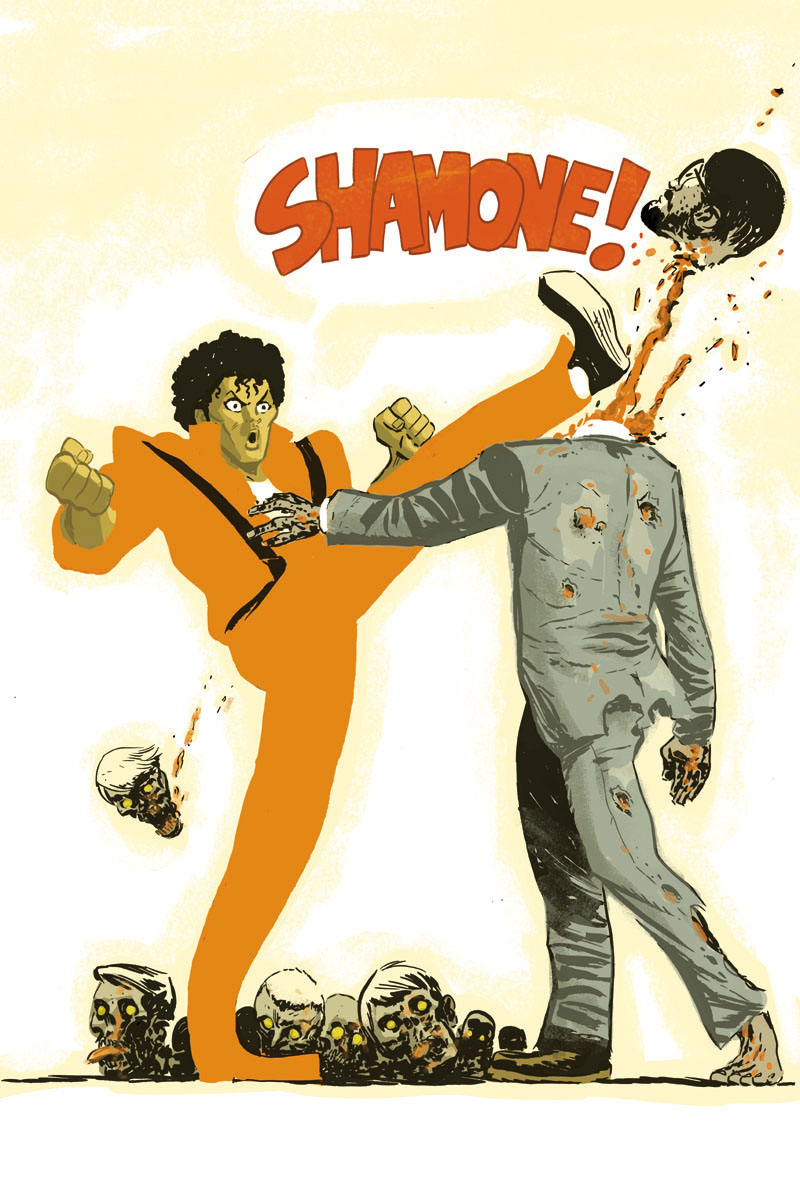

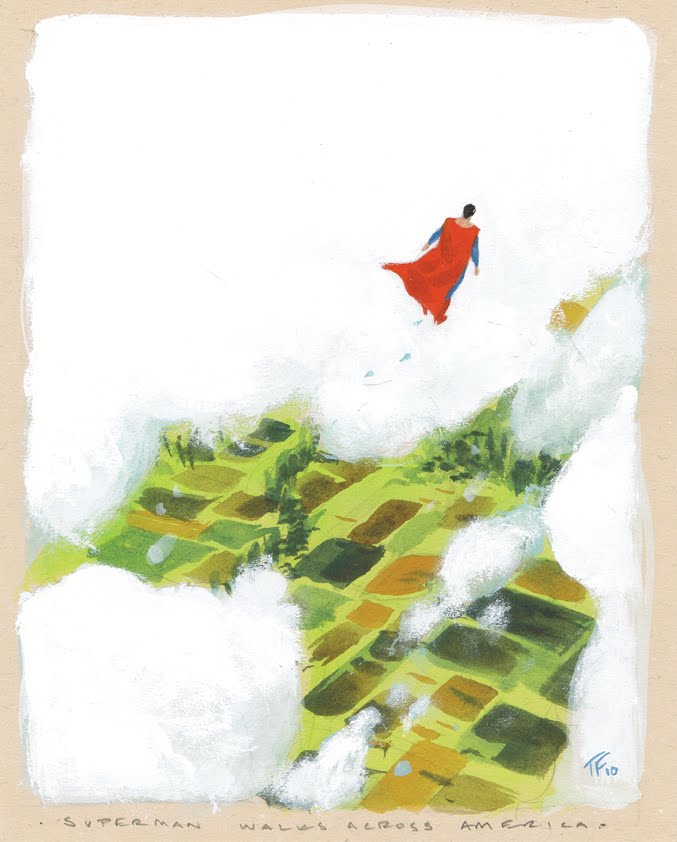

As much as I love Fairbairn’s colors, 7 with the lineup they had put together on Comic Twart, it was pretty hard for the site to look anything short of amazing all of the time. When it first launched, Twart was a site I visited at least weekly, and it was where I first discovered – and learned to love! – the work of many of its featured players. Each theme provided a deluge of incredible art, whether it was through mind-blowing renditions like McDaid’s version of Michael Jackson’s Thriller or Gerads’ Captain America or unique takes on concepts like Samnee’s Superman concept or when Mike Hawthorne (Superior Spider-Man) took on Animal Man. I was running a weekly art column over at Multiversity Comics at the time, and I remember Twart made my life considerably easier. Basically all I would have to do was cruise their site and my job would be done!

It wasn’t just me that noticed this. Other sites trolled the site regularly for content, and fans, editors, publishers and writers were equally agog whenever a new theme was announced. “What would these artists come up with next?” we all wondered.

“They were watching. The people at upper management at Marvel and DC were aware of the blog and following it,” Fairbairn told me. “Kurt Busiek was a big fan right from the first day. It was kind of surprising.”

The funny thing about Comic Twart was while its original idea came from Twitter which then led to a website being launched, it seemed like it was the site and its content being shared back to that social network that helped it become what it was. I remember it feeling like Twart content was everywhere at the time, with each theme being a viral bomb of superlatives just waiting to be set off on Twitter.

There were a number of reasons it went as well as it did, per the people I talked to. Fairbairn underlined how, for the most part, the people involved were near the beginning of their careers, which meant, “they had all the passion and optimism and joy that comes with just getting into your comic book career.” He felt as if that energy was manifested in the art, as the structure they created gave each artist something to work off of and to get excited about outside of the rigors of their jobs as line artists. But it also created a challenge and a friendly level of competition, as Fowler shared.

“If you’re going to put that much energy into something, (you’re) always going to want to impress each other,” Fowler said. “And that’s kind of the thing I always loved about it. I genuinely respected everyone in that group. I really loved when I’d put something up…I loved getting responses from fans, but I really loved getting responses from the other guys.

“That was where it was at for me. It was really nice to see one of the Dans or Samnee going ‘OOOOOO!’ or losing their minds about something.”

The passion the artists had for Twart and the competitive nature it created within each of them ensured they brought it on each and every piece. But it also escalated what they put into it, as McDaid told me, and helped many of them find a new gear with their work.

“In the first week or so, I think we were all mostly doing quick sketches, little five minute jobs between actual comics work,” McDaid said. “Then Gerads or Samnee or Francavilla would come in with these mind-bending pieces of often full color art, and that would push you to try a bit harder and put a bit more work in.”

“I think seeing the high drama of Gerads’ work, the brushy fluidity of Tom Fowler’s art, and the great atmosphere of what Francavilla was doing…seeing that kind of energy and vivacity made me rethink my own approach,” he added. “How can I make a piece not just technically proficient but also eye catching and exciting? So if I look back now, I can see a bit of a growth spurt, artistically speaking. It did push me to get better and to think a little differently.”

Shaner found that trying to keep up with his peers on Twart helped him both focus and refine what he was doing. As one of the newest artists on the site – Shaner “hadn’t drawn many comic book pages” at that point – he shared that not only did he not really have a clear vision of what he wanted to do in comics, but he was uncertain as to what his art even looked like.

“Having this weekly challenge to work something up that could even come close to being at the same level as these guys was huge for me,” Shaner said. “Particularly early on, I was throwing everything at the walls to see what would stick and so much of what I do now is culled from what I learned during that first couple years.”

Hawthorne called the experience invaluable, as it helped him expand beyond the way he drew and what he drew every day in his comic work. He hoped it would work in that way, but he found that it worked even better than he had hoped for.

“I may work in comics, but I have kind of a shallow knowledge of the characters and history,” he said. “So just having to draw characters I’d never heard of forced me to look at things form a new angle, look at the work of the creators that came up with them, and sometimes even at what the other guys were doing.”

Pérez agreed with that sentiment, saying, “It was always fun to see how each artist tackled the art challenge and what (we) as individuals could take from it, from an inspirational standpoint, to that of tools and effects utilized.” And that’s an important idea that several of the artists mentioned to me.

The friendly competition Comic Twart brought to these artists’ lives found each of them reflecting upon their varying approaches in different ways, with Shalvey saying it wasn’t in a “how can I do that?” way but a “why did I not even think of that?” one. It didn’t lead to each of them copying off each other. Instead, it drove them to work even harder to find their own voice and what they wanted to do with their work. As McDaid shared, “Submitting your work in that way, knowing that lots of people are going to look at it and leave feedback, and that you’re in a competition of sorts, is very good for artistic development, I think.

“It pushes you to do better, take risks.”

You can see the growth in the work these artists were putting out there, and it’s no surprise that several of its members went from relative unknowns to art giants. This was of course due to a mix of the creative push and the increased visibility Twart offered them, but look at Gerads as an example. He had drawn all of two comics by the time Twart launched, and now he’s an Eisner-winning, best-selling artist. As Fowler noted about Gerads and Shaner in specific, “I don’t want to say they wouldn’t be where they are without Twart, but I think it really helped them get to where they are.”

They weren’t alone. The Comic Twart experience helped each of them immensely in a variety of ways, as Fairbairn mentioned.

“It served the purpose of community, which you don’t get a lot when you spend your days alone in a room making comics. It served the purpose of networking. For those years there, I would seek out other Twartists at shows and just hang out with them,” he told me. “And the last one is that it was great at raising the profile of a lot of those guys. A lot of people discovered Samnee and Shaner and Gerads through this blog.”

“I very much believe a high tide raises all boats,” Fowler added. “If one of us was being successful then all of us were being successful. And it really helped put people in front of editors.”

“It was a weekly advertisement for who we are and what we could do.”

So, with all of that in mind, did this experience lead to work and other benefits for these artists’ careers? The answer is a resounding yes, even if not all of them gained work directly from the experience. For Shaner, who wasn’t well known when Twart launched, he found that the bigger names within the group – like Francavilla, Breitweiser, Fowler and Panosian – helped him gain a ton of visibility.

“My entire career came via the Internet and Twart had a lot to do with that,” Shaner said. “Being in that group, after a couple months it automatically bumped us all up a level, or at least that was my feeling. Plenty of (the other artists) likely would have been fine without it because they’re so talented, but for a guy like me who was still figuring out what the hell I was doing it had an enormous impact.”

Shalvey was working on a notable series already in BOOM!’s 28 Days Later book, and when he came over for his first conventions in the United States, he found that while people knew him for that work, “I could tell for the most part, from fans and editors, they knew me more from Comic Twart.”

“Some fans especially seemed really into the art blog and would support us all at shows,” Shalvey said. “It’s crazy how much attention and visibility (came) from something that was just meant to be a bit of fun with a silly name.”

Several of them picked up work directly from the Comic Twart experience, as Gerads lined up The Activity thanks to Twart and was actually hired for a coloring gig on BOOM!’s Starborn series from Stan Lee because of it, 8 Pérez did a cover for Archie Comics because of a “Rockwellian style” Archie piece he did, and Fairbairn was hired for a range of coloring jobs thanks to Twart, although that was mostly because it was his fellow Twartists doing the hiring. But my favorite hiring story came from Fowler.

“There was a writer who was putting out a novel and he was going to have Cliff Chiang draw the illustrations and cover for it. He sent Cliff a bunch of artwork to show, ‘This is kind of the tone we were going for.’” Fowler said. “This was when the New 52 happened, and all of a sudden no one had any time in their schedule anymore because DC decided to up the schedule on everyone by three months. So all of a sudden Cliff got very busy. So (Cliff) said, ‘You know, if you know what, why don’t you just hire the guy who did the art you sent me?’ The piece of art was my ‘Superman walks across America‘ piece.

“That writer was Tom King. And that book was Once Crowded Sky. 9 And Tom and I have been friends ever since.”

Fowler called Twart “a great portfolio builder,” and it helped every creator I spoke to and their careers, even if they were already gainfully employed at the time. 10 It had a trickle down effect, as sometimes it would lead to commissions and other times it would develop into comic work. Fittingly, though, the success of the blog led to its downfall, as McDaid told me.

“I think the blog’s eventual demise was partly due to this success,” he shared. “We all suddenly became far too busy to contribute to it anymore.”

It’s honestly hard to discern what the final theme was – it seemed that it could have been Top 10, Battlepug or maybe B.P.R.D. – but one way or another, Comic Twart largely ceased regular functions seven years ago tomorrow on July 10th, 2012. While the relentless Hawthorne has continued to catch up on themes he missed, 11 it’s largely derelict at this point, with Fairbairn paying for the hosting on the site to ensure it lives on.

“I wanted to make sure it was still up in some form just for posterity, I suppose,” he shared.

While it’s no longer active, it’s still a fairly frequently visited site – its site counter showed 1,722 visits in the past week, per my typing of this sentence – and one that has a legacy that looms large for the artists that participated in how Comic Twart helped them level up as artists, how it improved their visibility both in the short and long-term, and the relationships it fostered amongst them in the process.

Let’s be honest: if you’re an artist or a writer or whatever role you are and you find yourself inspired by Comic Twart to form a larger collective, that doesn’t mean your story will follow the same path as the one they did. Comic Twart is a moment in time that would be almost impossible to replicate, as all of the creators involved were on the verge of greatness, they just needed a little push to get there, perhaps.

But the fundamental idea behind this gone but not forgotten sketch blog is still a good one, and one that each of the people I talked to view as essential for creators and artists in particular. Finding a community of peers for yourself can be immensely beneficial to you creatively, professionally, and personally, and its value cannot be underrated.

“It is vital, I think, and it can be something that gets lost along the way when you’re racing to beat a deadline or refine your work,” McDaid said. “It won’t surprise you to hear that this is a very solitary job, and being alone for long periods of time is not all that conducive to good mental health…or even good art. Having other artists to compete with or share war stories with…it’s very cathartic.

“I would recommend seeking out a community to anyone. It’s a great way to grow as an artist and as a person.”

Pérez is someone who has belonged to many of these types of groups, as he’s been involved with webcomics collectives like DayFree Press and TX Comics, art squads like HIVE and Comic Twart, studios like RAID, and even more casual ideas like Superman Club, a lunch group started by the late, great Darwyn Cooke. He keeps finding himself in these groups because he recognizes the value they have.

“I think it’s very important for artists to be part of a community. After I left college it was the one thing I truly missed – being surrounded by peers, learning from them, and being inspired by them, and not to mention the camaraderie,” Pérez shared. “With all of these I experience not only a growth career wise, but also with my skill sets as an artist as well as a business man.”

Even though my interview with him was over email, I could feel how much the Comic Twart experience meant to Shaner, who described it as “massively important” to him. At the time, he was the youngest one in the group, barely a year out of college and someone with few credits on his resume. He calls himself “very fortunate” that he was included in the group and “given a chance to grow as an artist.” Because of that, he’s a big believer in the value of community for artists.

“Even if there isn’t a regular drawing component like we had, having a community like that to call on is vital for somebody figuring things out on their own,” Shaner said. “It helped me feel like I was going to make the comics thing work and that at the very least I’d made some friends in the industry.

“So many of us spend so much time alone that being able to go back and forth with peers is huge, and that went double for me at the time because I’d gone from college where I was constantly surrounded by friends and people my age to spending the majority of my day by myself.”

Samnee called finding a group “incredibly important,” and something that was worthwhile for him if only because of how it drove him to up his game and helped him find good friends that gave each other “support and encouragement” as they all advanced in their careers.

While Shalvey is a bit dubious of the potential for something like this in the social media era, as everything is so public, he still believes it’s “imperative that artists find a community.”

“One needs a surface to bounce ideas off of to see if they work, or don’t work,” he said.

That’s a sentiment that Fairbairn echoed, as he believes you can’t “make art in a vacuum.”

“I think you need to have peers and readers and as much input as you can,” Fairbairn told me. “At least from a career perspective, I think it’s really invaluable that I made the connections that I have through online communities like Gutter Zombie.” 12

For Fowler, the opportunity Comic Twart provided him gave him a chance to pay something forward that he was given when he first started. When he was getting into comics, he met Steve Lieber – whom he refers to as “my rabbi” – and Jeff Parker, and throughout his whole career, they’ve basically been his “big brothers,” guiding him or checking him whenever he needed it. They’re relationships he dearly values, and Twart allowed him to do that for the generation that followed him.

“The last generation helps the next generation because nothing is achieved by getting in somebody’s way. It doesn’t help their career and it just means there are less voices to be heard,” he said, before adding about the Twart experience, “It helped me feel really positive just about making art. It’s something no one really tells anyone when they’re getting in. Depression and imposter syndrome, they’re very real parts of life as a cartoonist.

“I’ve gone through really low patches. If I’m honest, I was probably going through a low patch when we started Twart. And it helped me get out of it because I was having fun drawing.”

These relationships you forge and foster as a creative can mean everything to you, your work or your career, even if eventually you and your peers have to move on like the Comic Twart squad did. The history of comics is dotted with these kinds of groups that came together for a time but eventually had to separate, even if they still felt a kinship with one another going forward. And it’s not always a sketch collective. Sometimes it could be a message board like the Warren Ellis Forums or Gutter Zombie or even something as simple as a local drink and draw group. These communities can change everything for creators, even if it may not seem like that at time. That’s why they’re so important, as Hawthorne told me.

“If you can find a crew of people that are talented, keep you honest, keep you moving forward…that right there is magic,” Hawthorne said.

“Find that at all costs.”

Big thanks to Fairbairn, Fowler, Hawthorne, McDaid, Pérez, Samnee, Shalvey and Shaner for talking with me for this piece.

It was even then, but it’s possible we didn’t recognize it at the time.↩

Remember, this was before the “Like” button on Twitter was the “Like.” It was originally the “Favorite” button.↩

This was also back when Twitter counted user names as characters, so as Fowler shared, the conversation quickly became untenable on the platform because they only had enough room to tweet things like “YEAH!” and “WOOO!” at each other because of how many people were involved.↩

Twitter was also purely timeline driven at the time, so if you missed a tweet, you basically never saw it again unless you already knew it existed.↩

Dan McDaid was the other one, as he’s from Scotland.↩

A free month subscription to SKTCHD to whoever finds it!↩

And they did add a lot to the pieces he colored!↩

One of my favorite anecdotes from my interviews was from Fairbairn, who said he used to bust Gerads’ chops for his colors on Starborn, leading to Fairbairn offering him technical tips. “It’s just funny to me that there was a point where I was giving Mitch Gerads tips about color. (laughs) It’s a conversation that would go the other way these days.”↩

This was King’s novel that preceded him becoming a household name in comics.↩

For example, Samnee was in the midst of his renowned run on Thor: The Mighty Avenger at that point.↩

His last piece was on August 11th, 2016.↩

This was a forum for colorists that was run by Dave McCaig. Like Twart, it’s now defunct.↩