Variant Covers and the Infinite Game

Let’s take another look at the proliferation of variants, and the complex nature of their existence.

It probably wouldn’t surprise you to learn that my inbox is often filled with messages from people within comics. That comes with the territory of running a comic site and podcast. Most are focused on promoting something or responding to my initial email, but occasionally, someone reaches out in hopes of getting me to investigate a topic. Maybe it’s a frustrating trend, a new and exciting arrival, or simply something they’re intrigued by. Whatever it is, these draw my attention, as it’s always interesting to see what people in comics are curious about themselves.

While these emails are unusual, there is a topic that’s routinely at the top of the list when they do hit: variant covers. 1 The questions vary, ranging from “What’s the deal with them?” or “Why are there so many?” to “Do people actually like them?” or “Are they really selling?” Whatever the query is, the subject remains the same, and it always feels rooted in a place of uncertainty, as if there’s a pervasive sense of foreboding surrounding this house of cards the direct market 2 has built for itself.

That’s part of the reason this topic has been the subject of multiple features on the site already. There’s genuine curiosity about variants — both from myself and others — and a level of interest that requires something beyond a surface level look. But something else has ensured this would be a recurring feature on the site. That’s just how common they’ve become. Once they were a regular part of the single issue mix, but now? They’re overwhelming, a dominant ingredient in the alchemy of the direct market.

Just how significant have variants become? Consider this. The era most frequently compared to today’s variant-rich slate is the 1990s, a stretch that’s perceived as the other high time for these covers. But the average month of releases from comic shops this year has had considerably more variants published than the most significant year from that decade. We’re in uncharted territory now, with the usage of these covers continuing to expand into shocking, previously unimaginable levels.

Maybe that’s why my conversations about variants have increased. It’s difficult to not feel that these covers aren’t just a part of comics these days, but a requirement for success within the direct market. They’re the price of doing business, with the right cover artist being as essential to your project popping as the people working on the comic itself. That can be exciting. It can also feel onerous, a compulsive necessity out of fear of failure. And it only continues to accelerate.

That’s why it’s the right time to revisit this subject, and to get a feel for just how robust the variant game has gotten, how those inside the industry view these covers, and what that might mean for the direct market going forward.

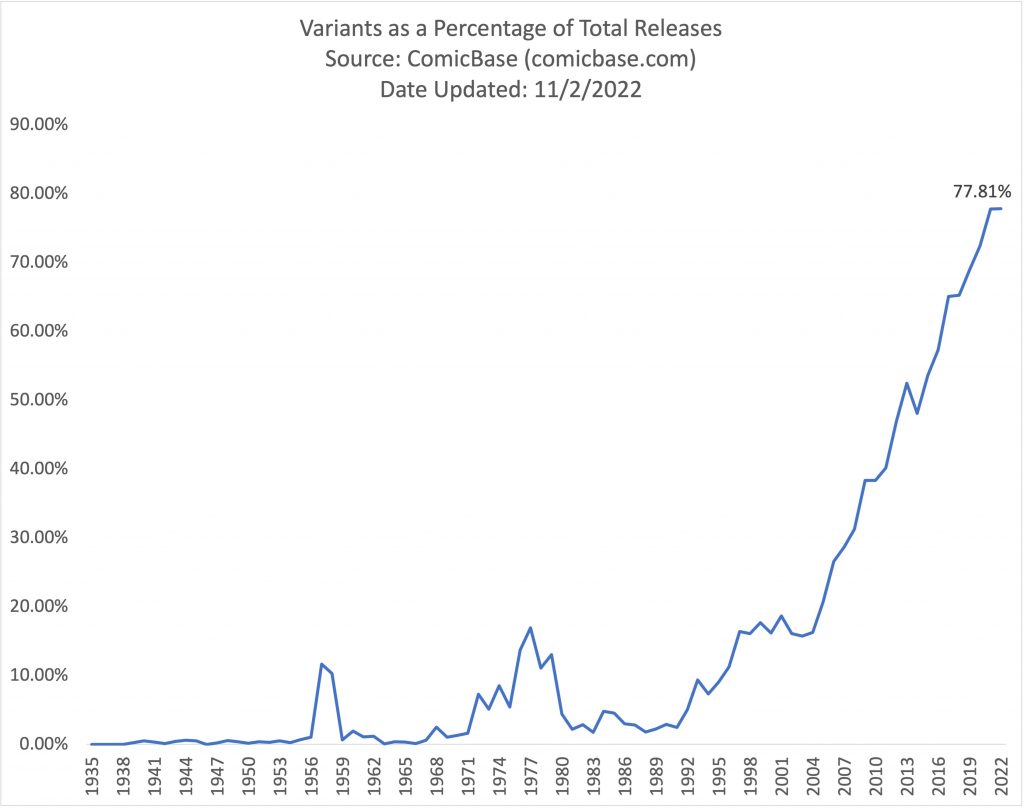

You probably don’t need to be told that variants are rather abundant these days. All you need to see that is a tour of your local comic book shop on a Wednesday or to a cursory browse through the week’s releases. Just because you understand that, though, doesn’t mean we’re not better off establishing what this really looks like. Let’s expand beyond the anecdotal and dig into just how pervasive variants really are by looking at some charts, starting with one that showcases variants as a percentage of yearly comic releases in the U.S. market going back to 1935. 3

This chart expresses the percentage of all comics that are a variant, meaning non-main, or A, covers. As previously noted, this trend has had a slightly upwards trajectory of late. You can certainly see that here. The two biggest periods of growth for variants were 1991 to 2003 and 2004 to now, with the former being dwarfed by the rapid climb of the latter. We’ve reached a point today where more than three quarters of all single-issue product available for order by comic shops is a variant. That’s a staggering number.

That said, this chart never feels like an adequate way of conveying just how absurd the numbers really are. Let’s look at another that’s a different spin on the same data.

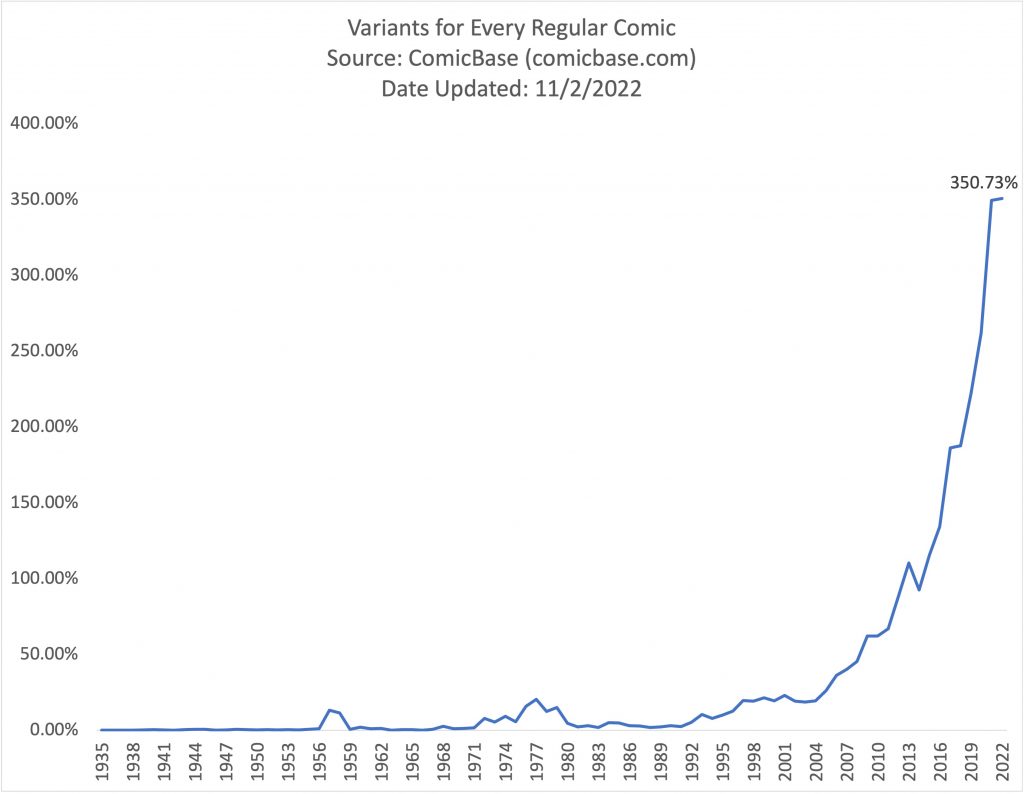

This chart depicts variants relative to individual comic releases. The easiest way to think of it is like this: for every 100%, there’s one variant for every comic book release. That means in 2022, there have been an average of slightly more than 3.5 covers for every single comic in the market. 4 Sometimes there’s more, like with a #1 or anniversary issue. Sometimes there’s less. But it averages out to well over three covers per release, a number that’s insane on its own.

Contextualizing it doesn’t help matters. I previously mentioned that there are more variants in an average month from 2022 than in the biggest year in the 1990s. That year was 1997. When you match 2021 — the most recent full year, albeit a pandemic-influenced one — up against that year, you find that while it had just over 72% as many total comic releases as 1997, it had over 1291% of the number of variants. 1291%! Put simply, there were nearly thirteen times as many variants in 2021 than in 1997.

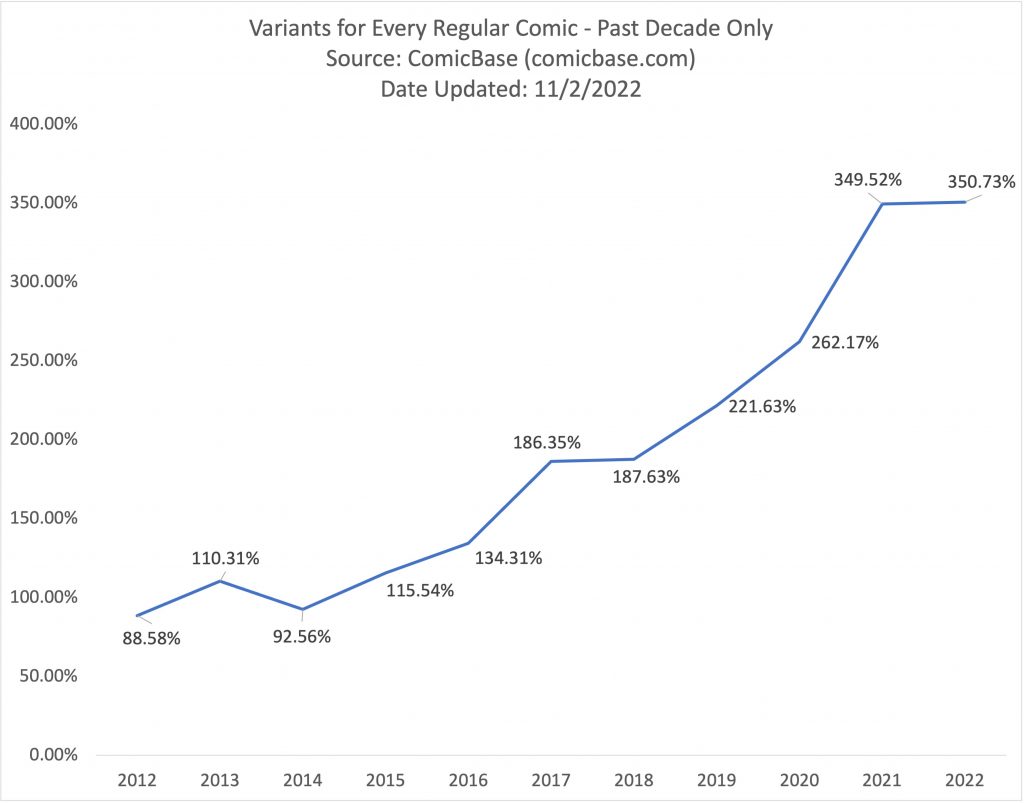

Those are massively different eras, of course. Apples to oranges, one might say. But limiting the timeframe barely helps. Here’s a closer look at the last chart, with this one only exploring 2012 to 2022.

The last year that averaged fewer than one variant per release was 2014. 5 Since then, that ratio has nearly quadrupled. Save for the relatively flat growth from 2021 to 2022, it’s been an Everest-like ascent since 2014, with upcoming release lists giving little indication that this trend might head in the other direction.

Now, it’s worth noting that per Comichron and ICv2’s most recent analysis of yearly sales data, 2021 was a banner year for both single issues and comic shops. Variants exploded to dizzying levels just in time to see the greatest revenue numbers in the history of that duo’s reports. That almost certainly played a part in those gains, with the wide selection of covers bolstering direct market performance in a real way. It’s clear there’s value there.

But for those in the industry, do they feel like a necessity to succeed? That’s the real question.

Naturally, the role of the person you talk to will go a long way to determining their position on variants. Amongst the creators I talked to, for example, the perception is that variants are effectively a requirement to achieving success with your work. 6 How that manifests itself varies dramatically on an individual basis, of course.

Writer/artist Chip Zdarsky exists at one pole. Zdarsky readily admits that variants are “a necessity across the board,” both for creators and publishers but also comic shops. It’s his belief that without them, many comic shops would fail. But that doesn’t mean he’s a fan, with his success allowing him some relief from the form.

“I’m at a stage in my career where I won’t do variants,” Zdarsky said. “I won’t draw them for other companies. The one I did for my first issue of Batman was my last one. I’m not saying never, but at this stage, the way I’m feeling about the industry, the environment, the world, I just don’t want to contribute to it.”

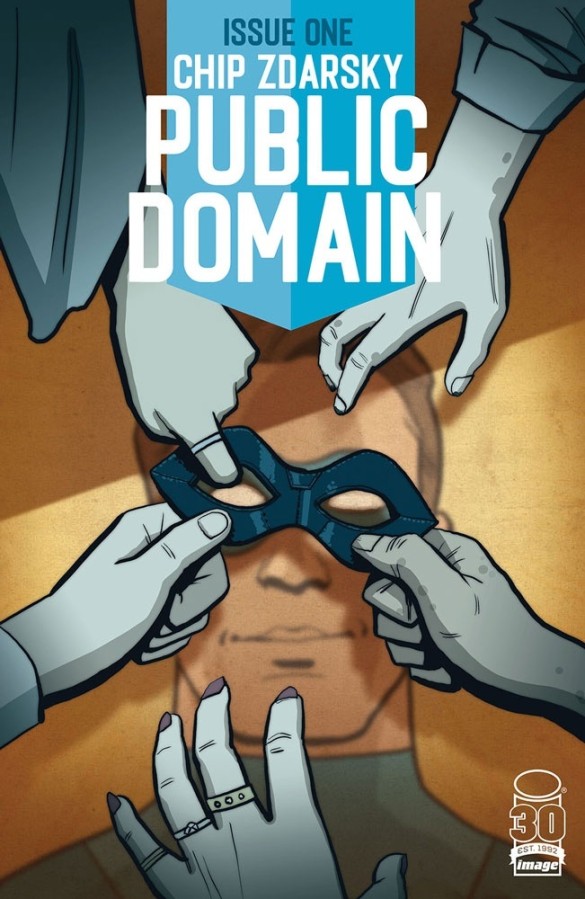

Variants are even largely absent from his Image series Public Domain, with the sole exception being one he promised as part of his rewards for Substack subscribers. Zdarsky knows his ability to avoid them is a product of his own success, to some degree. He recognizes that other Image titles need those variant sales, as they can help “fund your entire first arc, if not the first 15 issues of your book if you’re smart about it.” But he prefers to avoid the collecting and speculation game as much as possible, a choice others might make if afforded the opportunity. 7

On the other end of the spectrum is writer James Tynion IV. There are few who play the collector game better than Tynion, and it’s something he continuously experiments with from project to project. As he shared with me, “selling a comic book is about activating my different fanbases, and what the last few years has taught me is that I have a very strong following in the collector community.” It behooves him to give these fans what they want.

“Releasing a book with only a single cover, where there isn’t the kind of joy of the hunt that exists for that community, might not get that community to show up in large numbers,” Tynion added. “If I want to activate everybody who has supported my titles in the recent past, I need to lean into the variant market.”

Tynion’s realistic about it, though. He tries “to do this in a measured way.” While he describes a title like Something is Killing the Children — something that is to some degree out of his control — as “its own beast,” he makes carefully considered variant decisions on his own projects. For Tynion, it’s about achieving a delicate balance, one of serving his market without burning it out. But variants are a crucial part of his formula.

It helps that Tynion enjoys them. In fact, most creators I talked to like them, at least conceptually. And I’m not just talking about the financial benefits. Writer/artist Declan Shalvey emphasized how variants give him the chance to see what legends like John Paul Leon and Marcos Martin and up-and-comers like Justin Mason and Gavin Fullerton would do with the characters and worlds he created, something he described as “just cool.” Bringing in your own favorite comic artists, or even talents outside the medium, to provide a singular piece of art for your project is hugely appealing to those I talked to.

For artists, variants can even offer a fun, high-paying project that’s a bit more creatively free than main cover gigs, which typically must connect to the plot of the comic. When someone uses that freedom to consistently deliver standout pieces, they can even build a career around the form thanks to the number of jobs that have opened in this variant-rich period we’re in. 8 People like Artgerm, Jenny Frison, Peach Momoko, and others have become so consistent at delivering effective pieces — and drawing collectors along with them — that they don’t even need interiors to succeed in comics. That used to be rare. Now, it’s a growing segment of the medium.

One side that’s a drag, though, is when variants are so ubiquitous they’re effectively meaningless — or even result in unattractive, unappealing work. Zdarsky noted that the comps 9 he receives from the Big Two are often filled with endless retailer variants that “are just ugly or only slight variations” of one another. It can be difficult to see the value when little about the work stands out, with each existing as just more grist for the mill.

Overall, though, the creators I talked to — both on the record and off — were generally positive about variants. This isn’t too surprising, really. They are fruitful financially, allow you to work with more artists you love, and can provide artists an opportunity to supplement their income. There’s not a lot of downsides there, outside of the ones Zdarsky laid out. 10

There are even fewer from a publisher perspective, which should be even less of a surprise. For publishers, variants are almost entirely additive. The only additional costs are whatever it takes to commission a cover from someone and print them. There’s a reason the usage of variants is through the roof: they make publishers money at little cost.

I reached out to varying houses for this piece, and somewhat predictably, not many responded. In fact, there were only three. 11 Of those three, two agreed to participate. Just one actually answered my questions.

It was Vault Comics’ CEO and Publisher Damian Wassel, someone who is as open and honest as anyone in comics. Per Wassel, Vault has “a standardized approach for retailer incentive variants, and a bespoke approach for other special variants for each title.” They know what they’re going for. Sometimes that manifests itself in an assortment of variants for a title somewhat deep into its run, like the quartet for last week’s West of Sundown #6. Other times it’s as few as just one, like with this week’s Mindset #5. It’s about finding the right answer for each title.

Wassel’s view of variants is that there is some level of necessity to deploying them for new launches and the issues that follow beyond that, if only because they can “catch additional readers.” Perhaps a customer loves an artist who worked on one, or maybe the piece depicted a scene or character in an appealing way. Whatever the reason, Wassel believes variants can create new readers for a title. They “also appeal to collectors,” which is an important part of this story.

Let’s talk about collectors for a second. Variants are often considered the domain of collectors and speculators rather than readers. The belief amongst some is that if you’re intentionally buying a variant, you’re either someone who buys specific or multiple covers, or you’re trying to profit off reselling the release. This is not always true. 12 But variants are believed by some to be inseparable from those types of comic buyers, with how you feel about the former dictating your thoughts about those customers. That said, Wassel told me “It’s really hard for me to see (appealing to collectors) as a bad thing.”

“Collectors get a lot of grief in conversations about comics sales, but most of the collectors I know who are out there buying indie books are also serious readers, lovers, and evangelists of the medium and the books they support,” Wassel said. “Obviously, we all want to bring new readers to comics, and I think collectors help with that far more than they are given credit for.”

Wassel’s not the only publisher who has mentioned that to me. It’s been suggested that the collector conversation, and variants along with it, can act as a focusing tool for customers. Attention from collectors can draw interest from other customers, while a significant presence on the shelf can catch their eye. You might not buy it, but it’s one I’ve heard enough to believe it, to some degree.

Despite their belief in the benefits of variants, Vault’s still conscientious of the potential downsides. As Wassel told me, they are “keenly aware of what happened in the 1990s with the speculator boom, and we make sure Vault does not contribute to a similar situation happening again.” To prevent that, Vault offers retailers returnability on first issues, “even when those issues have a robust incentive variant program.” That approach ensures that risk is shared, and that shops can order with faith that they won’t get stuck with boatloads of unused inventory.

This is not how all publishers operate. But it is welcome.

While creators and publishers have every reason to endorse variants, retailers can be understandably trepidatious of them. Sure, variants can benefit shops. But they can also be costly in more ways than one. If anyone would be sensitive to this growth trend, it would be them. That’s why I asked them directly: Are there too many variants right now?

“There are way too many variant covers today,” Patrick Brower of Chicago’s Challengers Comics + Conversation said.

“These days, the numbers are ridiculous,” Bruno Batista of Dublin’s Big Bang Comics added.

The perception seems to be that publishers are deploying far too many variants for comics that have little reason to have them. Variants used to mostly belong to notable issues, but now, any release could come with a veritable alphabet of covers. Brower cited how recent non-milestone issues of Batman and Mighty Morphin Power Rangers had seven and nine covers respectively, numbers that bolster the bottom line of publishers but rarely match in-store demand. In fact, they can even confuse customers instead of energizing them.

That manifests itself when someone at Challengers looks for a previous issue in a specific title’s stack, 13 and then shows up to the register with multiple covers of the same issue because they have no idea what they’re buying. As Brower said, “Almost every time (the customer) didn’t realize it was the same book,” which causes frustration rather than excitement. That’s a problem.

In the eyes of Travis Pratt, the owner of California’s Current Comics, sales mostly only warrant one or two variants per release outside of milestone issues for Big Two releases. When there’s more, it can result in a level of ubiquity that makes them harder to sell instead of enhancing them. If everything is special, nothing is special. Maybe that’s why Challengers has to sell some 1:25 incentive variants 14 at cover price. Even hot ticket items aren’t that hot anymore.

The only shop that didn’t end up on the “too many variants” side was Third Eye Comics’ Steve Anderson. Third Eye does well with variants, and while Anderson has always heard that there are too many from his peers, he’s also heard there aren’t enough. That’s why he believes the answer to that question is a little more complex than any simple binary. 15

“I think the answer to your question is this: is the book a book that you can sell variants on? If yes, then there’s never too many variants,” Anderson said. “Is the book a book that you can’t sell variants on? The answer is there’s always too many.”

Maybe he’s on to something there. Most said that variants can still have a significant impact on sales. The problem is it can be difficult to determine which will hit, at least outside of the surest selling artists and titles. It can cost shops sales when they guess wrong, as Brower said.

“I know we don’t have to order every cover, but we risk disappointing someone when they want a specific cover,” Brower told me. “For something as simple as Buffy, we usually just get the ‘A’ cover, but we have a dedicated non-subscriber who buys one copy only per issue and wants a specific cover each time, and it varies.

“If we don’t have the ‘B’ cover and that’s the one he wants, he just doesn’t buy Buffy from us that month.”

Variants make the ordering process incredibly difficult, between the mathematical gyrations of gated variants and having to choose from a variety of options. As Batista told me, “You can’t order a significant number of each ‘just in case.’” The only way you can truly know someone wants one is if they specifically request a cover. But with publishers often revealing variants right before final order cutoff, 16 many customers never even get the chance to do that. It turns the whole endeavor into a guessing game, creating a situation where it’s “simply not feasible” for shops like Big Bang to order everything. That’s a tough spot to be in.

The bind this puts shops in affects everyone, even those at the top. Pratt admitted he only orders variants for the shelf for about a third of Marvel’s releases. And that’s Marvel. Getting buy-in on Cover D is even more difficult when you’re a smaller publisher.

That ties into a crucial note several shops mentioned to me. With the number of variants out there, you must be smart about how you order. You can’t order beyond demand or your means. That’s why Anderson described variants as “a bonus” and “never a reason to stretch” your orders. They’re “a little something extra to help a shop maximize profit potential and minimize risk.” While “building your business around variants is not sustainable,” the veteran retailer told me “There’s no reason to not market and sell them to customers who love them.”

“Everyone finds joy in some aspect of collecting, and every part of our market is important and valuable,” Anderson added.

Not every shop is like Third Eye, though. While most agree that there are too many variants, publishers “wouldn’t keep making so many if stores didn’t keep ordering them,” as Pratt told me. Whether shops do so in a way that benefits themselves and their customers is uncertain, though. That’s where the cost lies.

This subject would be a lot easier if there was a simple answer to how worthwhile they are, like “variants are bad because…” or “they are good because (insert reason here).” Variants remain a far more complicated topic than anyone prefers, with the value truly being in the eye of the beholder. While there’s no easy answer, I’d argue that there is one absolute truth amongst all the feedback I received, and it’s something Anderson said.

“I’ll take there being too many variants with the option for me to skip if I desire then the alternative of the publishers discontinuing variants and completely removing my choice to purchase,” Anderson told me.

Some might believe that variants should go away. I’m not sure it’s as simple as that. Erasing them altogether would likely be as harmful a direction as the one we’re currently headed in. As Anderson noted, at least retailers and customers can choose whether they want to opt-in. Even Brower, someone who is no fan of variants, admits that “there are a significant number of comic collectors that love variant covers and I need to acknowledge that in ordering.” There’s value there.

But it’s hard to look at the rapid ascent of variants and not feel as if it’s gone a bit too far. We might be seeing some sort of correction already, with 2022 plateauing to some degree after 2021. It’s just difficult to not see three and a half variants per comic release as anything but the very premise gone awry. They’re meant to be special. When they’re this common, they just aren’t anymore. It doesn’t even seem to be about servicing market demands at this point. Instead, it feels like some publishers are admitting that they have no idea how to sell comics without a deluge of variants.

This all reminds me of an article I read recently in The Atlantic, in which Derek Thompson wrote about Moneyball 17 and how that has infected our broader culture — with an immense cost coming along with. In it, Thompson cited a theory by James P. Carse about how there are two types of games in life, infinite and finite. The premise is that finite games are designed to have defined winners and losers in the near-term, while an infinite game “is played to keep playing; the goal is to maximize winning across all participants,” as Thompson put it. In short, the former focuses on the competitive and short-term, while the latter is collaborative and meant to keep the larger idea of something going in the long-term.

As I read this article, I couldn’t help but think about comics, and the place the direct market finds itself in today. It can feel as if every decision within it is made in service of the finite game, as many endeavor to find short-term wins above all else. Variants are the perfect example of this. They often — not always, but often — are built on selling more copies of a comic to the same people already buying it. It’s about squeezing every drop out of a single comic and single customer, maximizing profits for the publisher releasing it with little thought at times outside of your immediate area.

That’s not to say everyone does that. Vault has a balanced approach, with that offer of returnability even on debuts loaded with variants being a nice trade-off of risk. Wassel’s point about the potential impact of collectors and how that can lead to gains in the short to medium term feels right. But as he noted, “Who the heck knows what the long term holds?”

That’s especially the case in a market that finds comics well into their run coming with 16 covers, like Dynamite is doing this week with Vampirella Strikes Vol. 2 #7. There’s no reason for that beyond lusting after sales. Dynamite isn’t alone in that regard, either. And when variant programs are sometimes seemingly designed around flooding the market with little consideration of your partners, that’s a risky proposition in the long-term. As Zdarsky put it, “the fact that we’ve come to rely on variants so much is a little dangerous.”

That’s because the direct market is an infinite game, at least in theory. The best version of it would find all involved – publishers, creators, retailers, etc. – working collaboratively to maximize the longevity and success of the industry and medium. Variants are a valid addition to the mix, a useful tool when supplied to service demand. But when this onslaught is the norm, it’s clear that some are no longer invested in that collaboration.

Everyone understands the game and how it’s played. There’s a balance that can be found, one that builds for the present and future. The problem is, if we want it to keep it going, something will have to give. To get there, a little more thought might need to be put into the infinite game of comics, which isn’t always the easiest thing for this industry to do, as one retailer noted.

“Everyone is going through tough times, and that includes the publishers,” Batista said. “I 100% understand that they are trying to maximize their profits, but more covers aren’t a long-term answer.

“But then again, it’s not like the comics industry is known for thinking towards the future, is it?”

I’m not going to in-depth about what these are, because this topic has been addressed here many times before, most deliberately in this piece. But the short version is, variants are effectively any cover that isn’t the main cover to a comic book.↩

Or the comic shop side of the comic industry.↩

With all data provided by Peter Bickford of Comicbase.↩

Or, expressed in total, there have been 11,490 variants released in the U.S. market as of November 2nd, with those belonging to just 3,276 comics.↩

Which was the second most significant number in the history of comics up until that point.↩

With Saga cited several times as the lone variant-less title that is currently thriving.↩

As one creator put it to me, “If I were launching a creator owned book, I think I’d have a really hard time with it.”↩

Having 12,000+ variants means you need to find artists to draw all those.↩

Or the free copies a creator receives for working on something.↩

Shouts to Chip for touting the environmental impact, though. I’ve long felt uneasy about how many trees it takes to get to the numbers necessary for high order gate variants, which is especially tragic considering a lot of those comics that are ordered to get that variant never sell.↩

Which is far fewer than any other time I’ve written a variant piece in the past.↩

There are many reasons you could buy a variant. Take me as an example. I sometimes buy them by accident or because there is no other option!↩

Challengers puts back issues underneath the current issue, which is a fairly common move.↩

Meaning you have to order 25 copies of something to order one of this variant.↩

To add to that complexity, one retailer told me that the problem isn’t the number of variants today. It’s that there are too many comics that are simply not sellable, so naturally, the variants won’t move either.↩

Or FOC, the final day shops can change their orders.↩

A trend in baseball built on optimizing the game around the mathematically correct choices for each facet of the game.↩