“The World’s Greatest Heroes! The World’s Greatest Comics!”: How Wednesday Comics Went from a Wild Idea to an All-Time Great

When you look back through comic book history, the most iconic works often have one key characteristic in common, and that’s that they strived to do something different. Whether you’re talking The Dark Knight Returns and its out-of-continuity yet quintessential take on Batman or something like Maus and its fierce confrontation of an atypical subject matter for the medium, comics are often more interesting when they zig while everyone else zags.

That’s not to say there isn’t huge downside to that approach – please see Marvel’s Trouble and the failings that come with exploring the sexy early years of Aunt May and Peter Parker’s parents – but at the very least, it’s a path to being memorable, even if it’s more “infamous” than famous. And the upside is worth all of those notable misses. With greater risks come greater rewards, and the history of the comic book medium is littered with proof of that idea. 1

A perfect example of this turned ten years old this year. Like other luminaries, it was a bold, abnormal premise for the often risk-averse comics industry. It was a throwback to yesteryear that married some of the greatest creators in the history of the medium with exciting newcomers in a format that was decidedly antiquated, yet charmingly so. It was the definition of a passion project by one of the most impressive and underrated comic book minds of the past 30 years, and it was all the better for it.

It was Wednesday Comics, a 2009 anthology title at DC Comics. Published in broadsheet, newspaper format to simulate the experience of reading the Sunday funnies of the past, it was a risky move, and one that never became a giant hit or even an awards season giant. But those that did read it recognize it for what it is: one of the most interesting and iconic works of this century, and one that stands tall amongst the legendary efforts its brilliant ringleader edited. This is the story of how a mad idea became something real and magnificent, thanks to the efforts of a particularly driven man and the exceptional creators he recruited.

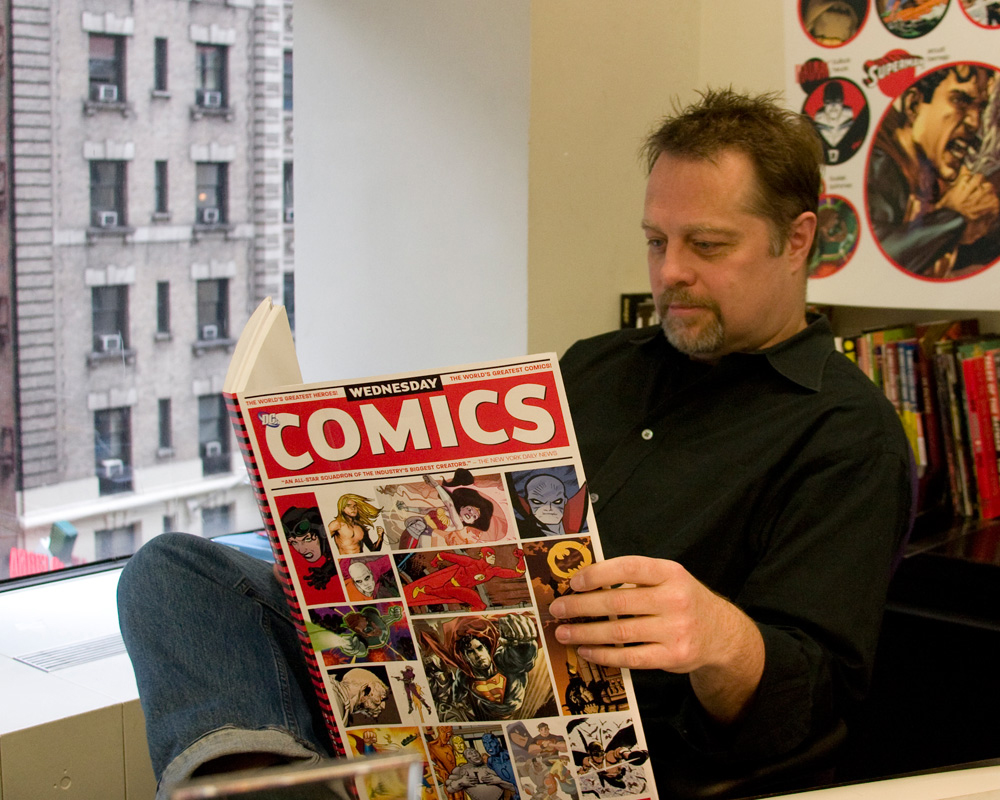

At the time Wednesday Comics arrived in comic shops, Mark Chiarello was the Art Director at DC Comics, a title with deep significance and a rather broad slate of duties. This role was “ever evolving,” according to Chiarello, as he “consulted on every piece of artwork that came through DC” during his time there, including covers, periodicals, advertisements, convention graphics, book designs, online graphics, posters and more. Beyond that, he took on special projects, which is what he might be most well-known for.

“Once in a while, if I had a free moment, the bosses would let me come up with a project and edit it, like Batman: Black and White, Solo, (DC: The) New Frontier, Poster Portfolio, and Wednesday Comics,” Chiarello told me, as he listed off what might as well have been a shortlist of the most interesting DC titles of the past two decades. With a track record loaded with award-winning titles that attracted the best and the brightest of the comic industry, you’d think that would have meant he’d have carte blanche to bring these to life. That was…not entirely the case.

“There was never a lot of freedom really,” Chiarello said. “I usually would have to go up to Paul Levitz’s office and plead and beg to do one of my ideas. The answer was usually ‘no,’ but I realized that if I kept going back up there and being a pest, Paul would say ‘yes’ just to shut me up.”

Chiarello was pals with comics legend Alex Toth, and their discussions about the brilliance of comic strips from the 1930s, 40s and 50s was a moment of inspiration for the art director. While Chiarello was too young to have read those strips as they were released – most notably adventure stories like Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates or Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant – his chats with Toth inspired him to look back upon what he missed, and from that, the kernel of an idea was born.

“At some point, I started collecting those old strips, and one of the aspects of them that knocked me out was the sheer size of the artwork printed on those enormous pages,” Chiarello shared. “I thought, ‘let’s do that with the roster of DC characters, like Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman.’”

And that’s exactly what he set out to do, as his vision was producing not just a comic book with those kinds of strips, but a title printed like a newspaper with a collection of one-page strips which eventually formed a full story when the entirety was published. These strips needed to be iconic, unique takes on DC’s characters, and he envisioned them as a mix of angles from a variety of creators covering a diverse set of tones. Green Lantern artist Joe Quinones described it as a “spotlight” on the creative teams who worked on it, showcasing what each was capable of, with the hope being that for readers, “the tactile experience of opening up a piece of newsprint” led to a visceral experience you couldn’t find anywhere else.

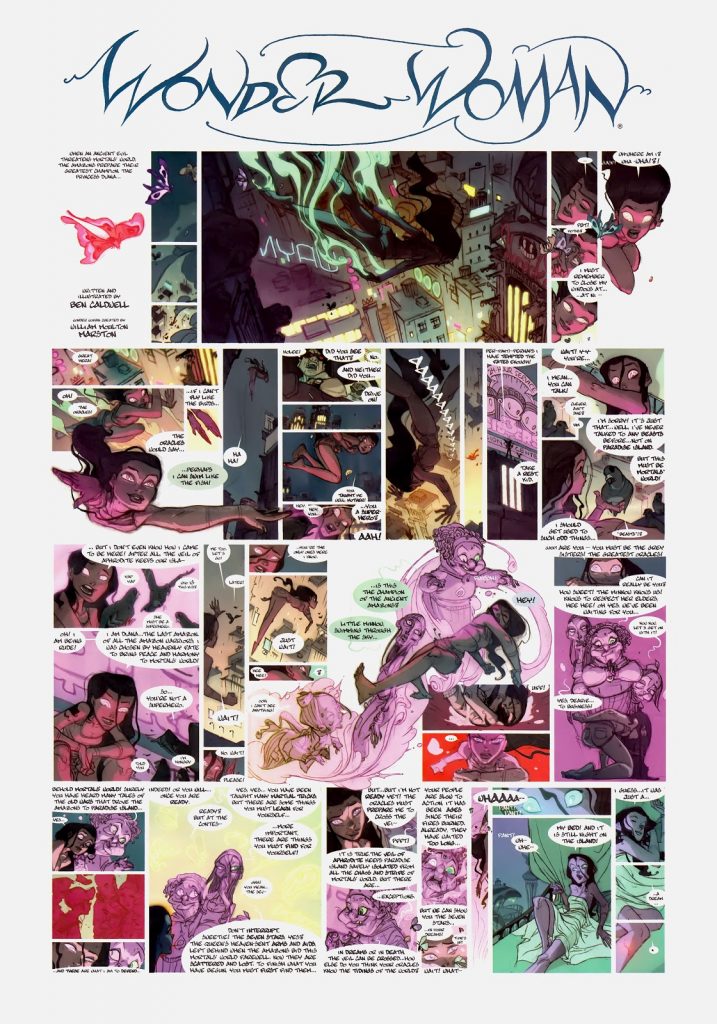

It was a good idea, and a fun one at that. Unfortunately, even good ideas take time. But eventually, Chiarello got his way. Once Levitz was sufficiently convinced and greenlit Wednesday Comics – a process Wonder Woman cartoonist Ben Caldwell suggested took over three years, from what he understood – it was time to start recruiting.

For that, Chiarello “simply made a wish list of the talent” he wanted to work with and got to calling. He “didn’t want to confine it to the already established big shots in the business, but also wanted to invite some newer, up-and-coming artists and writers as well.” To recruit the list he was going for, you need to either have some serious chutzpah or you need to be rather well-respected. The good news for Chiarallo is he wasn’t lacking in either regard.

“To be honest, if Mark Chiarello calls you and asks you to be part of one of his personal projects, you do not turn him down,” Supergirl writer Jimmy Palmiotti told me. “If he asked me to write a character I hated, I would have done it for him. He was the top gun as far as editors and creators went and his call had to be answered.”

In fact, the only creator who received an invite but didn’t sign up was Steve Rude, “who initially accepted but then had to bow out,” per Chiarello. Schedules didn’t line up for the Nexus co-creator. But for everyone else, it was an easy decision.

Amongst the newer set of creators, there were some interesting stories of how they came on. Caldwell – whose comics experience was rather limited at that time – had an advocate in Chiarello. The veteran DC man saw something in the artist’s work and was looking to find the right gig for him. According to Caldwell, they happened to meet either the day before or day of Wednesday Comics approval, and when Chiarello pitched him, he couldn’t resist.

“It sounded way outside of my pay grade, but I was all for that.”

The Flash artist Karl Kerschl had worked with the Scarlet Speedster before, so when Chiarello reached out with an offer to revisit the character, it was an easy call. As he said, he “would never say no to Mark Chiarello for anything.” Where it became interesting, though, was how his collaborator came onboard. At the time of the offer, there was another writer potentially set to tackle this with Kerschl, but that fell through. When that happened, Kerschl said, “Look, can I just do it myself? I’d like to bring my friend Brenden on because we’ve been working together on stuff for years.”

That was Brenden Fletcher, his Isola co-creator. At that point, Fletcher had given up on comics and was working at a newspaper, so when he was given the chance, he couldn’t say no.

“I mean for me this was just taking some time after my day job and messing around with my buddy and talking about the stuff we talked about anyways,” Fletcher said. “It was a no brainer for me.”

Quinones came onboard thanks to two fateful meetings. One was when he was living in Maine on the grounds of a camp 2 – well before this project came to be – when, bizarrely, Chiarello visited the camp to see how it’d suit his kids. The two met during his visit, the former shows the latter his art, and yada yada yada, a while later Quinones gets his first work at DC Comics on Teen Titans Go at least in part because of that coincidental meeting.

Then, when he was trying to escape the confines of the young readers line, Quinones visited Chiarello at his DC office and happened to spy the plans for what would become Wednesday Comics. The artist locked that idea away in his brain, and when Quinones met writer Kurt Busiek at a con the next month, he pitched Busiek on maybe working together on that. A few months later they were on their way.

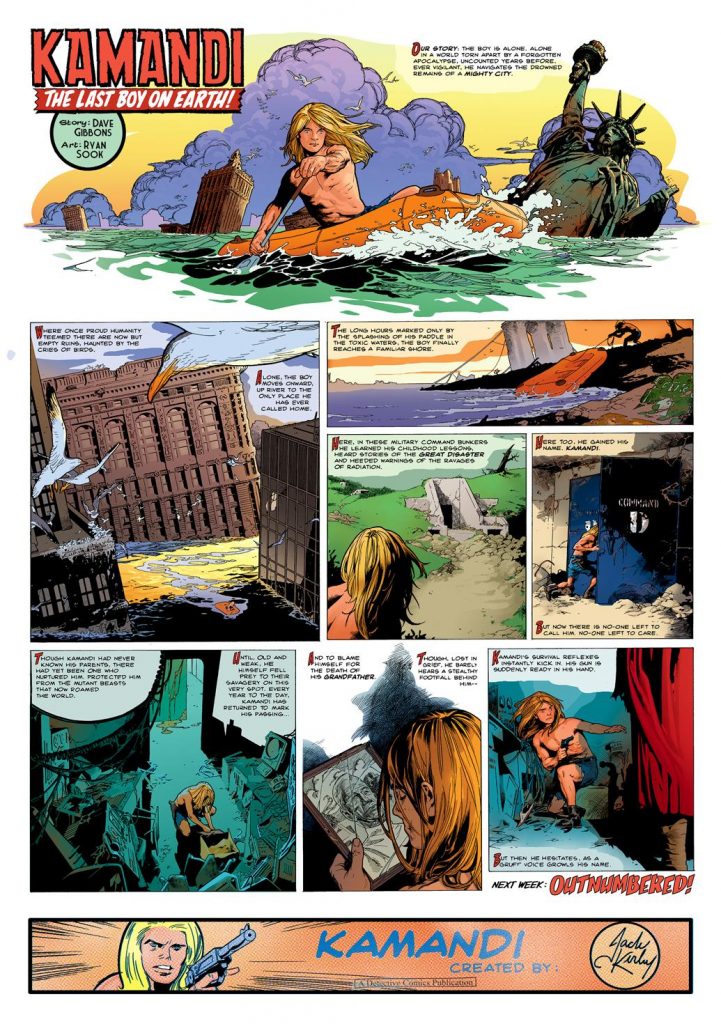

When it was all said and done, Chiarello assembled an unbeatable mix of creative teams to work on this project, including – but not limited to – Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso, Dave Gibbons and Ryan Sook, Neil Gaiman and Mike Allred, Adam and Joe Kubert, Walt Simonson and Brian Stelfreeze, and more. It was an incredible collection of talent, and a grouping that only came together thanks to the man with the plan. In his mind, Chiarello knew that, “by working with the caliber of talent that I had, the end result would be ‘interesting’ at the least.” Check and check, I’d say.

The appeal to this project was varied. For a man with a mind for art history like Stelfreeze, he found it intriguing because artists “are kind of descendants of those guys that did the serials (on) Sundays.” For Palmiotti, he was excited to work with his wife Amanda Conner on something that was well outside of his safe zone, as they were telling a fun, all-ages story. Sook loved it all, noting the format, the character, 3 and his collaborator in Gibbons, “who is as much of a legend in comics as anyone has a right to be.”

“I can’t think of any aspect of the project that wasn’t appealing,” Sook said.

When it came to the characters involved, most were assigned by Chiarello. That wasn’t always the case, though.

“In a few cases, they asked for special, favorite heroes to write and draw,” Chiarello said. “When Neil Gaiman and Mike Allred said they were dying to do a Metamorpho story, it sort of made sense to me that they wanted to have fun with such an idiosyncratic character.”

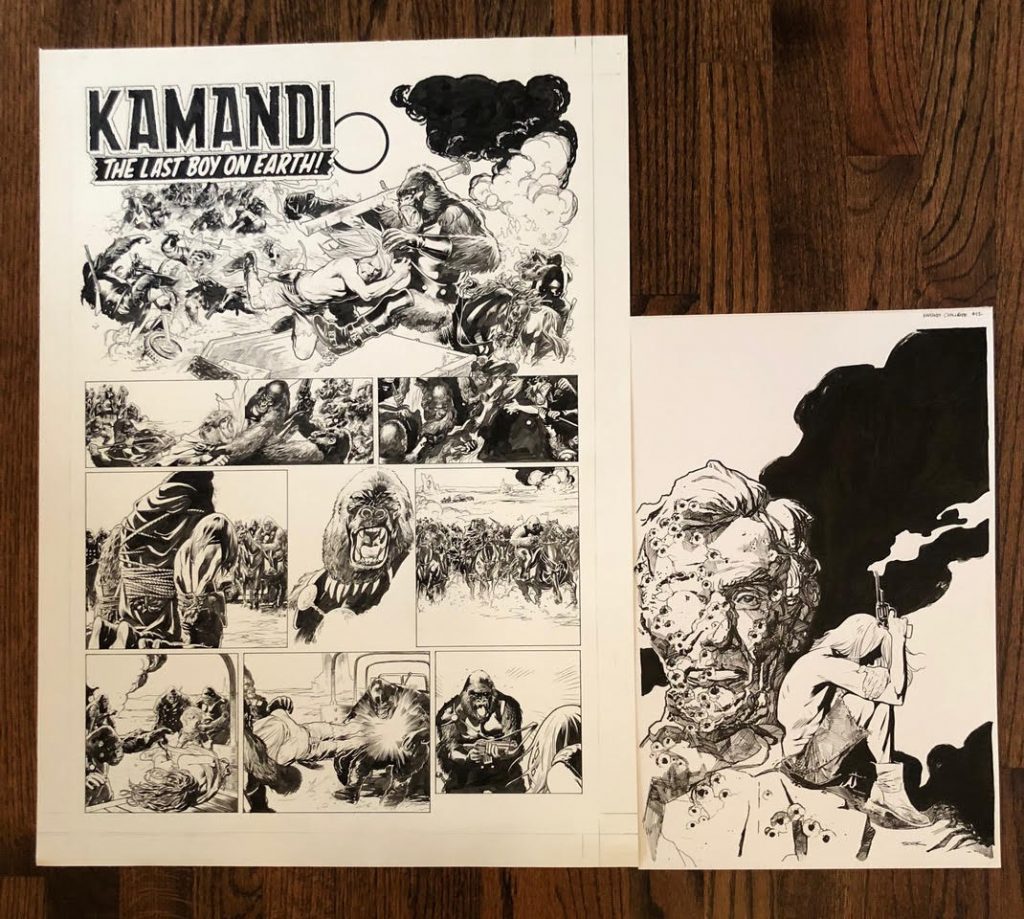

While the Trinity of Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman was well represented within the story, oddballs like Metamorpho, Deadman, Kamandi and The Demon (in a team-up with Catwoman, of all characters!) were as well, making this an exceptional tour of the DC Comics landscape. And with that, Wednesday Comics was set. Now, they just had to make it.

No pressure.

Making a comic with the names involved doesn’t sound like it would be much of a problem at all. Those are seasoned veterans guided by one of the brightest minds at DC Comics. What could challenge a crew like that?

“We had never published comics on such an enormous page before,” Chiarello shared. “They were even larger than DC’s ‘Limited Collectors’ Editions (aka Treasury Editions) from the 1970’s. Those were 14 inches tall, but we wanted Wednesday Comics to be 20 inches tall.”

Any time a comic publisher runs into something they had never done before, it’s going to complicate things. It was especially surprising considering DC’s longevity in the industry. If they hadn’t made a comic like this, no one had. Thankfully, as Chiarello noted, he had a heck of a team on his side to solve problems like this.

“Fortunately for me, DC’s Production Department is run by an incredibly talented gal named Alison Gill, who was up to my nutty challenge.”

While the production side was sorted, it also led to challenges for the creators. Some of it was simply size based. Chiarello told me that some of the artists would send him a look at pages as they were in progress to highlight the unique problems they were having to solve on this project.

“In many cases, the originals were so large that they dwarfed their drawing tables and hung over the edges!” Chiarello said. “Mike Allred brought one of them to a convention panel that we were on and the damn thing was as big as a movie poster!”

Typically, DC paper is 11 inches wide and 17 inches tall. But this was printing at 14”x20”, and to get the pages to look the way the artists wanted, that meant they’d have to work…a little bigger. This predictably led to some unique challenges.

“I worked at 18”x24”…well, a little bit less because the board was 18 x 24,” Quinones told me. “There was a funny thing actually…so early on the dimensions were different. And I think it actually printed at 16”x20”, and originally 18”x24”, so it’s just a little bit off. And when they made the change, I had already drawn two pages. So, to reformat, I would have had to clip off the sides of the page or add an extra panel on the bottom. And so I got away with adding an extra panel for I think page one, and then the next page, Mark was like, ‘No. It doesn’t work.’

“So, I had to cut off the sides and redraw the sides.”

“The boards were big enough that I had to custom cut them from huge sheets of special-order Bristol. They were so big, I brought in a piece of plywood to set on my drafting table so the pages wouldn’t overlap the edges,” Sook added. “And scanning the originals was also fun. At the time I had an 8.5”x11” scanner so I think it took six scans at least and quite a bit of Photoshop paste up to get each page prepped for color and print.

“I think back and I could have made it easier on myself. But the challenge was part of the fun.”

Stelfreeze was drawing at 13”x19”, and his biggest concern was related to the allure all of the space that size provided him.

“Because I was drawing it so big, the thing that I had to pay attention to is not get too deep into the details,” the Demon and Catwoman artist told me. “All of the classic stuff that we were drawing from is just really big and bold, so I wanted that to translate over.”

The legendary artist teamed with an equally legendary writer, and he knew they’d be simpatico from the jump. Within an hour of getting the assignment, Stelfeeze received a call from Simonson with just one question: “full script or Marvel style?” The artist leapt at the opportunity to work in the latter, as it’s his preferred method. He’s long had love for the old school style and believes that comics have suffered in recent years thanks to the full script format. This provided an opportunity to push against more modern storytelling sensibilities.

“Everyone’s thinking of the entire book as a story,” Stelfreeze said about today’s comics, before adding, “But back when I used to really get into comics as a kid, every page was a story.”

That’s exactly what they were trying to do in Wednesday Comics, as each page was designed to be a one-and-done story in a way while also feeding into a larger narrative.

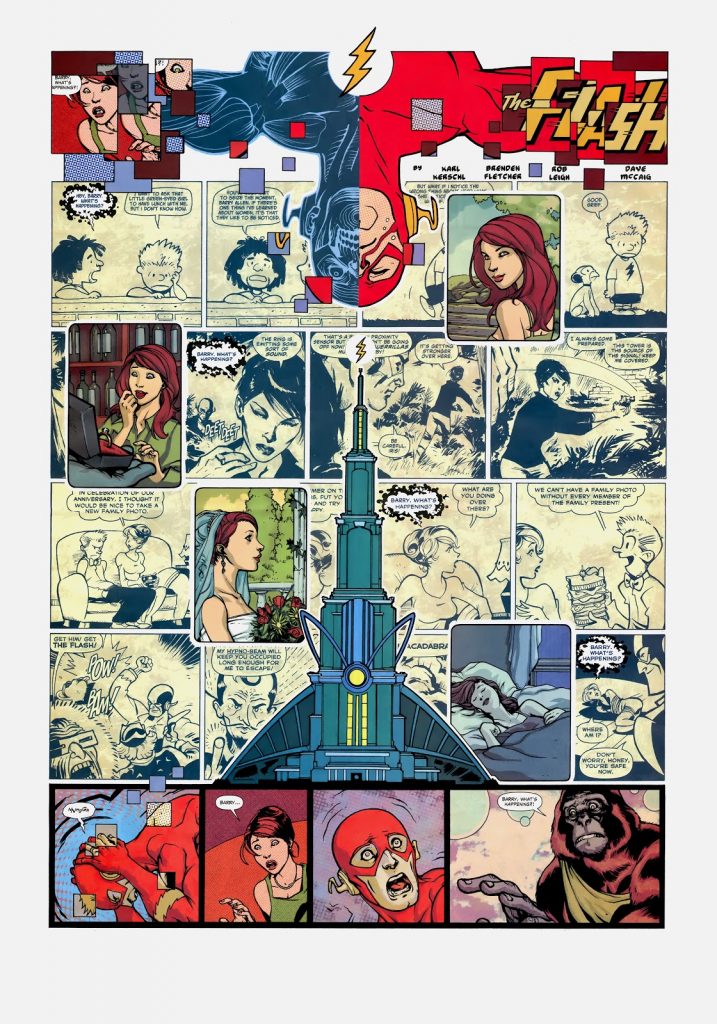

For Kerschl and Fletcher – an artist and writer duo who were creating their Flash tale together completely – their story was built around Barry Allen’s need to be present, wanting it to be less about super-villains and more about Barry’s relationship with his wife Iris through the prism of his super heroics. While the base idea was Kerschl’s, Fletcher figured out how to make it format wise. He suggested that they split their story into two strips on the page, with one tracking Barry and the other Iris before the two meet by the end. 4 That was a key to unlocking the greatness within this story, and for the two to feel good about making the whole thing work both as weekly strips but also as a larger story. That was a concern for the pair as they were making it.

“I think we felt pretty good about how it played weekly, but we weren’t certain how it was going to play as a complete piece when taken out of the context of the format and the distribution model,” Fletcher said.

Because of The Flash’s nature as a true science hero – he’s not just born of it; Barry Allen is a scientist himself – this led the pair down some rather atypical paths as they were brainstorming the story.

“It was sitting around breaking stories and just kind of nerding out over quantum physics, which is what we did for several months,” Kerschl said. “It was just electric. It’s just an amazing creative space to be in.”

“I’ve never done a thing where every week or something when we’re writing a script, part of what we’re trying to do is figure out a new science gag,” Fletcher added. “So we just have to keep reading science blogs and science news sites and just figuring out something that’s new and then figuring out a superhero gag to kind of tie into an actual piece of weird science.”

Fusing those ideas with the relationship between Iris and Barry was a challenge, but one that excited them even if they were uncertain about how effective it was while they were in the thick of it.

“The idea was tell a story about Barry’s relationship and how things don’t work for him unless he stops moving and stays present and focuses on things and do it in a way where we can play with quantum physics,” Kerschl said. “It was constantly interesting and bonkers. From week to week we’d read it and think to ourselves like, ‘This is insane. I don’t know how anyone’s going to follow this.’”

Figuring that out was a challenge for everyone involved, and while artists had the showier examples of the difficulties that came with the project, writers had important considerations to make as well. The ones I spoke to delighted in the opportunity.

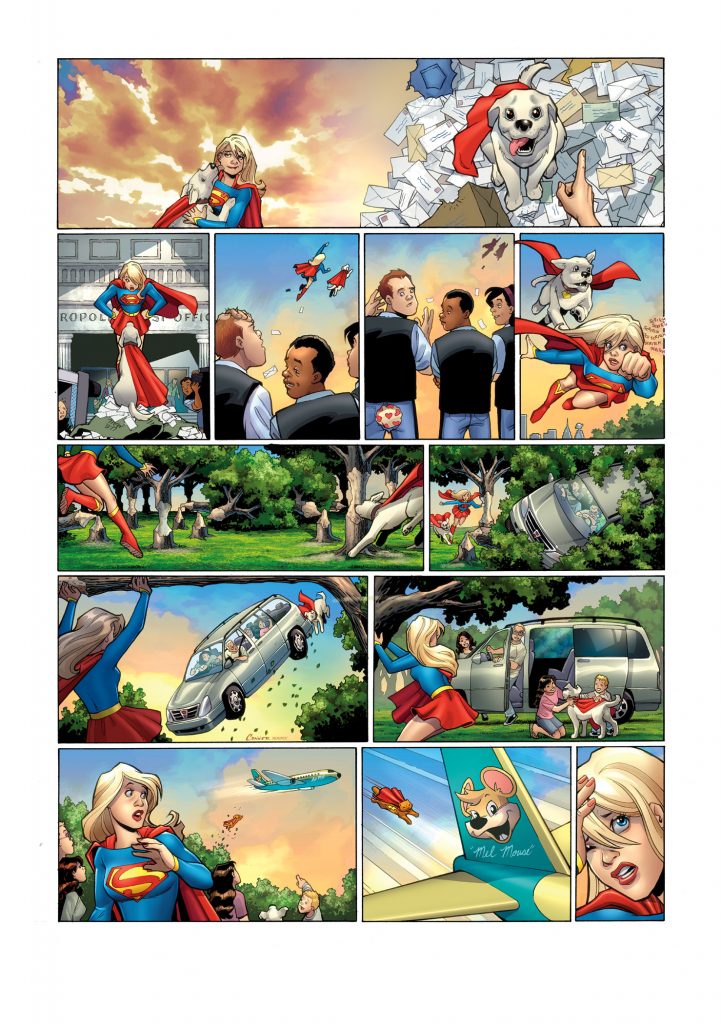

“My goal was to make this connecting story work as single page reads. If you came in on the fifth part and didn’t read the other four, it would still be amusing and all that,” Palmiotti said. “The good news was that the format made for more panels than a usual page and Amanda took it even further and did the pages twice up from the book size.”

“Every other strip had its own look and beat, and in the end, I think Amanda and I found ours and it was the start, for me, of figuring out how to work with my wife and understand what she really wanted to draw in comics,” he added. “You can see the love in every page, and no one draws a young girl and animals better than her.

“The whole project was a fun challenge for me.”

“It was challenging at times, but it was also fun,” Green Lantern writer Kurt Busiek told me. “I love classic comic strips, so the chance to dive into that paradigm and play with that form, rather than comic-book forms, was a real treat.”

Not everyone went completely in that direction, though. Caldwell’s Wonder Woman was an incredibly dense, gorgeous work, and one that was more serialized, although even then it was a bit of a remix from the way things usually work. He was creating a “more episodic story where each installment was not independent, but each one wasn’t an immediate continuation of the previous one for the most part.”

The beauty of this project, though, was the creators were given basically as much liberty as they wanted to solve these unique problems. As Chiarello told me, the creative teams “were given total freedom to have fun with the size of the page and the special challenges that came out of that and the weird task of telling a continuing story in one-page weekly installments.”

Caldwell said Chiarello’s message was “this is your baby, go for it,” and that when this “award winning, respected art director and amazing artist in his own right” “gives you carte blanche to do whatever you want, you run with that.”

“He didn’t edit anything,” Kerschl said. “We sent stuff in and I don’t think he ever asked for any changes.”

“There was definitely an air of autonomy where it’s not like, ‘You’re doing this, I think it’s this for you,’” Quinones said. “Of course, he’s an editor and he’ll tell you no if he thinks you’re wrong. But he also wants you to be happy and to be doing something you want to draw. And I think that’s part of it.

“It’s like he just wanted this to be fully a joyful experience for everyone.”

This freedom led to a diverse slate of comics, both tonally and character wise, with the stories filled with experimentation and occasionally mad ideas. One of the best examples was the ninth page of Kerschl and Fletcher’s The Flash story, a wild one that featured a variety of comic strip styles 5 and required “each tier to read horizontally in a correct way but also vertically in a correct way,” yet also diagonally at the same time while still working as a single page, Fletcher shared.

“It was days to write one page.”

“We had a whole map, a graph of how that had to be laid out to be legible,” Kerschl added. “And it’s insane.”

That was the kind of fun you were dealing with in Wednesday Comics. You could read a deeply serious, pulpy, very Azzarello and Risso Batman story, then turn the page and find Gibbons and Sook going buckwild with Kamandi. Things could get heavy, but you’d have the New Frontier-ish Green Lantern story from Quinones and Busiek or Palmiotti and Conner’s Supergirl comic to lighten the mood. It was a delicate balance, but one that was well met thanks to the efforts of the diligent editorial team led by Mark Chiarello 6 and the creators involved.

It wasn’t all roses, of course. Getting even a normal single issue together once a month can be a lot, but when you have a weekly series that featured upwards of 30 creators telling one-page stories in a never-before-used format, well…let’s just say that can become even more difficult. Part of that was resolved by lead time, as the creators I spoke to told me they had anywhere between four and nine months to work on each page, with Quinones suggesting he had a month for each of the 12 installments. Chiarello also planned ahead by having a couple backup stories together in case someone didn’t get their story in by the final deadline, 7 but that was a “break glass in case of emergency” solution. Caldwell almost drove him to use them.

“When the first page was due, I was already running behind. It was months and months before it was going to come out, but still, like I said, the man (Chiarello) had a deadline. First, I was sick, then I was traveling, and I thought I had sent them and gone through correctly and everything, but it hadn’t,” Caldwell said. “So, when I arrived at a friend’s house after traveling half a day, I had, like, 50 messages from Mark. ‘Hey, Ben, where’s the…?’ ‘Hey, Ben, are you sending…’ ‘Hey, Ben, why are you not answering me?’ ‘Ben, forget it. You’re fired.’ And then I couldn’t talk with him because it was the weekend, and I didn’t have his contact information.

“I finally got ahold of him and he had already made alternate plans with another creator because, like I said, the guy doesn’t have time to mess around, which I understood. I was sad, but since it was early enough, and since I was able to show him the page, and he knew all the work that was already ready to flow from that, instead of having a second person start from scratch he said, ‘All right, fine.’” Caldwell added. “But – and he looked me right in the eye, which is amazing because we were on a telephone, so I don’t know how he did it – but he looked me right in the eye and said, ‘This is not going to happen again.’ I didn’t sleep for nine months, but he got the rest of the pages.”

Chiarello remembers that as well, telling me he just thought Caldwell was nervous about being in a book with names like Kubert, Gibbons and Gaiman involved.

“He sort of shut down right at first and couldn’t deliver anything at all. I calmly talked him off the ledge, and I was then sure everything was going to be okay. But it wasn’t. He didn’t deliver anything for weeks; he just couldn’t unfreeze,” Chiarello shared. “So, I called him up and screamed at him and told him he was a piece of sh*t, 8 and that I’d see to it that he’d never work in the comics business ever again. He went dead silent on the other end of the phone and I told him I’d give him one last chance.

“The next day I received his first page and thereafter received the entire story on time.”

Chiarello was a master motivator, obviously, but per him, “it was all a bluff.”

“I tried the phony ‘scared-straight’ approach of being a monster,” he told me. “And it worked! SUCKER!”

When all was said and done, no one had been fired. But everyone involved had created varied, interesting work that rated anywhere from “worth a read” to “truly great.” The collective whole was a marvel, though, making for a deeply fascinating experience unlike anything else you could find in comics at the time, or really ever when it came to a traditionally direct market publisher. While its sales were never immense and it somehow was nominated for zero Eisner Awards the year it came out, 9 it did win the Best Graphic Novel Reprint award at the Eisners the next year. Beyond that, it’s become a cult favorite, a series where those who like it love it and those who own a copy revere it. How different it was played a huge part in that.

“Monthly comics, when done well, are like a great meal of steak and veggies. But Wednesday Comics was something special, something unusual, like a bonus, like a big piece of chocolate cake,” Chiarello said. “You can’t – and shouldn’t – eat chocolate cake for every meal. But once in a while, that special treat is welcomed.”

It truly was a treat, but the process took a lot out of Chiarello and others involved. Managing all of those creators and the production as a whole was a taxing process, and it led to the man behind it swearing he’d never do it again. Or at least he did at first.

“Then, of course, five or six years later, the bosses at DC asked me to do a sequel,” Chiarello told me. “I started to get jazzed about the possibility, but they wanted it to be created as a digital, online strip. I sorta scratched my head over the logic of that, since the charm of Wednesday Comics was holding those enormous pages in your hands. That experience would have been lost on your computer, no?

“So, in the end, I begged off.”

But for those who worked on it and those who read it, it’s something they remember as a special work. For Stelfeeze, he thought a lot of it came from the distinct voices on the title.

“When that first issue came out, it was like, ‘Well, none of these guys are on the same planet,’” Stelfreeze said. “I mean, everything looked so dramatically different. And that was one of the things that I enjoyed most about it, was that not only was I a part of (it), I was geeking out on the project every week it came out.”

Beyond that, having so many luminaries on the project fueled a competitive spirit amongst creators. Stelfreeze suggested that everyone knew they might not be the top person on the book with the massive names who worked on it, but no one wanted to finish last so they worked hard to ensure that they didn’t. Kerschl and Fletcher have seen a whole lot of the hardcover collection of this series at cons, and they insisted that every person who had it signed shared it was “their favorite thing ever,” with Fletcher believing a reason for that stemmed from the creators pushing themselves, almost as Stelfreeze suggested.

“I think that every team that was working on that series was trying to tell a story that somehow touched on the most iconic elements of those characters in a very small space, in a format that felt fun,” Fletcher said.

Sook saw it as something that “connected the modern sensibilities and characters to a form of comics storytelling that had been so outdated for so long.”

“Bringing the contemporary approach to a nostalgic format really lets the audience experience that tethering together of the history and the present in a truly unique way,” the artist added. “That’s what makes it a special project, I think.”

In Stelfeeze’s mind, though, what really made it special “was the moment.”

“Oftentimes you have those projects that happen and it’s a good project, but it’s a good project in the right moment for it,” Stelfeeze told me. “And I remember things like, you know, Mike Mignola’s Gotham by Gaslight. The Killing Joke. Those stories are not only great stories and great art and everything, but they happened at the perfect time.

“And I think Wednesday Comics is one of those things that it seemed like the industry cleared a space for it, and it just landed right at the perfect time.”

It’s a project everyone looks back fondly on for a number of reasons. For Fletcher, he was ready to be done with comics, but Wednesday Comics eventually opened the door for him to become a full-time comic writer. Quinones went from someone stuck as a “young readers guy” 10 to someone who will never need to look for a gig for the rest of his career on the strength of his work within. It changed the perception of Palmiotti’s writing, arguably even setting he and Conner on a path towards helping redefine Harley Quinn in the process.

Caldwell said that he didn’t sleep for about nine months during the process of making the series, but it was “an amazing opportunity” for him because of the freedom and creative passion of everyone involved.

“You’re creating meaning out of a lump of paper, shapes and colors. To be able to invest some crazy idea in your head with meaning and have even some fraction of that meaning translate to other people and resonate with other people is such a surreal and human thing,” Caldwell said. “I really loved that. That was definitely for me one of the projects that I feel that I got closest to that experience.”

In the end, though, all of these great comics and incredible opportunities wouldn’t have been possible without one man: Mark Chiarello.

“Mark had a great idea, sold DC on it, and then recruited the best and supported them in realizing their vision, however traditional or experimental it might be,” Busiek added. “That’s a triple-threat editor.”

Quinones believed the mix of creators only happened because of Chiarello’s efforts. He viewed the project’s editor as the foundational element of Wednesday Comics. 11

“He just knew what would work and had this rapport with all these different creative teams and I don’t think anyone else could have assembled that grouping of artists, those unique pairs of writer and artists per story,” Quinones said. “I feel like you could easily have teams that might feel a little too close to each other and then, in a subconscious way, a reader might get bored.

“And I don’t think that happened. I think there’s such a breadth to it, and that is owed entirely to Mark.”

The man behind it all, the one who helped foster some of the finest works of DC’s past few decades, is no longer with the publisher. Mark Chiarello was laid off as DC’s Senior VP Art Director this year as part of “organizational changes” after 26 years of exceptional work, leading to an outpouring of support that spoke to the love and respect he engenders from the comic book community. It wouldn’t have been surprising for Chiarello to have mixed emotions about the project, if only by association. That wasn’t the case when it comes to one of the most beloved projects from his tenure there.

“Some days, we all just go to our jobs and try to do our best. Corporate interference and inept management and a million meetings often tend to wear you down and stand in the way of what you were actually hired to do,” Chiarello said. “But once in a while, you can fool ‘em all and do something that you know is good, something that you can be proud of for the rest of your life.

“For me, that was Wednesday Comics.”

Thanks to Chiarello, Busiek, Caldwell, Fletcher, Kerschl, Palmiotti, Sook, Stelfreeze and Quinones for the perspective on this great project.

Additional note: there are many examples of comics from the usual methods that are legendary as well, but I’d wager that the hit ratio for that method is lower than you’d see with the riskier endeavors.↩

It was the offseason.↩

Kamandi.↩

The pair emphasized that both colorist Dave McCaig and letterer Rob Leigh were paramount to making that split work, with coloring and lettering choices distinguishing each strip.↩

For example, the page was drawn in not just the style of their strip, but also in the art style of Dick Tracy, Modesty Blaise, Blondie and others.↩

Assisted by now big time DC Black Label editor Chris Conroy!↩

Those were a Plastic Man story by Evan Dorkin and Stephen DeStefano and a Beware the Creeper one by Keith Giffen and Eric Canete, both of which were in the final collection.↩

Editor’s note: His edit, not mine.↩

Every judge from that year has been retroactively fired.↩

My quotes, not his.↩

Everyone else agreed with this point as well.↩