The Perceptions and Realities of the Artist Credit Movement

In recent years, every day brings a different subject for the comics internet to debate. While topics come and go, the important ones – like diversity or women’s rights in comics – transcend the quick rise and fall most follow on the internet. They may not be omnipresent but they return when necessary.

Lately, the conversation has centered one of those recurring topics. It’s an element I’ve been looking at since I started writing about comics: the importance of fair credit and proper attention to artists. It’s a topic that has been tackled here many times over, and with good reason. It’s a conversation of value that has already led to progress.

Recently, however, there’s been a shift. It felt for a while the discussion was building to something greater. A tipping point that could lead to positive change for artists. Instead, the topic has become something of a point of paranoia for some and shifted to be a divide between writers and artists for others. For every reasoned thinker in the discussion such as comic artist Declan Shalvey or children’s book artist Sarah McIntyre, there are others who take the slightest bit of information and let it fuel their darkest thoughts. I saw it first hand in the response to my retailer survey. One chart of its 18 spread amongst the art community like a veritable forest fire. It generated sky is falling thinking along the way without many knowing the chart was referencing retailers, not readers. Like with everything, context is key. Minus that, things can get dark quick.

So there’s good and bad that comes from this discussion. However, one of its biggest issues is somewhere along the way the perception of what is happening became ever so slightly different than reality. That can happen with anything and is often a product of the conversation happening on social media. Reality is much more complex than perceptions, though, and nuance can get lost the wider discourse gets. Today, that’s what we’ll look into as we explore the realities of this important conversation.

Perception: There is a versus between the words “writers” and “artists”

Reality: Writers are partners, collaborators and often friends of artists – not the enemy

The strangest part of the artist credit conversation has been the divide of sorts formed between writers and artists. You’ll see that pop up on social media. It can feel like the telephone game has been introduced to the discussion. As a message gets passed further along the line, the content degrades and morphs into something else. It goes from “artists deserve more credit for the work they do” to the natural flip side: writers deserve less credit. But that’s not what it has ever been about, really.

“For me, this has NEVER been a ‘writer vs artist’ thing,” said Shalvey, the artist and co-creator of Injection at Image. “It’s about creators co-authoring a piece of work and being credited appropriately.”

At its purest form, that’s the issue. And beyond a few exceptions, writers aren’t a problem for artists. Most writers value artists as not just their lackeys; they are partners, collaborators and friends. Matt Fraction wrote a piece on the subject, and it gives insight into the way one writer looks at the creation of comics.

“I write for my partners. I write with them and to them. I seek collaborators and co-conspirators rather than employees. I share ownership of the books I do (HAWKEYE obviously an exception) with the artists for whom I write as a rule. They make more than me, too, as a rule, and they earn it. Comics are a visual medium; to quote Mark Twain, ‘Thunder is impressive; but it is lightning that does the job.'”

That’s not just Fraction talking to talk, either. The people who work with him feel the same way. When I asked David Aja—Fraction’s collaborator on Hawkeye—about his teammate, he said, “Matt is my partner, my friend and he has always had (nothing) but love for me. Requited love. Matt, if you are reading this, you know I love you.”

Other artists shared how meaningful having a supportive collaborator can be. Greg Hinkle, who works with James Robinson on Airboy, said Robinson has had his back in both public and private, and that has meant a lot to him. “Working in isolation for long periods of time is hard, but knowing that my partner is looking out for me while I’m alone in my drawing hole takes some of the pressure off.”

Leila del Duca, who co-created Shutter with writer Joe Keatinge, found similar value in her collaborator’s support – especially after going through mixed experiences in the past.

“Having a collaborator like Joe has meant more than I can even accurately express,” she said. “I went from a job that didn’t trust my input or want my true style, to working with an incredibly imaginative writer who asked me what I wanted to draw, and delivered, AND encouraged the storytelling changes I believed in, who expressed his excitement every time I sent him new artwork.”

She added that Joe has went out of his way to include her in every press engagement and panel discussion about the book, which has helped as well. “Without Joe’s efforts in getting my name out there, I adamantly believe that far less people would have paid attention to who I am and what my art’s all about.”

That’s not how all partnerships go, of course. You hear stories of creators wrestling over credit or money. In the artist survey I ran, more than half of participating artists reported experiences of working with untrustworthy collaborators. It happens, and not just to artists.

All of this isn’t to say writers don’t get more credit than artists. They do in most cases, and it is often easy to explain why. There are five main reasons writers have taken up the dominant role in comics, and it has little to do with choice and more to do with a variety of other factors inherent to comics and society.

Volume

“Drawing comics is a much more profoundly greater physical labor than writing comics,” shared Charlie Chu, a Senior Editor at Oni Press who works on books like The Sixth Gun and Kaijumax. “Writers in comics – specifically mainstream, floppy books – can juggle anywhere around five titles at a time on a monthly basis, when most artists are barely able to illustrate one at a time, so the value and branding ascribed between a writer and artist is unfairly weighted.”

He’s right. The frequency someone’s work comes up plays a huge part in the attention they get, and that happens in all fields. But in comics, the disparity of work can spider into how attention is divied, as Dark Horse Comics Editor-in-Chief Scott Allie added.

“I think what’s driven it is that writers can write three or four or fifteen books a month, whereas artists can usually only do one,” he shared. “That means press is eager to talk to writers about all their books, publishers are eager to promote writers because that might mean promoting multiple books.”

Longevity

Brian Michael Bendis’ Guardians of the Galaxy.

Qualifying a book as such would grate at even the most forgiving artist. It’s hard to blame them. It was more than just Bendis. He would be the first person to say that. But as Patrick Brower of Challengers Comics + Conversation in Chicago shared, “in the span of that book’s 28-issue run, it had 9 interior artists, not counting the several oversized issues with multiple stories in them.”

For fans, retailers and the press, it isn’t out of malice this volume of Guardians is referred to as the Bendis run. It’s out of expedience. It’s difficult to refer to it as Bendis, McNiven, Pichelli, Francavilla, Maguire, Marquez, Bradshaw, McGuinness, Schiti and Lopez’s Guardians of the Galaxy. Those are huge names of the comic art world, and they’re changed out at a stunning rate. The longevity writers have on titles and the way artists shift from title to title for small runs at a time plays a huge part in the relative value writers have over artists. It makes using a writer’s name instead of the writer and artists’ names shorthand for those talking about a run.

Attribution

Anyone can look at a comic and decide the basic things a creator did. The writer wrote the script and the plot. The penciller made the pictures happen. The colorist made the comics all rich and colorful. It goes on and on. But the struggle with attribution lies in the murky middle ground between all of that. Sadly, the tie often goes to the writer. People describe “story” as something the writer does on their own, but artists of all varieties are storytellers in their own right. Sometimes their contributions can be more difficult to diagnose.

As Chu shared, “I think in large part it comes from a couple of misconceptions about the collaborative process in comics,” and he’s right. Like in film where people match almost every creative decision to the director, much of the reason writers get more credit is because the indistinguishable aspects of a comic are put into the writer’s ledger, for better or worse.

Promotion

I’ve been writing about comics for six years now. In that span the amount of artists who have emailed me to promote their work could be counted with just my two hands. Writers? Hundreds.

That’s a simple by-product of availability. Writers often take the lead on promotion of a book because artists spend an obscene amount of time drawing. It’s a natural fit and at least part of why they get more attention, as colorist Matt Battaglia wrote about recently. It’s who people know because they are the face of the book for most.

“Writers being able to juggle multiple projects means they can spend their time on social media and self-promote WAY more than most artists can, and most artists are investing their time and energy actually drawing comics,” Chu said. “It’s kind of a negative feedback loop where it can devalue the hard work that artists do.”

Chu believes artists can help themselves in this regard, but it takes a different mindset.

“Hopefully this current conversation about credit and authorship for comics from a marketing and sales perspective makes it clear to artists – especially those working on creator-owned books – how important it is to self-promote and brand the same way writers do.”

Plot Driven Society

When Lost was in its prime, many of its fans spent more time researching the mythology and random imagery within the show than they did watching it. The blast door map, anyone? It’s because as a society, we often think in terms of plot. Who are the keepers of the plot in comics? Writers. They’re the ones who know what Batman will do next, and we always want to know about that more than how he did what he already had. It’s a weird tenet of humanity, but it’s yet another thing that makes writers more central to the comics conversation.

Perception: Writers and Artists make comics as separate entities

Reality: A creative team makes comics together

Many look at writers and artists as these islands that are together but separate. They work on the same project, but not as one. But to achieve something great it requires more. Chu knows what it takes. It takes true collaboration.

“Artists are fundamental to making comics. I always bristle dealing with writers or other people in the industry who think of artists as collaborators who are there to execute a vision or a plan, when really, these things are creative marriages where the lines of demarcation are and should always be blurry,” he said.

“The best projects are ones where you aren’t working with a team that’s assembled the way you order things on a menu, but everyone should feel like they’re part of a gang that’s working towards a great whole.”

Image Comics Publisher Eric Stephenson seconded that thought, as he said that’s how greatness is accomplished in the art form.

“Short of a writer/artist doing everything him or herself, all the best comics are the result of great writer/artist teams working together, whether you’re talking Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in the 1960s or Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples today,” said Stephenson.

When you think of the best comics made by multiple contributors, odds are, most of them weren’t made like Ford makes trucks. They work together. It takes a team to create the works we love. A great example is the just completed volume of Hawkeye. Aja shared what creating that book was like in great detail, and after you read it, you will know there is no way this book would have reached the heights it did if they didn’t work as a team.

“As usual with Matt, I cannot say who started this. I think I made some comments on Hawkeye back in the day when we finished Iron Fist. Years later, he went to Marvel with a pitch for me to draw, but it was actually something different from what we did. It was some more of a spy thing. We started talking. I did not like James Bond but I did like Lalo Schifrin, so I did the design elements and he plotted a story of a guy saving a dog. Sounds crazy? Well, that’s exactly how Matt and I work together.”

“As I said, it is hard for us to know who came up with what idea. It could be a joke, a song, a sketch…that jumps to another stuff and to another. We actually decided to sign ‘by’ instead of ‘writer-artist’ for that reason.”

“After our regular bullshit talking, Matt writes a plot. I start sketching and ‘having ideas.’ I’m pretty sure both Matt and Steve Wacker (our editor) cursed at every mail of me that started with, ‘hey, I’ve had an idea.’ I do sketches, share ideas, Matt writes more stuff, keep on sketching, Matt keeps on writing, more sketches, Matt writes dialogue, I do pencils, Matt rewrites dialogue, I write dialogue…well, my dialogue was crap, Matt, please, rewrite it, and on and on until inks are finished.”

“Then I do same with Matt Hollingsworth on colors, talking talking, emails emails. Yup, I’m a guy who talks a lot, right.”

“And finally the same with letterer Chris Eliopoulos. Matt has written all the dialogue and I have been doing a not-final/clumsy lettering that I pass to Chris, and I swear, both Matt and I are picking around, changing stuff, tweaking here, Matt writing new things, cutting words…and so on until the minute before the comic goes to print.”

“Matt, Matt, Chris (and Steve and Sana – the editors) and I are a team. We all have been working together, and Hawkeye is our work. We all have done it, with Annie and Javier…and the rest of guys helping us on single issues, of course.”

~ David Aja

That’s a comic published by Marvel going through a process like that. It’s incredible. As much as everyone may treat them as separate entities, it really is a team behind the best comics. Not only that, but it is never as simple as “Matt writes and David draws.” A comic in some ways is a living thing, and only together can creators make a book truly thrive.

Perception: Retailers favor writers over artists when it comes to ordering

Reality: Retailers factor everything in when they are deciding what to order

This was hardly an issue before my recent retailer survey and the infamous chart that spread throughout the comics internet. Retailers drew the ire of many on social media, and that isn’t fair. It was the restrictions of the question – which asked them to pick one aspect of a comic to order from – that put them in a position to play the villain.

In reality they look at everything when deciding orders, but some aspects play a bigger part.

“Simply put, I look at everything. Publisher, character(s), writer, artist, issue number and price,” said Brower. “Each of those things matter differently on a case-by-case basis, but hands down the most important element I look at when ordering comics, is how the previous issue sold.”

Matthew Klokel of Fantom Comics in Washington DC shared the formula he follows for ordering to give you insight into how they work.

“If we’re ordering a second issue of a series and have no first issue sales history yet, then the formula is: (copies ordered of #1) * (0.75). We smudge this depending on subscriber interest. If we have a high level of subscribers then we go closer to 1:1, if we have hardly any or none at all it might drop down a lot further.”

“We’ve found that after you pass the first story arc people who want to read the monthlies are already subscribed; people who get into the series after that point either stick to the trades or become subscribers,” Klokel added.

For new titles, an array of aspects are factored in. Buzz both online and in-store, the creative teams and how cool the story sounds are important. However, Klokel said for smaller books the level of his staff’s excitement plays an even bigger part. If his team is excited, it’s easier for them to sell the book. Brower said it’s on a case-by-case basis. Depending on the title, the publisher, creative team, price and other aspects can carry the most weight.

When asked whether artists matter when ordering, Brower and Klokel had differing perspectives. Brower said it depends on the book and the artist. For Guardians, “that book continued to sell regardless of who was drawing it, so I stopped even taking that into consideration.” He said if Sean Murphy was drawing the book, he’d order bigger because his name sells. For creator-owned, artists are an even bigger factor for them. However, he was careful to say this isn’t the case for every shop.

“You have to understand that LESS THAN HALF of the comic book retailers in the United States order anything other than mainstream comics for their stores.”

While Klokel said writers are more important in terms of demand of books in his shop, he did share a fascinating anecdote: “I will say that for in-store signings the formula is reversed. People want to meet artists; get their books signed by artists; get sketches by artists. Unless you’re a really famous writer, artists are more in demand in person.”

The reality is no retailer will go into the ordering process and base their numbers off of one factor. Every aspect matters. It just depends on the situation. Thankfully, they don’t have to pick one aspect to decide off of.

Perception: Fans care much more about writers than they do artists

Reality: Every fan is different and purchases comics for their own reasons

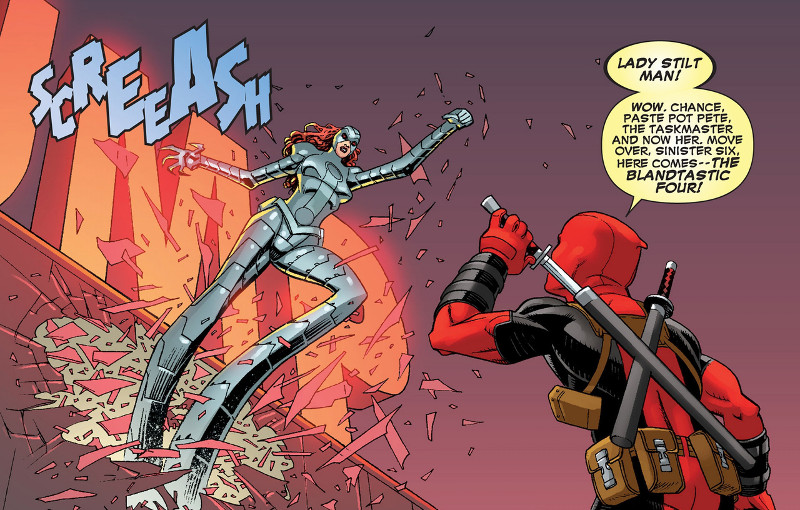

This is the simplest part to explain. Fans care. Artists are a huge part of the medium we love. But every fan is different. Many favor writers. Some favor artists. Some prefer quality paper stocks and left handed characters. Others exclusively collect comics starring Lady Stilt Man. I’m not here to judge. Ultimately, a team makes the comics we love, and for the most part, fans value one element above any creator or character: the comic they produce together.

Perception: Publishers treat artists as disposable, secondary creators

Reality: Some Publishers treat artists as disposable secondary creators

This is the biggest problem for artists, in my mind. In today’s era of double shipping and reboots – which isn’t subsiding anytime soon – artists are more fungible than ever. Marvel rotates art teams to a stunning degree and those actions contribute a great deal to devaluing their work in the eyes of Stephenson.

“Generally speaking, I think it is due to the practices of other publishers that don’t place much value on consistency in terms of art,” he said. “There are series where the artist changes every few issues in an effort to keep the books coming out on time, but the long-term effect of that has been to reduce the importance of any one artist’s contribution to the book in question.”

While he wasn’t only speaking of Marvel – other publishers do what he’s talking about – it’s difficult to look at other moves Marvel has made and not think of them first. Beyond double shipping, in their recent All-New All-Different line announcement, Marvel omitted artist names from several titles. That’s problematic in its own right.

Meanwhile, DC has emphasized name writers over name artists, in Brower’s mind.

“Can you name 10 DC A-list artists currently working on DC projects? And by ‘A-List’ I mean people that move the sales needle,” he said. “I should be able to — it’s my job – but I can’t.”

While he admits someone like Babs Tarr is a selling point, he shared she’s the exception, not the rule.

It’s not just the big names doing it, though. AfterShock Comics caught flak for unveiling their launch line-up with writers attached but no artists. These examples may not seem like that big of a deal by themselves. But when they keep happening, a mentality is created. Take this tweet from Jennifer de Guzman, the former Director of Trade Book Sales at Image, for example.

@royalboiler There are a number of people who didn’t understand why Saga doesn’t have a fill-in artist instead of breaks between arcs.

— Magister Jennifer (@Jennifer_deG) February 12, 2014

That’s Saga, one of the most beloved and successful books in comics. Some are curious why there aren’t just fill-in artists instead of Fiona Staples having a break to recuperate and get ahead on the next arc. That’s shocking. If the mentality publishers create in readers is so great they’d act that way towards a book like Saga, what hope do artists on smaller books have?

That’s not to say every publisher treats artists in such a way. Chu values artists like he does all of the creatives that work on his books, and he shared that is derived from the top at Oni. That value goes into every one of their comics. Stephenson stressed that artists are as important to Image as writers. Allie finds artist contributions to be invaluable to what both he and Dark Horse does.

“The artists are essential, obviously. The artists provide such a major part of the experience of reading a comic that it can’t be discounted,” he said. Allie cited the cases of putting Fight Club 2 and Umbrella Academy together, saying it was important to get artists who could match the quality the very famous writers on those projects.

“I wasn’t going to throw someone onto those books who could get it done fast and cheap, knowing that I could sell it on the strength of the writer’s name. In both cases, we got the best possible artist for the job, who elevated the work of the writer,” he said. “That should always be the goal. Because the artist is of course that important.”

Like with people, there are plenty of variables for every publisher. Not every one of them will act the same way. While a few treat artists as interchangeable, not every publisher does. That is important to remember.

Perception: The media focuses on writers because that’s what they know and prefer

Reality: While they could do better, the media does focus on writers but not for that reason

Yes, writers do get the focus of the media. But as explained above, there are reasons for that. The mere fact writers have more time and tend to be more self-promoting helps, but reader’s interest in plot and the difficulty in attributing who did what plays a key role as well. As shared in the Guardians example, sometimes writers are just used as shorthand because it’s the only viable option at times. For most of the press, it is hardly done out of spite.

That doesn’t let everyone off the hook, though. Many sites omit artists from articles without any real thought, which is a shame. While it doesn’t happen to him often anymore, Shalvey said he would see that happen from time-to-time in the past.

“On Thunderbolts, I came on the book when Jeff Parker and Kev Walker were the established creative team. I started out on fill-in issues for the book, then worked my way up to co-artist as Kev and I would draw alternating arcs. Often though, I would be unmentioned,” he said. “I have to credit Jeff Parker for always dropping my name in interviews. Meant a lot to me at a time I was really trying to get my name out there.”

That’s another example of why it’s important everyone on a creative team has each other’s back. And as tough as it can be to decide who does what in a book, writer Kieron Gillen had a great suggestion a few years ago for reviewers struggling with the attribution issue.

“The Writer/Artist team is basically a faux-cartoonist, two people trying to work in harmony to do the job which abstractly could be done by one,” he said. “Point being: since they’re attempting to become a faux-cartoonist for the space of the work, maybe it could be interesting to treat them as a faux-cartoonist and consider all their work together as a single entity.”

It’s a great idea, and one I have tried to integrate into my reviews as much as possible. This could help reduce the attribution issues by looking at the creative team holistically. It may be difficult to use at times, but it can be very effective.

Beyond attribution, problems will still come up. Some are out of the control of the media and others aren’t. An example of the former is when publishers leave artists off of press releases or promotional materials like the All-New All-Different preview book. While publishers may not view that as a big deal, it creates the subliminal message to the press that artists are less valuable.

Worse still is when sites go out of their way to not feature the artist. Recently, an artist conveyed a story of an interview they had done with one of the biggest comic sites. Along with the writer, they teamed up for a chat to showcase their book. When the piece was published, all of the parts from the artist were omitted because of issues of space. That wastes the artist’s time, which is a precious commodity. It’s also a shame things like this happen because of something Shalvey said.

“Comics are more and more attributed as a creation of the writer, not the writer and artist,” he said. “When all the headlines mention a book as belonging to the writer, it perpetuates that perception repeatedly. The artist isn’t seen as co-author of the book, he/she is seen as the person who happens to be drawing it.”

Part of that comes from a point Chu made – “(in) an industry where the majority of comics journalists are aspiring writers, a lot of the conversation can be super writer-centric” – but there are examples where artists are featured well. The AV Club’s Oliver Sava does a great job of this in pieces like his talk with Kris Anka, Sophie Campbell and Ming Doyle about the importance of costume design in comics. My former home Multiversity Comics goes out of its way to feature artists in reviews. Editor Mike Romeo even developed an in-house guide that was turned into an article for the masses. There are other great examples out there, too. As with anything, the press could do better. But they’re progressing.

Perception: Artists deserve more credit

Reality: Artists do deserve more credit

“Drawing comics is hard. It’s long hours of huge workloads over months and years,” said Shalvey. “It’s my dream job and I love it, but doing something just for the love of it is why so many artists are taken advantage of, become burnt out early and facing crazy medical bills in later years. It is actually physically grueling over time, and like pro athletes, we only have a certain amount of commercially productive years in us. Not getting properly credited for the work done is why artists end up penniless while the characters they created rake in millions at the box office.”

“Equal credit for artists means that they can reap ALL the benefits from their hard work, not just accept the paychecks for work provided.”

What Shalvey said is why this topic is so important. Regardless of the hubbub and how off point the conversation can get, one aspect has always remained true: artists deserve more credit. And it impacts them in more ways than just seeing their names in an article.

The biggest problem is it is a top down issue. The names at the top of the industry are in the business of making money above all else. All businesses are, really. To make more money, they maximized the product released both in volume and in frequency. As someone who toiled at business school for years, I understand. It’s even a reasonable assertion given how changes like double shipping have impacted bottom lines. But someone has to take the hit for substantive changes to comic policies and procedures, and so far it has been the artists who work on the books. There is just no way any artists can keep up with such a schedule, short of developing a debilitating addiction to performance enhancing drugs or Turkish coffee. And it rolls downhill.

If a publisher doesn’t consider artists valuable enough to make them a staple of a title, then how can retailers order based off them? And how can fans think of a run as anything but the writer’s if there were nine artists in a 28-issue span but one writer? And for the media, what are they supposed to do with press materials touting the writer but not the artist?

As much as this has become a writer versus artist thing, in my mind, it’s never been that. It’s an issue of industry trends turning artists into fungible pieces of the art form. That dam has been broken, and there isn’t much we can do about it. Comic sales are at a 20-year high, so these methods aren’t going anywhere.

What we can do is focus on the comics where the time and craft of a creative team is valued, and where that value turns into high quality comics. We’re seeing that more than ever today. Books like Jillian and Mariko Tamaki’s This One Summer. Greg Rucka and Michael Lark’s Lazarus. Noelle Stevenson, Grace Ellis, Shannon Watters and Brooke Allen’s Lumberjanes. Upcoming titles like Paper Girls from Brian K. Vaughan, Cliff Chiang and Matt Wilson or The Nameless City from Faith Erin Hicks and Jordie Bellaire. There is something that can be done about them.

We can preorder. We can talk about these books with whoever will listen. We can sing from the rooftops in praise of the people – all of them – who make the comics we love. Artists can get the credit they deserve if we want them to. It’s up to us. All of us. We just have to choose to make a change, and we have to choose to do it together.

Thanks to David Aja, Scott Allie, Patrick Brower, Charlie Chu, Leila del Duca, Greg Hinkle, Matt Klokel, Declan Shalvey and Eric Stephenson for talking with me for this piece. Marvel politely declined comment for this piece, while DC never responded. Header image is from Hawkeye #1 with art by David Aja and Matt Hollingsworth.