SKTCHD Survey: What’s the Life of a Comic Artist Like?

The results of our first annual comic artist survey are revealed

What’s the life of a comic artist like?

It’s a good question, and one many — including Brian Churilla very recently and yours truly — have explored in the past. But one thing often forgotten when trying to answer that question is comic artists are more things than they’ve ever been before. They’re not just men who work on floppies for Marvel or DC, but many other things as well. Few roles in comics show off the diversity we all want for comics better than the pencillers, inkers, colorists, flatters and letterers in today’s industry.

But with such a sprawling collection of people creating comics today, how can one hope to represent a greater whole? The simple answer is you can’t. All you can really do is try and reach the most artists you can, which is what I did with the first annual SKTCHD Comic Artist Survey. Over the past month, 186 artists anonymously responded to questions about who they are, what they do, how much they earn, which publishers they had the best experiences with, and much more in an attempt to provide a clearer picture as to what their lives are like.

The plan for this project is to bring it back each year to deliver an evolving view of how artists live and how things are changing for them in this time of industry boom, while refining it as years pass. It starts with this first survey, though. The hope is an effort like this might give publishers, writers, readers, reviewers and up-and-coming artists a more comprehensive view of a world they may not fully understand. In the process, we might even answer that question asked at the open of this piece.

A Caveat

One thing to consider when looking over all of this data is it isn’t perfect. While 186 respondents is a lot, it’s not statistically significant and not everyone is the same, nor did everyone respond to every question. Within each question, some parts may have only applied to certain respondents. What that means is with many of these, we’re talking about a fraction of a fraction of the overall whole. This by no means is meant to be a definitive look at what the life of every comic artist is like. What it is supposed to be is a snapshot of the comic art world today, and the good and bad that comes with that. Please keep this in mind when you read through the results.

The Respondents

Before we get into the juicy stuff, it’s important to share the profile of those who responded. While these questions and answers don’t tell us anything revolutionary themselves, they provide important context for the rest of the results you’ll see.

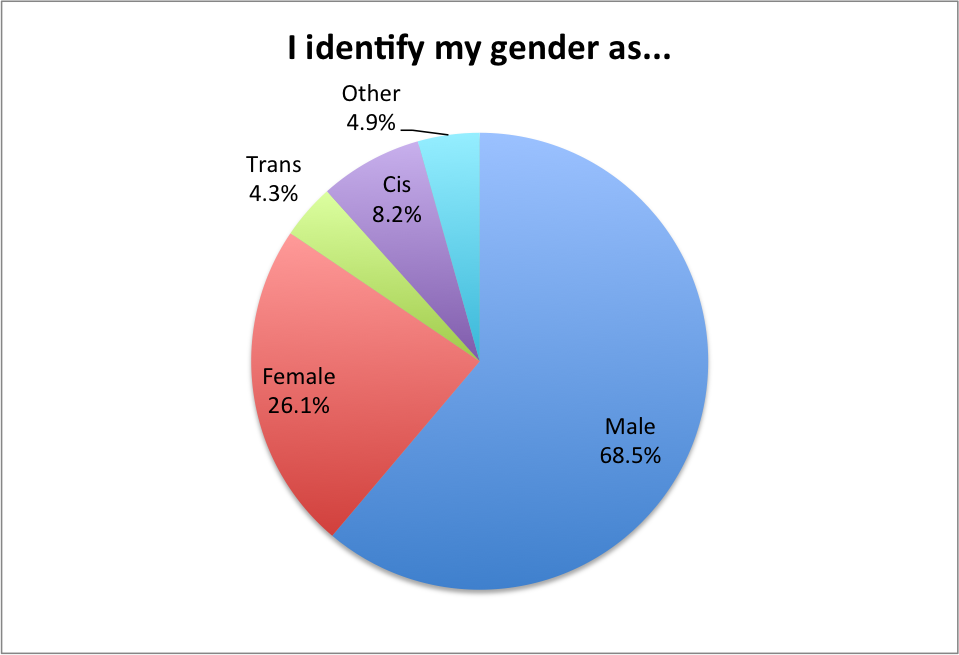

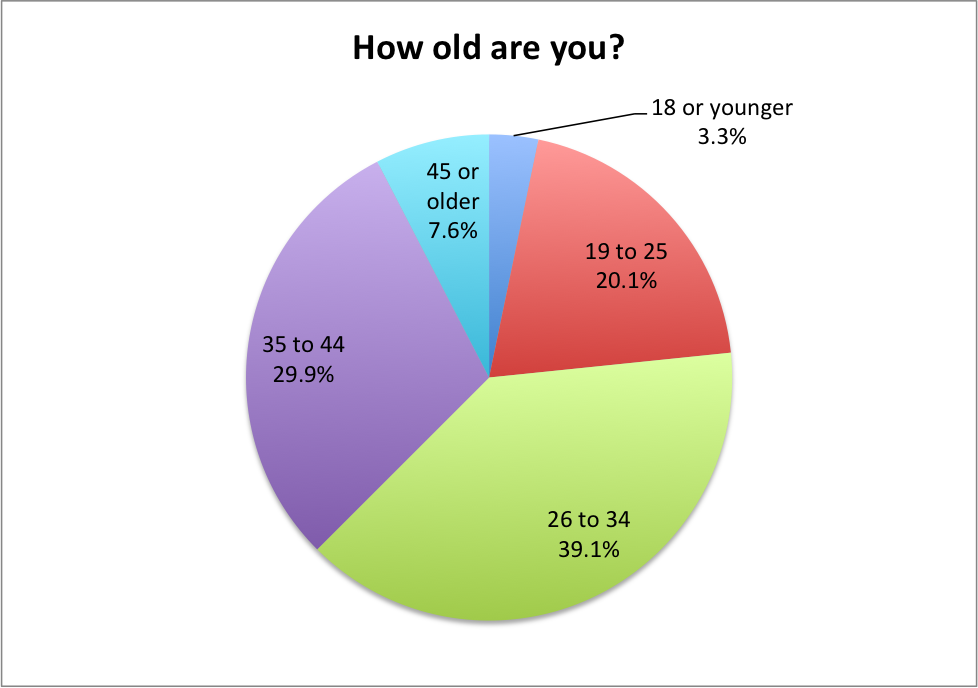

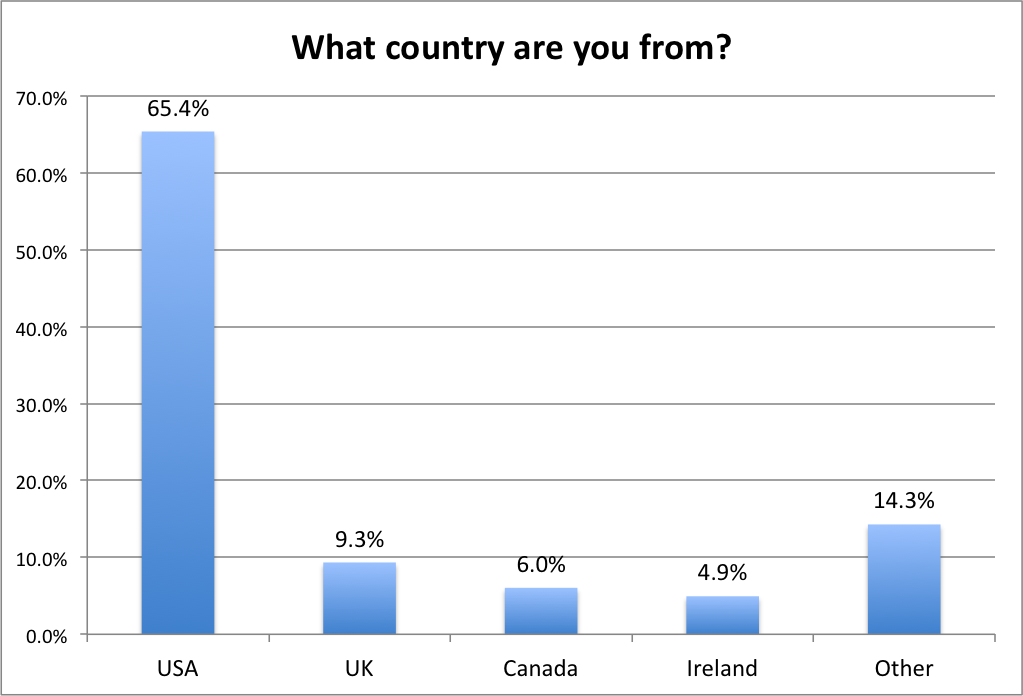

When you’re talking about what the typical respondent looked like, they were male, between 26 and 44 and from the United States. Those three segments were by far the largest, with each accounting for over 65 percent of their segments. That said, there was still solid diversity within the mix, with over a quarter of respondents being women and over 20 percent of them fitting into the tiny 19 to 25 age group. The United States and three other countries—the United Kingdom, Canada and Ireland—dominated the results for country of origin, but the survey had quality reach, with respondents from 19 countries in total.

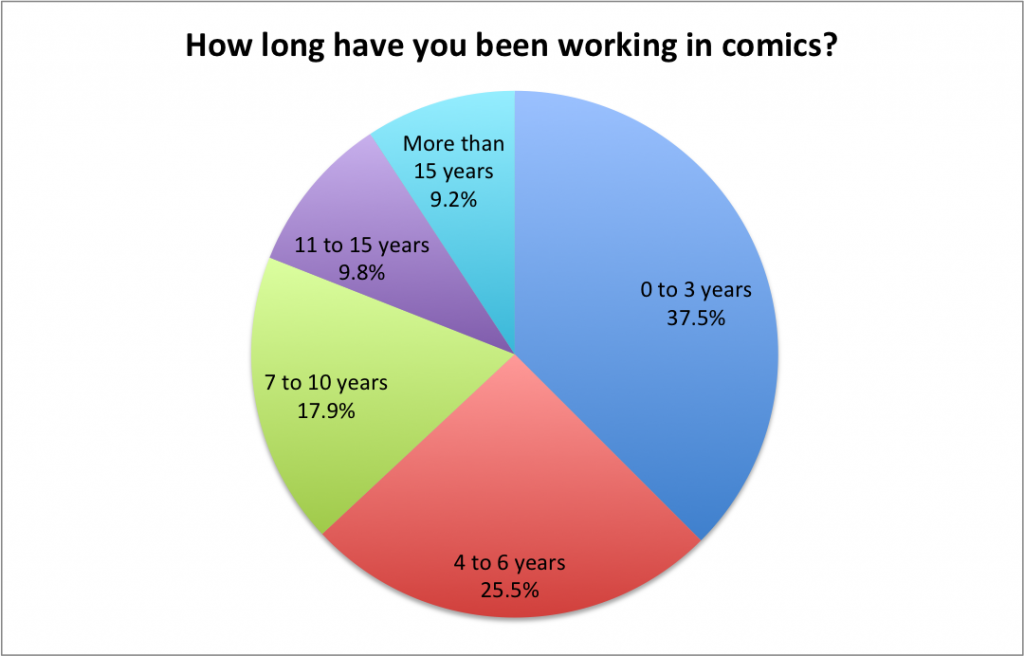

Sixty-three percent of respondents have worked in comics for 6 or less years, which matches the age groups we saw in the previous section and is fitting considering that a significant portion of survey respondents were gathered via social media.

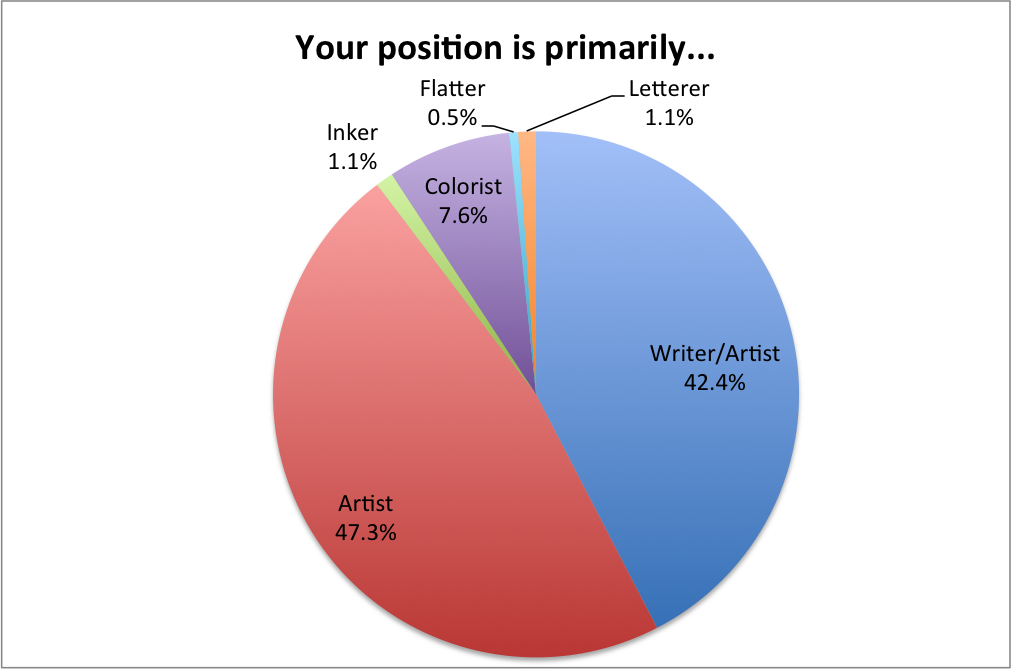

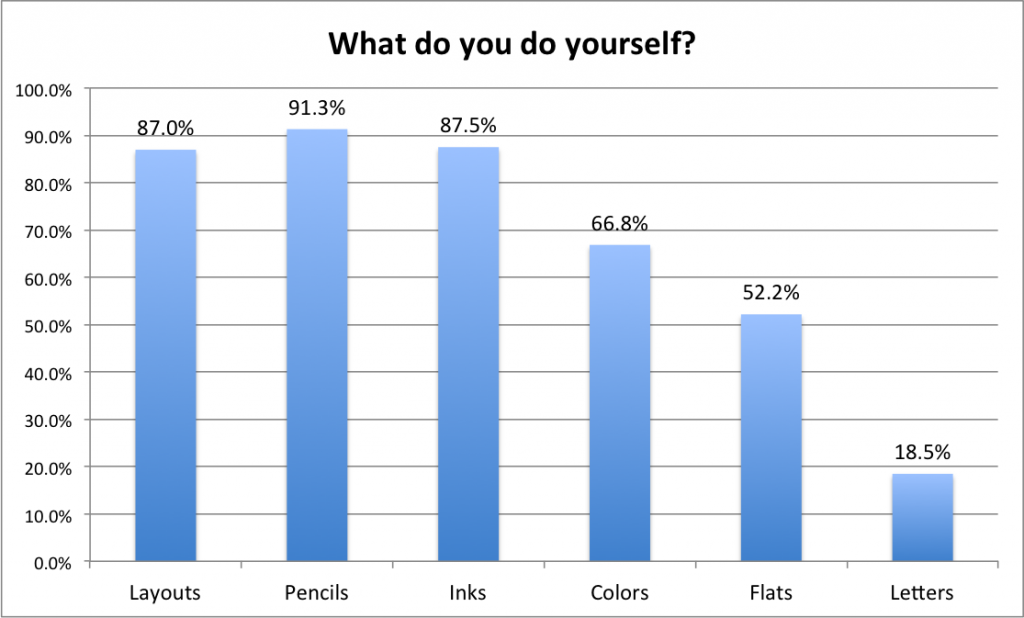

Each of these three graphs are interesting in their own right, but they work better in concert. There is a curious lack of artists who identified primarily as anything besides writer/artists, artists or colorists. By itself, that graph makes it seem like no inkers, flatters or letterers responded at all, but when you take a look at the second graph, a reason appears: many of the people who responded do almost everything themselves. Only 1.1% of respondents identified as inkers, but almost 88% of the artists ink themselves. They just don’t primarily identify as inkers.

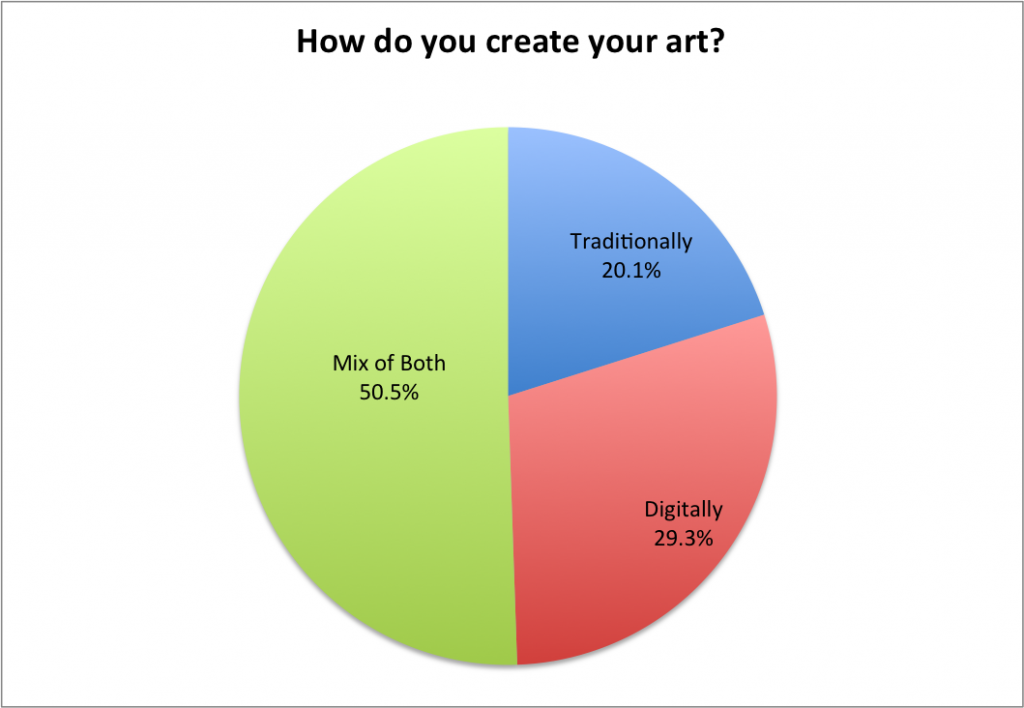

As for why that may be, a big part is what the third graph displays. Almost 80 percent of respondents at least in part create their art digitally. In the past, artists have told me life is much easier when inking and coloring digitally. The data in the last two charts shows that the anecdotal evidence may represent a larger whole.

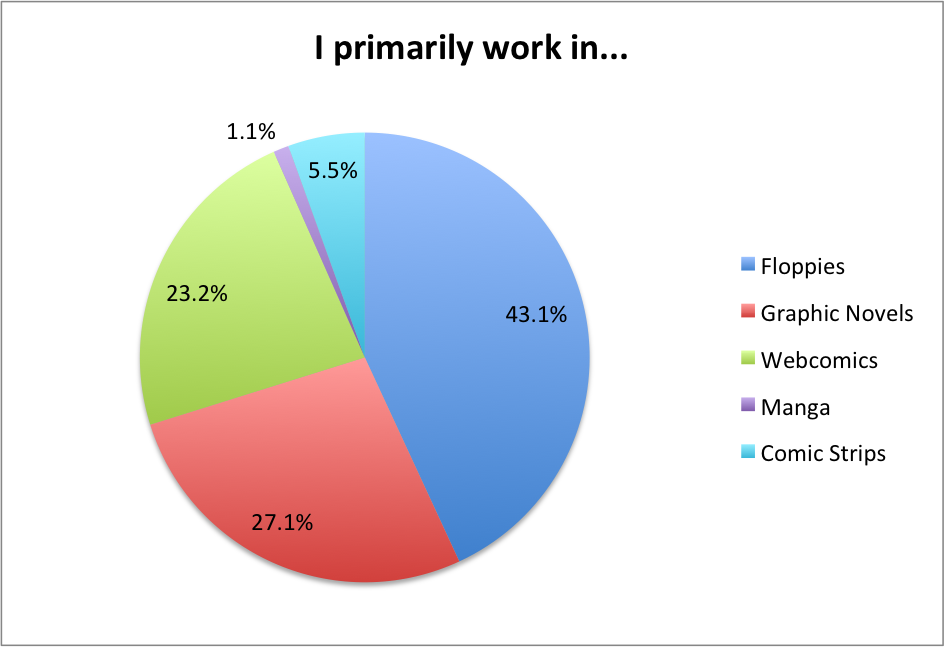

The last identifier respondents were asked for was what format they primarily work in. Over 93 percent of them work in floppies, graphic novels and webcomics, with the biggest chunk coming from the floppy market. It was excellent seeing so many webcomic respondents, but one note for going forward: the income questions were more aimed at those who work on floppies and graphic novels, which made it difficult for some webcomic creators to respond.

So what does that tell us about comic artists in 2015, at least so far? For one, you can’t put artists in a box. They’re not just men, they’re not just veterans, and they’re not just pencillers on monthly titles. A decent portion of the respondents were women who create webcomics digitally, and they do it entirely themselves. Artists, like the readership of the comics they’re drawing, are a diverse group. That’s a good thing.

Digging into the Bottom Line

Like with any field, most artists avoid discussing what they earn like the plague. I don’t blame them. I don’t sit around with my coworkers comparing salaries, and it’s a good thing we don’t: there would be a lot more fights if we did.

But it’s an important subject to broach in this case if only because of how little is known about artist rates and incomes. On a case-by-case basis, artists can make great money, but on the flipside, artists often struggle to make ends meet. Knowing where the majority of the artist population lands from an income standpoint is important in figuring out if potential issues exist, and to better inform the general populace of the state of things.

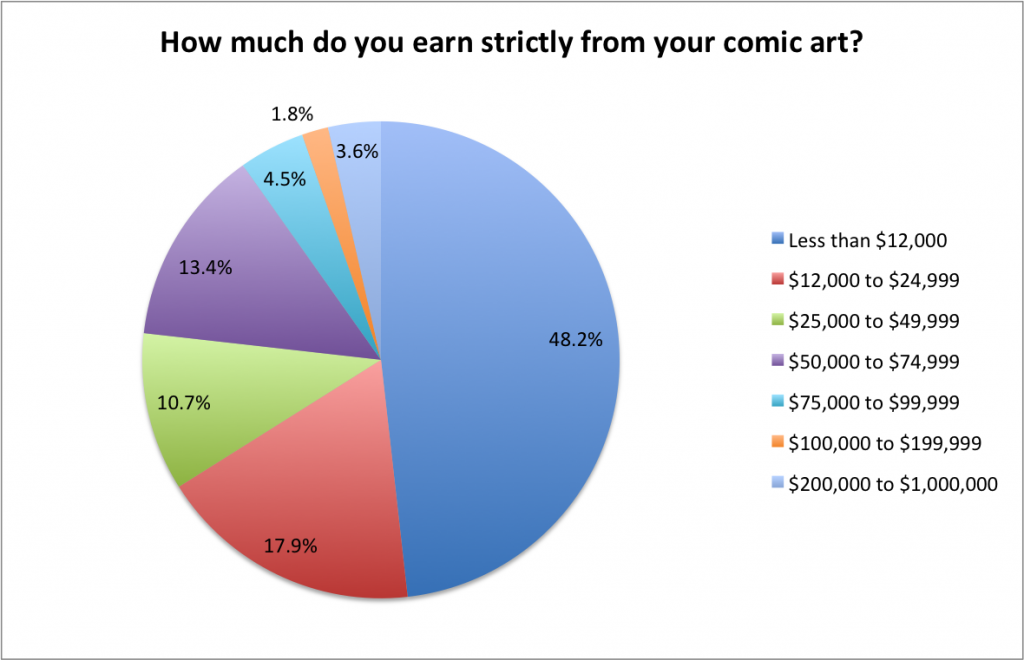

Last year, artist Sean Murphy postulated on Twitter that half of working comic creators lived at the poverty level off their work. That idea always intrigued me even if I wasn’t sure if it could be true. Now, I have a decent idea if it is. The good news is Murphy was incorrect. The bad news is he wasn’t far off. 48.2% of respondents earn less than $12,000 a year, which means they are at or below the poverty line from income related to their comic art. It doesn’t get much better from there as over 66 percent of respondents earned $25,000 or less from their art. 5.4 percent earn six figures off their art, but that’s a small part of an ugly piece of pie.

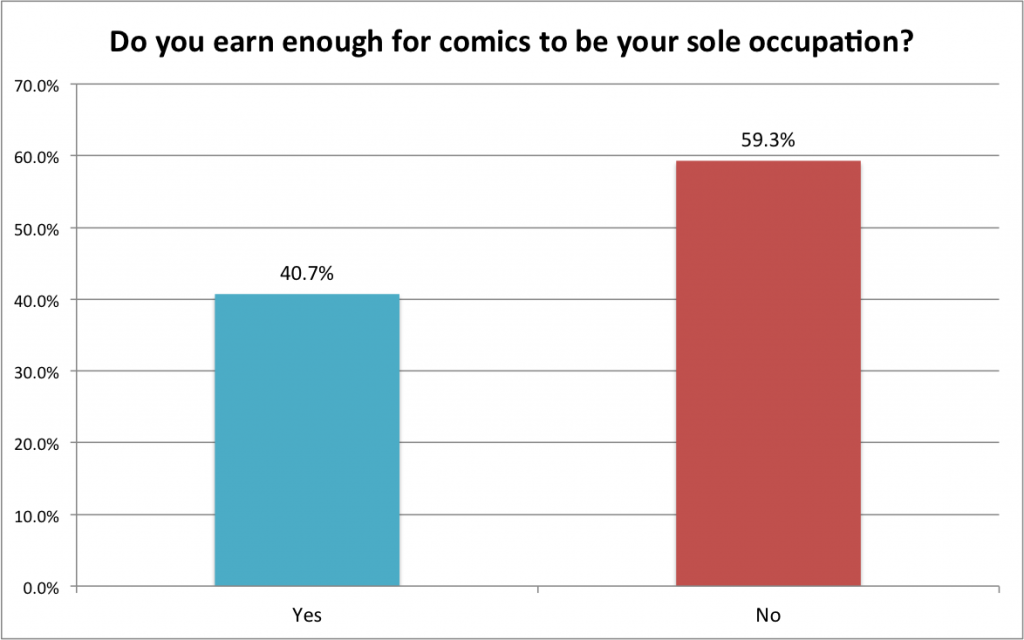

Forget getting rich though. Can artists even make enough to get by off their art? Mostly, the answer is no, they can’t. Almost 60 percent of artists who responded shared they can’t make a living off their work. What that means is many artists live interesting double lives. While many mentioned that they did freelance illustration, animation, advertising work, storyboards or other art related jobs to supplement their income, there were others who worked in factories, as bartenders, or even in one special case, lived off earnings as a figure drawing model and a tarot card reader.

Others bring in income from alternative sources, including working in a shared income household with a spouse and leveraging Patreon and other crowd-sourcing outfits to help them get by. Artists may not be making the big bucks, but they are a resilient and resourceful group.

Before moving on to the next bit of data, consider a few important factors from the previous section. As I said before, context is important, and what we saw before helps give a narrative to the low-income levels reported above. Those factors are:

1. Many of those who responded are young

2. Many of them are newer to comics

3. Many work in webcomics, and internet based work is harder to capitalize off financially

That by no means makes it less alarming that such a significant portion of working comic artists earn so little, but it does hopefully at least change the optics of the presentation. Many of the responding artists were the ones who would profile as lower-income in any field, just based off of age, experience and medium. That said, what other fields out there have low incomes that are so easily explainable, and what other careers is it considered to just be part of the deal for those who do it?

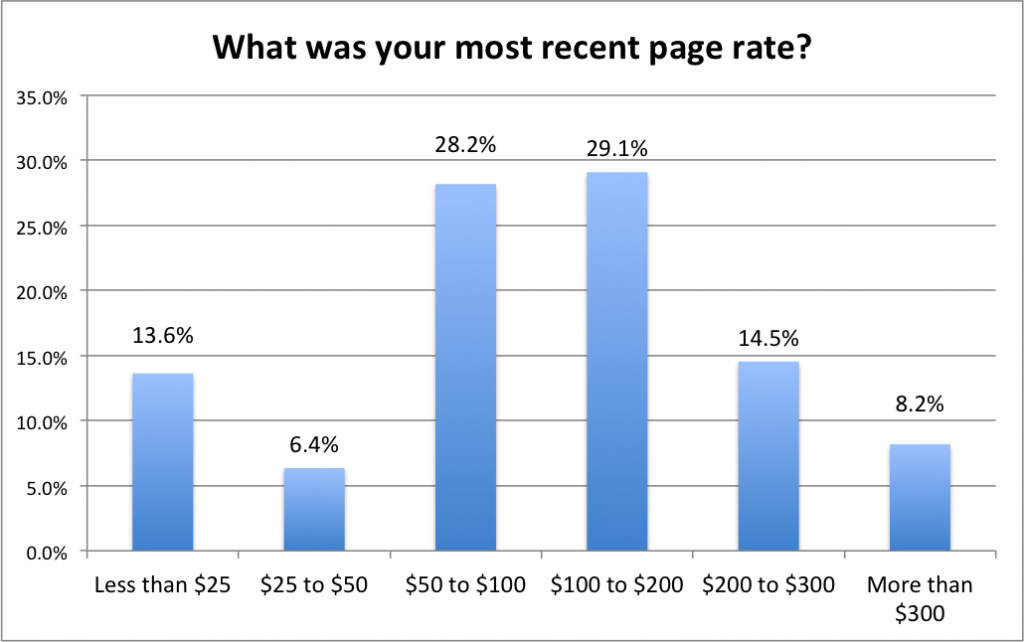

The page rate results were very interesting. If you based the overall results off page rates, you might wonder why so many artists struggle, with almost 30 percent making $100 to $200 a page—or $2,000 to $4,000 a 20-page comic, in terms of gross revenue—and over 50 percent making that or more.

But factor in that even the fastest artists are only able to draw 12 full-length comics a year, Charlie Adlard not withstanding, and it becomes more evident why artist incomes are so low. Most artists cannot draw that fast, and even if they could, they have to find gigs paying those rates all the time. Many artists fear a lull in their workload, and it’s easy to see why.

Let’s say you make $100 a page, which isn’t bad relative to your peers. But what if you’re not a fast artist and you only get hired for two three-issue arcs at $100 a page? The math reveals we’re talking about $12,000 earned in a year, and that’s before taxes and all of those pesky living expenses being taken out. That’s where things get murky, and where art becomes a job paired with financial hardship.

That’s not to say getting a page rate within such a range is a bad thing, relatively speaking—it’s on the higher end of the spectrum—but as Janelle Asselin brought up on Comics Alliance, we’re talking about 91.8% of respondents coming in below the creator recommended page rate for artists…from 1978. That’s problematic in an era of heavy inflation and additional costs that didn’t exist in the late seventies. Seeing that list of page rates makes it obvious why many struggle to make a living as artists.

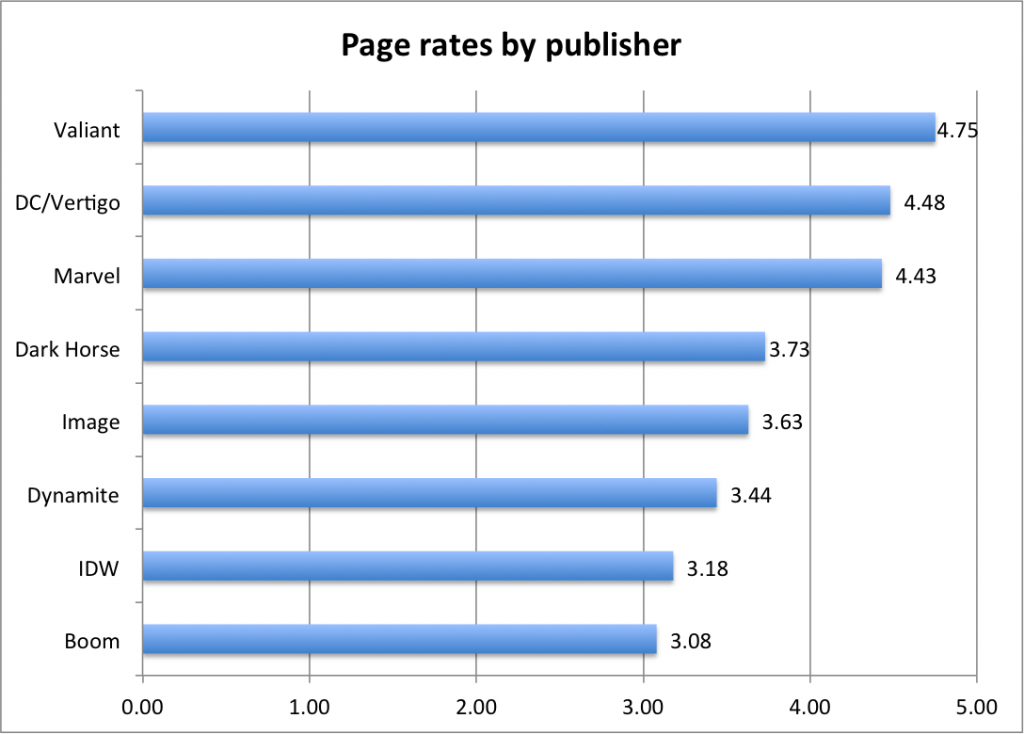

So if page rates are a struggle overall, it seems valuable to see how they break down by publisher, as each of them handles artists in different ways. Thankfully, asking artists in bulk can provide insight into who pays more and who pays less in comics, and the results were very interesting.

A few quick notes before digging into this:

1. I only included the publishers in the graph as options as they’re the eight that have the highest percentage of the floppy marketplace per Diamond. Other publishers were available to be mentioned in an “Other” category. Also, this is where the population gets slightly reduced, as this part is only applicable to floppy creators and some graphic novelists.

2. The scale works like this: 1 is less than $25 per page, 2 is $25 to $50, 3 is $50 to $100, 4 is $100 to $200, and 5 is more than $200. Anywhere in-between those numbers falls between the two spectrums.

Now, you may be surprised who came out on top. You may be, but I’m not. As someone who has spoken to Valiant creators and the Valiant team, it has become clear that (a) creators enjoy their experience at Valiant and (b) Valiant believes creators do better work when they are well compensated. Crazy idea, right? The numbers back it up as Valiant had more artists rate them as a 5 than anything else. In fact, they weren’t rated any lower than a 4. That’s impressive, and as a publisher it’s clear they value artists, especially in relation to their peers.

IDW finishes lower on the list, but save for a few outliers pulling their average down, their overall results were on the higher end for artists. Having spoken with an IDW representative as well, they shared that their lowest rate is $25 an hour for proofreaders. Artists themselves earn no less than $150 a page there, with most coming in higher than that. They also shared that artists at IDW get to retain the original pages for their art, which gives them added value on the back end through the sales of pages.

Finishing last on the list was Boom! The good news is they ran the gamut with page rates all over the spectrum. The bad news is they paid creators more than $200 a page less often and less than $25 a page more often than almost any other publisher. Regardless of what type of artist you are, $25 per page is below minimum wage when time hours are factored in, and it’s very hard to live off just that.

Oni did well in the “Others” category, typically paying pencillers between $100 and $200 a page, which is impressive for a publisher of their size. First Second, a boutique graphic novel house, paid one creator $100 a page. As far as creator-owned goes, Heavy Metal seems to have a decent deal, paying an artist who works on a book for them $75 a page while still giving them the back-end to work with.

Speaking of creator-owned, in terms of Image, their page rate isn’t a page rate, per se. According to participating artists, what Image (or writers on Image projects) doles out is an advance on money earned on the back-end, rather than money that comes on top of royalties, and it scales depending on the project. It’s a way to help the cash flow problems that come for artists on these types of gigs.

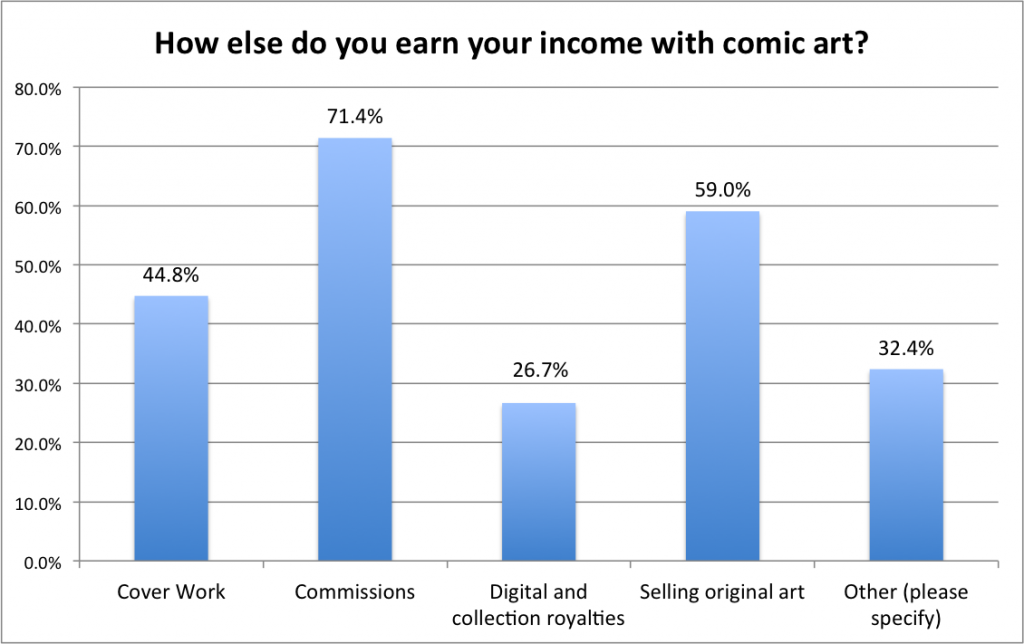

One question that intrigued me was how do artists supplement their income beyond page rates? There were four main options I had considered—cover work, commissions, royalties and original art sales—and those all are heavy parts of the mix. Commissions are something that almost every artist does as they’re easier to do and can be more time-friendly.

The “Other” section was a bonanza of artists with entrepreneurial spirit, as many do a hell of a job in getting their art out there in unique ways. Some leverage conventions and outlets like Etsy and Society 6 to get their art out there, selling buttons, zines, prints, art books, and even 3D printed figures. Others do comic style work in advertising and large-scale publishing settings, doing logo design and commercial illustration. The most audacious of artists self-publish their own comics rather than going through publishers.

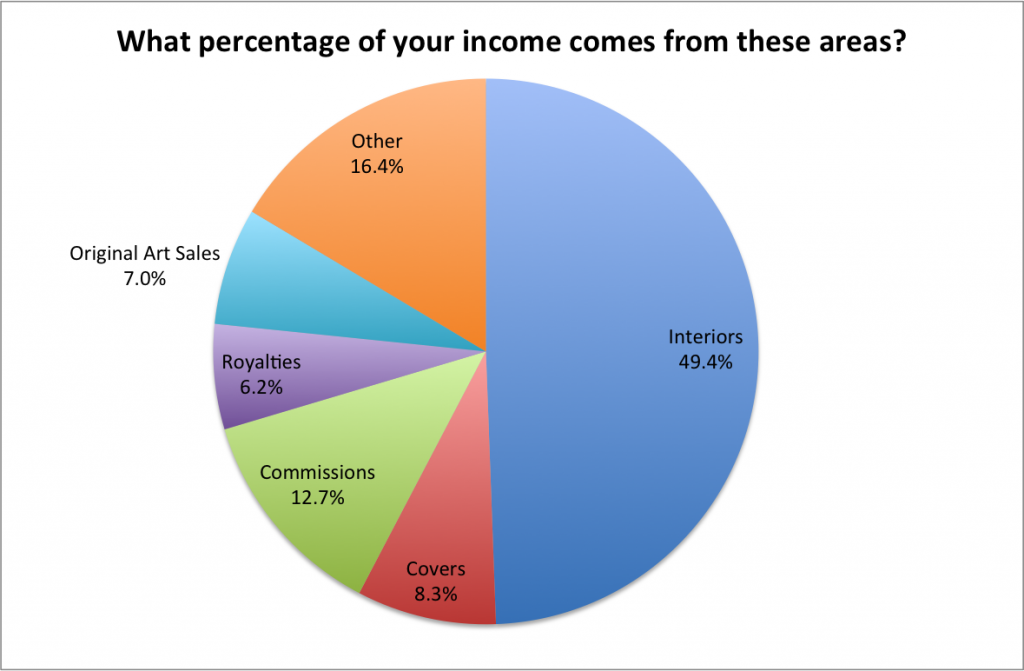

Even with all of those other ways artists can generate their income, almost half of artists’ revenue comes in from interior work. Page rates are what the industry is primarily based around, so it isn’t surprising, but it is fascinating that such a finite and potentially unreliable revenue stream is still the backbone of the way of life for artists.

One thing I wanted to note about this: as you saw in the chart earlier, royalties are not something that are often factored into artist incomes—only a little over a quarter of artists earn money from them—yet relative to its place in the mix, royalties bring in about as much as original art sales and covers for those who responded. The reason is not everyone gets them, but when they do it’s a huge chunk of the total, and it’s not just webcomic creators. Many creator-owned artists I’ve spoken to suggest that once you get deeper into a run, trade and other collection sales can generate enormous amounts of income.

The Trials and Tribulations of the Comic Art Life

While the money side of the art life is an important one many don’t consider—often including artists themselves—an element that we the readers rarely think of is the human one. When we lament the quality of art in the latest issue of (insert Marvel or DC title here), many don’t consider the amount of time and effort that went into creating each panel and page. Does it mean you have to like it? No. But what we’re about to go through is why you should respect it.

Beyond that, this section will feature questions to better arm younger or newer artists with valuable knowledge that will help them better and more safely approach the business of comic art.

Everyone thinks they are overworked. I think I’m overworked, and I work 40 hours a week at a desk at an advertising agency (not a minute more, though!). It’s hard not to feel like you’re slaving away at a job when you could be out doing better things, and that’s for the people who range from despising their jobs to enjoying them. For comic artists, where we’re talking about a job where “career” intersects with “passion”, the scale can be tipped into altogether frightening levels.

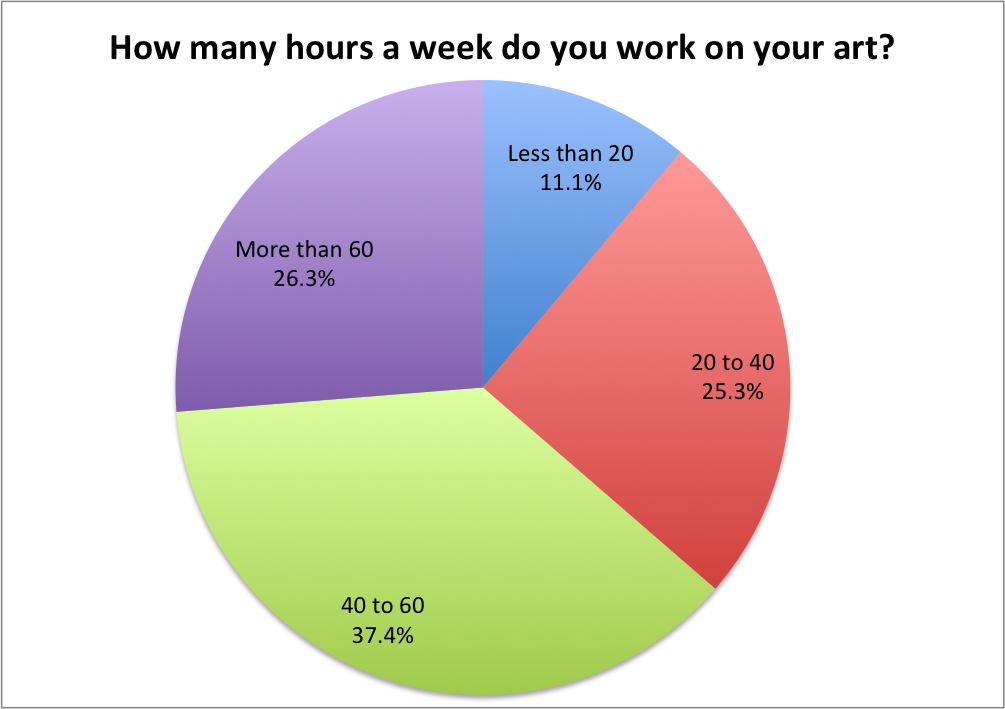

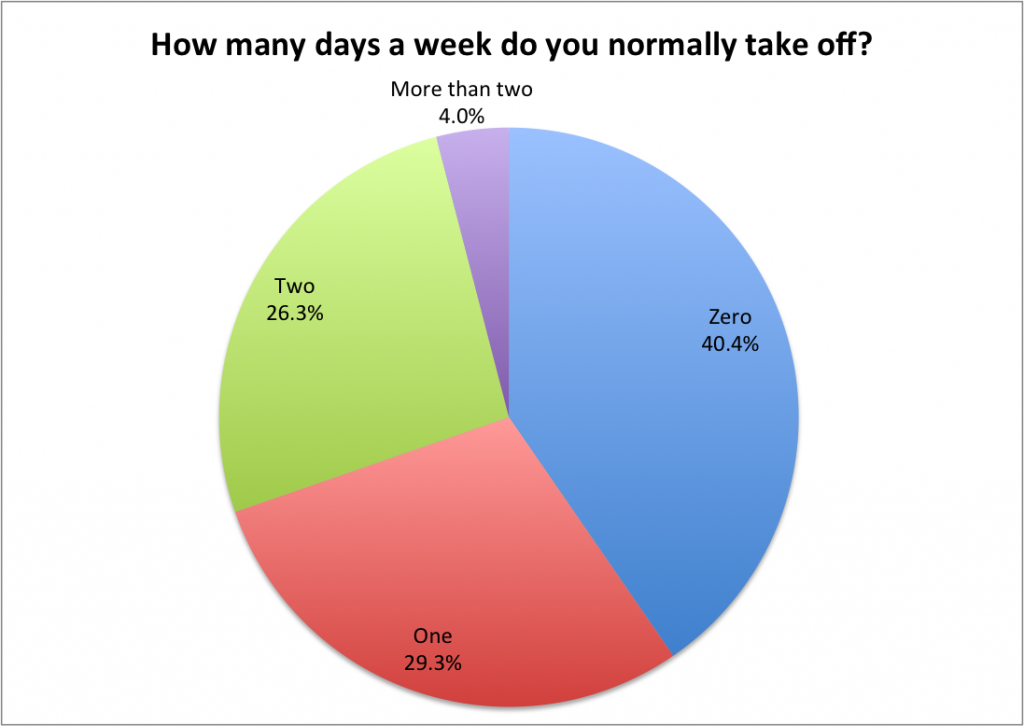

Almost 64 percent of respondents work on their art 40 hours or more a week, with 26.3% of them working over 60 hours a week. While it has been shown that most Americans (and many other nationalities) work more than 40 hours a week, these numbers show the downside of doing what you love for a living. If you want to succeed as a comic artist, you better be prepared to work for it.

And that includes working weekends, and every other day as well. Over 40 percent of respondents shared they work every day of the week on their art. Almost 70 percent are working six days a week or more. While many people out there work multiple jobs to make ends meet, one thing to consider is this: being an artist is a solitary and stationary job. When you’re working seven days and 60+ hours a week hunched over a drawing board or, at best, stuck in a room with a Cintiq at a standing desk, what kind of impact does that lifestyle have on your mind, body and soul?

Sadly, that was not a question I asked on the survey, but it doesn’t take much to guess an artist’s lifestyle can have negative ramifications, either now or later on in their lives.

Part of the reason artists work as much as they do is the pummeling, monthly nature of comics. It may seem like it takes forever between issues of “Batman”, but I bet if you ask Greg Capullo (who is more Terminator than man), it goes pretty damn fast. Trying to meet deadlines contributes to the level of work artists take on, and are a big part of why you don’t see artists making significant runs these days.

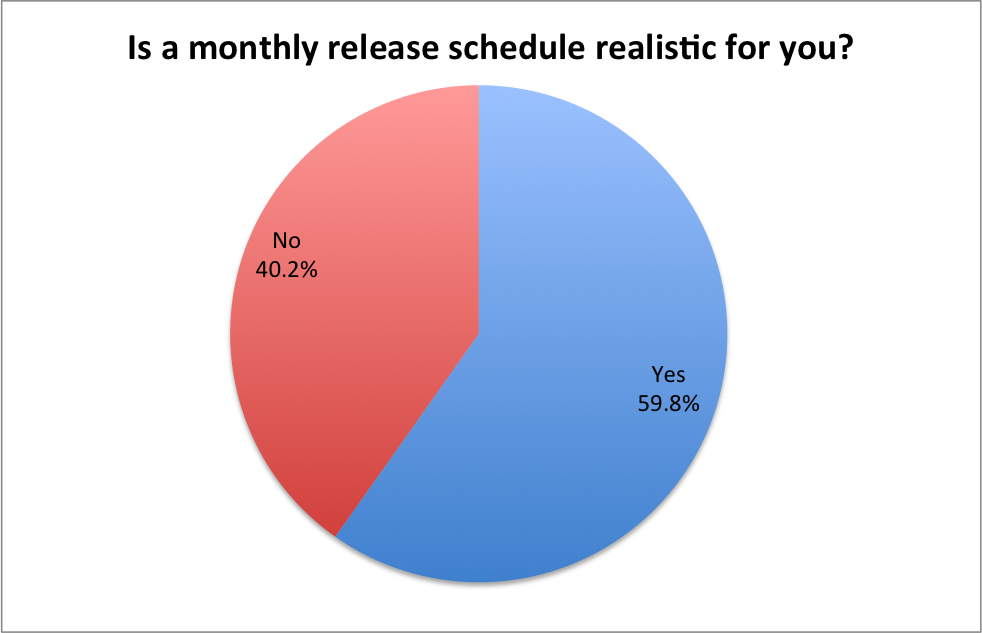

Yet, almost 60 percent of artists were fine with the monthly release schedule, although it isn’t certain if they’d be fine with that 12 issues a year.

Of those who said no, many shared what schedule would work better for them, and the most cited span was releasing a comic every six weeks. While bi-monthly came in as the second most shared answer, the third one was a bit surprising: quarterly. I don’t think we will see that any time soon, or at least not from the Diamond market, but it’s easy to see the appeal.

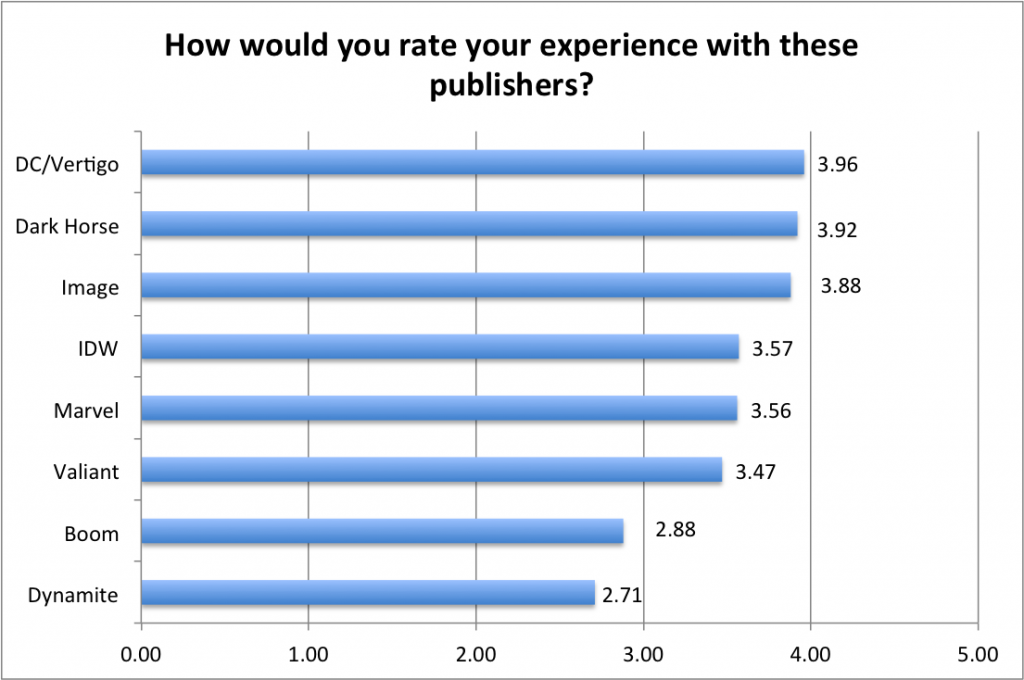

To continue the look at publishers from an artist’s perspective, respondents were asked to rate their experience with the same publishers that were featured in the page rate question. For this one, 1 means “Never work with them again,” 2 means “More bad than good,” 3 means “Middle of the Road,” 4 means “A quality experience,” and 5 means “One of the best.”

It’s interesting how tiers formed between the publishers, with the top one led by DC/Vertigo. While they’re often lamented for doing stupid things, DC/Vertigo has long been respected (at least by creators, if not the public) for the way they handle things on the back end, and things are rumored to be getting even better after the move to Burbank. Meanwhile, Dark Horse and Image have built their business models around creators, and them finishing at #2 and #3 respectively reflects that.

What is intriguing is how low Boom! and Dynamite finished, with the bad nearly outweighing the good. They both finished below their competitors, and when paired with the page rate results, you see a consensus of sorts forming about artist experiences. Again though, only a fraction of respondents worked there, so this data may be less indicative of a greater whole than in other categories.

Other publishers mentioned garnered great notes, as First Second, Heavy Metal, Archie, Oni and ComixTribe all earned applause from responding artists.

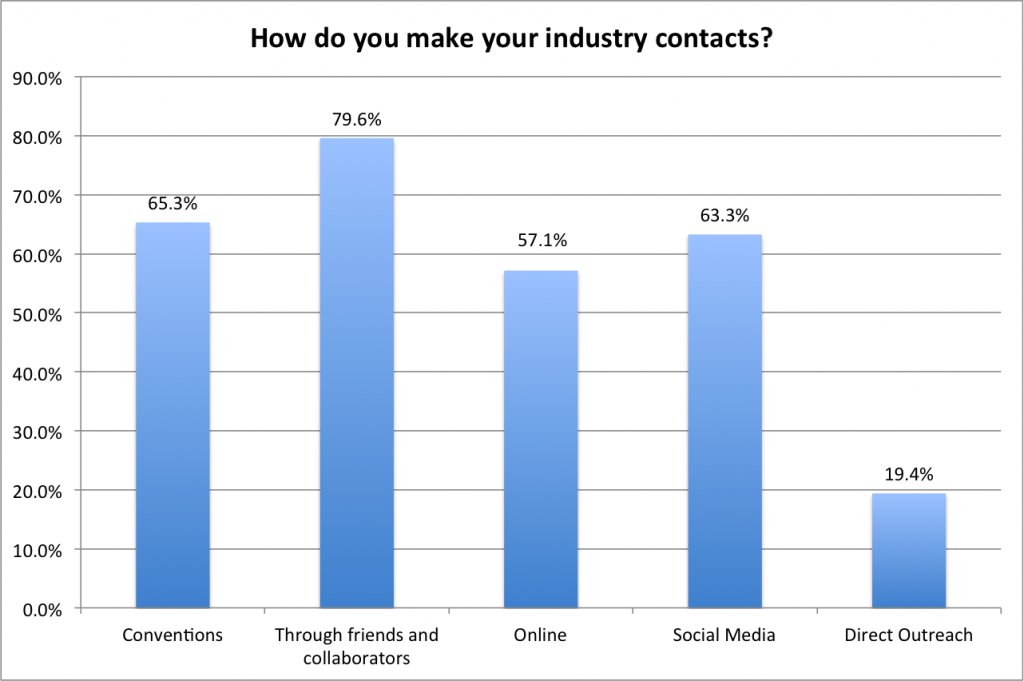

One thing of interest to me is how artists make contacts that could, in theory, hire them. Meeting people through friends and collaborators is the clear leader, with conventions taking the second spot. Social media is powerful, with over 63 percent of respondents saying they meet industry types through avenues like Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr. That is worth keeping in mind when you go about your day posting things. Big Brother is watching, and he may want to hire you.

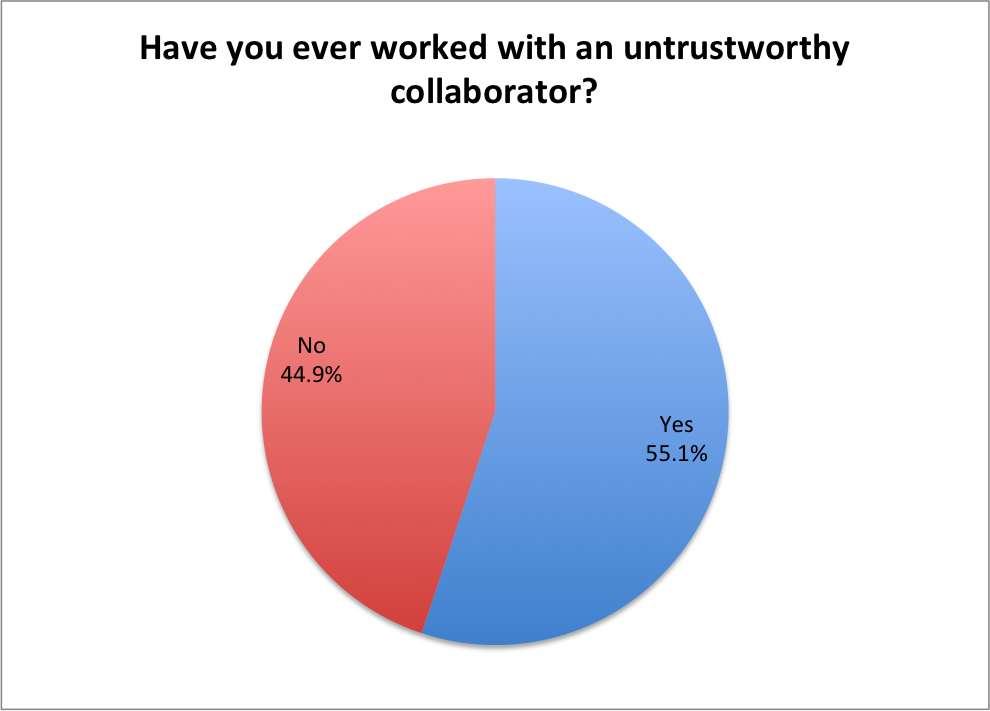

If you speak with enough creators of all varieties, you’ll hear horror stories about partnerships going awry. It comes up sometimes in conversation with creators, and it was something that seemed of potential interest to artists. Are untrustworthy collaborators something one might expect when a project is coming together?

If those who responded to this question are to be believed, it’s not a question of if an artist will work with someone of suspect nature, but when. More than half of responding artists shared that they have worked with someone they couldn’t trust in the past. This idea is alarming by itself, but the extended answers made it even more so.

Some labeled it as part of the business of making comics, but some had harrowing experiences, most often built around being bilked out of money or being cut out of rights. Others have seen more dire examples of this, like one female respondent sharing that a collaborator used their project as a way to try to sleep with her. Another said they had partners who exhibited much more interest in building their brand than treating the artist humanely. Another worked with a notable writer that spent their entire partnership alternating a lack of responsiveness with rude behavior, all the while attempting to remove the artist from royalty deals and any discussions with the publisher. Things can get dark, and they can do so fast.

The point is it’s important to be careful if you’re an artist, or any creator really. Try to find out who you’re agreeing to partner with beforehand as that can help mitigate any potential issues going forward. As one artist shared, negative experiences teach you a lot. That doesn’t mean you have to learn that the hard way.

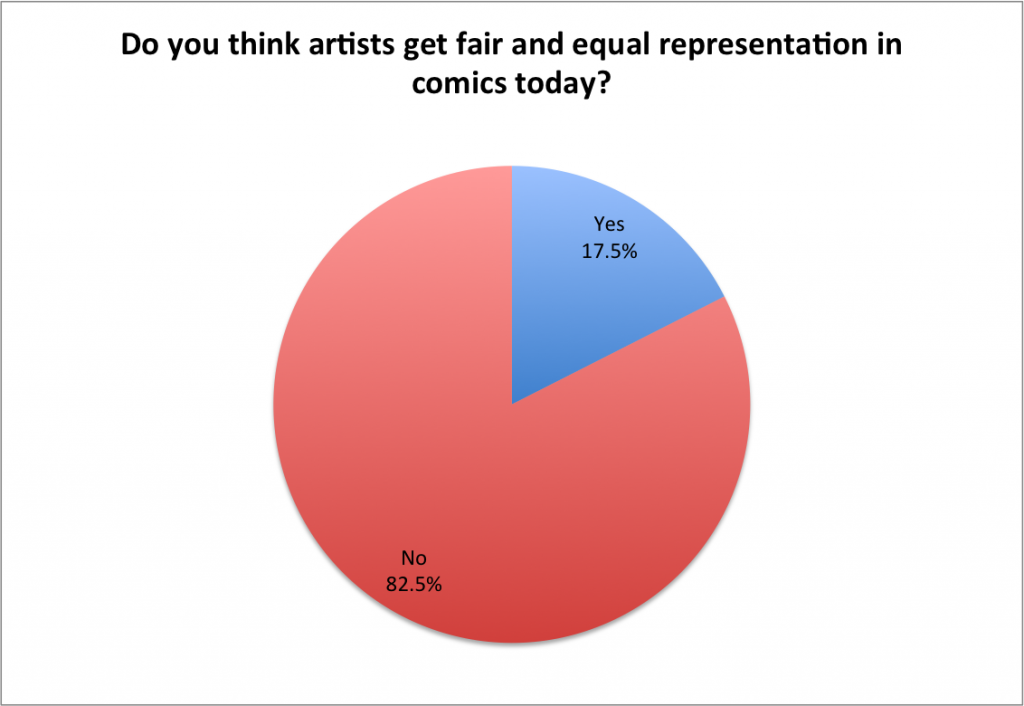

The next question of the survey was one of perception, and it’s an important one. Do artists think they get fair and equal representation in comics today? The simple answer is no. Almost 83 percent of artists answered in the negative about this. The answer is complicated though, and the reasons are diverse, with most who responded in the negative sharing a reason.

More often than not, the answer related to equality. More than a third of those who said no do not believe artists get equal attention from publishers, press, readers and everyone else. Whether in reviews or solicits or cover credits or even general comic discussion, artists view the conversation to be about writers with artists being viewed more as “just cogs in the machine,” as one artist put it. In the minds of artists, most people don’t even understand what they do. Perhaps because of all of that, many respondents don’t believe they’re appropriately compensated for what they do, which is backed up in the data we’ve shared above.

Most admit that we’re in a time of a “writer-centric” market, and know these periods are cyclical. Artists don’t blame writers—most share the belief that the average writer wants the best for artists—but it’s still a point of lamentation for them.

These same ideas were reflected when I asked artists about the greatest issues artists faced today. Most shared that the biggest problems they have are related to money. The career of an artist is the rare one that both lacks stability and the high wages that make those low times more palatable, and this impacts artists on all ends of the spectrum.

Many view the volume of artists in the market today as a major contributing factor to their financial struggles, as some think the sheer number of artists make wages go down, which most economists would agree with. A number of respondents suggested the need for standardized rates or even a guild—not a union, but a guild—that can protect artists from being preyed upon by collaborators and publishers.

Unmentioned before is the question of time. We tackled that in the survey above, but it came up often as an issue. Time is a precious commodity to artists, and the lack of it leads to many of them suffering fatigue, stress and, sometimes, depression. Again, there’s a cost to doing what you love for a living, and many artists who responded feel it.

The Hazards of Love

Value.

It’s an important word in the comic industry, and something used in a lot of ways. During the heyday of the 90’s, value drove the speculation boom and the eventual bust of the industry. It’s often a subject of debate today, as people wonder if women and minorities are valued enough, both as creators and as characters.

But that word means something different altogether to artists. Value is a multi-faceted word to them, as it doesn’t just mean one thing, it means all things. It means publishers and collaborators valuing them enough to pay them a livable wage. It means readers valuing them enough to support the comics they read. It means the press valuing them enough to give them at least equal attention as their collaborators or the fictional characters they depict, or at the bare minimum, to get their name and role right.

And the reason it’s so important is that, like with anyone, these are the things that make artists value themselves. It takes a lot of love to sit at a desk for 16 hours a day, 6 days a week, and draw, draw, draw. You have to have a deep reservoir of passion for what you do to keep going for the long haul, and even then, it’s easy to burn out or quit entirely. To keep those flames stoked (and to keep food on their table), artists need help from non-artists.

This piece isn’t about trying to affect great, widespread change. I’m not trying to incite artists to unionize and stand up to the man or anything of that sort. It’s about raising awareness as to what it’s like being an artist in comics today, so readers, publishers, writers, reviewers and everyone else knows just a little more about what they do. It’s about today’s artists aiding those of tomorrow, and helping those same people know who and what to watch out for, and what’s fair.

The comics Internet spends a lot of time talking about the groups impacted by the perception they face and the treatment they receive. That is fair, and something everyone should keep an eye out for. But artists—pencillers, inkers, colorists, flatters, letterers—comprise more than half of the working creatives in comics, yet they are often underpaid, overworked, and forgotten when it comes to touting the comics they help make special.

So what’s the life of a comic artist like? It can be a spectacular and rewarding one, but it also could be much better. A lot depends on us. It all comes back to that word. Value. How we—and by we, I mean everyone in comics, from publishers to readers—value artists going forward could help define everything from the merit of the comics we read to the quality of artists’ lives.