Cthulhu Rises – Lovecraftian Comics in the 21st Century

Issue #11 of Providence by Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows is a curious exercise. After ten issues following a straightforward historical story— in the 1910s journalist Robert Black sets out to tour New England and discovers various supernatural phenomena— this issue shifts into montage mode. It shows the passage of time from 1919 all the way to the early 21st century. Throughout the issue various characters and locations previously met in the series, all obvious analogues to the works of famed horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, are slowly intermingled with the real life people who helped to spread and popularize the Cthulhu Mythos; from Robert E. Howard to William S. Burroughs.

As fact and fiction become one we see Lovecraft ‘taking over’ the 20th century. One page near the end shows Cthulhu plushies, T-Shirts and board games; he is everywhere. Despite dying young, poor and (mostly) unknown, Lovecraft had achieved unimagined success in the afterlife, becoming one of the most famous horror writers in history, whose creations and style are copied endlessly.

This is especially true in the world of comics. From the last decade alone we had Miskatonic, Orphne, Innsmouth, Some Notes on a Nonentity, Lovecraft PI, Lovely Lovecraft, Locke and Key, Innsmouth, Herald: Lovecraft & Tesla, The Woman of Arkham Advertiser, Mythos: Lovecraft’s World, Reanimator Incorporated… and that’s just a partial list. In the last ten years alone we have seen three different adaptations of Lovecraft’s novella At the Mountains of Madness (by I.N.J Culbard, Gou Tanabe and Adam Fyda respectively). Moore and Burrows were right – these are Lovecraftian times. But what led to this sudden burst of popularity for a previously little-known author? And why so specifically in comics?

The first and most obvious reason is that Lovecraft’s stories are in the public domain. Like the similarly popular Sherlock Holmes and Dracula, the works of Lovecraft are entirely free. If you want to adapt them or to make a sequel or just to borrow some characters – no one is going to stop you. But this is also true for many other works of fantasy and horror in the public domain, yet no one rushes to make scores of graphic novels based on the works of Lord Dunsany. Pulp scholar Bobby Derie (Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos, Weird Talers) noted once that while Lovecraft was not very well known in his time he had the fortune of being known to the right people. Amongst his few fans and correspondents were people who would themselves go on to become big names in the worlds of horror fiction. Robert Bloch (of Psycho fame) actually wrote Lovecraft into one of his early works, the short story “The Shambler from the Stars.” You know that apocryphal story about how very few people attended the first Velvet Underground concert but every one of them went on to form a band? Lovecraft’s circle of colleagues was basically like this for fiction.

This same literary circle is also the one that tied Lovecraft to the world of comics. Julius Schwartz is mostly known today for his editorship at DC Comics and for his reprehensible behavior, but he began his career in the world of pulps and was even Lovecraft’s literary agent for a while. Other writers from that circle (such as Frank Belknap Long) also contributed to comics. This only makes sense – comic books could be seen as a cultural continuation of the pulps, taking over the same niche of fast-produced and fast-read commercial fiction aimed (mostly) at the young and less discerning readers.

-

From EC Comics’ “Portrait of Death” -

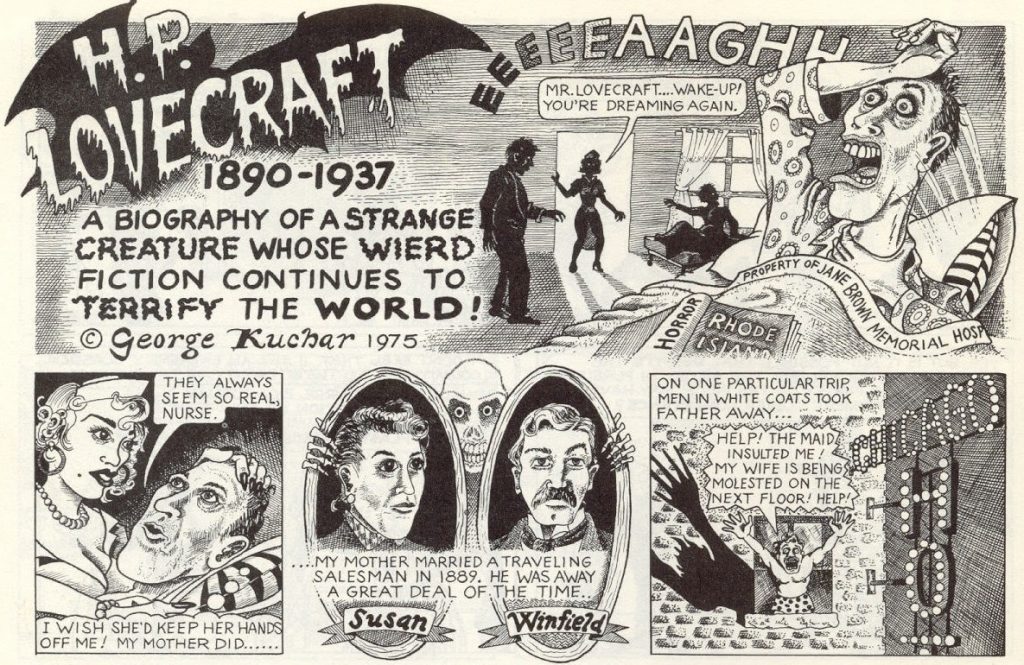

From Arcade’s biography of H.P. Lovecraft

Comics’ love affair with Lovecraft began early on. You can find examples of adaptations stretching all the way to the 1950’s: with EC adapting Lovecraft’s “Cool Air” as “Baby… It’s Cold Inside” and “Pickman’s Model” as “Portrait of Death.” Later adaptations would be published by seemingly every company possible; from the mainstream Dell through the alternative Last Gasp all the way to Marvel Comics. Most of the adaptations were either truncated or otherwise transformed, assuming those making the adaptations even bothered asking the rights holders. Fidelity was not the point – the point was that Lovecraft became part of the DNA of the comic-book industry. Issue #3 of alternative comix magazine Arcade (1975) even contained a three-page biography – showing the interest in the man goes beyond his fiction and into his life’s story. There’s now a whole sub-genre of comics with Lovecraft as the protagonist, ranging from full biography to semi-embellished horror tales to full on alternate realities.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

By John Reilly, Tom Rogers and Dexter Weeks.↩