Island, 8House, Form, Format: Brandon Graham and the Exploration of Ultimate Freedom

When it comes to making creator-owned comics, a lot of the talk from writers and artists as to their appeal is built around the idea of “creative freedom.” Working on your own comics versus crafting them at another publisher is the difference between effectively doing what you want and doing what you want within the very specific parameters someone else has set up, and even then your creative choices need to be approved. The attraction to that is obvious.

Even as children, we crave the ability to do what we want when we want. Once we get the ability to do that, the game changes. As adulthood and the shackles of things like “bills” and “responsibility” kick in, freedom becomes an illusion, often especially for artistic types. Just ask any creative who works at an advertising agency. So for many comic creators, creator-owned is a dream come true.

Most working in creator-owned aren’t really doing anything that different. It’s an avenue to tell the comic stories they envision rather than something someone else developed, but in many ways, the product feels the same. Just look at the original Image launch books, some of which were analogues of existing popular comics with gifted artists driving the ship. In comics, it can just mean creators get to define their own path when it comes to the 20-page comics they’re producing. That’s a great thing, and many of my favorite stories are realized because of the allowances this provides them.

But part of me hoped for more exploration of the form and format of the medium in these stories. Yes, comics have evolved a lot in the last 10 to 15 years, especially online. However, print has effectively stayed the same, delivering stories of similar lengths on predictable schedules before arriving in affordable collected editions and maybe slightly larger hardcovers later on. It’s the formula, and everyone’s comfortable with it.

But sometimes comfort is overrated.

Every once in a while I’d hear people like cartoonist Jake Wyatt suggest ideas like a Shonen Jump style monthly magazine for kids, and my brain explodes like that guy in Scanners. Why isn’t that a thing? In this growth time for comics when a diverse readership is buying comics of more varieties than ever, why aren’t we seeing more creatives and publishers take bold leaps like the one Wyatt suggested? It’s confounding. It’s also, again, comfortable.

Thankfully Brandon Graham’s never really seemed that interested in making people comfortable.

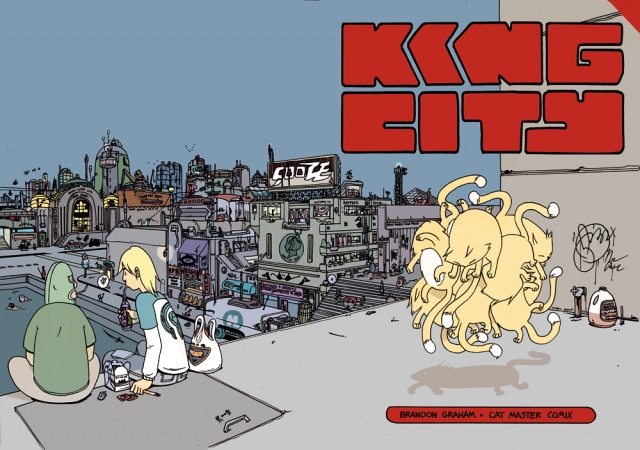

Graham’s a guy I first started reading with his series King City, a book initially released at Tokyopop before wrapping up at Image. That was a great book, and one that definitely underlined his lack of interest in doing comics the same way everyone else does it. While originally manga-sized at Tokypop, at Image, the book was Golden Age sized. That means it was a little more than 3/4 of an inch wider than current comics. As infuriating as it was to need to buy bags and boards of that size for one comic, it was worth it. The size played perfectly to the way Graham delivered the story and details within. He’s a guy that would spend two pages displaying a city with no “story” attached or the minute details of what’s in a vending machine because it felt right, and the choice to publish the book at the size he did helped those elements breathe. It was a good thing for readers. It also made the comic feel more special and stand out amongst its brethren in the shop.

His later work on Prophet pushed the way ongoing comics were told in a direction that could only be slotted under the “atypical” column. While we’ve gotten used to rotating creative teams on comics from many publishers, Graham’s efforts at curating that book redefined the intent of that method. While Graham was the name on the masthead of the revitalization of the Rob Liefeld created property, it was a series that found creators like Simon Roy, Giannis Milonogiannis and Farel Dalrymple alternating lead and supporting roles on the book. It recalled a phrase writer John Arcudi said recently on my Off Panel podcast: “egoless comics.” That run on Prophet – which continues in Prophet: Earth War – was less interested in being “Brandon Graham’s Prophet” than it was a “really damn good Prophet comic made by a bunch of talented creators.” And it was better for it.

Those efforts that shied away from the accepted methods of comics were tremendous. However, they were only prelude to what Graham had in store for us with Island and 8House. While both couldn’t be more different from another, they each highlight the restlessness Graham approaches the medium with. Could 8House just be Graham telling a sprawling story that defies genre conventions and typical comic narrative structures on his own? Sure. But it wouldn’t be as good, and it assuredly wouldn’t be as interesting.

So far there have been four issues of 8House, unless you include the in-universe but not line labeled From Under Mountains by Marian Churchland, Sloane Leong and Claire Gibson. It opened with a two-issue arc called Arclight by Graham and Churchland. The third issue was subtitled Kiem and was written by Graham with art by Xurxo G. Penalta. The fourth was the first part of a two-issue arc called Yorris by Fil Barlow and Helen Maier. Each story explores a different house/world of the shared universe Graham has been developing, but it isn’t governed by him in any real way. Take this quote from Barlow at the back of Yorris Part One for an example of how this world works.

“Brandon’s brief was simple, ‘You can do anything you want.'”

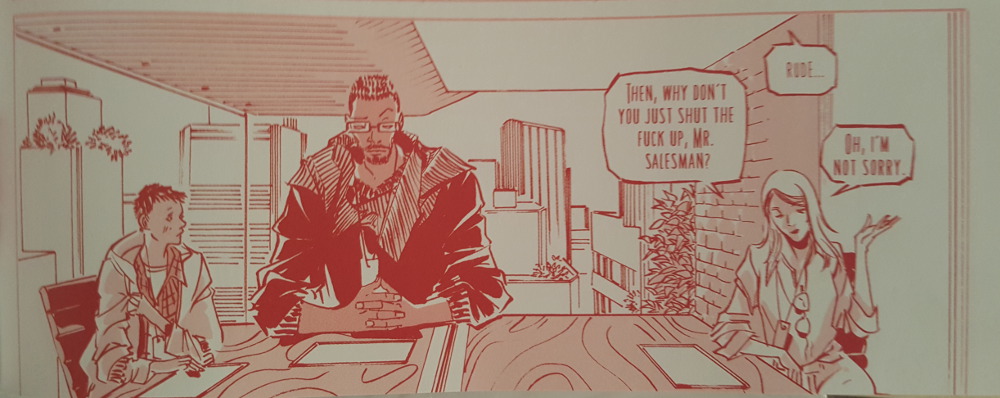

In simple terms, Graham is Airbnb’ing his own comic, but in a way that empowers creatives he admires to tell stories within an architecture he developed. As if he’s saying, “come over to my house and play while I’m not there.” He’s less about creating a road for other creators to drive on. Instead, he gives them the tools they need to build their own road. And it’s working marvelously so far.

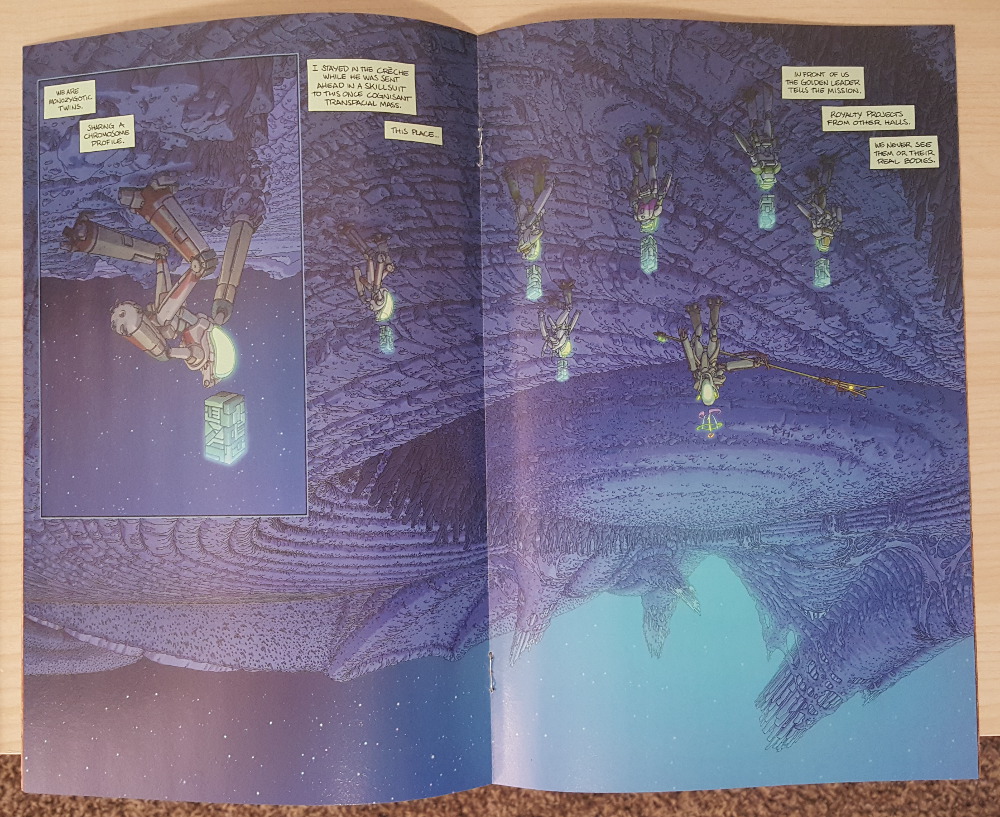

Each arc is special in its own way, and it’s been fun seeing how each new creative team approaches their part of the world. Arclight’s an introduction to one house and its cast, delivering a haunting fantasy story that is beautifully illustrated by Churchland. Some might find it a spare read, but I found its more spartan approach to be alluring, often letting the art speak instead of the writing. Yorris feels equal parts sci-fi and fantasy, and it’s an impressively imaginative comic that recalls nothing I’ve read or seen before (in a good way). And Kiem, which was my favorite so far, is a gorgeously drawn science fiction tale in an otherworldly land filled with unexpected and unexplainable things. There’s a section of the story where the words are delivered in the usual orientation but the art is delivered upside down that was particularly notable. It plays with perspective in fascinating ways, and helps cement the jarring experience the lead character – the titular Kiem – is going through at that moment. Penalta’s a mad genius, and it’s thrilling to see an artist like that get the opportunity to realize their work in such a way, especially when pairing with a like-minded partner in Graham.

I’ll readily admit 8House isn’t a book for everyone. Each arc feels disconnected completely, with Arclight, Kiem and Yorris reading as if they were worlds apart (which makes sense, as they are). The narratives are delivered in ways that don’t let readers off the hook, challenging them to either get it or get out. Kiem just straight up ends seemingly mid-story, giving those who adored the ending of The Sopranos something to rejoice.

But it’s because of those things that this book feels so special. In an era of homogenous entertainment, 8House is a book that has zero interest in pleasing everyone, which makes it feel much more exciting. It rotates creative teams and worlds and characters and stories with the greatest of ease, giving us snapshots into the universe of the comic from different perspectives in a way that nourishes us as readers but doesn’t nurse us along. You can’t just be a passive reader with this book, and it rewards those who give it attention. Better yet, it’s clearly bringing out the best in the creatives involved. That is especially the case in Yorris, which is shown throughout the issue, not just in their story.

Yorris the comic is a fascinating and evocative read that delivers grand ideas in an original package, and that would have been enough on its own. But the backmatter made it all the more exciting, especially as Barlow and Maier – two creatives with a long history in animation – walked readers through how their careers evolved. It showcases the opportunity 8House has provided.

“When conceptualizing Yorris, Fil & Helen wondered about their time in animation, ‘Imagine if we had the chance to do our career over again, but in comics. Knowing what we know no, with all of our experience, what would it be like? What if our designs belonged to us, if we owned all of those characters, and they all existed in one concept that we have complete control over. What would that…project be like?’

This was how Yorris was conceived, as an alternative reality career, or a career re-imagined.”

The strangest thing about the backmatter is it gives the story an even greater sense of sadness to it – it was a surprisingly emotional read – while also bolstering the sense of hope behind the project as a whole. Barlow and Maier have seen struggle despite successful careers in animation, and Graham’s creative freedom has given them the platform to realize something they’ve long desired in their careers: a fresh start. While Yorris can be read in many different ways, there’s part of me that wonders whether or not Graham is the transformative representative of light in the story. Was Yorris the opportunity that has helped them find the light within their own work?

Island does similar things for creators with a much different format. It’s a thick, 100+ page anthology series that comes out roughly every month. It features a laundry list of creators and all-around interesting folks contributing one-shot and multi-part comics as well as essays to its pages. It’s curated by Graham and the wondrously talented Emma Rios, and as Rios told me a while back, it finds them taking “a moment in our careers in which we basically can do whatever we want and be published” and accomplishing something special with it.

Rios called magazines “a safe zone to try weirder stuff in (the) company of other people,” and Island is certainly that. Through three issues, it has featured comics by Graham, Rios, Dalrymple, Roy, Dilraj Mann, Tessa Black and many more, and each is as different from one another as different can get. That’s the beauty of the almost trade-length format. It allows a lot of space for creatives to stretch their legs, and we’ve seen these storytellers do so in spectacular fashion.

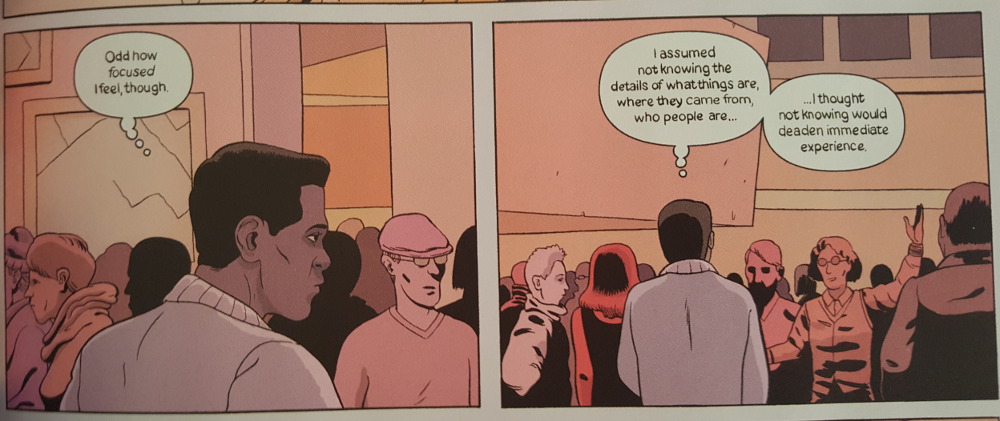

While there’s plenty to choose from, to date, my favorite story has been Ancestor by Malachi Ward and Matt Sheehan. While it’s only a quarter of the way done – its first part appeared in Island #3 with the second part arriving in Island #5 – it’s the type of very human science fiction I love. It explores our obsession with technology, except it takes it several degrees and years past where we are. It’s an illuminating and oddly creepy story, and one that inspires self-reflection. It’s also the type of comic you don’t really see that often due to dreadful questions like “what’s the market for it?” and “will it sell?” As readers of SKTCHD can attest to, those questions are ones I’m attuned to very closely, but sometimes you just want comics that explore the medium and tell stories in exciting ways without having to think of what the average comic shop customer may or may not do with it.

Rios herself delivers a gorgeous, heartbreaking sci-fi story about identity in “I.D.” Told over the first two issues of Island, Rios showcases her abilities beyond the artistic. As a cartoonist, Rios revels in the details and thrives with the freedom the opportunity provides her, delivering a thoughtful, unforgettable tale in the process. It’s a well-researched read that feels real, both technologically and emotionally. Rios doesn’t pull any punches in her delivery, and because of that, the story sticks with you in a way few others do.

Those are just two of the many stories that have been delivered in the first three issues, and the rest help further showcase the diversity of artistic voices the comic game has today. Many of whom would otherwise go unseen, save for the opportunities something like this provides. The magazine format alongside Rios and Graham’s taste as curators gives the book a perpetually unexpected feel, as you never know what you’re going to get when you pick up an issue. Take the essays for example. I’m confident in saying Island is the only comic I’ve ever read that features pieces from both a neurologist and a lawyer who is a contract negotiation expert, and I doubt I’m the only one with that experience.

Never knowing what to expect is a good thing for me, but like with 8House, this is a project that isn’t necessarily for everyone. I’m an unabashed fan of Island and even my mileage varies greatly from story to story. I read every story and essay and appreciate them all for what they do, but there are certainly favorites. That’s to be expected given the goals of the magazine, but some may not appreciate the fluctuation of perceived quality both within each issue and from issue-to-issue.

And that’s fine. Graham’s efforts are not built on the ideals of most comics. Both 8House and Island are projects that dispense with convention because they have no interest in being like everyone else. Graham seems to be the type of creator who is more interested in failing big rather than accomplishing small, incremental wins, and both comics are all the better for that.

That’s not to say what he’s doing is treading on untouched ground. 2000 AD and Heavy Metal both belonged to the same school as Island, while even Graham’s own work on Prophet was a precursor in a way to what he’s doing in 8House. But to me, it’s hard to see any time we have a creator who is looking to challenge how comics are approached as anything but a good thing. Books like the ones from Graham or Andrew MacLean’s Head Lopper – a superb series that is being published as extra-sized quarterlies instead of a standard monthly – don’t just fit into the box they’re given. They break that box and create something new that fits them better. And who doesn’t want a little more of that?

Neither 8House nor Island are amongst my very favorite comics, either overall or on a weekly basis. Both are, however, some of the most inspiring works on the market today and, in my book, desperately needed additions to an industry that struggles with featuring diverse voices. Graham’s work in curating and developing 8House and Island doesn’t just showcase quality craftsmanship and unique storytellers seen in very few other places in comics. They deliver the kind of originality and innovation comics need more of, especially as the readership pushes further in new directions.

For some, they may seem like foreign and uncomfortable additions to the mix. But isn’t that how the future is always treated before it becomes part of the way things are?