The Story Behind the Perfect Modern Superhero, 25 Years Later

What if I told you the perfect superhero for 2020 – one who perfectly fits our extremely online lives – was actually created in 1994? A character who, because of the way he was raised and his powers, has little sense of consequences to his actions, but was a thrill to read because of it? Someone who, when his solo series launched 25 years ago, 1 became a beloved character to some because of his, well, impulsive nature?

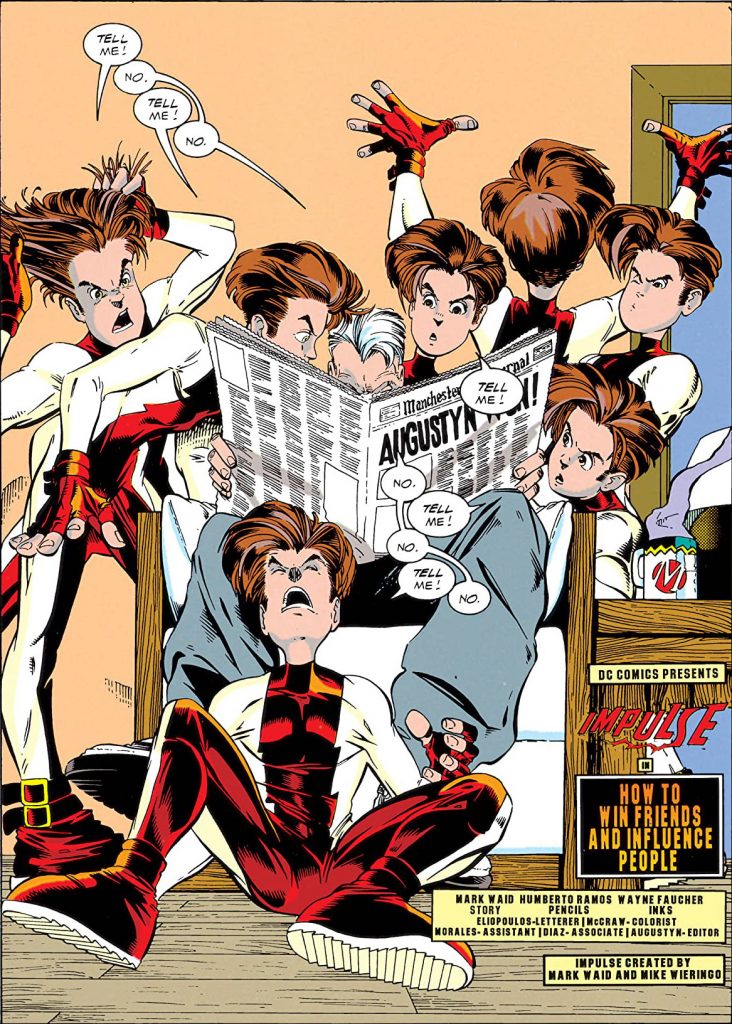

That character is Bart Allen, or Impulse as you might know him. Allen was a character rooted in the family tree of The Flash, with his grandfather being a time displaced Barry Allen 2 and other relatives being a variety of speedsters from his native time period of the 30th century. He was tethered to the history of others, but still very much his own hero in the best ways. Over his existence, Impulse has been known by a lot of different names – Kid Flash, The Flash, perhaps most inexplicably Bar Torr – and starred in many titles. But for those who love the character most, Bart was likely defined by the nearly 25 issue run writer Mark Waid, line artist Humberto Ramos, and editor Brian Augustyn 3 tackled together on the character’s solo title between 1995 and 1997.

I know that’s the case for me, at least.

I was 10 years old when the character debuted in The Flash #91, 4 but it really took Waid and Ramos’ collaborating on an Impulse for me to fall in love. There was something about that run, a rare joyousness, a palpable vitality, an energetic buzz that few superhero titles ever match. Here was a character that was like me in his youth – while Bart was chronologically two years old, he was 12 years old in appearance and mentally thanks to being raised in virtual reality – while also being aspirational thanks to his effortless coolness. Impulse was unlike anything I had ever read until that point. During that run, a lifelong adoration was formed. That’s for a simple reason.

While other comics I’ve read that are better, Impulse has the rare distinction of being the series that generated my most potent love for the medium. It formed the peak of my fandom for comics, with Waid and Ramos’ work becoming a turning point for what I hoped to get out my comics experience. 5

And that original run perseveres. In fact, having reread it for the purposes of this article, Impulse has still got it, with the energy, life and sheer fun Waid and Ramos brought to the book feeling as fresh today as it did when I was a kid. It was very much an original of a form that has become well-liked: the superhero sitcom.

That period with Waid writing, Ramos drawing and Augustyn editing has aged incredibly well, with Bart Allen being a child of the Internet before we even really knew what the Internet was. 6 So how did the perfect modern superhero come to be 25 long years ago? How did Waid, Ramos and Augustyn turn what could have been a rush job into a lasting memory for certain fans? As with many things in comics, it took a combination of opportunity, collaboration, and maybe even a little bit of fatefulness along the way.

Like most things involving The Flash in the 1990s, the story of Impulse begins with Mark Waid and Brian Augustyn. The pair arrived at DC Comics at the same time, both being hired as Associate Editors. A fun fact, but something that meant little more than the pair was forced to share an office. During that time, a bond was formed – something that went beyond professional camaraderie – and for a good reason.

“We became friends right away because we’re both hideous fanboys and we loved a lot of the same things,” Augustyn told me.

This duo orbited around each other for some time, 7 but they really started cooking when Waid began writing The Flash – starring the G.F.O.A.T. 8 Wally West – with Augustyn editing the title. And yet, the roots of Impulse began in another title they worked on together.

“It was before I was even working on Flash. I was working on Justice League Quarterly for Brian,” Waid said of the beginnings of the idea. “We were talking about doing a return of Barry Allen story there, where the fake out was it was actually Barry Allen’s grandson come back from the future.”

“We didn’t do anything with it, which is good because then when I started working on Flash, we realized we could do the return of Barry Allen in a much more dramatic way 9 and give no more thought to the grandson,” Waid added.

But that idea of the grandson coming from the future lingered, and it did so for two reasons. First, the duo had previously decided that Waid’s run was going to “be about heritage,” Augustyn noted, forming a larger Flash family through both biological and contextual means. This meant Wally West was surrounded by not just his girlfriend Linda Park, but other speedsters like Jay Garrick, Max Mercury, and Johnny and Jesse Quick. This gave them the “tapestry” they needed to tell a larger story.

The other reason was their desire to avoid bringing back Kid Flash as a character. Wally West – The Flash – had previously been Kid Flash. Everyone both expected and wanted a new iteration of the character. Waid and Augustyn were trying to avoid falling into that trap just as they had by not really bringing Barry Allen back to life. That’s why they spun a discussion about bringing a new Kid Flash to life into something that fit the idea of the character while also staying true to their vision.

“We said, ‘Okay, let’s bring the character back in spirit or in essence, but let’s give him a whole different reason for being a whole different way of being,’” Augustyn shared. “’And we’ll give him a different name.’”

Interestingly, the foundation of both Wally and Bart came from Waid himself, as Augustyn shared. Literally, as Waid’s personality was found in both of them. The editor described Waid as someone “who microwave popcorn takes too long” for, and Wally inherited that from the writer working on the book. They wanted to push that even further with Bart.

“We said, ‘Well, what if this guy is even worse and drives Wally crazy in the same way that Wally drives everyone else crazy?’” Augustyn told me.

For a quick breakdown on Bart Allen’s story, when he was born, he had a hyper-metabolism that made him age far faster than he should. When he was one, he looked two. When he was two, he looked 12. He was taken in by EarthGov, the 30th century’s government, and raised in virtual reality to help his mind keep up with his body. But this was killing him, as he’d basically be 100 physically within a few years of being born. His grandmother Iris West Allen – Wally’s aunt and Barry’s wife – brought him back in time to have Wally mentor him. 10 It did not go well for aforementioned reasons. But that virtual reality upbringing led to a fascinating character who looked at the world without the idea of consequences in his brain. He effectively lived life like he was in a video game, as if perhaps he had another life waiting for him if he died. It led to his rather impulsive nature, which Waid and Augustyn agreed would make for a good name for a speedster.

At the time they were doing this, DC had seen significant gains by killing Superman, 11 as The Death of Superman was a monster hit. DC saw that success and double, triple, quadrupled down, breaking Batman’s back, having Hal Jordan become a pretty evil dude, and having Green Arrow lose an arm in rapid succession. Waid and Augustyn knew a dark request would be coming with their book. They leveraged that idea to their advantage.

“We knew at that point that (issue) 100 was coming up, and I think we knew at that point that we were going to be asked to kill Wally off by upper management because that was all the rage those days,” Waid said. “And we’d already figured, ‘Of course, we’re not, and we’re going to do some sort of fake out.’

“But I think that’s about the time we realized that once you started loading the fish tank with Impulse as well as Jay and Jesse Quick and so forth, that we could use this new sidekick character as a real swerve, fake out, red herring. Is he going to be the new Flash?”

All of this was misdirection. They never intended Bart to be The Flash or Kid Flash or any type of Flash. He was Impulse, and that’s what he was designed to be. His own character, and that was that. In fact, they didn’t have much of an idea of what to do with him at all past his initial role in the “Terminal Velocity” story this all took place in.

“There was never a larger plan for him,” Waid said. “Brian knows that I am very much fly by the seat of my pants, and we just kind of threw it in there figuring we’d know what to do with it later.”

Later came fairly quickly, as it turned out that new youthful iterations of existing characters were also hot. The Death of Superman led to the rise of a new Superboy, and DC sensed a similar opportunity with Impulse. By the time the character debuted, Impulse was already en route to getting his own solo title.

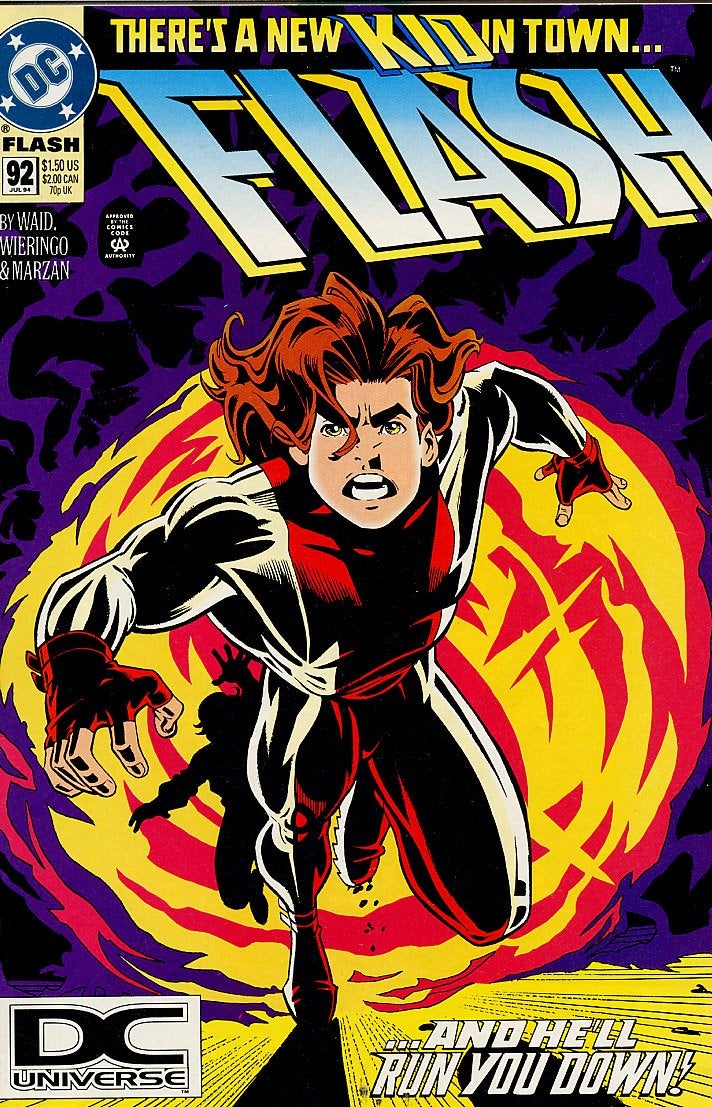

Part of this derived from the success Waid had on The Flash. When he took the title over, it was selling “maybe 50,000” copies an issue, per Augustyn. By issue #99, it was up around six figures. DC desired a spin-off, and so when then-DC Publisher Paul Levitz saw the proofs for issue #92 and the debut of Bart Allen, he said, “Let’s do that.” And that was before the issue even shipped.

The urgency to launch was reflected in the compressed timeline the team worked with. While Augustyn knew that this was a great opportunity for both he and Waid, the whirlwind nature of it was a challenge.

“The minute I said yes (to the project), they said, ‘Well, can you have it for us in six months?’” Augustyn said. “Now from jump, most books don’t come together that quickly. In fact, three months ahead of shipping is when they do their solicitation. Most folks don’t know anything in three months. It’s hard even if you know the character. Because we then had to sit down and figure out ‘how can we make this different?’”

Waid’s reason for taking on this project was the same thing that differentiated it from the pack. As much as he liked the character, Waid saw Impulse as “a chance to do a sitcom in comic book style, which I had not had a chance to do.”

“I love writing humorous characters. I love writing comedy, and there’s places for it here and there in the books that I’m writing for the superhero. There’s always been place for it in superhero books,” Waid said. “But to be able to basically just sit down and go, ‘Okay, this is an adventure comedy,’ that was what made it appealing.”

The pair even wanted to structure the book like a sitcom, with each issue being paced with three short acts: the establishment of the premise, then everything breaks, and then everything resolves. This set the book apart from the rest of what DC and really everyone was producing at the time. It helped turn Impulse into a delightful read unlike anything else on the stands. Even with that in mind, DC was not enthusiastic about the comedic nature of the book. Augustyn shared that he “got a lot of resistance for making it intentionally humorous.”

“We went into it fully expecting it to be canceled by issue 10 because it was so unlike anything else DC was doing,” Waid said.

“But it turns out counterprogramming works.”

The visuals of the book were a huge driver for the success of Impulse. While much of that was thanks to Ramos’ work on it, its foundation begins with another artist altogether: Mike Wieringo. The late, great Wieringo was the one who originally designed the character and his immediately iconic costume, setting the character on a path of not just starring in an atypical book but doing so with killer new look. Its roots were in another costume from The Flash’s history.

“We told Mike to model it off of the Kid Flash costume to some degree,” Waid said. “Brian and I both agree that the most perfect superhero costume in all existence was Kid Flash, right up there with Silver Age Green Lantern and Spider-Man. Those are like the big three.”

“And from there, he went his own way,” Waid added. “(Wieringo) played with a mask. He played with (no) mask, but we definitely liked the Kid Flash costume for speedsters obviously, because your hair is falling out at the top and that helps give the illusion of speed.” 12

While Carlos Pacheco was actually the artist on Impulse’s debut, Wieringo initially defined the look of the character. Augustyn compared Impulse’s visual development to Spider-Man’s, with Wieringo being Steve Ditko and Ramos as John Romita.

“Two different styles in a lot of ways, but both of them (were) responsible for the ultimate look of Spider-Man,” Augustyn said. “In this case, both artists contributed and while Humberto was not a creator, he was a realizer.”

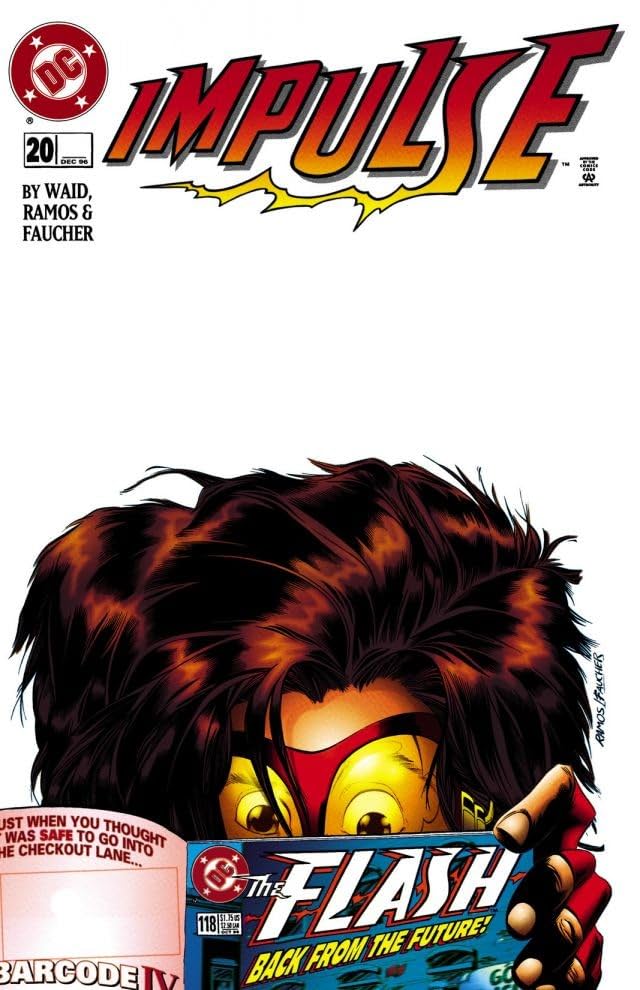

We now know Ramos as a superstar artist, but at the time, he was effectively a complete unknown. He had done some work for Milestone Comics and a Steel Annual, but in an industry defined by the look of Image Comics at the time, an artist from Mexico with an atypical style could have been an odd fit. Not for Impulse, though.

Augustyn was in pursuit of someone who fit the vibe they were going for when the “late, lamented” Neal Pozner – then Group Editor, Creative Services at DC 13 – showed him Ramos’ Steel Annual, telling Augustyn, “I think this is your guy.”

“What Neal zeroed in on was Humberto is very close to the spirit of what (we were) up to,” Augustyn said. “And he was right. Beyond our wildest actually.”

Augustyn described Ramos as “so fresh the world wasn’t quite ready for it,” with the artist’s energy on the page being palpable to the point the editor believes no one can touch him even to this day in that regard. Waid echoed that thought.

“There was just so much energy in Humberto’s work,” Waid said. “There was just so much explosive, kinetic energy, the way everything moved, the way everything was just rapid fire. That’s what I think worked for that book, (and) that there’s a youthful innocence to the characters that Humberto tends to draw. And likewise, it just translated well for the character.”

Ramos’ was often spoken of as having manga influences at the time, 14 but in actuality, the biggest inspirations for the artist on the book were two Western artists of some renown who were influenced by manga themselves.

“My two main references (on Impulse) were Art Adams and Joe Madureira,” Ramos told me. “And they still are actually, but at that time, I guess my work came from that mixture between these artists and the things that I could do with my own skills.”

Despite the impact Ramos’ art had on the book, not everyone connected with it. Like with the comedic tone, higher ups at DC “hated Humberto’s art,” Augustyn told me. He described one as being “terrified” at how Ramos’ work could cost the book its potential. That changed quickly when the numbers started coming in.

“Then the first issue ordered very well,” Augustyn said. “I think for the first 10 issues, we were actually adding readers as we went.”

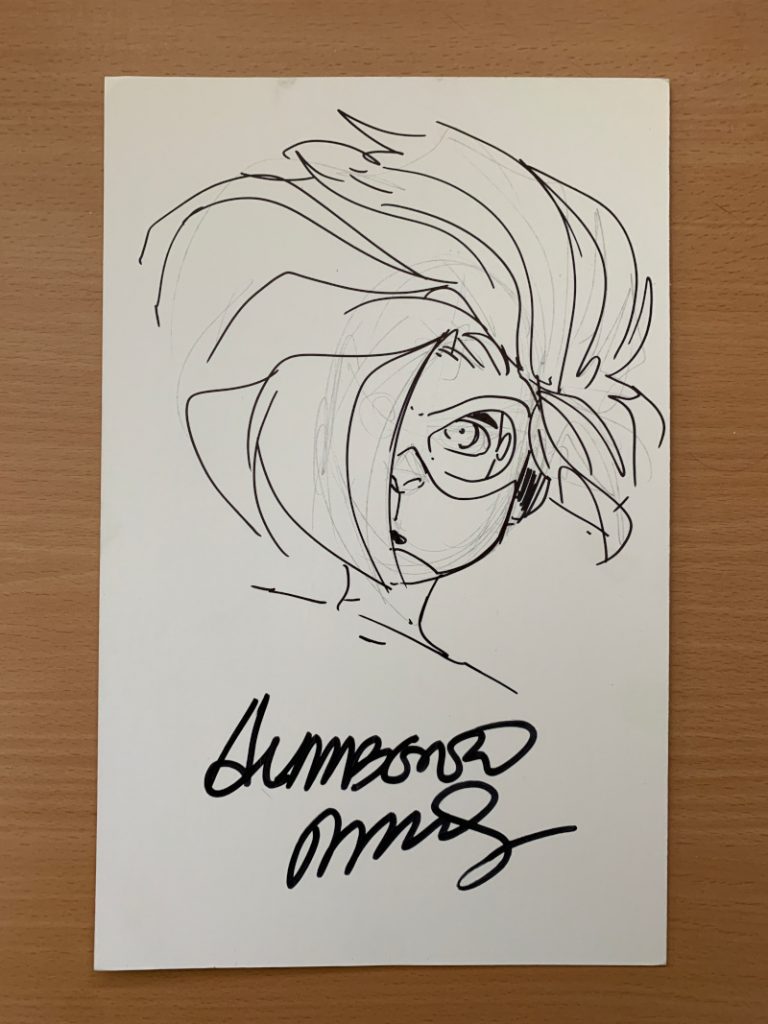

As much as I love what Waid and Augustyn contributed to this book – and I do, as they were brilliant collaborators who did something truly unique with Impulse – the person that made the title stand out as much as it did to me was Ramos. I had never seen anything like his work before, with a vibrancy and energy that radiated off the pages as I turned them. 15 There was a palpable joy in his art, and it was hard not to look at what Ramos did in this book and just smile. 16 Outlandish choices that might have driven others at DC insane with rage like Bart Allen’s massive hair and gigantic feet instead became iconic elements, permanently connected to the character in a way that was likely unexpected.

Speaking of those ideas, one of them was taken from the original design – Ramos said he was just putting his own spin on Wieringo’s design with Bart’s massive hair, delivering similar volume but taken to the next level – while the other came from nature. When Ramos thought of Bart Allen, he thought of hares and their gigantic feet that are perfectly suited for running at speed.

“That was the idea for me, to give him big feet, because it was clear that it was a kid with this hyperactive attitude and character,” Ramos said. “So I always picture him that way.”

Those iconic looks wouldn’t have happened without Ramos’ unique thought process to the character, and Waid noted that they quickly bought in on those ideas.

At the peak of my fandom for this book, I actually met Ramos at Orlando MegaCon, my first ever comic convention. It was 1997, and I timidly went up to the artist, likely babbling some nonsense about how Ramos draws so well and how much I love his work and yada yada yada. Despite the nonsense that likely came pouring out of my mouth, Ramos did a sketch of Bart for me, with his hair in its full glory. I still have that sketch, and I still often wear my hair at lengths and volumes that are ill-advised for a man with a head the shape of mine. I can’t say for sure that this is Ramos’ fault, but I cannot say it isn’t either.

The art was an obviously essential element to Impulse working as well as it did as a series, but it was more than that. As I went through my back issues of the title, one thing that struck me was how jubilant the response was in the letters columns. Fans were outrageously positive about it, in a way that extended even beyond the self-selecting positivity these pages usually deliver. Waid believes it helped that they were spinning off “Terminal Velocity,” an enormous, well-received Flash event that took place right before Impulse launched. But it was more than that.

“I still believe this, that readers are going to respond to things that are unique and that are very personal, which you could clearly tell in the way that Humberto and I approached that book, that we loved it, that we had a very distinct point of view,” Waid said. “And we had a voice. The character had a voice. We had a creative voice that wasn’t being heard anywhere else. And I think that that is appealing.”

That distinct point-of-view was of course by design. Waid mentioned a word earlier that was crucial to the success of this book: counterprogramming. Because of the sitcom-like nature of the title, they were able to craft something different enough from the rest of DC’s titles at the time that it acted as the only game in town for a certain type of story. This was a hook, and a good one at that.

And yet, it all hinged on Bart Allen himself. If the character didn’t work, the series wouldn’t. The good news is that version of the character very well may be on the Mount Rushmore of likable comic characters. Waid described him as almost like Sean Penn’s famous Spicoli character from Fast Times at Ridgemont High, minus his stoner-nature. Bart was “innocent and gliding through life,” which made him “easy to be around.”

“That’s the secret to writing Bart that people seem to pay no attention to,” Waid said. “The secret to writing Bart is that he has no guile. He has no enemies other than yeah, bad guys. But I mean…he doesn’t dislike people. You have to write him to some degree like he’s a four-year-old boy.”

“He wasn’t just guileless,” Augustyn said. “Impulse was also clueless. He had no idea that he was misunderstanding virtually everything, that he would tell you exactly was on his head without ever considering whether they wanted to know. 17 The thing about the character that made him interesting is entirely the thing that may have put off some people and certainly made him infuriating to other characters.

“But that dynamic is where the fun was.”

My favorite manifestation of this was in the third issue, an issue where Bart goes to school and somehow throughout the course of the day manages to effectively make every guy in his school want to fight him – culminating in a scene at the end where the entire school gets into a fight on the football field as Bart aimlessly wanders through – while also making all of the prettiest girls fall in love with him, without even really knowing that either thing is happening. He later becomes the most popular kid in school for similar reasons, but that ties into what Augustyn is saying. He’s oblivious, but in a way that comes off as very, very cool. 18

Of course, if it was all Bart Allen drifting through the world, it wouldn’t have worked nearly as well as it did. One flavor – even a good one – can get tired. That’s why Bart’s mentor/father figure was an absolutely essential part of the book.

“Max Mercury made it different,” Waid said. “If not for Max Mercury, I don’t know what we would’ve done for an Impulse series because he needed that odd couple foil to him. He needed the super zen, calm guy to be his mentor.”

Max Mercury was known as the Zen Master of Speed, a character that debuted in 1940 but was resurrected in The Flash by Waid himself. He was someone who understood the Speed Force 19 at the highest levels, making him almost an academic but also a full believer in these ideas. Because of that nature, he has a relaxed approach to super speed, not always running at full tilt like others. Pairing him with Bart was a natural fit, and Waid believed it came from “having long hysterical conversations” with Augustyn about what would happen if you combined the two. It was perfect: the one speedster who chooses to walk mentoring the one who never slows down.

The rest of the supporting cast was similarly effective, as Waid crafted peers and villains that matched Bart well. He “was just really looking for characters that I enjoyed writing that I knew the audience would like,” but his job was made simple because “Bart is so easy to be around that you can really put him in a story with anybody.” That manifested itself well in characters like Carol and Preston, people who helped contextualize the world for Bart while offering their own flavor.

Quick note: another prescient character in that run was White Lightning, an attractive young woman who used the Internet to gather gangs of young men to help her commit robberies. She would be perfect for this era, as she’d be goddess of social media, a modern-day Robin Hood on a motorcycle. As it was, she was a “great foil” for Bart, because her draw was her sexuality and “it just didn’t work on Bart,” Waid said. 20

“None of her attractiveness, all of it was lost on Bart.”

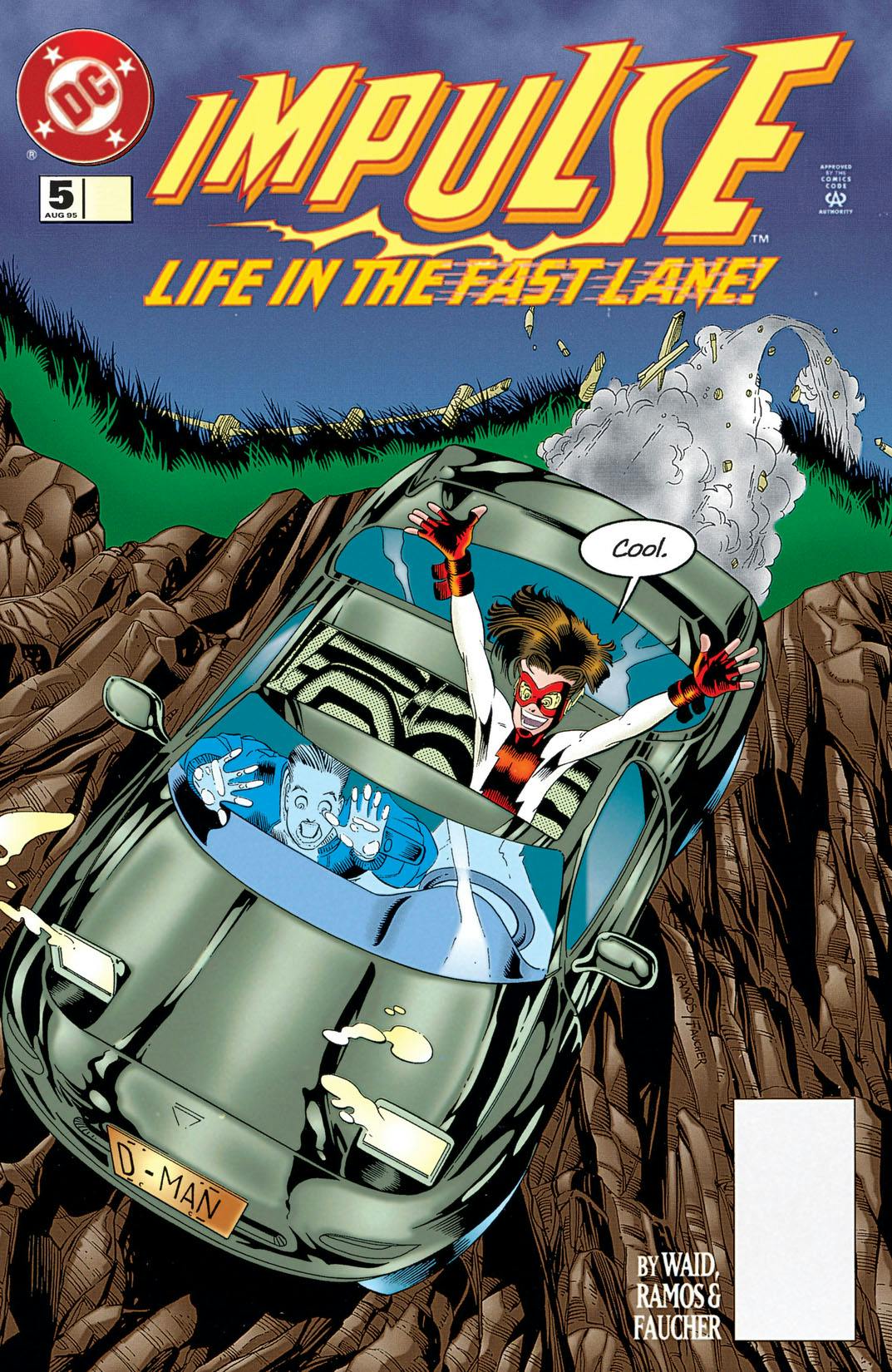

Impulse’s adventures always had a sense of the unexpected to them, as Bart’s impulsive nature led to conventions being forgotten and solutions being atypical. This was a lot of fun, differentiating the book with its perpetually zigging and zagging. It stemmed from the spontaneous nature Waid approaches storytelling with. He said he had no plan going into the book, and used issues #4 and #5 as an example. At the end of issue #4, Bart drives a car off of a cliff with little plan for what came next. He wasn’t the only one.

“I wrote that without the slightest idea of how Bart was going to get out of it,” Waid said. “Not a clue.”

The writer enjoys putting himself in a quandary and having to figure his way out of it. It’s his preferred way of writing. He realized that while working on Impulse. He learned a fair bit during this run, with one of his favorite out-of-the-blue innovations he had on the book being the “Rebus-like thought balloons,” where iconography was used in the place of words in Bart’s thought balloons. Figuring out solutions like that was a big part of why he took such joy from Impulse.

It was also a very personal project for him. As noted earlier, there was a lot of Bart in Waid, with the writer describing himself as “legendarily impatient” at that point in his life. He even set the story in his hometown, as Bart’s home of Manchester, Alabama was a fictionalized version of where Waid grew up: Prattville, Alabama.

“I set it in Prattville, Alabama and used my house and my school and then sent Humberto photographic reference,” Waid said. “So that also made it very personal, just keeping it grounded in the area that I grew up in. As much as anything, that made it a personal book.”

The core of the book and the character of Bart Allen himself came from the partnership between Waid and Augustyn, though, and that – combined with Ramos’ art – was why it was as special as it was. The pair talked about everything. How to break a story, where they were going next, who would appear. It all came pouring out of their chats.

“I never sat down in a vacuum and wrote an Impulse story or a Flash story without talking it over with Brian first because he would always make it better,” Waid said.

His long-time editor regularly advocated for longer-term thinking, pushing Waid to “think a little bit further down the road than page 22.” But that wasn’t all he advocated for. In an environment that didn’t believe in the title, Augustyn routinely fought for its existence and its identity.

“The marketing department hated the book. For the first six or eight months, the marketing department didn’t know what to make of the book,” Waid said. “And I remember distinctly the guy who was the head of marketing at that point came down the hall to Brian and said, ‘What is this? I don’t know how to sell this. This is crap. This is terrible.’”

“So the fact that Brian was willing to stick to his guns and didn’t make me do things that made it more like a traditional superhero comic and instead leaned into what it became…I mean the book wouldn’t exist without Brian,” Waid said. “Frankly, the character probably wouldn’t be remembered without Brian.”

Augustyn left the title with issue #16, as he cut back on his editorial work in pursuit of freelance writing work. Ramos left with issue #25, leaving Waid by himself. It wasn’t like that for long, as the writer departed the title with issue #27. When I asked Waid why that was, the answer was simple: because Ramos left.

“I mean it was me and Humberto and that was the team. And so it felt very much upon leaving like I don’t want to keep slugging away. It feels like it has so much of Humberto’s brand to it and it was so much fun working with Humberto that it, I don’t know,” Waid said. “I mean it’s really the same reason I left Fantastic Four when Mike Wieringo left because that’s the fun of it.”

Ramos felt the book started losing its identity to a degree after Augustyn departed, as DC was trying to make Bart a bigger part of its universe. Without its original editor as a buffer, Impulse became more connected to crossovers and other appearances and “less of the kid that we first conceived in the book and more close to a team superhero,” Ramos told me. It was still fun, but not quite the same for him. With Waid planning on leaving eventually, Ramos chose to make his exit with issue #25, a traditionally big number for superhero comics.

“To me, the people I work with (are always more important) than the characters I draw. And Brian and Mark are not only my friends, but in many ways my mentors, because I was just a kid when I was drawing that book,” Ramos said. “And so I was following their lead, I was loyal to them, and I honestly didn’t want to be on a book where they weren’t.”

Waid expected the title to be canceled in short order after he and Ramos left, but incredibly, Impulse lasted for 89 issues, 62 issues after his departure. The character was popular, and so an assortment of other creative teams carried Bart forward into the post-Waid, post-Ramos era. Interestingly, if you go on the ComicVine page for the volume, you might notice something unexpected: neither Ramos nor Waid are amongst the ten most prolific contributors to the series, the only one Impulse ever carried.

And yet, when I revisited Impulse, I remembered the moments Waid and Ramos brought to life just like I was 11, 12, 13 years old again, crystallized in my brain in a way that only the most influential things can be. Those other issues? Lost to the sands of time, despite still owning the lot of them. That isn’t meant to besmirch the contributions of others, but even as a kid, I knew that Waid and Ramos weren’t just another team on another comic. They were the ones who defined that character forever.

It doesn’t help that Bart Allen has long been a mystery to everyone who didn’t originally work on the character. Tonally, the character has been all over the place since that initial run, sometimes being far too broad and silly and other times being way too serious. It often feels like cover bands versus the original artist: you still recognize the song, but something is missing. While Waid isn’t one to check in on characters he’s left behind, he had a theory as to why so many struggled with Impulse in particular.

“They just tend to age him up in their heads. It’s a very fine line, but there (are) so many sides to Bart,” Waid said, specifically citing how Bart is physically one age and emotionally another. “I don’t think people are capable of writing a character that is so guileless. I think that’s really it. People just don’t know how to write a character that is so totally without guile.”

Augustyn believed part of the problem for others was that first team, appropriately, “caught lightning in a bottle,” adding that their run wasn’t “like any other comics being produced or even (being produced) now.” He cited a fill-in writer’s efforts during that initial run as an example. This writer stepped in with a solid premise, but there was one major problem: there were too many thought balloons.

“Bart doesn’t think that much,” Augustyn said. “In fact, Bart doesn’t think at all. He acts. He never explains himself because he doesn’t see a need to explain himself. It makes sense to him.”

By 2003 – six years after Waid and Ramos departed – Bart Allen became the character none of the creative team wanted him to be: Kid Flash. By 2006, he was The Flash. By 2007, he was dead. And sure, the character came back to life, as they always do in comics. But in some ways he’s never really lived since Waid, Ramos and Augustyn all left the title. It has been a struggle to find a place in the DC universe for Bart Allen or Impulse or whatever you want to call him, especially after the return of Barry Allen. 21 It makes sense. If you could define DC’s comics by anything since around 2004’s Identity Crisis, it’s by its rather dark nature. And what space is there for a character of pure, joyous light like Bart Allen in a universe like that?

It’s only fitting that the original run has been a struggle to even reprint, as Waid shared that the Impulse omnibus that DC was going to publish last year has been delayed for an undetermined amount of time because the way comics from that era were produced makes them look awful when expanded to omnibus size. Even recapturing that era in a reprint is a problem for DC.

Augustyn did tout one person who finally understood Bart Allen: Brian Michael Bendis. In the Young Justice relaunch for Wonder Comics, Bendis clearly appreciated and understood what made Bart tick. Augustyn even shared that he told Bendis that until him, “I don’t think anybody understood Impulse.” Artist Patrick Gleason equally jived with the character, as his early work on that book – he bounced to Marvel on an exclusive shortly thereafter – was the closest anyone has ever gotten to recapturing Ramos’ energy. It was truly great to see.

That’s especially the case because to this day, the character is still beloved by some, including the original team. Waid and Augustyn are still fond of their time with Bart, and Ramos told me quite simply, “Impulse made my career.”

“I was another artist, another up-and-coming, struggling kid trying to make a career, trying to establish himself as an artist,” Ramos said. The artist always had designs on drawing Amazing Spider-Man, and it’s his belief that Impulse gave him that opportunity.

“Being the guy on Impulse made me the guy on Spider-Man.” 22

It’s not just that team, of course. I’ve spoken to a fair few creators over the years whose love of comics is partially defined by Bart Allen, just like me, with the work of Waid, Ramos, Augustyn, Wieringo and others playing a crucial part in their love of the superhero genre. I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s more widespread than what I’ve heard, as you can see the DNA of Waid and Ramos’ Impulse in superhero titles from throughout the past decade and to today.

I’d love to see the expansion of the role of Bart Allen at DC, as the character in his original configuration just works, and works well. So would the character’s original writer, as Waid sees a fit for the character in titles for the YA/middle grade digest lines DC produces, saying it “baffles” him that we haven’t seen it yet. Maybe it can happen with noted Impulse opponent Dan DiDio out at DC. But who can really guess if it will, especially in a time where the industry and world is in such disarray?

There’s undoubtedly an opportunity there, though. Bart Allen is a character with a real timelessness to him, and one that few characters can match. That’s proven by the fact that his origin story, created 25 years ago in an era with barely any real Internet to speak of, has almost become a reality in our own lifetimes. The version of Impulse Waid, Wieringo, Ramos and Augustyn developed in the mid ’90s had roots in science fiction and the 30th century, but since then has become something singularly unexpected: the perfect superhero for 2020, and a reflection of our endlessly changing world.

As of last Tuesday, March 31st, to be precise.↩

This was during a time where Barry was living in the 30th century, right before he disappeared during Crisis of Infinite Earths and also right before his essence becomes the lightning bolt that gives him his powers, because time travel in comics is insane.↩

Shouts to inker Wayne Faucher and colorist Tom McCraw as well!↩

For collectors out there, his first appearance was technically in The Flash #92, but his cameo was in #91.↩

Impulse was, in many ways, my very first hang out comic.↩

In 1995, most of our awareness of the Internet stemmed from endless discs we were given by America Online in magazines and our modems screaming at us as we logged on. It was not a great time for the Internet.↩

Quick fun fact for you: in a role reversal, Waid edited Gotham by Gaslight, a comic Augustyn wrote and Mike Mignola was the artist of. It’s a well-known comic, but mostly for the Mignola art. I found Waid editing his pal Augustyn on it to be a charming note.↩

Greatest Flash of All Time.↩

This was the excellent storyline “The Return of Barry Allen,” in which Barry Allen “returns” but in actuality it is a younger version of Eobard Thawne – aka Professor Zoom – who convinced himself he was Barry (and looked like him as well). It’s weirder to explain than it is to read.↩

Also because EarthGov was secretly being run by the Dominators, an evil alien race you might know from the comic Invasion! As with all comics, it’s complicated.↩

Temporarily, of course.↩

Waid noted that this was the “same reason Superman wears a cape because it helps show him in flight when the artist is drawing him.” Context!↩

Quick note: Pozner had an absolutely fascinating career, with the editor being credited for also discovering Stuart Immonen, Gene Ha, Travis Charest and Phil Jimenez at this time, amongst many other things he accomplished.↩

I even found an old Wizard article making that direct comparison during my research.↩

I studied Ramos’ art endlessly in my youth. I had designs on becoming a comic artist, and the artist I most wanted to be was effectively whatever Humberto Ramos from 1996 mixed with 1992 Jim Lee was.↩

Again, shouts to inker Wayne Faucher and colorist Tom McCraw as well!↩

This manifests itself several times as Bart straight up trying to tell people he’s a superhero – even in his initial paper for school! – because he cannot even fathom why he would have a secret identity at first. It’s hilarious.↩

There was more than a little wish fulfillment connected to my love of this book when I first read it. I was not cool when I was 12!↩

Which, if you don’t know, is where all speedsters get their gifts in DC comics.↩

Reading this today, I almost took the character as the team’s commentary on the vixens of the era, while existing as a still fitting villain for Bart.↩

The real one this time.↩

He even shared that then Amazing Spider-Man editor Steve Wacker was a fan of Ramos because of Impulse.↩