“I’ve Made the Right Deals with the Right Demons”: Artist Evan Cagle on Bringing The New Gods to Life

There’s just something about Evan Cagle.

When I saw his art for the first time on the cover to the first issue of the BOOM! Studios series Strange Skies over East Berlin, I just knew that, once again, there was just something about Evan Cagle. Now, I’m not always right with those instincts. I’ve been wrong before. But I was more right than I ever could have imagined about Cagle, an artist whose work was great to begin with and has improved dramatically since I first saw it. It’s helped immensely that he’s found a perfect partner for his work, as Cagle has only gotten better and better showcases since he began collaborating with writer Ram V. The guy had the juice already, but when paired with Ram, that duo just makes sweet, sweet music together.

While Dawnrunner, the pair’s series at Dark Horse Comics, was exceptional, their collaboration on The New Gods at DC Comics might be even better. It features Cagle finding new answers to Jack Kirby questions while telling a visual tale of a besieged people, big emotions, and even bigger visuals. Taking on Kirby is a tall task for any artist. And yet, Cagle makes it look easy, as each issue is filled with the type of art that reminds us why we read and love comics. It’s quite the achievement by the creative team, as Ram does what Ram does, colorist Francesco Segala acts as a perfect complement to Cagle’s line art, and Tom Napolitano brings his typically strong lettering work to the page. But Cagle’s visuals 9 are the revelation to me. It’s staggering work by a staggering talent.

So, naturally, I wanted to talk with Cagle about his efforts on the series after previously chatting with him and his writing partner before it launched. I thought I knew what was coming, but apparently I didn’t, so I had to dig into the work with him. That’s what we did recently, as we got together to discuss his background, managing the schedule of the book, its guest artists, and more, before diving into six different pages from the series so far to learn more about Cagle’s process and the decisions he makes on the page.

You can read our conversation below. It’s been edited for length and clarity.

Why comics? What made you want to work in that space after having a career working in other spaces like video games, animation, and advertising?

Evan Cagle: The barrier to entry is so low in comics that it’s one of the few places left that I think a good idea and or good work positioned up front can get you through the door. It’s not true of film. It’s not true of TV. Those things haven’t been true in 50 years. (laughs) And it’s one of the last storytelling mediums that that still is not successful enough to have thick barriers (laughs) between you and Production.

And I love them, obviously. That’s the simple answer. But from a practical standpoint, they were an area that I wasn’t involved in professionally but loved for a long time. And honestly, all my other positions sprang from my ability to make art. And so, in a sense, it’s more essential in comics, l if that makes sense. There’s a lot of static that happens in production between what may start as a concept sketch and what it ends up as on a screen. In comics, for better or worse, that’s not the case.

It’s much more improvisational, in some ways. There’s less editing allowed, there’s no sculpting allowed. It’s much more about, just get it on the page and make it look great. That’s how it is. What you’ve drawn is the final product.

I mean, if Ram or DC editorial weren’t in love with something you ended up drawing, they’re probably not going to get you to completely redraw the page just because that would mess up the process.

Cagle: Yeah. Even if you don’t have a monthly deadline, because it’s so labor intensive. The process takes so much time to begin with. It’s why when comic pages are incredible, it’s mind-blowing to me because it’s almost certainly somebody’s first go. Like, they’ve never drawn that page before. You just can’t do multiple takes. I would love to have gotten a galley copy of Dawnrunner and been like, “I’m going to go ahead and edit this. I’m going to redo page five and redo page 13.” It’s absurd to imagine.

Editing a comic the way that you edit a movie or games, it’s just not possible. And so, when it comes together and really works, it’s just lightning in a bottle.

I was watching a conversation between actors recently, all of whom had worked with David Fincher. And I don’t know if you know much about David Fincher, but he loves doing lots and lots of takes. They were talking about the fact that after he started working on digital, he went from doing 30 or 40 takes to 70 or 80 takes. But when you think about comics, you get one take. That’s it.

The other factor is…we’re going to be talking about The New Gods today, and at least to my knowledge, this is the first time you’ve worked on like a real monthly schedule. So, it’s not just that you are drawing this for the first time. It’s that you have a ticking clock at all times. No pressure, Evan. But that’s a reality of it, right?

Cagle: I mean, look at the closest possible analog to that, which may be theater or live performances of some sort. But even then, you’re talking about having rehearsals and months of preparation. Comics are a complete tightrope walk. (laughs) So, the fact that anybody can make anything worth looking at is incredible to me.

And a lot of times, I just didn’t have the time to do full character turnarounds, all the things that I love to do for my creator-owned stuff. It’s just not possible on a monthly book. You may get a last minute, “We have to have this character in there,” and it’s like, okay, well, I’ll take lunch to figure out how to draw that character, and then I’m off, because it’s due tomorrow. (laughs)

I know you’re not going to be able to bring out the best work you could possibly do, but do you feel like you’ve managed to figure out the efficiency necessary for you to be happy with your own work under that schedule?

Cagle: Partly yes. Partly I’ve been able to adjust my style in a way that allows me to spend time on what I want to spend time on and to…I won’t say rush, but to spend less time on things that are interstitial.

I wish I could be like a Mike Allred or Chris Samnee, this sort of clean, beautiful, economic line work. But it’s not in my DNA. I am definitely a maximalist, which hurts from a scheduling point of view.

But I think I’ve made the right deals with the right demons. (David laughs)

How much does the structure with the guest artist 10 save you?

Cagle: It saved my bacon quite a few times. I have to credit Ram with that. He never does anything for no reason. I was initially reluctant to jump on New Gods. It’s a monthly, it’s a series that I wasn’t familiar with…there were all sorts of reasons. And one of the reasons that I kept coming back to was it’s a monthly…I just didn’t know that I could handle that grind. And he was like, “What if we get other people to do pieces of it?” I was like, “That sounds horrible.” Every time I come across that in the wild, it pulls me out of it so much.

But he went into it with the notion that these wouldn’t be fill-in pages. The narrative is designed around the fact that other people are going to be taking over aspects of it. So, the gulf in styles, the shifts…all that is taken into account.

This page is Orion and our guy Scott Free hanging out on a bench. And I want to start with this one not because it’s the best look at your design for Orion, but it’s where I’m going to bring it up anyways. As part of this project, you redesigned several of the New Gods. We talked about that before. Redesigning Kirby is always a tall task.

Cagle: Yes.

What guided you as you redesigned characters like Orion? Because as you well know, people are going to have opinions. What made you want to go this direction with Orion and the other characters in the book?

Cagle: First of all, Kirby is working with an idea of sci-fi and futurism if I can call it that that comes from a point in history that is super specific and decades behind us. If those designs go unchanged, they invariably look retro. And so, what I had to weigh is if I’m slavish to the original design, it looks retro. But that is contrary to his intention for design, which is not to look retro. He’s not deliberately looking retro. He wants to look futuristic. He wants to evoke sci-fi in shorthand. And so, to my mind, it was more important to use his same principle, his intention, rather than his design.

There’s maybe bit of a subtlety there, but I think his intention with this is futuristic and sci-fi. And from his vantage point in history, that’s what futuristic sci-fi looked like. And so here in the future that he imagined, I am reimagining that and saying, from my vantage point in history, this will be futuristic and sci-fi. And in another 40 or 50 years when some other loser comes along (laughs) to redesign my work, it’ll be the same thing, right?

Hopefully they won’t stick to my designs. They’ll do something futuristic and cool.

Why were Mister Miracle and Big Barda left alone?

Cagle: That I think is more a matter of continuity and consistency because they happen to be a couple of characters that get a lot of screen time in the DCU.

From an editorial standpoint, it’s a lot less to ask for when you say, “We’re going to redesign a fourth of the cast” as opposed to “We’re going to redesign half of the cast.” And frankly, they’re great designs. Those are two designs that I think still actually represent his intention in a in an honest way. I don’t think there’s anything about those designs that are inherently anachronistic. They don’t make me feel like this is this is a vintage design. There’s no reason somebody couldn’t come up with some Mister Miracle like outfit or Barda like outfit today.

This page does highlight one of your low-key strengths. I only say low-key because you have several more high-key ones. (Evan laughs) I love how you draw Scott Free here with his head tilted all the way back in the first panel., and then in the third and fourth panels, he kind of lolls his head back and tilts it over instead of actually turning his head completely. It is amazing and very simple character acting that really works.

How do you figure out the character acting side of the job? Are you a photo reference guy? Is it very instinctual? What guides you on that side of things?

Cagle: I used to be an animator. I have this conversation with Ram a lot. (laughs) The big difference between comics and animation is the inbetweens. These are basically key frames. If I were directing this as animation, this is what I would give as my key frames for an inbetweener. 11

In terms of where the motion comes from, I act everything out absolutely ridiculously. I’ll get up and prance around and contort myself and do whatever just to figure out what that motion is. In so doing, I find my keyframes. I find the extremes of a position to imply emotion where I can’t…you know, obviously I can’t have in-betweens (laughs), so I only get the extremes.

So, you do photo reference?

Cagle: I do some photo reference, but I think more useful than photo reference is actually acting it out.

So, you act it out and then visualize it in your head and just go from there?

Cagle: Yeah. So, in a page like this where it’s not action heavy, I want the strength of it to be in the blocking and the acting. There’s nothing flashy happening. There are no great big arcs of motion in here. I’m not doing anything fancy with the camera. And so, if I’ve got the script in front of me and I cue it up in my head as it were and then act it out as those characters, then I see immediately what needs to be where.

Another thing I like about this page is how the top third of the page is split into two panels. It doesn’t have to be. They’re technically a continued image. Why do you split it like that? What makes that the move? Is that a Ram thing? Is that a you thing? Where does something like that come from?

Cagle: My hope is that you read gutters as time. And in this case, it’s sort of implying a camera pan over that time. So, if this is a single image, then that’s my shot. It’s just a mid on Scott and Orion with his back to us. If it’s a dolly or if it’s a tracking shot somehow, and we begin with Scott and then we move slowly over to the right to reveal Orion standing there, that says something different.

I think it matters in an imperceptible but important way that you register even though you may not realize you’re registering it.

I completely agree. I think it’s a great decision by you.

That said, you are speaking in an atypical way for a comic creator. You speak about it like an animator or a filmmaker. Do you think about comics in filmmaking terms?

Cagle: Yeah, but not just that way. Obviously without motion and time, which are films’ great strengths. Without those two things, it’s not a one for one analog, right? You can’t just think of it cinematically.

So, I do think about it cinematically, but I also think about it in terms of composition. I think about it in terms of blocking for what’s the easiest read. I don’t want anybody to spend five minutes reading these comics through. But people will. Some people will only spend five minutes and flip through it. And even at that pace, I want things to be readable.

One of the criticisms that I got for Dawnrunner was a lot of the fight scenes were too kinetic and there’s just too much happening. But I’m not a complete fool. You have to believe that on some level, I want you to read that as noodle soup. I want you to read that as a mess. Should you spend a lot of time on it and figure out where all of the choreography is happening and where all of the bodies are impacting one another and all that stuff? Great. And if you don’t, what you come away from any given frame of combat in Dawnrunner is the idea that so much is happening, so many big things are hitting each other, and so much shit is flying around that it feels upsetting and kinetic.

So yeah, I think about this stuff a lot. I think about pacing and breaks and where to let the art breathe and all that stuff.

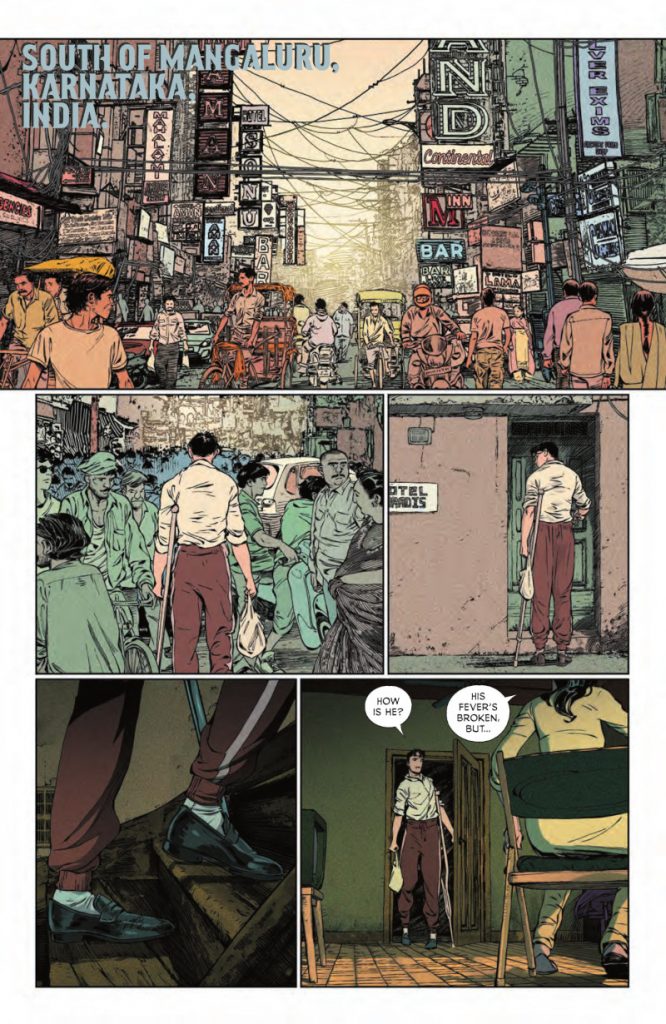

You talked about putting a lot on the page. The top panel on this page has a lot going on. Not everyone excels at this, but you are great at drawing dense and detailed panels and pages. You are particularly good at drawing locations and settings. You always go the extra mile to bring those to life, and I really appreciate that about you. There’s a version of this that does not have nearly the number of signs or nearly the number of people there.

Cagle: It’s India. (laughs)

I’ve been to India (Evan laughs), if you didn’t have that the verisimilitude would be destroyed for anyone who’s ever actually seen India. But what is your approach to bringing something like this to life?

Cagle: So, this is a great example of what I was just talking about, right? I want you to be overwhelmed in the way that you undoubtedly were overwhelmed walking around in India. Obviously, it’s great if you spend a lot of time on this panel and look at it and try to figure out where all the bodies are and what they’re doing. But I also want you to look at that and be like, holy shit, what a mess of visual information, which is consistent with all of the research Ram sent me when we first started doing the India locations. And the thing that keeps coming up over and over again with particularly urban Indian settings is just the visual overload.

So that’s part of it with this image is I want you to get a little bit smacked in the face and like, holy shit, what am I supposed to pay attention to here? I guess I just have a high threshold for what I think makes a setting compelling. And so, maybe I just keep going when other people might not keep going. But I feel like, as you said, there’s something about this image that feels more like the real thing than had I simplified it. And it’s great that I’ve got Ram who can look at an image of India that I’ve done and be like, “Eh. Needs more.” (laughs)

I mean, he’s never told me to back off the detail, but he could.

I feel like the thing that makes this image isn’t the foreground but the background textures you put in there to imply more city. (laughs)

Cagle: It’s just line goo.

It’s line goo, but it makes sense. It computes in your head as a continuation. Most artists would not draw the level of foreground detail, but at least 98% of them would leave out the background. They would leave that part out.

Sometimes when I see what you draw, I feel like I know that you enjoy drawing it. Do you specifically like drawing locations and settings?

Cagle: Not specifically. Maybe this is just the cinematic part of my brain, but I’ve got to get myself over the hump of the suspension of disbelief. I want you to feel like these are credible places, at least once. It doesn’t have to be every time. It doesn’t have to be every panel. But if at least once I can get you to say, “Okay, I see where I’m supposed to be. I see where this is where this is happening.”

And yeah, I guess my threshold for that is just a lot higher. I want it to feel real. I want it to feel credible.

So, it’s less about the “what” of what you’re drawing. It’s more about your ethos as an artist, to put it in the fanciest way possible.

Cagle: Maybe. Obviously, some locations are more visually interesting than others. Like I don’t think that I’d be so interested in doing a crowded strip mall outside of Houston. (David laughs)

Downtown Lawrence, Kansas. (Evan laughs)

Cagle: No offense to Houston or Lawrence, Kansas. I’m also in a privileged position that Ram and I know one another well enough that he has a sixth sense about the sort of stuff that I’ll enjoy drawing and is able to see things like that.

The next pages I want to talk about are not a spread. They’re actually separated by page turn in the real issue. At least in my mind, though, they were not separated by a page turn. But they work together and absolutely rule. (Evan laughs)

The thing I really love about this is the fact that in the bottom left panel, you have a big beam of energy being shot up to the right. And then on the next page, that same beam of energy is hitting from not the same angle, but a similar angle. When you are drawing an issue, do you think of pages, even ones that are separated, in a connected way? Because I have to imagine you went into this thinking, “I want these two to play off of each other.”

Cagle: Yeah. Which is a thing that I hate about the monthly grind is like, I’m going to do all that work and then I’m going to get hit by an ad. (laughs) And I never know where it’s going to happen. I’m pretty safe within the first four or five pages, but then it’s anybody’s game. An ad can come out of nowhere and just kneecap whatever composition I’ve come up with.

That is why I love trades, because all those ads disappear and you suddenly get that these two pages are meant to go together in some way.

I love this one.

Cagle: Yeah, I love these two pages together.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

As well as the work of guest artists like Stipan Morian, Andrew MacLean, Jorge Fornes, and beyond.↩

Every issue of The New Gods features one guest artist to draw a sequence of at least four pages, and sometimes many more.↩

Per D23, this is an “animation term for the artist who creates the drawings in between the extremes of an action drawn by the animator, assistant animator, and breakdown artist.↩

As well as the work of guest artists like Stipan Morian, Andrew MacLean, Jorge Fornes, and beyond.↩

Every issue of The New Gods features one guest artist to draw a sequence of at least four pages, and sometimes many more.↩

Per D23, this is an “animation term for the artist who creates the drawings in between the extremes of an action drawn by the animator, assistant animator, and breakdown artist.↩

The villains of the story that are after the New Gods.↩

The leader of the Nyctari.↩

As well as the work of guest artists like Stipan Morian, Andrew MacLean, Jorge Fornes, and beyond.↩

Every issue of The New Gods features one guest artist to draw a sequence of at least four pages, and sometimes many more.↩

Per D23, this is an “animation term for the artist who creates the drawings in between the extremes of an action drawn by the animator, assistant animator, and breakdown artist.↩