“I Want to Stop Time”: Cartoonist Renaud Roche on Bringing Lucas Wars to Life

Every year brings a fair few unexpected hits for me as a reader, as varying comics and graphic novels come out of nowhere to blow me away and storm up my end of the year list. This year’s going to be filled with several of them, I think, but you can be assured of one thing: Lucas Wars will be one of them.

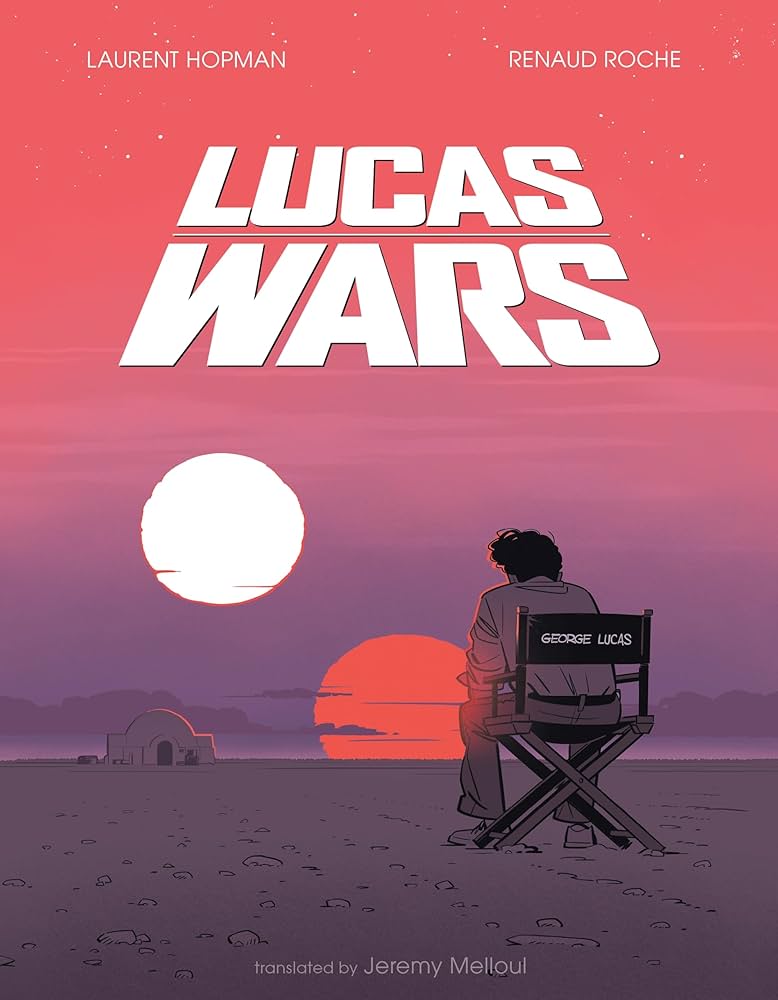

This 23rd Street Books release from writer Laurent Hopman and artist Renaud Roche was a sensation when it originally was released in France, but First Second’s sister imprint made sure it received an English translation. I’m glad it did, because this look at George Lucas’ life and the making of Star Wars (the first film, not the franchise) is tremendous. Not to discount Hopman’s work, but the biggest reason for that is Roche. That artist is a revelation in this book, as he delivers a cartoony style that focuses on storytelling and impact above all, bringing these events and its characters to life perfectly. The incredible thing, though, is this is the animation veteran’s first comics work, making the whole thing that much more astounding.

As soon as I read Lucas Wars, I knew I had to talk with Roche, and we’ve been planning that ever since. The artist had the little consideration of wrapping and releasing the book’s sequel between then and now — it’s out now in France as Les Guerres de Lucas Episode 2 — so it took some time to put together, but we recently were able to sit down to chat. During this conversation, we discussed his own background with comics and how he made his way into the medium, before we discussed five pages from Lucas Wars and everything that went into bringing those to life. It’s a great chat with an ascendant star in the field, and someone I suspect we’ll be hearing a lot more from going forward.

You can read it below. It’s been edited for length and clarity.

As far as I understand, Lucas Wars was your first comic project. What was your personal history with the medium of comics, whether that’s bandes dessinées or anything else? Has that medium been a big part of your background as a reader and as an artist?

Renaud: Yes, indeed. There were three phases, I guess. When I was a kid in France, I grew up with the classics of Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées. It was Asterix, of course. It was Tintin, but maybe a bit less. I loved some Spirou, some Gaston…the main stuff.

And then…I was born in 1980, and so in the early 1990s there was something happen in France that we called the manga tsunami. (laughs) It was so funny because it was really because of a TV show called Club Dorothée. She was a host during these big shows on Wednesday, which was mostly kids’ day, because you are not supposed to go to school on this day in France. And so, they were on TV almost the whole day, from seven in the morning until six in the evening. There may have been a pause for the news in between, but it was a crazy and very diverse show with some music and some games but mostly cartoons.

And the thing is, at that time they made a deal with a Japanese cartoon studio because it was very cheap to buy and broadcast them on TV. And so, we had like all these crazy cartoons like… I don’t know the name actually in English, Chevalier du Zodiaque, like the Zodiaque Nights. I don’t know if you had it back in the day.

I guess it’s Saint Seiya, Knights of the Zodiac.

Roche: Yeah. This and Dragon Ball of course were huge. I was really the target at that time. I was 11 or 12 and so I had jumped fully into it. Especially Dragon Ball, which was my main focus at that time. I was drawing a lot like Akira Toriyama because I was very impressed and passionate about it. It went like this for a few years. This was the period of life when you can really dive into a very specific style and just be stuck into it, especially if you’re an aspiring artist.

I’ve seen that with other talented artists in my school years. They were good artists, of course, but at some point, they just mimicked a specific manga style, and they stayed in it their entire career. That’s good, in a way. If you really like it and want to do this, but I think it’s less personal than others. And I could have gone this way, but I was saved by the third phase of my connection with comic books. (laughs)

It was a bit later. I was a teenager, and I was spending some holidays at my grandma’s in a small town in France called Dijon. And so, I was a bit bored, sometimes. There was not much to do. (laughs) But there was a public library. I read a lot of comic books, and especially the Heavy Metal era, the magazines with the French sci-fi masters like Jean Giraud, Moebius, of course, (Jean-Claude) Mézières, (Philippe) Druillet, that generation of amazing artists. Especially Moebius. Moebius was another big crush and a big artistic and visual shock for me. I read almost all I found at that time from him.

It’s funny because I was 17 or something, and I reproduced what I’d done with manga and Akira Toriyama, but I started to draw like Moebius. I was trying at least. It started to really impact my style. I guess it’s a very classic way to evolve as a graphic artist, and I’m not the only one that at some time, especially when you’re younger, really tried to reproduce something because you are so influenced by those talents. It’s a way to understand, you know.

But I think that finally what happened, especially after I detached a bit from comic books and I focused more on animation. I went to this school called Gobelins in Paris, which was really a school about feature animation. And then I started to mix all those influences in a way.

Something thing I discovered much later were some comic books. Not much, but especially Mike Mignola. At some point, it really merged in a way and made a weird mix inside me. Maybe you will tell me that when you look at my style, you cannot really say, he was so influenced by comics or so influenced by manga or there might be a bit of both of traditional bandes dessinées too. I have no idea actually what it looks like (laughs), but I think when you look at all those influences and different faces and sequences it makes more sense, maybe.

We’ll talk about style here in a minute, but I wanted to get back into one thing first. Lucas Wars was your first comic project. You have previously worked in other art forms, from animation and storyboarding to editorial illustration and visual effects. Most people don’t make that transition. Most people don’t just jump into another thing altogether much later in their life. (Roche laughs) What made you want to make that transition? Was it just because the opportunity was so appealing with this project?

Roche: I had some (comic opportunities) approach before and the condition was not met for me, both on the artistic level or the financial level. I don’t know how it works in the States, but in France it can be a very precarious job because…now the comic artists are given a contract with a certain amount of money which is for all the job. So, if you have to do 50, 100 or 200 pages, it’s almost the same money. And it’s supposed to be an advance on the royalties and the future sales of your book.

But it changed because I guess 20 years ago maybe, you were a French artist, and you were paid on every page. If you were doing one or two pages per week, you had a salary for those pages. So, you were literally paid for your work. So now you’re paid on the potential of sale, which is very weird and sometimes…okay, when it works well, when you sell a lot, it’s great. But the market, in Europe and especially in France, it really exploded these past few decades because…the good part is there is a lot of more variety. A lot of different kinds of formats, of subjects, of graphic styles. That is amazing.

The bad side is that there are something like 5,000 new comic books every year. 10 or 20 years ago, it was like 500. Obviously, the number of readers grow a bit too, but not that much. So, it means that it’s a very precarious job when you are not well supported by your publisher or already famous. I had a good situation in animation or storyboarding as an independent artist.

So yeah, I was thinking about it but not on every condition, and surely not on every kind of project. I was saying to myself, if I go there, it will be for my idea, my stories, and something that I care so deeply that maybe I sacrifice to not live well for a few years. (laughs) And to be fair, my childhood dream was comics. It’s just that I discovered feature animation quite late as a late teenager. That’s when I discovered I could make a living by doing cartoons. That’s when I shifted my focus because it became more appealing to me.

But there was always this idea of maybe someday I could try to do like one or two comic books. And it happened this way because they contacted me about Lucas Wars and it was a good offer both on artistic level and financial level. So, I jumped.

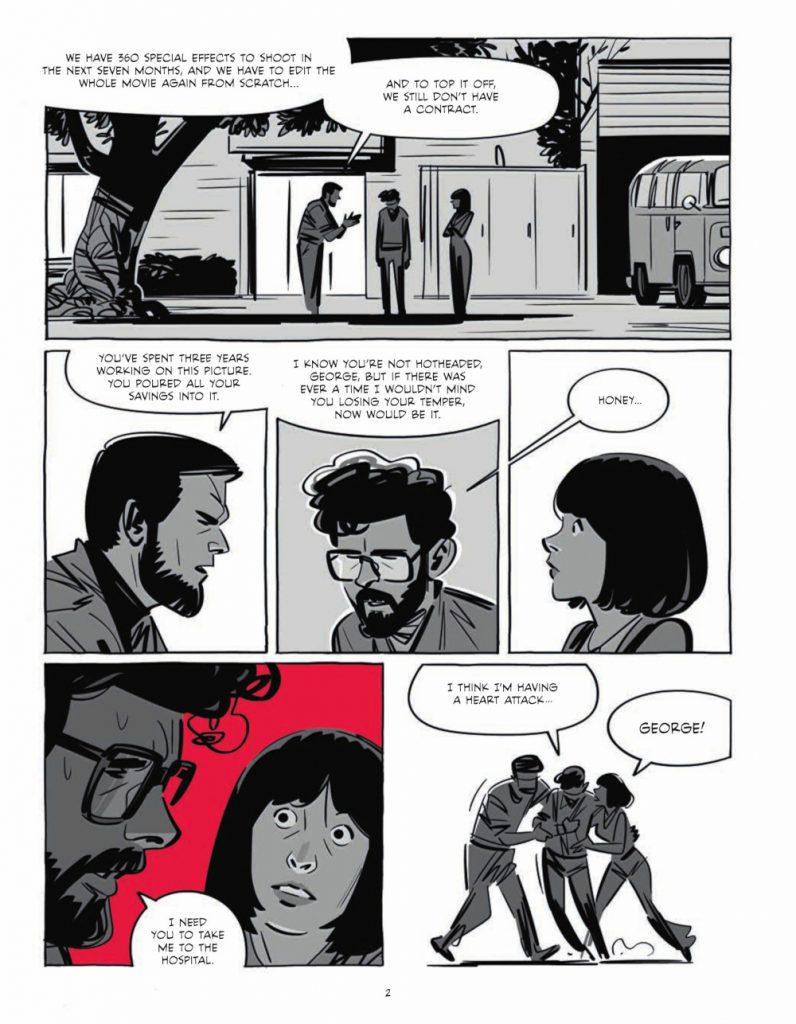

Let’s talk about the first page. This is where we’re going to bring in the style of it all. This is an early page from the book. What you use in the actual final version of Lucas Wars is not like your initial sketches at all. They were much more realistic. I’m curious as to how you figured out the right style for this book because it ends up being a little bit more spare in an Alex Toth sort of way, a little bit more cartoony, a bit more gestural, all in a very effective way. When you go into a project like this, is it less about what your personal style is but, “What does this project need?”

Roche: For sure. I guess there are two ideas. One is to fit the project’s needs and its themes. I knew that it was at least 200 pages, so there was a lot to draw and also a lot of different kind of stuff to draw. Also, to draw reality more in a documentary way, I was not totally free to express my style and create everything.

The process was quite organic and instinctive because, yes, of course the first sketches are more realistic because I was also trying to analyze from sources. I was more focused on details and to really catch the essence of those people mainly. And then after that, I just let my more usual style, especially the one I use in storyboarding, when you have to be more efficient in your style and dynamic, I let it come back and flow. And I guess I mixed a bit because my storyboards are rougher, even if it’s still a rough style in a way.

It was just trying to put a good balance between something nicely crafted and realistic. The last panel is actually a good example because when you have to focus on the faces, it is a bit more detailed and a bit more delicate in style. But the last case is really, it could be a drawing from a board. And I really tried to stay very rough and to just express the urgency of this moment when he’s starting to fall precisely for this. I wanted to stay very rough and to have some lines that support the action and the movement.

Even if it means exactly that in this case, to remove some details, especially the eyes, or…I don’t know, some features of the clothes and stuff like that. I didn’t need those because I wanted really to express the urgency of this moment.

You do that in the first panel too, right? You look at George Lucas, and you can’t see his face and you can’t really see like details of him, but you immediately know how he’s feeling because of his hang dog look. (Roche laughs) You do an amazing job with that kind of thing.

But I do want to touch on one thing you were saying. You were talking about how when you were initially figuring out the characters and everything, you were doing the more detailed studies. Do you find that doing those more detailed studies can help unlock the characters for you?

Roche: I think it’s basically like when you are taking notes at university and you have a theoretical course. The teacher is speaking, and you have to draw by yourself. We always say that the process of drawing it by yourself helps you better memorize what was said. It’s not the same at all that if you were here and you bring the notes of a friend and you try to understand what he wrote during the course. It’s not as efficient as doing it yourself.

So, I think it’s in the same way. I had to really draw several faces from those characters from sources to try to start to understand the volumes and the main features that will be synthesized and simplified later on. I guess it’s not so long actually because at some point when I had a good balance for George, who was the main focus of course, I was able to adapt that look for every character in a way.

This is a nearly 200-page graphic novel. That is a lot of sustained work. How much does the length of the project impact your approach? Do you need to be conscientious of the fact that you have a lot of pages to draw and so maybe that affects your style because you can’t go so in depth because of that?

Roche: Yes, but I was aware from the start because…I like to draw the whole thing rough. My publisher would say it’s not quite a rough, because it’s very much already drawn. It’s not like potatoes. 5 I wanted to do potatoes first to do the breakdown of the pages, but I was absorbed and dove into it, and I cannot stop myself from drawing more detail sometimes.

But this is a way to really have the whole story and to do the main changes and adjustments at this step. And then, only after all this is in place, to do some more inking. And it’s funny because on this one, it was my very first one, so I guess I was more cautious. I had like three steps. One quite rough, another a bit more detailed, and a third part when I would redraw some stuff and make retouches at the end.

I managed to remove one of the steps for the second book, you know, because I was more confident. I trusted my first step more. I am lucky to have a rough that is already quite clean in a way. It can look already like an inked final drawing. And so, in the second book there are finished drawings that are actually the first drawing.

It’s basically the rough, or maybe I adjusted some little details. But the main drawing is the same. It’s not the case for everything, but because I wanted to keep this energy…sometimes the first drawing is the best one actually, and if you redraw it, you sometimes lose something.

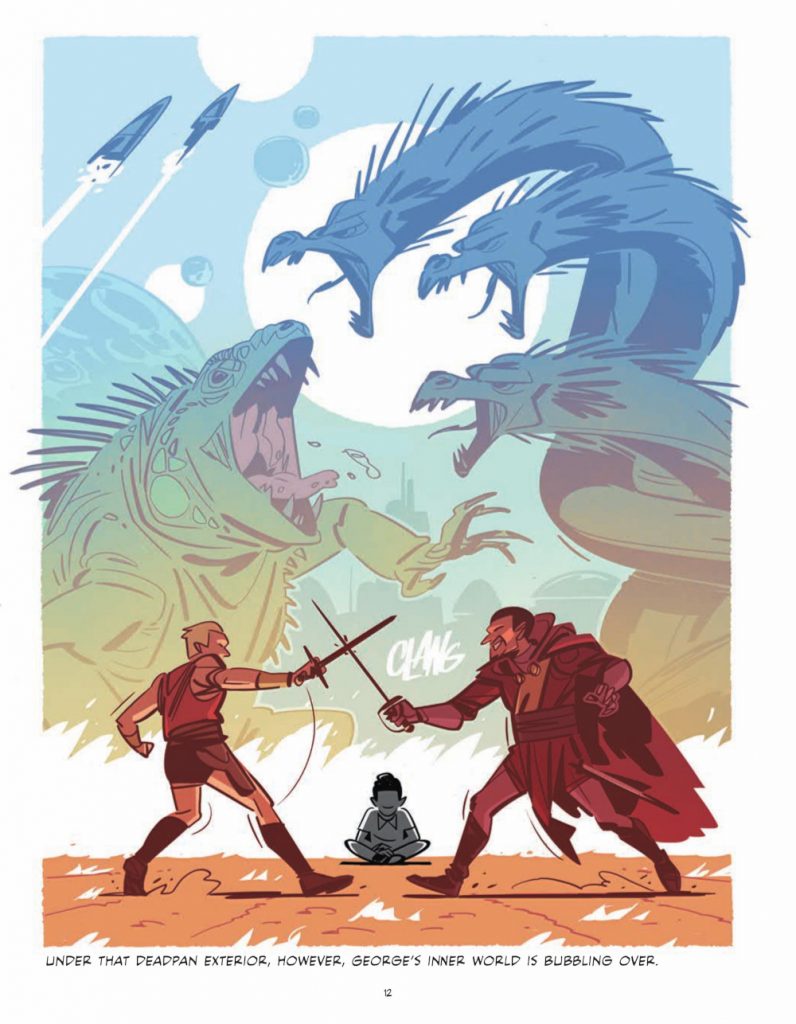

This is early on. It’s George watching one of his stories and falling into it. I want to talk about this because of its color. Color is interesting in this book because for the most part it’s black, white, and grayer tones. But occasionally you have a page like this where color is much more prominent. What were your goals for the color in Lucas Wars? What kind of impact did you want it to have?

Roche: I wanted to have another narrative layer on top of the storyboard and the mise en scène in a way. 6 When I signed up for the project, we were planning to do it all black and white. Very early on, I realized we could add something. I was not very confident in the idea to do it all in color. Because while I really think I have progressed with color these past few years, I never learned it. I never studied color mathematics (laughs) and all those rules you have to master.

So, I really wanted to do it by myself, but I always considered myself to not be a very good color artist. The line and the drawing are where I know I’m strong. This is where I can really have something to say. But color is always more laborious for me. So, early on, the idea was to say, okay if I put in color, I will not put it all over the pages. So, I need to choose where. It has to make sense. It has to have a narrative purpose.

So, there were different ideas in different other scales. It can be on the scale of one panel, because you want to focus on one object and you really want to guide the reader in this specific direction. It can be when it refers to everything from the imagination. So, this is the perfect example for this page, for example. Everything fictional, everything coming from the mind of someone, most of the time there is color.

But it can be also on the scale of the full book. Maybe you realize that there is this yellow color, which my publisher and I called fate yellow, because the idea about this, is basically the yellow that you will find at the end on the Star Wars logo when they look up and they see it on the Chinese theatre that has this huge Star Wars logo. Every time I put this yellow, it means that something happened in George’s life that will change his destiny.

It’s never a choice. It is always something that happens to him. It can be the crush. It can be when he meets someone that will become important. It can be when he discovers a book that will have a lot of meaning in his thinking. So, every time you see this yellow color, it had a very important meaning about his destiny.

So, voila, I think it was the idea to just give another layer and sense for the story.

That brings up something that I’m not entirely clear on. As far as I understand it, Laurent Hopman wrote the script. But you were the only person who did an afterword in the English version of the book, which made me wonder what the actual process was like? Once the script was done, was it you just figuring out how to bring it to life effectively in isolation? Or were you working with Laurent to figure everything out?

Roche: You have to know that Laurent is both the scriptwriter and one of the publishers too. He has this double hat. But it didn’t change anything in a way because we were in constant contact as a publisher but also as a scriptwriter because he was very open and very able to discuss and adjust with me a lot of details. He was writing a script, and it was already written with descriptions of everything that had to happen in the panels and the dialogue.

But sometimes…I guess quite a lot of times…he was not quite sure. I had to make the script mine and adapt and sometimes transform some of the details. And sometimes he was writing in only one panel, and I was saying, no, we need two or three to make it very clear and to make it more vivid. And sometimes it was the other way. In these two cases, we can merge into one or we can remove this text because the picture will tell enough. We don’t have to add more text on top of it.

So, it was a constant process while I was doing the rough version. Every week I was sending pages, and I was explaining my changes to make him understand and to see if he agreed. We were constantly doing this back-and-forth discussion. And even when I was working on the final pages, it was still going on. So, the script evolved a lot, and it was always an exchange all the way.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

Meaning rough shapes meant to represent figures with little detail.↩

Or how everything is arranged in a scene.↩

Meaning rough shapes meant to represent figures with little detail.↩

Or how everything is arranged in a scene.↩

Meaning rough shapes meant to represent figures with little detail.↩

Or how everything is arranged in a scene.↩