“Storytelling is the Most Important Thing”: Stefano Caselli on His Journey and the Art of X-Men Red

Stefano Caselli is underrated.

That’s not to say that Caselli doesn’t get his flowers. People know the Italian artist can tell a story and deliver an impact with the best of them. It’s just the guy has been doing exemplary work for two decades, and doing so on A-list Marvel titles like Avengers, 14 Invincible Iron Man, 15 and Amazing Spider-Man 16 while launching new characters in books like Avengers: The Initiative and Secret Warriors. My vote is that until he’s widely recognized as one of the most consistently solid artists working at Marvel, that take will stand: Stefano Caselli is underrated.

That said, the tide may be turning in terms of proper recognition of late. His recent run on X-Men Red — my pick for the best Marvel title going these days, at least in part because of Caselli’s work in its first 11 issues — found he and writer Al Ewing and colorist Federico Blee regularly lighting the world on fire 17 with their work. It’s some of the finest work of Caselli’s career, as he found partners in Ewing and Blee that fit him well, and moments both big and small have stood out thanks to the artist’s tireless, thoughtful craft. It’s been great to see as someone who reps hard for Caselli — but we can always go further. So, that’s what we’re going to do today in an art feature interview, as we celebrate his work in this conversation and help readers better understand what goes into it.

I chatted with Caselli recently via email to dig deeper into how became the artist he is, exploring his work, his art background, and career path before we dive into an array of pages from X-Men Red and the decisions that led to each of them being the knockouts they are. It’s a great chat with one of my favorite superhero artists working today, and I think you’ll enjoy it. It has also been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start with the basics. What came first for you, comics or drawing? And what made sense to you about pairing your love of each together into drawing comics for a living?

Stefano Caselli: I think that like any kid in the world, I started just drawing. I spent days copying the heroes I watched on TV. But at a certain point I started making my own adventures. I remember that my first story was a G.I. Joe comic, in which I introduced a character created by me, and then I did an Hokuto no Ken 18 story. Honestly, I can’t remember what happened there, but I think telling stories is an inner need for any kid and I found that drawing was the fastest way to do it.

You’re from Italy, a country home to some of the true legends of comic art and some remarkable modern talents as well. Once you realized you wanted to make art — and maybe comics — for a living, how did you work on developing your skills? Did you go to art school? What was the road to developing your skills before your (at least American publisher) debut in Thunderbolts #70 at Marvel?

Caselli: I was in high school when I realized making comics was what I wanted to do with my life. I studied for exams during the day and drew a lot during the night, just to learn how to make those incredible images I read into comics. After high school I was supposed to go to college — you know, that was the “common” path of any youngster — but I said I wanted to try to break into comic industry. My parents were pretty scared of this choice, so I made them a proposal. “If in the next three years I don’t find work with my drawings, I’ll go to college and I’ll be a doctor.” Medicine is still a big passion of mine.

So, I went to Scuola Romana Dei Fumetti — funnily enough, now I’m one of the owners and I teach there — and put all my effort into drawing. My friends still say I was the one always at home at the drawing table…but I had a dream to realize, and I was sure parties would come later. I focused on human figure and storytelling, since I was sure that telling a story properly was the highest skill to reach.

What helped me a lot was the Wizard Magazine forum. In there, a lot of wannabe artists posted their drawings to be judged by other users. I realized I could have a chance since my stuff was very appreciated (there was another good guy there, his name was Mark Brooks). Another thing I did was to show my pages to any professional I could. I listened to any kind of advice, and I never felt offended or demoralized but excited to have more to learn and to improve. I couldn’t waste time. Three years to make something isn’t that much.

You debuted back at Marvel back in 2002, with that followed by an array of Image and Devil’s Due projects. Starting at Marvel is rather atypical. Were you actively working on comics in Europe before that project? Did that lead to your work at Marvel, or did something else lead to you breaking in with American publishers?

Caselli: Before comics, I worked as storyboard artist. That was a great training to sharpen my storytelling knowledge. In the meantime, I wrote and drew some short stories for Playboy to improve my knowledge of anatomy. When I felt able to make a decent portfolio, I put together some pages and bought a ticket for Chicago Comicon. Andrew Lis 19 — I love you my man, you changed my life — noticed me, and I started making test pages until Andrew gave me the chance to work on that fill-in issue.

Honestly, I wasn’t ready to work for Marvel. Deadlines were crazy for a beginner and the pressure was too heavy. So, I started making stuff at smaller publishers to improve scheduling, speed, and quality, all at the same time. During that time, I met Tim Seeley and we’re still close friends. We shared our path and grew up together, both as men and as artists. After four years C.B. (Cebulski) called me back at Marvel and here I am.

You’ve stayed very busy at Marvel, especially after launching Avengers: The Initiative there in 2007. Launches aren’t always what you get. Sometimes you get lengthier runs on books you launch like Secret Warriors and X-Men Red. Other times you drop in on big books like Avengers and Invincible Iron Man. How does it change the job when you’re the initial artist on a book and have some more time to make your presence felt? Does it make the job easier if you’re there from the beginning, or does the job feel much the same either way?

Caselli: I definitely love to start projects from issue one. The creative team opens a restaurant, and the audiences are invited to test the food. And the nice thing is that you can choose your menu. When you jump into a big title during a run that has already started, I feel a little bit confused. I know people are used to a certain kind of “food” and you have to continue to please them. It usually takes me two or three issues to feel confident with characters and the setting. I loved working on big titles such as Invincible Iron Man, since in that case it was a sort of a new starting point, and I could really put my fingerprints on the title.

I take all of that like a challenge, and I find it fun to make the job as smooth as possible. When you start on a project you know that the book will be your best friend for a lot of hours, and you want to have those to be happy hours. But to make it happen, you have to get to know the friend properly and feel comfortable with them.

One of the things I really enjoy about your work is how your pages always maintain a real energy and sense of momentum to them. A big part of that comes from your layouts, in my opinion. Whether it’s the five panels of Cable at the top that stairstep down or the final one of him making a trademark Cable face, what’s your approach to laying out a page like this?

Caselli: First of all, I’m very happy that you noticed this subtle work behind the page!

Yes, storytelling is the most important thing to me. Once John Romita, Jr. told me, “A good artist can be acclaimed in the moment, but good storytellers remain in the business longer.” I kept that lesson in mind and I try my best to live up to it.

I usually start with a very loose sketch of the page, and I try to see how the eye of the reader is driven into the page. There are a lot of tricks to make it happen and this is the “second job” of the comic artist: draw nice figures and have the reader see what you want them to see.

When you first receive a script, like the one for this issue, what’s your process for getting to your final inks? And are you working more traditional or digital these days?

Caselli: At the beginning, I read the script carefully, really focusing on what I’m reading. I need silence and a quiet place to read since I start to imagine the sequences in my mind like a movie sequence. I keep my notebook with me, and I start sketching the pages very quickly. In this phase, I adjust what I’ve imagined and try to frame it into panels in the most efficient way.

I draw the main poses and mostly faces on paper and then I ink the page digitally. Sometimes, to find the right pose of a character, I use tons of paper, and when I feel I found what I wanted, I ink that pose.

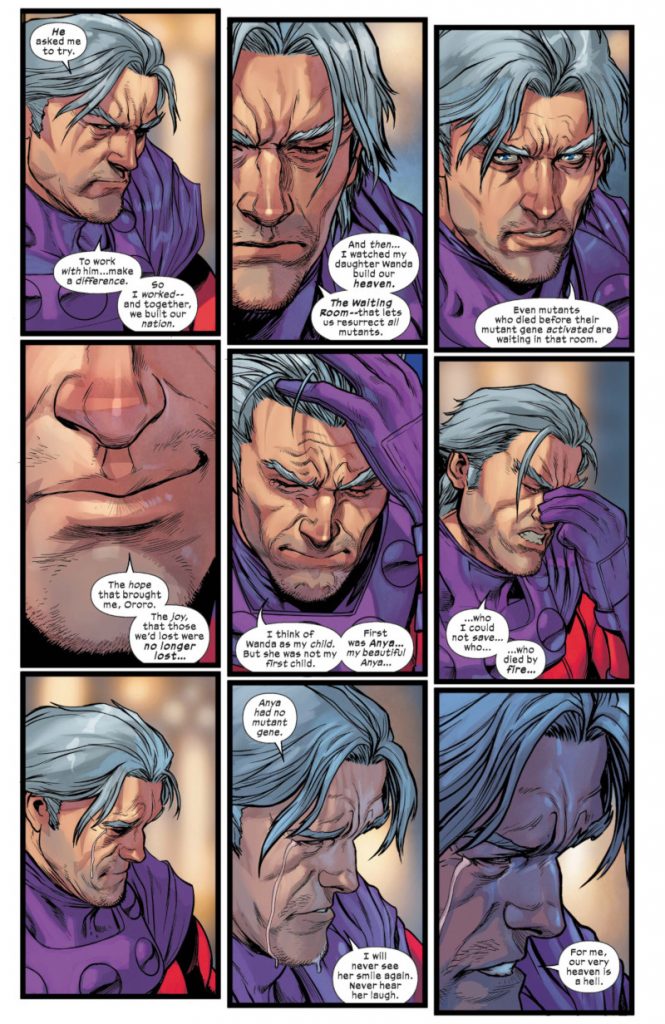

This page underlines one of your greatest strengths in my mind: your character acting. Your character work has always been exceptional, and in a nine-panel grid of just a character emoting at varying levels of zoom, you’ll need to be. How do you approach character acting, and what’s the key to bringing someone like Magneto to life without being over the top?

Caselli: Thank you again for noticing this! The acting of a character is what takes me more time than other things. Since comics don’t have sound, I have to make their voices heard through their body language. I need to know the character deeply and try to imitate them. Wolverine won’t act like Peter Parker, so I always ask myself, “How would this character react facing this situation?”

I know it may sound strange, but I try to have an emotional connection with the character I have to draw. Sometimes it happens. Sometimes it doesn’t. But I assure you that I think about this kind of stuff all the time.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

With Jonathan Hickman.↩

With Brian Michael Bendis↩

With Dan Slott.↩

Sometimes literally!↩

Or Fist of the North Star, as you might know it as.↩

A former Marvel editor.↩

With Jonathan Hickman.↩

With Brian Michael Bendis↩

With Dan Slott.↩

Sometimes literally!↩

Or Fist of the North Star, as you might know it as.↩

A former Marvel editor.↩

The X-Men line editor.↩

With Jonathan Hickman.↩

With Brian Michael Bendis↩

With Dan Slott.↩

Sometimes literally!↩

Or Fist of the North Star, as you might know it as.↩

A former Marvel editor.↩