Elseworlds 2.0: A Vote of Confidence in DC’s Black Label

Some people love superhero comics because of the tapestry Marvel and DC weave, as the connective tissue of continuity enriches reads and assures readers of the importance and potency of the objects they hold in their hands. It’s a mental checklist that tells them that everything is in its right place, that all is right in the world, and the comics are all the better for it. It’s a feeling I understand, as I am nothing if not a creature of order. 28

I understand it.

But it’s not for me.

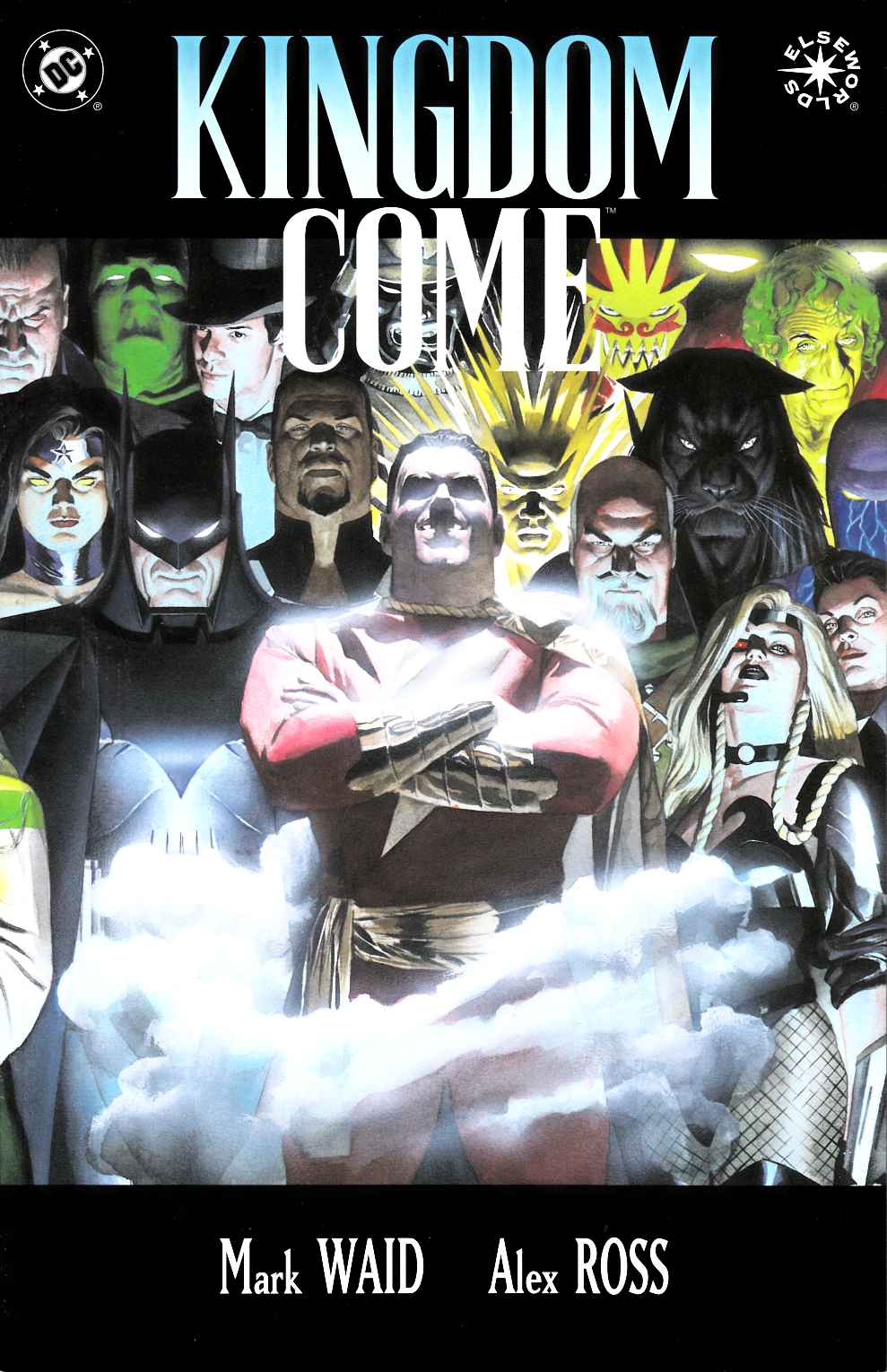

As much as I appreciate well-executed continuity plays, I’m here for a story worth telling, for art that dazzles me, for writing that thrills, and for a comic worth getting excited about. If it’s in continuity, great. If it isn’t, that works all the same. For me, continuity is a tool, not a quality defining characteristic. That’s why I long adored the Elseworlds imprint, a line DC could use for stories that didn’t quite fit what they were doing elsewhere. People like Mark Waid and Alex Ross could make audacious, inspired comics like Kingdom Come without having to worry whether or not it connected with what was going on in Justice League while still matching the essence of everything DC has ever done and ever will do. That freedom enabled creators to do what they do best – create – and thanks to that opportunity, deliver quintessential stories that may not have been possible otherwise.

Earlier this week I wrote about how mini-series were often considered lesser by some because they didn’t inherently “matter,” and it’s something stories outside of continuity can easily get burdened with as well. But the irony of that premise is when you think of the greatest superhero stories ever told – particularly those at DC – a significant portion of those titles largely exist in their own realms. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen, 29 Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, Darwyn Cooke’s DC: The New Frontier, Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale’s Batman: The Long Halloween, the aforementioned Kingdom Come, you name it. I could go on and on and on, 30 but the point is, each of those titles didn’t succeed because they matched a checklist of milestones created by the decades of writers and artists before them; they did so because they told the best stories possible with known structures and characters.

That’s also part of the reason the best superhero movies work as well as they do. What is the Marvel Cinematic Universe if not an Elseworlds-like universe of characters everyone in the world already knows? That’s what really matters in continuity: who are these people? If we can recognize Batman or Spider-Man or whomever, then that’s it. We can figure out the rest from there, even if what happens doesn’t perfectly mesh with the events of Detective Comics #272 or Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man #49. Anything more than that and you lose huge swaths of people. Entertainment shouldn’t feel like a test, and continuity can often feel like that and little more. 31

That’s why DC’s present feels so exhausting to me. When I picked up the beginning of the latest Justice League volume, I perpetually was revisiting earlier parts of the comic because I felt like I was missing something. What the heck is the Still Force? There are new Lanterns? What’s happening here? My brain was actively telling me something was wrong as I read it, so you know what I did? I stopped picking it up. That’s not the only DC title I did that with. In fact, the only main universe DC titles I’m reading right now are Wonder Twins, 32 Dial H for Hero, 33 Lois Lane, 34 and Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen, 35 a quartet of comics that are hardly defining the shape of DC’s universe. 36 And when I get a peek into what’s happening over there in the real world – *gestures wildly towards DC’s main line* – my brain immediately turns into this rather fitting James Franco gif.

In lieu of the incomprehensible, unappealing state of the main DC line, I’ve found my attention turned towards Black Label. This line isn’t a line, it’s actually an age band, making the term Black Label broad to the point it isn’t effective. That’s an idea I suggested in a feature from June, alongside another one: that Black Label as a name already wasn’t worth using because the Batman: Damned controversy tainted it. Here’s where I eat crow. While I still believe Black Label should be a line and not an age band – it’s much more effective as a line designator, not as a global age group indicator 37 – it has already stuck with me in a major way. After about a year and a half of its existence, a title being Black Label is enough for me to consider reading comics I otherwise wouldn’t. And that’s somewhere I’m surprised to be.

But I shouldn’t be.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

See: charts.↩

Or at least it used to.↩

One more name: it’s a Marvel comic, and while it is very technically in continuity, Warren Ellis and Stuart Immonen’s Nextwave must be noted as well.↩

That said, some excel at using continuity without being enslaved to it. See: Al Ewing.↩

A title that somehow exists within continuity while also creating a funhouse mirror version of continuity at the same time.↩

A title that exists within DC’s universe but also all universes simultaneously.↩

A title that might as well be a Vertigo comic outside certain characters appearing or specific beats being referenced.↩

A title that is the comic equivalent of the concept of “organized chaos.” But I love it!↩

OR ARE THEY.↩

I expanded on that idea in the article I linked to above if you’d like to know more about that take.↩

See: charts.↩

Or at least it used to.↩

One more name: it’s a Marvel comic, and while it is very technically in continuity, Warren Ellis and Stuart Immonen’s Nextwave must be noted as well.↩

That said, some excel at using continuity without being enslaved to it. See: Al Ewing.↩

A title that somehow exists within continuity while also creating a funhouse mirror version of continuity at the same time.↩

A title that exists within DC’s universe but also all universes simultaneously.↩

A title that might as well be a Vertigo comic outside certain characters appearing or specific beats being referenced.↩

A title that is the comic equivalent of the concept of “organized chaos.” But I love it!↩

OR ARE THEY.↩

I expanded on that idea in the article I linked to above if you’d like to know more about that take.↩

That’s the last time I will clarify that. Every time going forward assume that’s what I mean.↩

Some might even say Prestige PLUS.↩

And by you, I mean I.↩

This is by no means a comprehensive opinion, as I’ve only read the titles that have interested me, as you’d expect.↩

Important point: I mean this in an anyone could read it sort of way, not that it was as good as those books. It’s good but it’s not Year One.↩

That’s one place the perfect binding fails, though. There’s one two page spread in book two that sees its effectiveness neutered by the tight binding. It’s a shame.↩

That’s one other thing I’ll say about those three aforementioned titles: none of them were particularly adult, as they mostly used the freedom they were offered to tell big, wild stories – or small, personal ones, in the case of Killer Smile – rather than, you know, showing Batman’s penis.↩

See: charts.↩

Or at least it used to.↩

One more name: it’s a Marvel comic, and while it is very technically in continuity, Warren Ellis and Stuart Immonen’s Nextwave must be noted as well.↩

That said, some excel at using continuity without being enslaved to it. See: Al Ewing.↩

A title that somehow exists within continuity while also creating a funhouse mirror version of continuity at the same time.↩

A title that exists within DC’s universe but also all universes simultaneously.↩

A title that might as well be a Vertigo comic outside certain characters appearing or specific beats being referenced.↩

A title that is the comic equivalent of the concept of “organized chaos.” But I love it!↩

OR ARE THEY.↩

I expanded on that idea in the article I linked to above if you’d like to know more about that take.↩