Are Mini-Series the New Ongoings?

Was 2019 being the year of the mini-series a random blip or a sign of real change?

Despite the standard clichés and stereotypes, comic shop owners are typically rather disparate individuals. Each person and the shop they own is as distinctive as any other small business and its owner, with the differences ranging from obvious things as inventory or focuses to additional products 1 or how they want their stores to look. That’s one of the million reasons comic shops can be such wondrous, unique or downright strange places: you never know what you’re going to get. They’re all so different!

But after talking to many retailers over the years for pieces and podcasts and visiting with them at events like ComicsPRO’s annual meeting, there are a few consistencies you discover in regards to what works and what doesn’t for shops. And one uniform idea I’ve heard is a pretty important one: by and large, mini-series don’t sell. Of course, it’s not that shops don’t want them to sell. In an ideal world, every comic they order sells dozens, hundreds, thousands of copies! It’s just that in the era of the trade paperback, a mini-series is often prelude to six of the most feared words you can hear from a customer: “I’m going to wait for trade.”

That in of itself isn’t a problem, of course. Waiting for trade is a perfectly reasonable thing to do, and something many readers – including myself – do on a regular basis. But there is a considerable portion of those readers who eventually just forget that comic ever existed. And when the trade arrives, there’s no one there to greet it. And that’s a problem, and not even the only one minis face. Another of substance is a weird, tacit belief many comic readers have long shared: the idea that a mini-series is inherently not important, or at the very least, lesser. If they skip said mini-series, it won’t matter, because in regular ol’ floppy comics, we’ve created an air of insignificance to the average mini. And being important is essential to the comics consumer equation.

These ideas are all a thing. These ideas have been a thing for quite some time – certainly since I started writing about comics – and it’s enough to hamstring otherwise impactful, notable releases that have been unfortunately reduced to the relative ghetto of minidom. That is, if they ever became a thing, as this all bounced back to publishers, many of whom took those inputs – retailers don’t want to order minis because readers don’t value them – and made a decision that minis would be a minimal focus for them. After all, why would they produce something that wouldn’t sell?

And yet, in 2019, all of this was not the case. As I was putting together a recent feature on the year that was for comics retailers, an astonishing overlap between the majority of the shops began to appear: the biggest titles from the largest publishers were all mini-series. Each and every one of them was at least initially designed to be a finite length, an idea that once would have been a kiss of death. 2 But in 2019, being a mini-series was often a prelude to success, not failure, with the top titles of the form leading the way for readers, retailers and publishers alike. All of a sudden, it was cool to be a mini-series in an industry where that was almost never the case.

It’s a curious situation, and something I’ve been ruminating about quite a bit. That’s at least in part because the big question about this phenomenon isn’t whether a trend is real, which is what I normally explore. Instead, the question is an altogether more interesting one. It’s this: was the year of the mini-series a random blip in the otherwise consistent belief structure of how comics work, or are minis the new ongoings and this was a sign of real change? That – and how this came to be – are far more interesting questions altogether.

Naturally, before we can explore this trend in full, we have to look at the titles that led the way in 2019. As I said, there was a list of comics that retailers repeatedly brought up to me as successes from the year, and I’d wager none of them will really surprise you. 3 They were:

- House of X and Powers of X, two six-issue mini-series that were really one 12-issue maxi-series

- Doomsday Clock, a 12-issue maxi-series at DC that took several years to complete but finally did so in 2019

- Black Label, the adult-aimed prestige

lineage band that featured a slew of high profile, high production value minis starring DC’s most notable characters 4 - Once & Future, a BOOM! title originally announced as a six-issue mini-series 5 that eventually graduated to an ongoing

- Little Bird, a five-issue mini-series at Image that is really the first book amongst multiple that will occur in the world of the first comic

These five comics or ideas earned by far the most mentions amongst retailers this year, 6 with each driving interest and sales in a wide mix of retail stores from around the globe. Each was at least initially designed as a mini-series, and they didn’t just do well in the eight shops I spoke to, they led the way for their respective publishers overall. They were the clubhouse leaders, the leading lights, and the books that drove the conversation for the top four names in the direct market. And crucially, it wasn’t just the publishers and retailers: these titles connected with readers too.

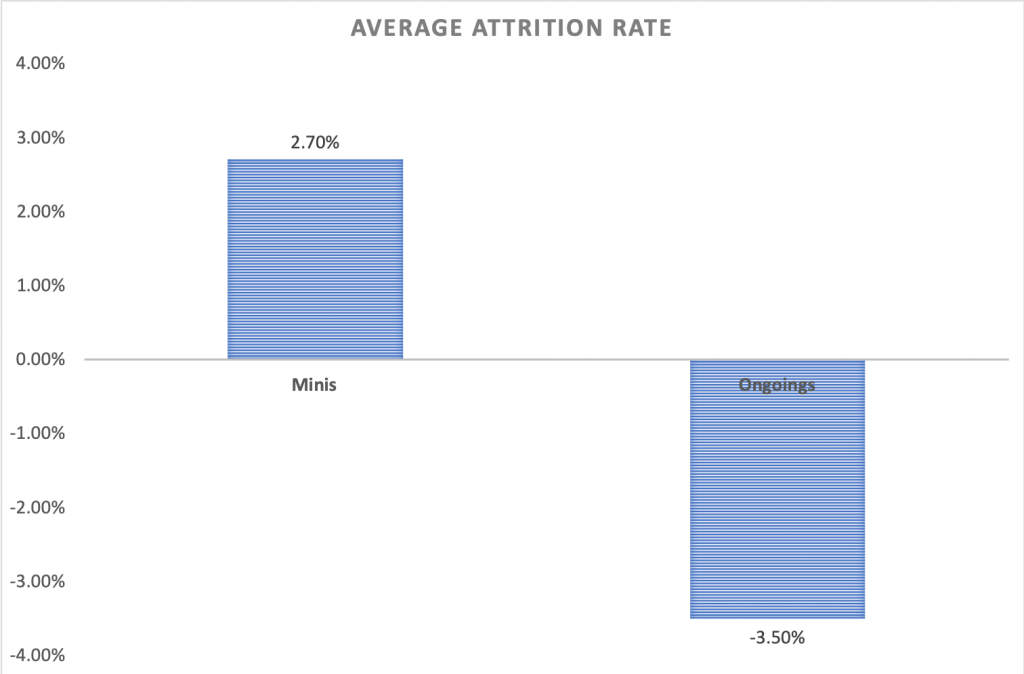

But don’t just take my word for it. Let’s look at some data. One of the surest indicators that there is real consumer interest in comic shops is attrition rate, or the rate at which orders from comic shops drop off as a series progresses. The lower the attrition rate – meaning the greater the velocity of the decrease – the less a title is seemingly connecting with readers, and vice versa. After all, post #1, the top driver for shop orders is how previous issues sold in-store. 7 If a title doesn’t sell, orders are slashed to protect shops from unsold, often unreturnable inventory.

Before the following charts are revealed, though, I wanted to note a few key things. First, what I did here was total up the orders for all of the aforementioned minis released in 2019 8 and then figured out what the average attrition rate was starting with the transition from #2 to #3. The dip from #1 to #2 wasn’t included in the mix because it’s such a brutal drop and it rarely has anything to do with reality. It’s just what happens. 9

Second, I wanted to provide some context for the attrition rate of these minis. It’s hard to know if an attrition rate is a good one without something to compare it with. To do that, I picked the top ongoings for Marvel and DC in 2019, or Immortal Hulk and Batman, respectively. I figured there was no better examples than the biggest hits each publisher has in the ongoing realm, especially considering Batman is literally the benchmark for Diamond Comic Distributors’ order metrics. I should mention though that once I figured out those numbers for the ongoings, I cut any anomalous rises or falls in orders, as those were universally related to some level of gamesmanship by their respective publisher. 10 Those outliers make the numbers wonky and inaccurate, so outliers are cut.

And now, the charts!

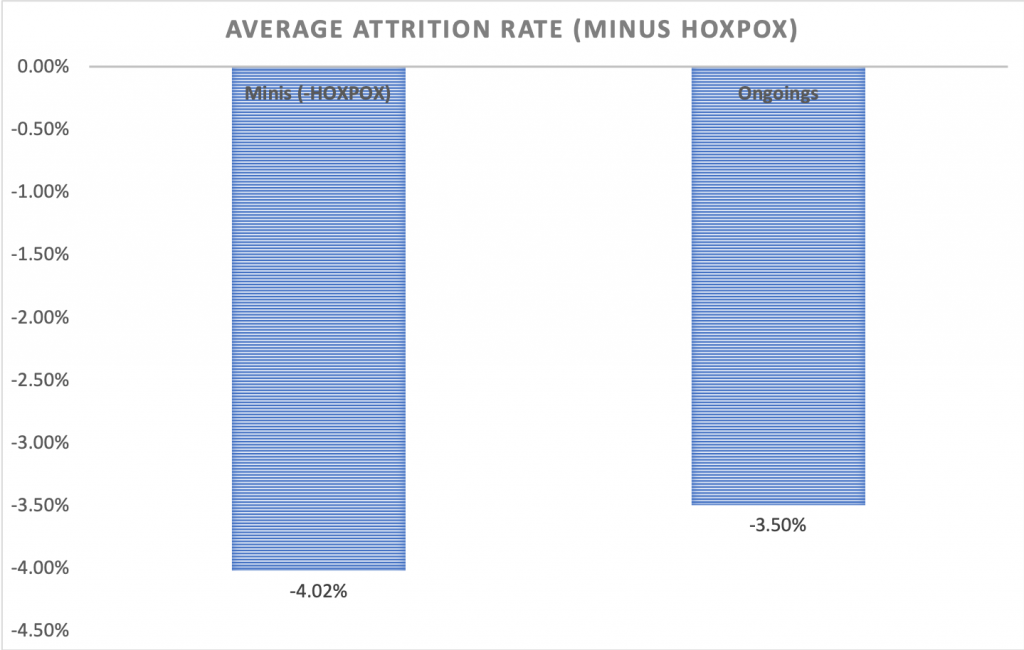

Huh. So when I averaged out the attrition rate for minis from issue #2 onwards, it turned out there wasn’t attrition at all. There was…the opposite of attrition. Whatever that is. There’s no good antonym for attrition, so I’m just going to simplify it: on average, orders went up. That means for the minis at least, reader interest in them went up as the titles went along. And that is super weird! It’s strange to the point where I need to redo this chart because, like with the ongoings, there is an outlier here. House of X and Powers of X were so outrageously popular that they single-handedly 11 swing the attrition rate to the positive side. They’re anomalous to the point they break this exercise. Let’s look at this chart again without those two titles.

Okay, that makes more sense. Once you remove the biggest guns, the orders of those top minis drop off at a roughly comparable rate of the ongoings I looked at, albeit a little faster than those titles did. But that’s a wild thing to think about! That means these minis – which, yes, includes a Watchmen/Superman maxi-series 12 and several Batman-adjacent titles 13 but also a BOOM! title about Arthurian legends and a very political dystopian story at Image by relatively unknown creators – dropped off, on average, at about the same rate per issue as the most popular ongoings at the Big Two. That is fairly unheard of, even if there’s a lot of noise when you’re looking at issue #3 to #4 drop offs versus #27 to #28 or later.

This is unusual. It was a real thing that happened! But very unusual, nonetheless.

Here’s another question for you: was that performance an outlier because of material or was it a portend for the future? It’s easier to say mini-series are successful when it’s a relaunch of the X-Men from Jonathan Hickman or prestige Batman comics we’re talking about. Of course they are! That’s to be expected.

But as much as the material certainly played a major part, it’s a little of column A and a little of column B. And the reason I believe it’s a glimpse of the way things might work going forward is because of where we’re coming from. The growth in impact of the mini-series, in my mind, is directly related to years of tomfoolery by the publishers at the top of the direct market. When DC relaunched its line in 2011 with the New 52, it kicked off a wave of actions by the Big Two that effectively neutered the ongoing. Between the pair, Marvel and DC relaunched 14 10 times in the 2010s, depending on how you count. 15 Before then, that was largely a foreign concept outside of the post-Crisis on Infinite Earths rejiggering DC went through, and even then, that was relatively minor compared to what we saw in the past decade.

Now, they’re just something that happens, an expected part of the mix for Marvel and DC readers. And as mentioned many times before, both here and elsewhere, these relaunches give readers something never deliberately offered by the Big Two before: a jumping off point. It snapped long-standing strings of big numbers on covers, and for the average superhero comic fan who long wanted to ensure they had every issue of a series they’ve been collecting for forever, this broke the chain. The completionist brain was shattered, and readers had to reorient around a new north star. What that is varies and depends on the reader, really, 16 but ultimately, comic fans no longer have a reason to stick around beyond their own love of the stories. 17

These relaunches devalued longevity, and as ongoings became mostly ongoings in name only, 18 the difference between minis and ongoings evaporated. There’s almost no distance between those ideas anymore outside of a few exceptions. 19 And if you’re a publisher or a retailer or reader even, whatever offers you the most #1s – the easiest issue to sell, as they’re theoretical jumping on points – seems like the best play. Combine that with how ordering works – which, again, peaks with #1 before standard attrition comes in – and you can see the appeal of this direction. Diminishing returns hurt less when you are on high and the next new volume is seemingly always on the horizon.

That’s a big part of the reason I believe 2019’s flurry of successful minis could be the beginning of something more. The potential ceiling and, crucially, floor are higher for retailers when it comes to mini-series. Even creators have started to turn towards finite series, seemingly. In a recent appearance on Off Panel, writer Matthew Rosenberg spoke of how a newer class of creators at Marvel have found a home and, perhaps more importantly, success with minis. He’s not the only one I’ve heard this sentiment from.

And you know what? I get it. We’ve seen the biggest ongoings at the biggest publishers and creators struggle under the weight of history after a while. I’ve heard from multiple retailers that even major titles become nearly impossible to onboard new readers to after 20, 50, 80 issues. 20 “I’ll wait for the next relaunch,” an inversion of the previous idea about trades, is something one might hear when discussing a long-running ongoing. Beyond that, readers are sampling more than ever, making value judgments off one issue on whether or not they even want to proceed on to number two. Patience is rarely a virtue for comic fans, and knowing that you’re only committing to five issues rather than 50 or 100 can make a huge difference to your average consumer. 21

That’s why, again, 2019’s flare-up of successful minis feels like it was both triggered by the high-end material in the market and because it’s part of a larger trend. It’s an indicator for the future, and one that’s reflective of where we’re coming from and of the shifting desires of comic shop customers, as carried on down the chain. It’s the actions of the Big Two mutating what consumers look for in their comics, and the perfect storm required to break a long-standing belief in comics retail that minis are almost universally lesser releases and that ongoings are the end all, be all.

If there’s one important takeaway from this piece, it should definitely be this: if you want to sell a lot of comics and you’re a Big Two publisher, hire Jonathan Hickman.

Okay, that won’t work for everyone. But if there’s a second important takeaway, it’s this: just because things have always worked one way doesn’t mean that should always be the only answer. Unfortunately, the days of your Bone’s and The Walking Dead’s – where you keep publishing an ongoing until you find your audience – might be over. Just making an ongoing and call it a day isn’t the right play for the majority of titles and creators in the direct market anymore, even if it was for a long time. Ongoings can be a long, hard road to diminishing returns, with the exception mostly being creator-owned titles that hit it big in collected formats, 22 as the gains from varying collected forms become the true focus and the single issues become almost trailers for the trades.

Perhaps an even more important takeaway from all of this is that even if minis aren’t the new ongoings, trying something new – or at least different! – is perhaps more valuable than just rolling out the same old playbook as before. That’s maybe the most interesting part about the five titles that led the way in 2019. It wasn’t just that they were finite series that made them stand out. Each of them had something that made them a little different than their peers. And that matters, because jamming every idea into the same structure over and over isn’t necessarily the right play if it isn’t working. It’s comic book insanity, as we see publishers doing the same thing over and over again, expecting different results each time. Each project needs its own distinct angle, its reason for being, its differentiator. That can lead to gains both creatively and commercially, even if a title is an ongoing.

That’s why something like Jonathan Hickman and Leinil Yu’s current X-Men title is such an interesting comic. Obviously it sells well at least in part because, well, it’s the X-Men, and it’s the flagship title in the line House of X and Powers of X spawned. But its one-and-done structure, in which each issue is a standalone comic that fits into a larger whole, is quite different than we normally expect from an otherwise deeply serialized medium. It’s an ongoing that doubles as a series of one-shots, making every single issue a jumping on and jumping off point. Is that risky? Sure. But it’s also exciting, fascinating and engaging, and more importantly, it seems to be working within the ongoing structure. It’s manipulating the format to work in its favor.

Another fascinating approach is BOOM!’s long-standing love of stealth ongoings – or minis that could flex to ongoings if the audience is there – which are the comic equivalent of having your cake and eating it too. If Once & Future didn’t pan out, it’d be done at six issues and that would be that. But if it hit, it could stretch outwards, allowing for both short and long-term potential. BOOM! does this on the regular, and it’s an intriguing ploy for two main reasons. First, the repetitive usage of this incentivizes readers to get onboard early with BOOM! titles so you can get more of them if you like them. Second, it limits risk, ensuring less burn if it doesn’t work out. It’s an improved ceiling and limited floor in one package, a flexible package designed to be a purely upside play.

All of this is why I’ve long believed the Hellboy model is something worth taking a longer look at. Making your comic an ongoing comprised of connected mini-series feels like the best of both worlds, as it gives more readers a chance to jump on without losing the completionist angle. 23 What is it if not the much bandied about “season model” rolled out in front of our very eyes? The counterpoint is it never turned Hellboy into a gigantic hit in single issue form. But look at what it did become: a 25+ year run of comics with singles that sell decently well and a cornucopia of collections ranging from trades to gigantic omnibi. Its versatility is its greatest strength.

Of course, going with a different model doesn’t always work either. As appealing as I find the idea to be, I’m not sure the oversized quarterly is something that truly works in the direct market. An infrequently released ongoing can be a backbreaker in this market. 24 Surprise launches logistically don’t seem to work. As intriguing as I might find it, the $9.99 supersized one-shot might only be worth rolling out situationally.

But as we saw in 2019, it can pay to be something different if it fits what you’re trying to do. And the good news is, we’re seeing an increase in flexibility across the board, as publishers are really going into the lab recently and experimenting with what they do. Marvel’s almost drowning people in an array of minis, one-shots, reprints and assorted other non-ongoing structures. 25 DC’s rumored 5G reboot has been suggested to come paired with a Black Label focus for the more well-known iterations of characters, an intriguing restructuring towards the strength of their line. DC and Image have been rolling out more maxi-series 26 than we’ve seen in years, with Tom King and Mitch Gerads particularly excelling in that form. BOOM! has its aforementioned stealth minis. Vault’s line is heavily built around minis, perhaps almost primarily so. These all push back against traditional thinking of how to sell single issue comics in the direct market. And yet, they’re seemingly working, even if no answer is universal for comic shops.

To close, let’s go back to the original question. Was 2019 a random glitch in how comics work, or was the rise of mini-series a sign of real change? While it was undoubtedly affected by the material, I tend to think it’s more the latter, even if it isn’t mini-series themselves destined to become the new ongoings. It’s almost certainly not as clean as that. But if this past year did anything, I hope it dispelled with the belief that there’s a one size fits all answer to what sells in comics. A comic can be anything and succeed in the market today. A mini-series. A one-shot. Graphic novels. Collections of webcomics. Heck, even ongoings. Maybe especially ongoings, if they do something new with it! But the era of the traditional ongoing series as the monolithic structure of comics feels like it’s on its way out, effectively buried by the actions of the pair of publishers that once propped it up.

Including games or toys, but also things like connected coffee shops or selling food.↩

Outside of events, of course.↩

Because they were successes, after all.↩

But mostly Batman-related characters.↩

And even labeled as one until the end of its first arc.↩

At least amongst single issue titles.↩

Unless #2 or #3 or #4 sees its orders become final before the release of #1. In that case, the number one driver for shop orders is a combination of educated guesswork and prayer.↩

For Black Label, I only incorporated the titles that were clearly Black Label specific books, as if it was a line and not an age band or whatever. That means no Sandman Universe or Hill House titles are factored in here.↩

This is because #1s are normally so laden with variants and order gates and things of that sort that the orders for a #1 are basically a piece of fiction. Once #2’s orders are revealed, it’s more reflective of reality.↩

i.e. Cardstock covers for Batman, for example.↩

Double-handedly?↩

Albeit a crazy delayed one.↩

All of which were $4.99 to $5.99, which is worth mentioning.↩

Or renumbered, or rebooted, or rewhatevered.↩

That means New 52, DC You, and Rebirth on the DC side and Marvel Now, All-New All-Different, All-New Marvel Now, Marvel Now 2.0, Marvel Legacy, Fresh Start for Marvel, but doesn’t include Avengers Now and the Heroic Age. So it could be 12.↩

I just read comics I like, which I imagine is the main driver for people, but maybe not?↩

Which I would argue is a healthier mindset anyways!↩

Two great examples of how this manifests: The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl had two #1 issues in one year, while Guardians of the Galaxy recently had two #1s in 364 days.↩

Many of which, bizarrely, are now in creator-owned comics.↩

Case in point: from what I’ve heard, Wonder Woman #750 struggled to move for shops, and that was all-star creators working on a monster milestone of a comic.↩

I’ve made these same decisions.↩

Or Batman, because Batman is the exception to all comic rules.↩

This is exactly what Little Bird seems to be doing.↩

In fact, it might be too much, guys.↩

Finite series that run 12 issues or longer.↩