Revisitor: Batman Wins, But Also Loses, in the JLA classic, Tower of Babel

Revisitor is a regular column in which I look back on personal favorites from comic history, whether they’re a single issue, graphic novel, comic strip, webcomic or basically any form of sequential art you can think of. When I do this, my hope is to include perspective from some of the people who worked on these comics. That may not always happen. The good news is, it did this time.

If you’ve been reading them long enough, it can feel like you know everything there is to know about superheroes. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing. There’s comfort to the concept, a happy knowledge that in the long arc of storytelling, these characters are good and always win.

That might especially be the case for Batman. When I was growing up, it seemed as if there was nothing that could stop him. I first started reading his stories with Knightfall, and no matter what he faced — a broken back, a usurper powered by pure 1990s comic book energy, a city destroyed by earthquake, a pandemic, etc. — the Dark Knight would solve the problem. During that stretch, he was both the unstoppable force and immovable object, acting as the answer to every “Who would win in a fight?” question. This wasn’t because of his impossible powers or overwhelming physicality. It was simply because he’s Batman.

That worked for the character for a time, but infallibility can have diminishing returns. That’s because superhero comics tend to be best when they find ways to genuinely surprise us. Comfort is good, but the thrill of the new? Of growth? Of the unexpected? That’s where magic often happens.

Superhero comics don’t always just surprise readers, though. Sometimes they surprise the creators themselves.

Mark Waid’s earliest days on 1997’s JLA title 15 certainly fit that bill. The writer was in the midst of a sabbatical from his work on The Flash at that point, as writers Grant Morrison and Mark Millar had taken that title over so they could dig into a story they cooked up for it. It also allowed Waid to reduce his writing schedule a bit, something he was excited for. It was a good idea in theory, but one that didn’t work out as anyone expected.

“All that happened was that poor Grant ended up overworked, so I had to step in to help with JLA, and neither of us achieved our goals of a more peaceful and tranquil year,” Waid told me.

It was a transition aided by familiarity. Unexpectedly writing two early arcs of JLA was made easier by the fact that he and Morrison worked closely together in those days, often discussing and building off each other’s ideas. The pair had “similar sensibilities when it comes to DC stuff.” That led to Waid’s fill-ins feeling congruous with Morrison’s efforts, helping continue the feel of the volume overall. This also made Waid a fitting choice to take the title over when Morrison completed their run on JLA.

And when that happened, Waid cooked up an all-time surprise for readers, one that helped redefine Batman as a character in some ways and helped us better understand that while the character may always win out against his foes and circumstances, sometimes even the Caped Crusader can be his own worst enemy.

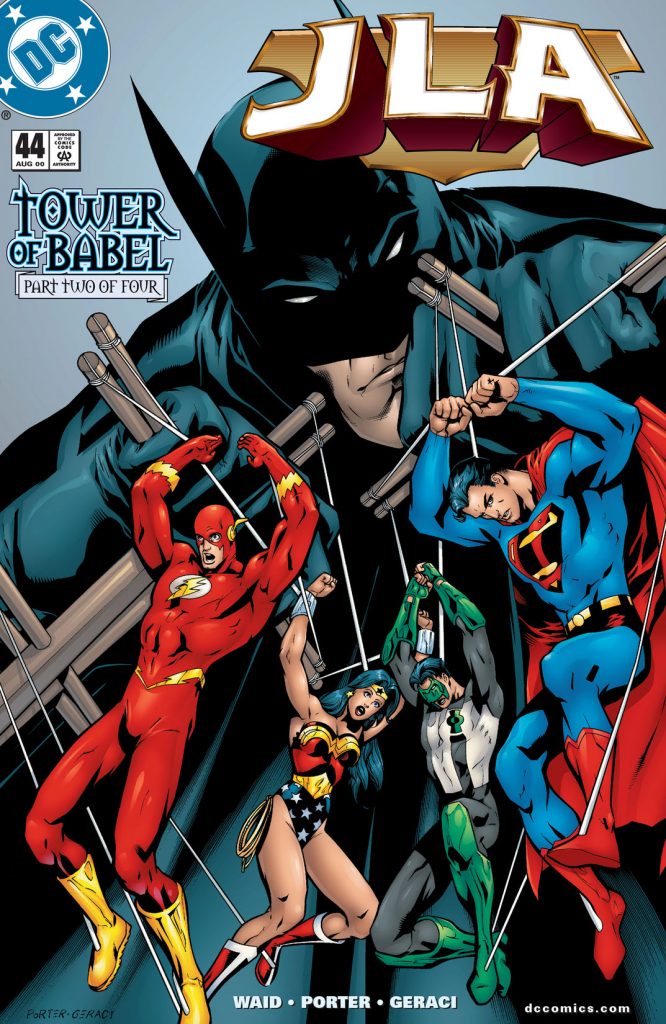

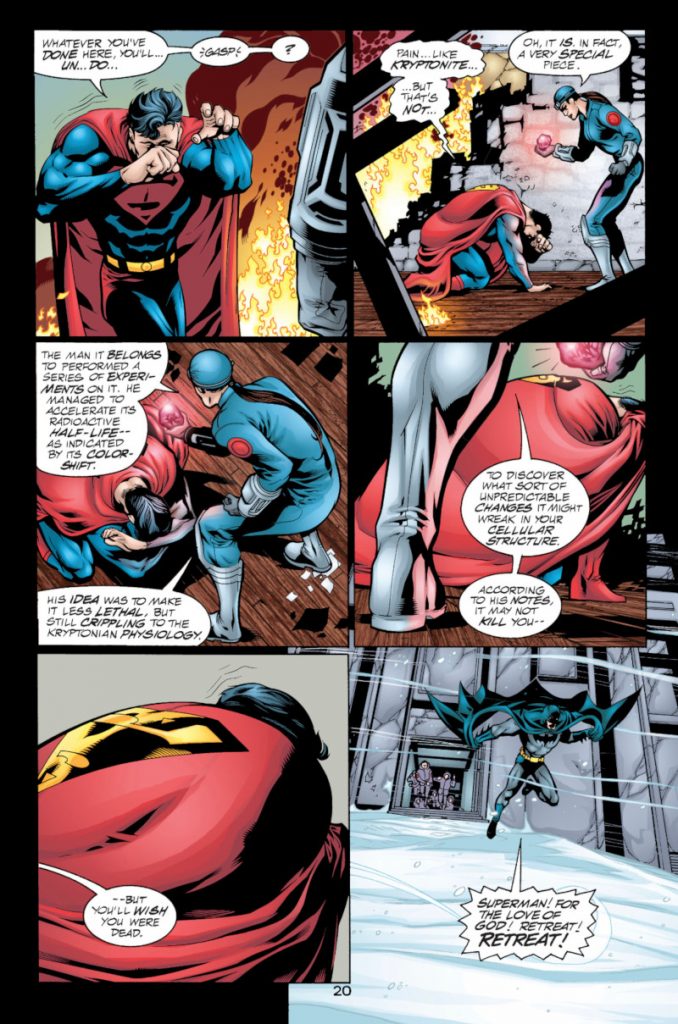

This was Tower of Babel, a storyline from Waid and artist Howard Porter 16 that took place in JLA #43 to #46, a four-parter that found Ra’s Al Ghul tearing the JLA apart by using Batman’s own contingency plans for the Justice League against them. It’s an incendiary read, one in which the League’s strategic leader is ousted not because he brewed up plans to defeat his teammates; it was because he didn’t tell them those schemes existed to begin with.

This storyline absolutely floored me at the time. Everything in it was massive and shocking. Bruce Wayne’s parents’ coffins were stolen to distract Batman! Every Justice League member is soundly and easily defeated! Ra’s Al Ghul really seems like he’s going to win, both because of the execution of those plans and because he’s broken humanity’s ability to understand language! 17 It’s all Batman’s fault, because he doesn’t trust anyone but himself! And he’s voted off the team in the end, resulting in a Justice League with no Batman! It went places I never could have expected as a reader.

Tower of Babel was immediately one of my favorite comics when I first read it, and I’ve reread it many times since. And while much of its initial power comes from the reader’s realization of what’s happening — which occurs in parallel to Batman’s own discoveries about the situation — its lasting impact stems from what it means about the character, the cost of his secrecy, and its exploration of the true power of being a Justice League member. Much of the tension of Waid’s run is built from the events of this story, as they don’t truly culminate until JLA #50, with Tower of Babel being the kindling to the flame of his larger arc.

That’s why I had visions of grand plans in my head when I reached out to Waid to talk about this story. Surely the writer was not unlike Batman in his thinking, always two steps ahead of readers and the characters on the page. Nope! That’s not how Waid rolls. More than that, the core concept of Tower of Babel wasn’t even developed as an idea for the Justice League; it was one the writer had for an entirely different project, which he repurposed in a time of need.

subscribers only.

Learn more about what you get with a subscription

These were issues 18 to 21 and 32 to 33.↩

As well as inker Drew Geraci, guest artists Steve Scott and Mark Propst, layout artist Zander Cannon, colorists Pat Garrahy and John Kalisz, and letterer Ken Lopez.↩

And he sort of does win, for a time, in how the League struggles in the wake of the story.↩

These were issues 18 to 21 and 32 to 33.↩

As well as inker Drew Geraci, guest artists Steve Scott and Mark Propst, layout artist Zander Cannon, colorists Pat Garrahy and John Kalisz, and letterer Ken Lopez.↩

And he sort of does win, for a time, in how the League struggles in the wake of the story.↩

If the Xavier Protocols sounds familiar, it’s because that idea was used on that line after Waid departed.↩

Shouts to the excellent Prometheus arc in JLA #16 and #17!↩

He figures out how the vote will play out before the League does, because that’s how Batman rolls.↩

The Bryan Hitch art really helps it pop.↩

And then Batman shows up separately from Bruce Wayne, which is a real mind-bender that leads to a whole new arc.↩

Porter and inker Drew Geraci only solo around half of it, with Zander Cannon stepping in on layouts for part of issue #45 and guest artist Steve Scott and guest inker Mark Propst finishing it off with #46. If it was Porter and Geraci throughout, it likely would have been even more effective.↩

Waid censored his cursing, not me!↩

As the final chapter of Waid’s larger story, issue #58, emphasizes at the end. Waid writes one more issue with #60, but it’s standalone rather than part of his overall tale.↩

These were issues 18 to 21 and 32 to 33.↩

As well as inker Drew Geraci, guest artists Steve Scott and Mark Propst, layout artist Zander Cannon, colorists Pat Garrahy and John Kalisz, and letterer Ken Lopez.↩

And he sort of does win, for a time, in how the League struggles in the wake of the story.↩