Brian K. Vaughan Talks Characters, Collaborators and We Stand on Guard

While I’m not one to play favorites most of the time, I’d be lying if I didn’t say Brian K. Vaughan is one of my favorite writers in comics. I’ve written about his work a lot so you may have already guessed that, but still, dude’s great. He’s written a lot of my favorite comics. Y the Last Man was the comic responsible for my return to reading them. Ex Machina and Runaways are two other era favorites. Saga’s a modern classic. The Private Eye might be one of my favorite things of the past few years. In short, he’s the bee’s knees.

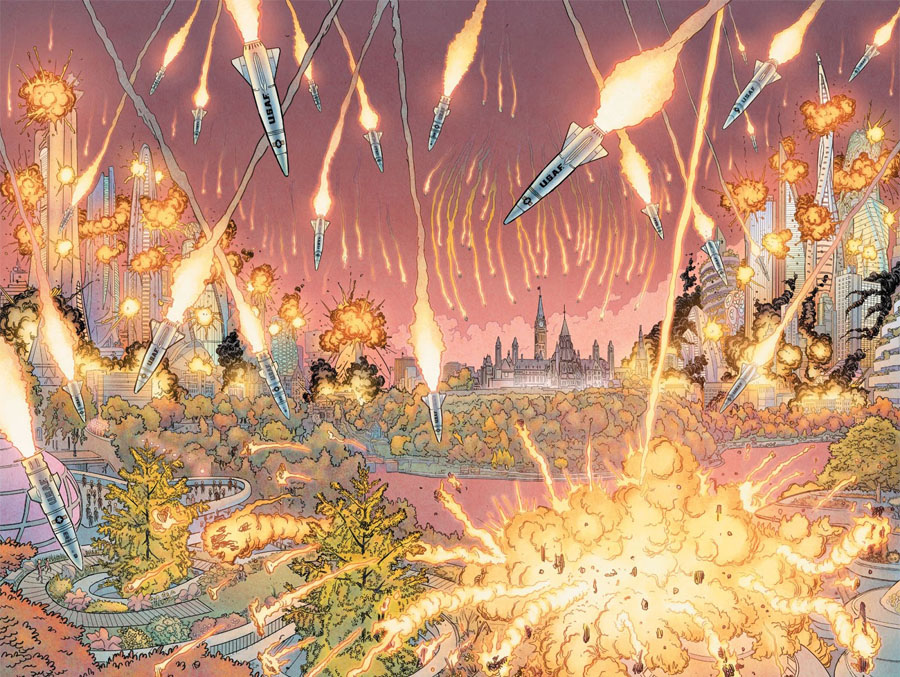

One of his recent works was We Stand on Guard, an Image Comics title he put together with artist Steve Skroce, and it digs into a world where the United States and Canada are at war, and a small band of Canadian freedom fighters worked tirelessly to push their aggressive neighbors out of their home. This is going to shock you, but I dug that comic, both for Skroce’s work (which I talked with the artist about last week) and for Vaughan’s (not to mention their other collaborators efforts). And today, I continue the discussion of how that book came together with Vaughan as we talk his return to comics, what interested him about the story of We Stand on Guard, working with Skroce, the fate of my home, and more. Give it a read, and if you haven’t read it yet, the hardcover of We Stand on Guard is out now in local comic book shops everywhere.

Just around six years ago I wrote a piece about you and how your comic future was uncertain past the close of Ex Machina. Now, you’re everywhere! You’re actively working on Saga, Paper Girls and Barrier, We Stand on Guard’s about to come out as a hardcover, and you even teamed up with your Panel Syndicate partner Marcos Martin to tell your own in-continuity Walking Dead story. As comic readers, we’re lucky for it. But for you, what makes the comic book medium so irresistible?

BKV: Thanks, David. I love collaborating with artists, I love serialized storytelling, and I love owning and controlling what I help to create. It’s comics or bust.

I always say the magic in comics comes from the marriage of words and art into something greater than the sum of their parts. And with your books, you work with a laundry list of incredible partners, including but not limited to Fiona Staples, Cliff Chiang, Matt Wilson, Jared K. Fletcher, Fonografiks, Marcos Martin, Muntsa Vicente and your We Stand on Guard partner-in-crime Steve Skroce. That’s the ’27 Yankees of comic artists if I’ve ever seen it. Not only that, but you seem like an encouraging, supportive collaborator. To you, how important is it for comic creators to not just find partners of this caliber to work with, but to make them equal collaborators who are unleashed to tell the story to the best of their abilities?

BKV: I’m incredibly lucky. I love all of those geniuses, except for Marcos. How important is it to make artists equal collaborators? If I didn’t, why would they work with me? It took me a long time to accept this, but comics is not a writers’ medium. I need them much more than they need me.

While there are plenty of reasons your work stands out, to me, your ability to create unique, real feeling characters has always been what stood out the most. Whether you’re working with leads like Saga’s Alana or Marko or smaller parts of an ensemble like We Stand on Guard’s LePage, what do you think the key is to achieving verisimilitude in your characters without feeling like “BKV players” so to speak?

I try to base characters on people I actually know, and I try to get to know a lot of weird new people.

We Stand on Guard in some ways felt like a different kind of book from you. It was definitely more focused on a central conflict, what with the whole USA vs. Canada story driving the narrative. What inspired you to tackle a story like this? And beyond that, what interested you about the US’s relationship with our neighbors up north?

BKV: Well, most of my closest collaborators are from Canada, including my wife. When she became an American citizen, she literally had to swear an oath saying that she would take up arms against her home country if need be. I thought that was a hilarious prospect, until I started researching an old American initiative called War Plan Red, and the possibility of eventual armed conflict with our neighbors to the north suddenly started to feel a lot less far-fetched.

But really, We Stand On Guard isn’t about Canada any more than Pride of Baghdad was about lions. I wanted to challenge myself to try to better understand, and maybe even sympathize with, “the enemy,” whoever that might be in our country’s history.

Speaking of up north, I just have to ask as an Alaskan: where do we stand in this whole mess? My people need to know!

BKV: Never fear, in 2124, you folks are all just fine…as long as you don’t mind hosting countless new military bases or giant fucking robots stomping across your backyards every day.

We already talked about working with artists a bit, but what made Steve such a perfect fit for this book? And did the fact he was from Canada make him an even more appealing potential partner for this project?

BKV: Have you seen his pages? There’s a reason Steve is one of the most in-demand storyboard artists in Hollywood. He draws some of the best, most absurdly detailed action scenes in the business, but he’s equally gifted at quiet, character-driven drama. I’ve been obsessed with his work since those Alan Moore Youngblood issues, and helping to lure him back to comics is one of my proudest achievements.

Sorry I can’t reveal more just yet, but I’m so, so excited for what he’s working on next.

The book is filled with exceptional characters and fantastic dialogue, but let’s face it: there’s a part of every reader that loves it most for gigantic mechs. I talked with Steve about this, and he mentioned you had one particularly great note about these beasts, but I’m curious, what made them a fit for the future you were creating with Steve? Besides the fact Steve would be amazing at bringing them to life, of course.

BKV: I guess we were just looking to make asymmetrical warfare more visually compelling than an aerial drone obliterating some remote shack. And I’d been reading about how contemporary military “situation rooms” were greatly shaped by their Hollywood representations over the years, so Steve and I tried to imagine how future defense contractors might have been similarly influenced by another hundred years of American movies about giant, ass-kicking robots.

I was thinking about your work, and family seems like an essential element to almost every one of your works, whether that means your actual family or the ones you make. We Stand on Guard is no different, whether you’re talking Tommy and Amber or Amber’s relationship with the Two Four. Obviously that idea is an important one to most people, but is that a part of the story of our lives that interests you in particular, or is it something that comes up because simply because it’s so essential?

BKV: Family seems like such a broad subject that it’s almost impossible NOT to write about it. But you’re right, I’ve always been interested in families, especially the ones we choose to form after leaving, or losing, our original ones. Tribes are scary and fascinating, especially now that I have kids.

You talked about how this project was, in part, you attempting to better understand “the enemy,” and one thing that I thought was especially interesting about that is when you consider a lot of the ambiguities in the story, and one stunning parallel between the book’s protagonist and antagonist. The idea of “the enemy” seems clear, but it becomes apparent by the end that no one really knows anything besides they’re fighting and that’s just kind of what they do (even if readers are definitely rooting for one side). Is that part of what intrigued you about this project? The idea that “good” and “bad” can be a matter of perspective, almost?

BKV: Well, I struggle with concepts like “evil,” but I’m not such a moral relativist that I’d say nothing is empirically bad. For example, genocide is pretty crummy. As a reader and a writer, I just like fiction that puts me in the shoes of very different characters, especially ones with “nontraditional” values. Steve and I had no idea if an audience would still care about our protagonist after she brutally executes an unarmed American prisoner of war in the first issue, but as storytellers, it was an intriguing challenge.

Be honest: how much guff did you get for LePage’s dialogue? Or did your efforts in writing a French speaking character despite not speaking French yourself work out?

BKV: I took very little guff thanks to our Québécois translator, Mathieu Chalifoux, and to Steve Skroce, whose performances are so expressive that you could usually tell exactly what LePage was saying even if you don’t speak a lick of French. There were some occasions when I deviated from Mathieu’s translations because I wanted even monolinguals like me to understand some aspect of the dialogue, but I blame any perceived “mistakes” on the natural evolution of language over the next one hundred years, so please stop complaining and give me my No-Prize.

I don’t want to give anything away about the book, but despite the book ending with some major cast changes, a lot of the pieces are still on the table. Is this world one you could ever see yourself visiting again, or do you feel you’ve said everything you wanted to with this story?

BKV: Nah, I think Steve and I said precisely what we wanted to say about Amber with this self-contained story.

But despite the aforementioned scenes of our protagonists killing American troops, there’s been a shocking amount of interest from Hollywood in adapting this story into another medium, so I think there’s an excellent chance that the world hasn’t seen the last of the Two-Four.

For now, I’m just excited about what’s next in the world of creator-owned comics from Steve Skroce. 2016 is going to be a great year, especially if the Cavs can finish making quick work of the Raptors (sorry, Toronto).