“I Can’t Wait for People to See What We’re Doing”: Courtney Menard on the Production and Design of the New Tiny Onion

Big news dropped last week, as perpetual newsmaker and superstar writer James Tynion IV revealed the next phase of his Tiny Onion empire. It isn’t just a newsletter anymore, but a production house designed to help creators with “the development, packaging, marketing and cross-platform promotion of new creator-owned work,” per the announcement of this new enterprise over at Forbes. What does that mean, exactly? In short, it’s Tynion setting up infrastructure to help other creators execute their visions as well as possible — both in comics and beyond.

He’ll have help in doing that, as the Tiny Onion team extends beyond Tynion. It features an incredible collection of talent, including Director of Editorial Eric Harburn (formerly Tynion’s editor at BOOM! Studios on Something is Killing the Children, as well as a whole lot more), Director of Communications Jazzlyn Stone, and Director of Production Courtney Menard. This squad will bring a whole lot to the equation, but as Tiny Onion gets the word out about what this new company — which is not a publisher! it’s instead designed to help creators package their projects for publishers! — entails, the team is getting out into the public and sharing the good word about what it’s all about.

That’s what we’ll be doing today, as we’ll be exploring the world of Tiny Onion from Menard’s perspective. Menard’s a veteran of the comics space, having studied at the School of Visual Arts, worked at Z2 Comics in production, and shown her gifts in books like What’s the Furthest Place from Here? and The Deviant. As Tiny Onion’s Director of Production, she’ll be the person whose job it will be to ensure that all associated projects look and feel as good and fitting to the story as possible, an essential part of the comic making process. To dig into what that means, I hopped on Zoom recently to talk with Menard about her role, the importance of Tiny Onion, what she’ll be working on, what will be guiding her work, her love of paper, and a whole lot more. It was a fun and insightful conversation, one that might help you better understand what Tiny Onion 2.0 is all about.

You can read that conversation below, with it being edited slightly for length and clarity. It’s also open to non-subscribers, so if you enjoy this interview, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more like this, and to support the work I do here.

Let’s start with the basics, Courtney. While Tiny Onion is an old name, this is a new version of it. What is Tiny Onion, and what made it a good fit for you?

Courtney Menard: The quick answer is Tiny Onion is a production house! It’s an ecosystem of support for comics creators, a full-service editorial, production, and marketing team. We’re here to handle all the behind-the-scenes stuff that a lot of comics creators either don’t have the bandwidth for or don’t have access to so that they can focus on the art of storytelling.

The creative support aspect of Tiny Onion was especially appealing to me. I want the packaging and design of a comic to reflect the quality of the art and writing inside. Bluntly, I am also just a fan of James’ storytelling and curatorial eye and was excited to be brought on to help elevate the work within Tiny Onion’s rolodex, and to seek out new talent.

I have an idea of what a Director of Production is, but I feel like any assumptions I’d make about that would be a very incomplete view of what your job is. What’s your role at Tiny Onion, and how are you going to guide its wider portfolio of projects?

Menard: Production is the nuts and bolts building of the book – creating bookmaps, laying out pages, color correcting, collaborating with printers to add all the fun stuff like gloss, gold foil, embossing, etc. It’s taking the creators’ vision for what they want the final product to look like and figuring out how to make that real. It can be challenging, and that is why I love it. It’s like figuring out a puzzle. It’s been fun to scheme with the Tiny Onion team on how to push boundaries with printing and design, but with intention to each specific project. Whatever bells and whistles we add to our projects I want to feel in line with the world built within the story. I am a big ol’ paper and book binding nerd, and I want fans to pick up one of our books, feel the weight of it, and have their love and curiosity of physical media reinvigorated.

I know you’re just one part of the team, but you know comic creators and you know what the industry is like. Why do you think Tiny Onion is necessary?

Menard: I kind of mentioned this in my first answer about what we are, and what we are is a support system for creators. We’re the backend people who help put the books together. We provide feedback to creative vision and ultimately elevate the work. Because to me, the artwork is the most important element. And I want to make sure that the packaging of the book, the way the reader receives it, the way the creator interacts with it, is just as taken care of as the artwork was when it was made.

And a lot of creators don’t have the bandwidth to take on all that extra stuff, because making comics is hard. Having done it myself, having watched people do it, having been around it, it’s a hyper-focused thing. And so, for me, I want the artists and the writers to be able to focus on their work, and then have me and Eric and Jazzlyn and James as a support system to take care of all the other stuff. And I know that that kind of exists. It exists within publishers. But we wanted to take a totally holistic approach to it, and make sure that we were able to support each artist and creator specifically and really give it that white glove touch.

One thing that’s interesting about this is, a lot of times when creators go to certain publishers for certain deals, the reason they do so is because they can get support in marketing and in editorial and in production and design that they wouldn’t be able to do themselves. That way they can just focus on the comic. But sometimes that leads to them taking less than ideal deals. And it seems to me that one of the nice things about this is you all operate outside of the publisher system. You’re not a publisher.

Menard: Correct. We’re not.

And that allows you to help them get the things they need without having to rely on deals that might not be the best for them.

Menard: Totally. And we can also help them decide what publisher is the best avenue for the story they want to tell so they don’t feel like they’re stuck with one publisher. Our publishing partners are open to all that we have to bring to the table. So yeah, that’s part of it too, just being able to help the creator choose which avenue is best for them.

You have a pretty extensive background in this space. You went to school at the School of Visuals Arts for both a BFA and an MFA, so you’re not messing around. You worked as a production director at Z2. You teach printmaking and illustration yourself. You even made a pretty incredible map for What’s The Furthest Place From Here? so you’ve got all the skills.

Menard: Thank you.

There are some people who really connect to the production side of things and the design, the parts that make a project feel cohesive. You’re definitely one of them, it seems. What is it about the production side of things that just speaks to you?

Menard: It’s just so exciting. In addition to all the stuff you mentioned, I worked at Desert Island, the comic shop in Brooklyn, for a few years. It’s a small indie comic shop. Probably my favorite place in New York. And Gabe (Fowler), the owner of it, he had this great curatorial eye. There were a bunch of indie French publishers, and he was the only shop in the US that carried their work. There were these really incredible handmade silk screen hand-bound books, a ton of cool indie stuff that just really experimented with book binding and how you could present a book to the world. And I love that stuff so much. (laughs)

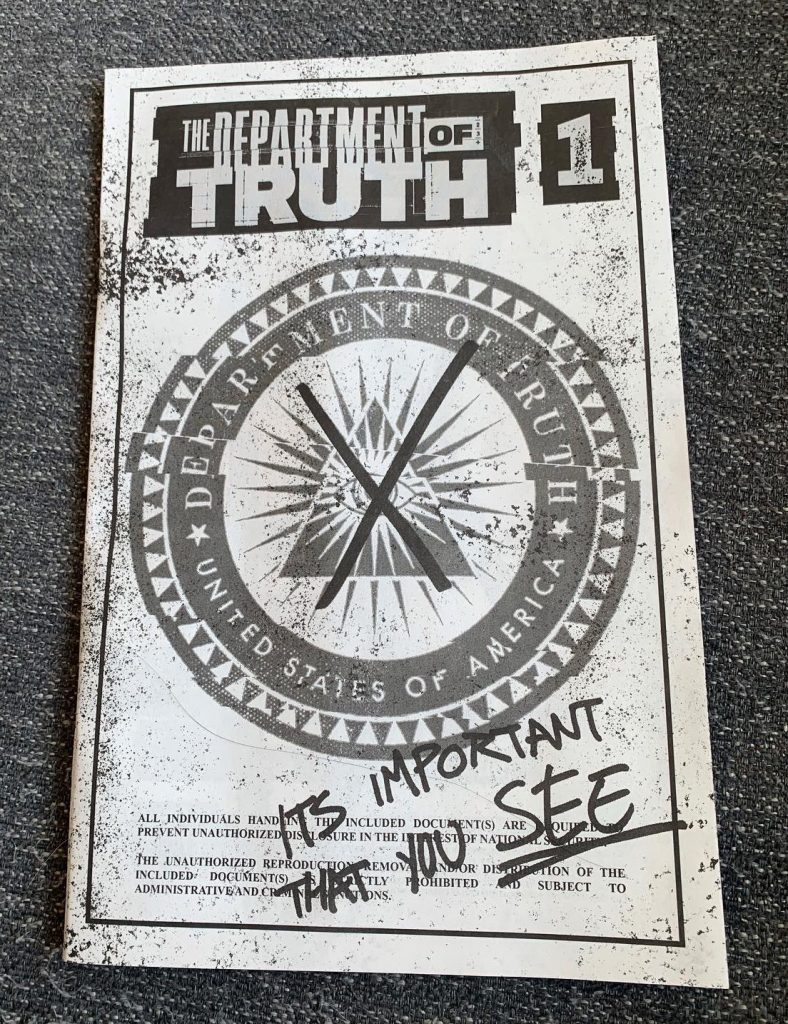

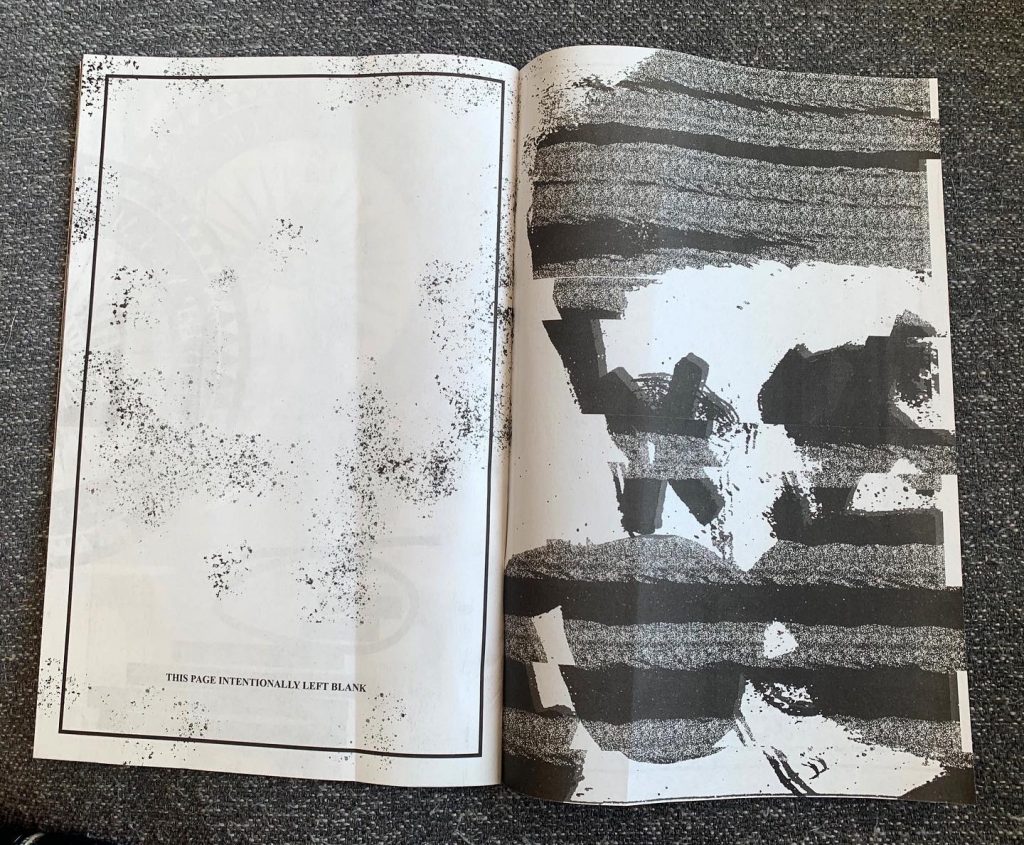

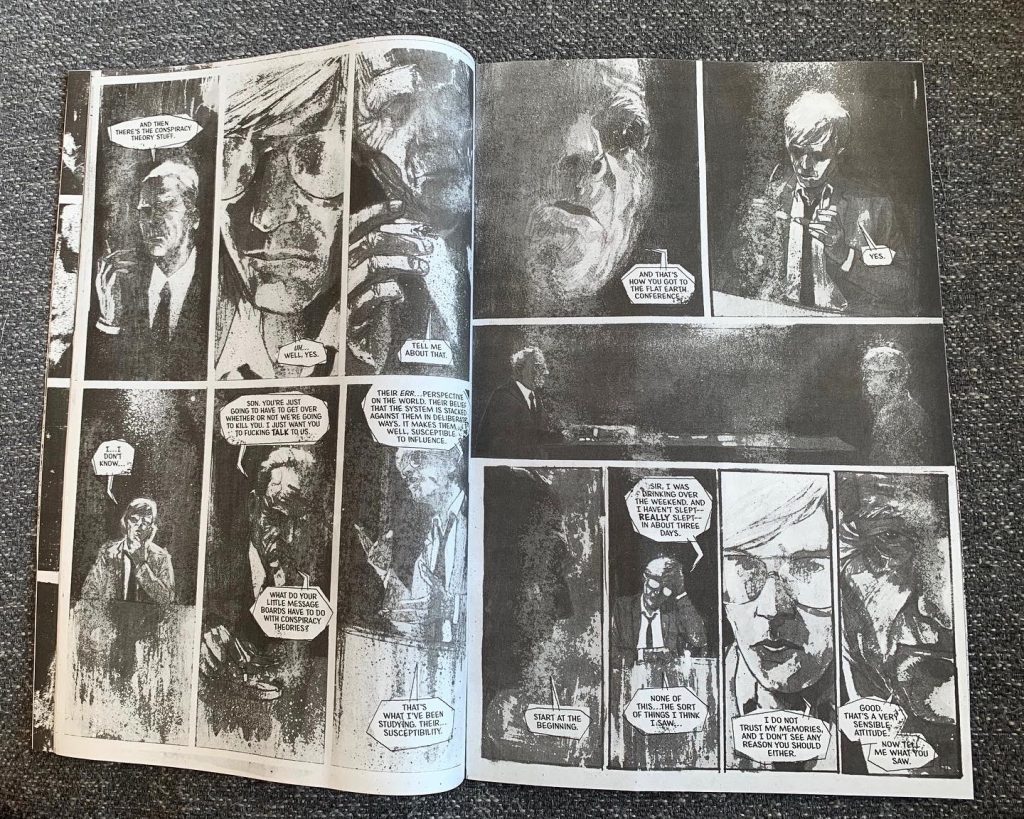

When I was in school, both in undergrad and grad school, I was print shop rat. I lived at the print shop. I was obsessed with screen printing, block printing, all that kind of stuff. The printmaking department at SVA has a robust book binding aspect to it. And for my graduate thesis, I built this big, oversized silk screen accordion book, so when you opened it, it folded out into this really long story. And I just love figuring out how to make the thing as cool as possible. (laughs) But also with intention. So, something I recently did with Tiny Onion was, we did a bootleg version of the Department of Truth. Did you see it at (New York) Comic Con?

I have it. It’s awesome.

Menard: So, the point of that was, I wanted it to feel like somebody had stolen the comic pages from the Department of Truth and photocopied them on newsprint was disseminating them to people. And so that kind of production stuff gets me excited, having an in-world object using different production methods to enhance the story.

Coming from that indie background, a lot of indie artists and publishers, people who are self-publishing or going with a smaller publisher, like Peow…Peow is one of my favorite indie publishers. They just make cool stuff and have the freedom to experiment. And I think that’s what excited me about Tiny Onion. We are independent and we have the freedom to experiment. And yeah, we’re working with publishing partners to produce stuff, but we’re also producing our own work. And I love just being able to take James’s amazing stories and the amazing stories of people in our ecosystem, and being able to just give it that extra little sense of being grounded in the place where the story is being told.

I’m going to give you a compliment for the Department of Truth bootleg edition that I think most people would think, “That’s not a compliment,” but I think you are going to take it as a compliment. It was gross. When you touch it…

Menard: Yes! Yes! It comes up on your hands.

… it comes up on your hands. And when I experienced that, I was like, “This is amazing.”

What you’re talking about that point where you’re merging design and production with what the story’s energy and vibe is, that’s the sweet spot for production, where it can make something really special. And for the Department of Truth bootleg, that was perfect, so good job by you.

Menard: Thank you. Yeah, and I love talking to Jazzlyn about this stuff, too. Because it sort of goes hand-in-hand with marketing, the way that you market the book. We do the design and then Jazzlyn goes off and markets it as this cool bootleg thing that we’ve done. And we have a bunch of projects coming up that we can’t talk about yet which we’re excited to scheme on. Building in-world and taking objects from James’s stories and kind of pulling them out into the real world, and future projects working with other creators and artists where we’re just…it’s world-building through a physical product.

And the physical product part is also quite important to me.

Have you spent much time looking and researching the best approaches and best looks in this space to help you get a better feel for the direction you want to go in advance of Tiny Onion’s debut? Are there any examples of comics that really wowed you? Because it seems like you have a keen eye for this stuff, and you’re paying attention to it all the time, and I imagine you can find inspiration anywhere, but there’s a lot of interesting production work in comics right now.

Menard: Totally. If this wall didn’t exist behind me, you would see an insane library of books. I just fucking read books, so I’m always collecting things. But in terms of projects or books that have production value that enhances the story, I’m thinking about…Adrian Tomine did his diary comic that was in the shape of a Moleskine diary. That was amazing. It even had a little embossed sticker on the back. That was super cool.

The Loneliness of The Long-Distance Cartoonist, I think it was.

Menard: Yes, that one. That was super cool.

We have the big (David) Mazzucchelli Daredevil book. Is that right? Are you about to pull it out? (David shows the David Mazzucchelli Daredevil: Born Again Artist’s Edition) Yes, that one! And it’s like, “Why make a book that big?” But the reason you make a book that big is because that’s the size that he draws at. It’s incredible to be able to see it in real life. I also have a Chris Ware compendium that has layered sheets of vellum with the CMYK’s separated so you can see it. That is exciting to me. The process stuff is really exciting to me.

Also, Leanne Shapton’s a Canadian artist. She’s done some comics, but she’s also in the prose and experimental world, as well. She did this book that was essentially built to look like a book that you would get at an auction that listed all the objects available. But the objects were all from a relationship, like a husband and wife that were separating. And so the book was the objects that told the story of the relationship. And I thought that was a beautiful way to tell the story of this couple, through the objects. So just kind of, stuff like that.

We speak the same language, obviously, because I’m just grabbing stuff that you are mentioning, as we’re talking. Have you heard of Ronald Wimberly’s comic Gratuitous Ninja, or GratNin?

Menard: I was going to bring up Ronald Wimberly, yeah. I have seen that. His LAAB newsprint paper is so cool, too.

He did a Kickstarter with Beehive Books for GratNin. There was this one that was called the Kuroda Edition. It’s in this giant clamshell case, and you open it up, and in it is a Metro Pass from New York City for one of the characters, and it’s got in-world trading cards, it’s got all these different elements, and it connects to something you said you did earlier where the entire thing was on infinite scroll. And so, it was printed accordion style. And so, you can drop it and the comic unfurls straight down. It’s just absolutely bananas.

Menard: That’s amazing.

I say this with respect to a lot of really great work out there in comics, but a lot of times, people do what you do in comics and you just have to turn the work around because of deadlines. They do the best they can within the parameters established for them. But sometimes I think people forget that there is an art to this that adds to the story experience, and I think that that is important. Also, I think that it’s important that when you’re reading a comic…like when you read a Jonathan Hickman comic, for example, that all the design elements to it reinforce what you’re reading, so it makes you feel like you’re really in that experience.

Is that one of the things you look at, as a production person and as a designer, is you’re trying to not just make this a product that sells, but also make it feel like it’s all more cohesive and whole?

Menard: Totally. The packaging of it is so important and helps it make it more marketable. So, the marketing part of it is huge, but I don’t want to design for design’s sake. I want the design to truly be a part of the story and enhance the artwork, because we’re trying to put the artists and the creators at the forefront. So, whatever we can do to enhance the work is the goal.

Do you have a sense as to what your process would be for something like this? Let’s say, obviously James’ projects are going to be…I’m going to say easier, because he’s the tiniest onion of them all. (laughs) He’s the head of all this, so he’s going to be theoretically easier to work with, because you’re in cahoots with him. But let’s say I come to you, and I have a comic I want to make with Tiny Onion. What is your approach to figuring out the right answers for a project?

Menard: For me, it’s all about backstory. I want to know everything. I want to know where the story came from, what the original idea was, and how it’s transformed any of the world-building elements. As many details as you can give. It is so helpful. I think about when I was in grad school…I went to grad school for illustration and storytelling, but we did a lot of practice writing characters and backstory, and half the stuff you would write wouldn’t end up in the story. But it’s all important so you get the sense of what the character is like, and it just makes the world feel a lot more real. And so that’s the kind of stuff that I want to hear about. Also, what is the world like? Is it a post-apocalyptic world? Is it a futuristic world?

I have a giant Pinterest board of all the design inspiration. I love a mood board. I love to do research. I have, like I said, a giant library of books I love to go back to and look for inspiration from different eras and different design aesthetics to try and figure out what best fits the story. So the process is very collaborative. Everything is a conversation between me and the creator to find out what works best for them and for their story.

What if somebody comes in with a designer they typically work with? Is that something where you’d kind of flex out of that role, or is it kind of like, my way or the highway, I rule this roost as the Director of Production?

Menard: No, no, no. Another exciting part of it is, if I’m not the one doing the design itself, I love when people come to me with the design and ideas and they’re like, “How can I make this work?” So if someone has a designer that they love working with, I also love having conversations with them, being like, “What is your vision for this? What do you want it to look like, and how can we make that happen?” And that’s the part of this whole thing that just scratches that creative itch for me, because yeah, I come from an illustration and comics creation background, but man, the production stuff is like a puzzle. I love to figure out how to make things look as close as what the creator envisioned as possible. S

There’s no ego with me about someone coming in with another designer. We’re here to support. That’s the biggest thing. I just want to support the vision of the people we’re working with.

It seems like it’s storytelling to you.

Menard: Yes, it is. It absolutely is.

You brought up the map with Furthest Place, that was my shit. Let’s draw this map, we’ll have these connecting covers, then it appears in the story, and then maybe we’ll print it later as an artifact or something. But same with Matt (Rosenberg) and Tyler (Boss) doing the records for Furthest Place. Those are kind of in-world objects too. The kids in the story have their gods, the records, and then you can have them in real life as well. So yeah, it’s all world-building and storytelling.

So, going to the 10,000 foot view again, obviously you have your own strong takes on what makes a good-looking comic, but what do you look for in a comic and its production value? What makes a well-produced comic, in your mind?

Menard: I love paper. I love how paper feels. I love getting sample paper books and covered stock paper books. It’s another reason why my house is full of different kinds of books, is to just kind of touch and feel and smell and look at all the different ways that a book is put together. And it’s really important to me that when someone is holding a book that it feels substantial. Even if it’s just a single issue. I don’t want it to feel like something you can just throw away. Unless that’s its intention. Then I do want it to feel like something you can throw away.

But I feel like the whole thing is intention. What is the purpose of the book? Is it meant to be this high-end project? A high-end art book? High-end cover art and interiors with nice premium paper? If that’s what the book is supposed to be, then that’s what it should be. It should feel premium. It should feel luxe. If your goal is something like the Department of Truth zine, that would be insane to make it on a super nice premium paper. (laughs)

You want it to be gross.

Menard: Yes, I want to be gross. I want it to come up in your fingers. I want you to smell it and feel like you’re in a dank room in a basement talking about conspiracy theories. So yeah, what makes a book produced well depends on the book. I feel like I can tell if something was made just because this was the paper that was available and that’s all we could use. You have to dig a little deeper.

I completely agree. That’s one of the things that I think is interesting about the comic world…you brought up Peow. Peow is a great example. I just did an interview with Avi Ehrlich from Silver Sprocket.

Menard: Ugh. Love those guys, too.

Avi was talking about Peow and saying, “Peow used to be my standard for making a great-looking book, and now it’s France.” Avi just went to Angoulême and was blown away. But the more your world expands, the more you can see comics executed incredibly well. One of my favorites is ShortBox. I love Short Box and how they’ll do spot glosses or foils on books, and it just makes it pop that much more. When you hear foil, I think a lot of comic fans think of X-Men comics in the ’90s, but it’s considerably more thoughtful than that, even though I have a special place my heart for the ’90s stuff, too.

Menard: Of course.

It is interesting where a lot of the work people in your space do is the type of thing that I don’t think people engage with in a necessarily conscious way. People aren’t really actively engaging with it, so it seems to me that you have to consider on multiple levels where you have to kind of balance between making the best product possible but also not making it cost prohibitive, to some degree.

Menard: Totally. That’s a huge challenge. It’s honestly less difficult than you would think. There are little things you can do to make something feel more special. A spot gloss already makes something feel more special. Just a slight up in raising the weight of the paper one point, can make things just feel so much better. But I would also say that sometimes the mark of a design being good is that you don’t notice it. It just feels inherent. You definitely don’t always have to go like…am I allowed to say balls to the wall?

That’s the exact phrase that was in my head.

Menard: You don’t always have to. I keep going back to the Department of Truth zine, but that was so easy and quick to make because of the paper it was on and because it was one color. This is the thing we talked about a lot at Z2…the production of books and keeping things in a budget, because we did super deluxe collectible versions of our books. That was real world-building stuff. We did a Mötley Crüe book that came in this clamshell box that looked like a safe, because the whole Mötley Crüe book was about them being secret CIA agents or whatever. (laughs) It came with like their CIA badges and with a map.

That’s awesome.

Menard: It was pretty cool. It came with a map that had UV ink on it, and then we made these pens that were blacklight pens, so that you could see the secret message in the map and the secret code. And it is a challenge to find how to make something super cool and make it feel real, and not just a cheap thing that you could find online. You want it to feel real, but you also want to not spend a million dollars to do it.

I can see why you get excited about this stuff. With that Mötley Crüe thing, I imagine just the concepting phase of that was probably a blast, just throwing ideas like, let’s turn it into a safe, let’s make IDs, let’s throw in a map.

Menard: Yeah. And that’s the kind of conversations me and Jazzlyn and Eric and James are having right now about these future projects. We’re starting from a place of like, what is the most insane stuff we can do to make this the coolest project we’ve ever done, and to engage the fans and to make sure the creators are getting the product that they want. And then if we have to pare down, we can, but it’s so exciting to be able to dream sky high with this kind of stuff. It makes me so happy.

My day job is an advertising agency, and one of the things you want to do is you want to go to people with a pitch that’s going to wow them, but you also have to be realistic about it, so you can always start with the wow and then scale back, right?

Menard: Yeah, for sure.

It seems like you work pretty closely with the rest of the team. Do you find that there’s a lot of interaction between you and Jazzlyn and Eric and James in the process of building out what Tiny Onion is and what the books can look like?

Menard: We’re just a small little crew and we’re remote. But despite being remote, we have a Discord channel, and so we’re all chatting in there every day, talking about what we’re working on, talking about our projects. And because we’re so small and because we’re remote, it’s really important that we’re all in sync with each other. They’re some of the most delightful people I’ve ever worked with, and they’re all very good at their job, and I feel honored to be working with them.

And then also, it’s important to get the face time too. So we’ve been having summits once a quarter, we’ll go to New York and hang out in James’s apartment and just have this giant three panel whiteboard where we just toss everything up and talk about how each of our departments are going to interact to make projects happen. And it’s just really fun. It’s been so inspiring and cool to work with these guys.

How long have you been a Tiny Onioner?

Menard: Technically since the spring of last year. Yeah. But officially since November, I want to say.

You had to precede New York Comic Con, because otherwise you’ve been doing very free work for making a very not free bootleg.

Menard: Yes.

I think one of the cool things about this collaboration is you work in production design, but if Eric comes across something that’s cool or James comes across something that’s cool or Jazzlyn does, they can send it your way. And I imagine you’re not just taking inspiration from comics; I imagine you’re looking outside of comics and finding things anywhere. “Have you seen what they’re doing in this magazine?” or whatever. Inspiration can come from anywhere, quite possibly even your teammates.

Menard: Totally. They’re all just very excited. The thing we say to each other the most is that we just want to make cool shit. And so we’re just always sharing cool shit with each other, and we all come from a slightly different space. Eric was at BOOM! for so long. James has obviously been in all different types of spaces in the comics industry, but he was at DC forever and now he’s doing creator-owned. Jazzlyn comes from a merchandising background, and then my background is more indie comics, and so I’m not as well-versed in the mainstream and stuff as James or Eric is.

And so, it’s cool to exchange the information about what cool stuff is happening in mainstream comics and what cool stuff is happening in indie comics and what cool movies we’ve seen, and how their marketing scheme works really well, or even what’s cool in fashion right now, and how is that influencing our work? It’s just a big web of cross-referencing each other and it’s really fun.

I know that you said that there’s going to be a tailored approach to each project, but I think one of the things that’s interesting is, even though Tiny Onion isn’t a publisher, it seems like it’s important to have an identity to Tiny Onion as an entity. How do you balance those two sides? Is it about developing what’s a constant and what’s a variable, and building from there? Like, let’s say I come in and I’m like, “I want to do a book with Tiny Onion.” Are there going to be elements of Tiny Onion on each Tiny Onion book, even if it’s not a publisher?

Menard: We do take a curatorial sense of the projects that we bring on, and we want all the books produced under the Tiny Onion umbrella to be…not similar, but to have kind of the same sensibilities. So in-depth world-building, a lot of James’s stories are horror, or he has the cryptid line, those kinds of things. So, stuff that kind of fall in the same areas, genre-wise, as stuff that James puts out, is the kind of stuff that we gravitate toward working on, and that I feel will kind of become our brand calling card.

In similar ways, speaking of video games, Jazzlyn was talking to us about Annapurna, the indie game publisher. They’re sort of similar to us in that they take on different video game developers and then publish their games, but everything kind of feels of the same universe. So, I think the universe-building is going to be kind of the Tiny Onion’s brand and calling card.

How do you reinforce that from a production design standpoint, though? Because Annapurna has Annapurna Interactive show up in front of every game. Are there going to be consistent brand elements that will, no matter who’s making the book, show up on the projects?

Menard: Yeah, our logo will show up. The discerning reader may have noticed a credit inside of DSTLRY’s most recent books. A little Tiny Onion, “packaged by Tiny Onion Inc.” credit.

For all of them?

Menard: Yeah.

Oh! Whoa. Sneaky.

Menard: I know. Very sneaky. So, we’ll have a presence. In terms of design sensibilities, I do want each project to stand on its own and have its own strong personal branding, but the Tiny Onion logo will be there, more as a stamp of like, we think this is a cool thing that you should read. But I do want each story to have its own voice and design aesthetic.

So, it’d be less about specific branding elements besides the Tiny Onion itself, and more about the kind of general ethos that’s guiding it from a production and design standpoint.

Menard: Sure. I want the calling card to be that it is designed beautifully and produced beautifully. I want that to be the thread.

And good paper stock.

Menard: And good paper stock. Oh my God. I have this drawer in front of me and I have all these little paper sample books, and I love it. You have no idea.

Why is good paper stock something that’s so important in your mind?

Menard: I don’t know. It’s just how it feels. I hate picking up a book and there’s immediately fingerprints all over it, or it just feels like it’s so fragile that it’s going to rip. One of life’s small joys is going into a stationary store. There’s this amazing stationary store Yoseka Stationary in Greenpoint, and they just have shelves and shelves of all these different kinds of notebooks and papers and pens, and it just feels special. It feels like it was thought of, like it was loved, and when you pick it up, that’s the feeling that I want transferred to the fan. That this book was cared for.

This book was thought out in every aspect. In the story, in the art, in the production, in the writing, in the marketing. And paper stock is so important. Also, just coming from a printmaking background, paper could make or break your project. If you’re silk screening on a paper that’s not good for silk screening, your project sucks. So that has turned my eye into checking out paper.

It seems to go back to, I said ethos earlier, but it seems like, there’s another word you said that’s important to all of this. You said, “intentional,” it seems like one of the big things for you is, no matter what project it is, it has to come out seeming intentional in the production design.

Menard: Absolutely. Yeah.

And that’s a core thing for you.

Menard: Yeah, definitely. I don’t want every project to just go through the same steps that the project before it went through. I don’t want anything to feel dashed off. I want each project, when it’s done, to have its own story of how it got to look the way it does and how it got to feel the way it does. Because the artists deserve it. The creators deserve it. They deserve to have their stories look and feel as good as they want them to. They deserve to have the behind-the-scenes team working as hard as they work, because making comics is hard.

That’s one of the things that I think is interesting. I mentioned how a lot of times, people are not very conscious of this sort of stuff, but I feel like when you come across good production value and you come across good design in comics, you really do notice it.

Menard: Totally.

This is very mainstream relative to a lot of the stuff we talked about, but when Marvel did House of X and Powers of X with Jonathan Hickman, those books looked different and felt different for a Marvel comic. And because of that, I think fans felt they had to pay attention to it. It stood out. It’s like glaring red lights that are blinking at you, saying “Pay attention to me.” And it’s not like you always want to be showy or something in what you do, but you want people to feel that Tiny Onion means something different.

Menard: Absolutely. I think of Jordan Peele movies, where every time I see a Jordan Peele trailer, I’m like, “I have to see it.” I think that he’s got a great vision, and that’s what I want our books to feel like.

I presume you’ll be working across all print projects, so not just single issues, but collections and beyond, right?

Menard: Correct.

What is your purview?

Menard: It’s everything. The production department right now is me. I’m the whole department. (laughs) So it’ll differ from project to project, in the sense that it depends what publisher we’re working with. So, we have so much control over our Image titles and what those look like, whereas it’s different with BOOM! BOOM! has their in-house staff working on producing those books.

And honestly, James has been doing this for so long that a lot of the ongoing titles are just well-oiled machines that are functioning pretty perfectly. I’ll come in every once in a while if we’re doing a special variant cover or something to do some design or give input, but right now our bread and butter is going to be the hardcover, the art books and the trades.

James did a Kickstarter last year, the Room Service Kickstarter, and that includes the movie, which looks fucking phenomenal, and then all these extras. This is the kind of world-building stuff that I really like, so I’m doing all the production on the Kickstarter extras. We’re doing an art book, and so I’m producing that, and I was like, “How can we make this art book feel like it’s of the world?” Even the way we’re shipping it out to Kickstarter backers, what does the unboxing experience feel like? What’s the first thing you see when you open the box? What color is the packaging materials? All that kind of stuff.

And then our partnership with DSTLRY, working on all their single issues and producing all their single issues. So, I have my hands kind of everywhere right now. As we’re ramping up, we have some more in-house projects that…we’ll follow the single issue to trade paperback route, but we’ll have some other surprises along the way that we’re very excited about.

I’m sure that you’ll have special projects from time to time, too.

Menard: Sure. We love a special project.

How excited are you for people to see what you’ve been cooking up? Because it’s like, even the DSTLRY thing, it’s one of those things that was hiding in plain sight, but you’ve been kind of secretly doing stuff. I imagine you worked on The Deviant, even, because that came later on.

Menard: Yeah.

Are you excited for people to really know the shape of this thing that’s been part of your life for a while now?

Menard: Yeah. It’s so exciting. And when you’re in a thing and you’re excited about it, it’s sometimes hard to take a step back and see if everyone else is as excited as you are. (laughs) But I think they are. James is a huge part of it. James is excited. He’s all in on this. His excitement is palpable, and just transfers so easily to everybody else. He just has this excitement and vision for the future of comics that I don’t think a lot of other people have, and I’m just honored and excited to be able to be a part of it. I’ve said excited 12,000 times, but I’m ecstatic. I’m stoked. (laughs)

I can’t wait for people to see what we’re doing.