SKTCHDxTiny Onion: Part Eleven, Managing the Social Media Environment

What a strange time it is.

Okay, that’s a little too vague of a statement, because it’s such a strange time in, like, five million different ways. So, let’s be a little more specific.

What a strange time it is to be a person, or, to drill down even further, to be a comic book creator as the social media ecosystem is collapsing. Twitter doesn’t exist anymore, with X being the palest of comparisons. Potential replacements like Threads and Bluesky are flawed in varying ways, with other theoretical substitutes not even being worth mentioning. Other platforms — all platforms really — struggle under the weight of algorithms that make them seem unpredictable at best or broken at worst. And when you’re a comic book creator in 2023, someone who is often not just expected to craft the work but to bear the brunt of promoting it as well (typically through a following you’ve cultivated on these platforms), it can be incredibly challenging to do so successfully.

That’s the just tip of the iceberg in terms of the cost this is having on creators. Social media has helped them build relationships, get jobs, gain fans, and any number of other things that are crucial to their careers. Losing that, or — perhaps even worse — retaining that in a neutered, more time-consuming fashion, is painful. Because of that, creators are talking amongst themselves (and publicly) about the cost of these changes, while making some themselves. The list of those adjusting their approach includes writer James Tynion IV. While he hasn’t necessarily spoken publicly about the impact these changes have had, to this observer, it’s been clear he’s been shifting his approach on social media and other public facing platforms of late.

With all that in mind, I thought it made sense to dig into this subject for our penultimate SKTCHD x Tiny Onion chat, so that’s what we did. Tynion and I hopped on Zoom to discuss why he’s been dialing things back on social media, the evolution of those platforms (both throughout time and within your career), what hasn’t been working, where newsletters fit in all this, his plans for the future, and more. It’s a great conversation, and one has been edited for length and clarity. It’s also open to non-subscribers, so if you enjoy the chat, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more like it. Lastly, this chat is a co-production between Tynion’s Substack and my site, so if you haven’t already, make sure to subscribe to Tynion’s newsletter to keep up with what he’s up to in general. That’s enough preamble, though. Let’s get to the chat.

Comics marketing has been a big topic of late, as has the ongoing downfall of social media. Those are obviously big topics for creators. It’s about getting their work out there and getting people excited about it. That’s part of the job these days. That’s what we’re going to get into today. I know you have been rethinking your approach to social media. You just locked your Twitter, for example. What’s led you to dialing things back a bit on social?

James: I mean, a lot of it’s just personal sanity. But I also recognize I have a freedom to do that because I have a few things going for me. I have a few series that are running at a consistent enough sales level that that influences the sales on my other books. As long as Something is Killing the Children is selling reasonably well, I can expect that most of the other series that I launch are going to launch and maintain decent numbers, which is an extraordinary privilege that I don’t balk at.

But honestly, social media is something that I struggled with my relationship with for a long time as a creator. And there was no period at which it was worse than when I was right in the middle of working in superhero comics. There are just so many things that are put on you as a creator. You basically stand as an avatar of a company like DC Comics. And you sometimes have to withstand decisions that you did not come by yourself. You’re not going to throw your boss under the bus. You’re not going to throw your friend under the bus, even when those decisions piss off the fan base. And then at the same time, it’s the knowledge that you have to build up an audience that you want so then that audience can come and buy your other books.

I want to have a good relationship with my readership, but it felt less and less like social media was an effective platform for that in any real way. And so, I started pulling back from Twitter around the time that I launched my Substack newsletter, almost two full years before the Substack Pro Grant. And it was just like, “Okay, now I’m building out a newsletter where I can directly message to my readership about what I want them to know,” and especially having the freedom to do that across different publishers.

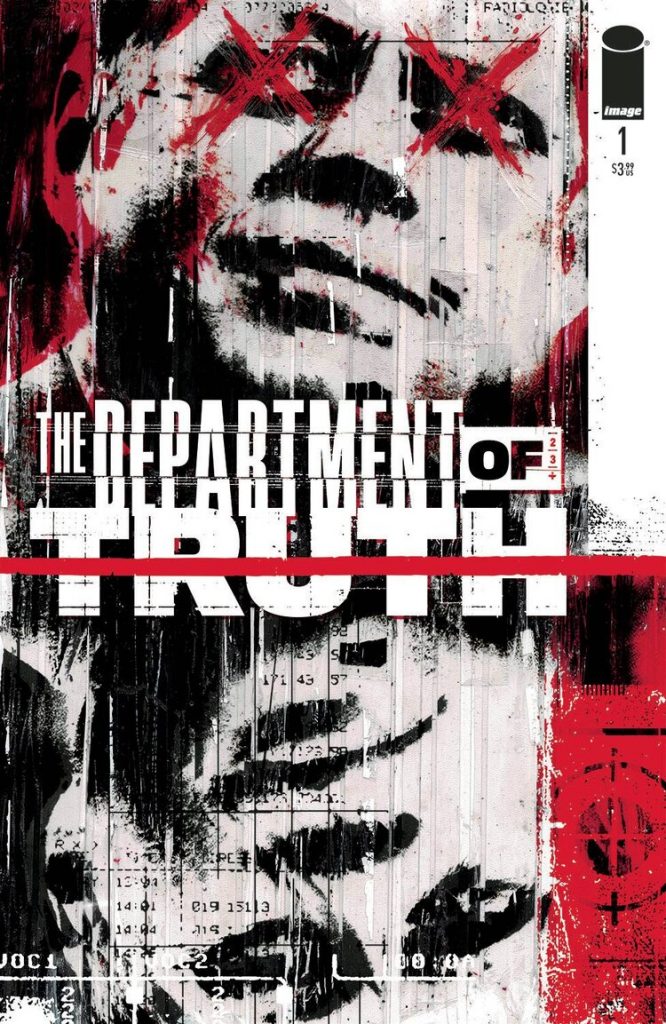

The thing that I always point to is I saw the math on the table…I had just launched Something is Killing the Children. It had exceeded expectations and was selling a bunch. I had just been announced as being put on Batman and I was going to be launching an Image title in the fall. And no one at any of those three companies was going to tell the escalation story of Something is Killing the Children to Batman to Department of Truth. But I knew that there was a story to tell, and I realized that the only way to tell it was to tell it myself, and that the best platform to tell it was in a newsletter rather than in just short soundbites that get drowned out the second you’ve finished posting them.

You said you come from a place of privilege, but your career has actually kind of coincided with social media becoming ubiquitous. It was kind of a niche thing before then, at least to some degree. Over your career though all those different platforms became powerful messaging platforms. They became powerful promotional tools. How much do you think the impact and importance of social media depends on where you are in your career? Does that make a major difference?

James: The real answer is that it has changed every two years since the start of my career. I am 35 years old. I am peak millennial, just born in 1987. I was in high school when Facebook stopped being a college only website. I was in college when Twitter launched. I was an early adopter on both. I was a big Tumblr kid. A lot of my peers were very big on Tumblr, especially on the art side early in our careers. And it was one of those weird things where I had the niche interest in those spaces in superhero comics as opposed to all the other types of comics I like and engage with. But I was very much a part of that generation and came into the industry alongside that generation.

When comics Twitter took center stage, and I would say around 2008 to 2012 is sort of when that really happened, I kind of got to be at the forefront of that. Not in any prominent way because it was only right at the end of that that I became a published comic author. I didn’t have a lot of followers or anything like that, but I understood the language of the platform, participated in the platform, and I liked talking on that platform.

I grew up in Wisconsin, but then I went to Sarah Lawrence College and then I moved into New York City. It was just all these things where it’s my friends were distributed all over the country and here’s this silly website where we’re just posting a bunch of dumb shit and being emotionally deranged and mopey and all of the stuff that we had always been online.

And then it was bizarre, the shift of that. For a while it was empowering to kind of like, “Okay, I’m going to be this very authentic version of myself and I’m also going to try to sell people a comic book.” It was before the term influencer really kicked off, but it’s just like, “Can you become a kind of comics influencer by having lots of opinions about it?”

And that’s when things started to tip into, there was a lot of grandstanding. I definitely participated in some grandstanding. And most of the time it’s in the moment I felt very passionate about the stuff I was grandstanding about. But then it’s like afterwards you sort of question, “Is this something that I actually cared about or is this something that I saw a moment where I could get a bunch of engagement and likes and all that?”

The priorities started shifting. Alongside that timeline, I was also sort of grappling with what sells and what doesn’t in comics. And there were whole generations of comics, especially as the medium started catering a little bit to the voice of comics Twitter, where it was apparent that it’s an insular group that’s a small part of the industry. It’s hard to turn that into a sales driver.

A rule of thumb that I’ve been saying for years, and it’s probably sadly much less true today than it’s ever been, but I always saw social media as…if you build up a good social media following that can add up to somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 in sales. If you are an indie creator, the self-published indie creator, that’s make or break. That is huge. Even if you’re on a creator-owned book, those are real sales.

But the issue is once you’re up in superhero comics land, those sales don’t even affect whether a book is canceled or not. It has next to no effect. And then it’s just seeing more and more of my peers spending more of their time trying to build up the kind of persona audience without figuring out how to reach more readers and build more sales. And I think people take the wrong lessons of what is successful and what isn’t in that space.

At the end of the day, especially if you’re trying to go for anything close to mass market appeal, you need to know who you’re selling to. That is the primary thing. And see, I hate the framing of this though, because as I say this out loud, it sounds like I’m making a culture war argument, which I’m not. It’s all of this gets framed in those terms, which I think is a nonsense bullshit frame for it, but because it’s just another insular lens to put on the whole thing.

I don’t know. I have lots of thoughts about it. But the moment I was spending too much of my time thinking about how a little silly joke I was making on Twitter was going over, or did I say the right thing in the right moment on Twitter and all of that versus, “How do I make this story? How do I improve my craft and how do I sell five more copies?”…it was just like, what is the thing I should be putting time and energy of my own brainpower into?

It seems the more popular you get, the more followers you get, the more eyes you have on you, the more chances there are for things to go awry or things to go well, one way or another. Did you find that the further you went up, up, up in followers, the more you shifted away from personal posts and more towards the promotional? You found that most people wanted to follow you for your writing, and so you wanted to make sure they could have it and it was also the thing that was most beneficial for you really?

James: Well, yes and a no. I think as I rose up in superhero comics, I definitely started pulling back more and more of myself on Twitter and just how much of my honest self that I was putting forward. But in what’s left of my social media footprint today, I’m trying to get better at promoting the books again. Frankly, at this point, it’s all my gym selfies and me hanging out with my friends, which is like, honestly, that’s what social media is for. Social media is actually about hanging out with your friends and getting to see what your college friends back in Wisconsin were up to this past weekend. That is actually the function of social media.

It’s social.

James: Yeah, and there’s still incredible value in seeing that and getting to engage in my friends. And honestly, I love art. I love comic book art, illustration, tattoo art, and so I love seeing what all these different people are up to. It’s an incredible discovery engine when it works properly. And all those things were great. But it unlocked again with me with the newsletter when I started being very personal again with my online engagement. And it felt much more natural to me because I started my relationship with the internet on message boards and LiveJournal when I was in high school. I’ve always been a moody, weird emotional kid, and my books are personal. I don’t put up the walls there. I put a lot of the ugliest parts of myself in my books.

So, I feel more okay being a little more raw and a little more human in a little more of a public way. But there was something very different when I was…There’s something about when you are working in corporate comics under a big banner like DC that you become a sort of politician representing DC and the region around DC.

Like when you’re handling Gotham.

James: Yes. But that doesn’t mean you have any actual control over it, and half of the things that are happening you don’t agree with. Or half of the things you did agree with when it was a raw idea, but the execution of it happened in the opposite way if you would’ve done it. But you want to support your peers, you want to support all this stuff, and it’s just becomes this…I don’t know…it became very hollow because it felt like it wasn’t… When somebody following me wasn’t able to tell what is me actually reacting to something I feel strongly about and what is the thing that it’s like me just saying a two-faced politician thing. It felt bad. It felt really bad and it consumed me.

I have this sort of personality…you can see this in my output. I fixate. The thing that is making me anxious will just cycle through my head over and over and over and over again. There were moments where things politically… I mean right now is another moment of that where if I’m spending too much time on social media, I will just spiral and get swept up in it, and then it’s in feeling small and anxious in the face of the world.

It’s like feeling like a little statement’s going to do something when the real emotions are what I want to sit with. I want to take those thoughts and internalize them through my reading and all that, and I want to express it in my art. That is the actual how I want to process the world and how I want put myself out there. What I’m trying to put out on social media is very different than that. I do want to use it as a sales platform, and I do think it’s now different that I’m in the creator-owned space. I do think it can function a little differently and I can be a bit more authentically myself and I don’t have to worry about being the figurehead of a corporate entity in the same way.

Yeah, you’re in control of what PH34R does. Nobody else is. Well, Fernando and everybody else.

So, we talked in the beginning about how you’re dialing things back. In my conversations with people, a lot of the stuff that used to work well on social media isn’t working as well. Is there anything that you’ve noticed isn’t working, old tried and trues that are struggling in a way they haven’t before, or is it broader than just specifics like that?

James: Oh, absolutely. Right now, have just under 60,000 followers on my main Twitter account. I would say that I was in, let’s say the mid-forties while I was in my Detective run and then climbed up into the fifties once I jumped on Batman. At that moment when I would throw out a random thought or idea, I would get a significant amount of engagement. I had a high follower count, I was engaging with other people with high follower accounts. The algorithm was weighted in favor of my posts, and it was just very apparent that it was a decent messaging platform at that time.

But the second that I really needed it, which was the moment that I moved over into creator-owned comics, it felt like they started turning all the knobs on the algorithms. If you had a selfie of yourself or if you just had an emotional statement about a thing, those posts were always weighted way more heavily than actually just promoting a book that you have coming out or something like that, which makes sense on a certain level because it’s always weighted towards things that people are going to engage with more.

But then it’s become something where it felt very much like it’s trying to make you engage more with the machine. The goal of Twitter stopped being for it to be a portal to the internet but to be the place you go to and stay in. And I think that this is the problem that hit all of the different social media platforms. I think now, as it collapses as the center stage of the internet, it’s because every site tried to become the entire internet in one site, which no one wants. That’s not what anyone goes to the internet for.

The thing that has been the most remarkable, because, basically when I launched with the Substack Pro Grant, I was off Twitter for probably a year, year and a half fully. I locked the account and I didn’t come back. And when I came back, it was different.

Did you really see the change?

James: Yeah. When I came back to just promote the FOC (final order cutoff, the last point shops can change orders for a comic) of a book…I forget which one. Even though I knew my circumstances in the industry had radically shifted, my sales numbers were up, but the engagement had gone to next to nothing. It has stayed there. I come back every now and then to bang the drum, but the peak engagement I’ll get on a post is a few hundred likes. When I posted my before and after picture of my weight loss that got a few thousand likes, but nothing to do with my comics career.

I like having Instagram because I can post comic art every now and then and I can post my gym selfies, and particularly, I can post them as stories which vanish in a day. That feels like it shows my friends what I’m up to. It shows the readers who want to know what I’m up to what I’m up to. But I’m still trying to solve how do you message things using these platforms that used to honestly be quite good at messaging.

This is an obvious thing to say, but I’m going to say it anyways. I find that the more I like what I’m putting out there, in the sense that I feel more myself on social media, the more I like the experience. Instagram is actually kind of nice because I can use my personal account to post pictures of great food or my cats, or I can use my SKTCHD one to post pictures of really cool comics I got or art I have or things like that. And it’s me expressing things I’m excited about in just a purely image-based way. It just kind of makes me happy in a way that the other ones don’t. It’s interesting how the image focus of Instagram has this better feeling about it now versus the other ones, and it seems like you’re going through that too.

James: Yeah, absolutely. I wasn’t expecting that to happen. A lot of it was I pulled back from Twitter again. I wanted some kind of broadcast platform, especially because I’m going through a tremendous body transformation and all of that. Honestly, so much of the selfies is, it’s my own weird form of… It’s me not believing as I take a picture of myself that I like a picture of myself. It’s a little self-indulgent. I am not trying to make it out to be like there’s nothing self-important about it. I mean it’s a little self-important. (laughs) But I like it. I like doing it and I like hearing nice things from my friends on a day that I think I look cute. (laughs)

Before we started recording, we were talking about your (physical) run times improving. It’s the visual equivalent of that. It’s a before and after. You get to see how you’ve changed, and that stuff is super meaningful.

You mentioned your friends. As things have splintered and Twitter became X and people moved to Bluesky and people moved to Threads and people have shifted to other platforms and done all this stuff while also being on the original one, I’ve heard a lot of consternation about it. But in your conversations with friends, is this something that people are talking about or is it less of a concern and more just something that’s happening?

James: It is a massive concern because right now we’re in a moment where it doesn’t feel like either of the Big Two let you…There isn’t the same kind of star making happening at the Big Two right now where creators are being given a chance to really shine and elevate themselves with a marketing apparatus of a big company that’s centering them and their vision and all of this stuff in a way that was very common back in the 2000s and 2010s where it was all very personality focused. It was about all these big personalities and there was a benefit to it. It was like which of the big personalities did you see most of yourself in and then what books do they like and all of that stuff. Communities would sort of would spring up around that.

And then when that started going away, it went away in favor of this self-promotional system on social media, which had a lot of flaws. There were a lot of bad habits that came from that. But at the same time, if you built up a modest following and then you wanted to Kickstart one of your books, you would be able to fund your book. And now the field is so crowded. Kickstarter links are unweighted, or they’ve been given negative weight, which I saw up close and personal when I did the Room Service Kickstarter last year. The engagement on posts that had the Kickstarter link in it were dead in the water. I had to sort of trick the algorithm into letting me post things that would lead towards the link so people could buy a thing. And I have a fairly substantial platform and it was like that.

But my newsletter drove 75% of traffic towards the Kickstarter and another 10% came from the Kickstarter algorithm itself, not from social media. So, it was just the fact that what had worked in the past wasn’t working. It’s scary. I’ve seen a lot of my peers try to build their own one-on-one relationship with their audience, which is similar to what I’ve done with my newsletter. That’s the whole key.

Before we started recording, we were talking about some of the doom and gloom stuff surrounding comics. And it is interesting to think about the natural pathway of publishers creating these big names and then being like, “Oh, we have these big names and we have this social media thing. We can get them to promote the books instead of us having to do it.” And then the social media platforms started falling apart and next thing you know, they’re not as effective. And then basically the marketing apparatus for comics has fallen apart. It feels very directly connected to one another and the current state of things where it’s tough to make a hit right now unless you’ve already made hits like yourself.

James: Yeah. I think we’ll get through this moment, but it’s a frightening one and the systems aren’t built for it. And on top of that, because it’s 10 years of the big companies relying on creators promoting themselves rather than actually putting the money into the promotional work on their end, that apparatus has been stripped down to next to nothing at both of the big companies.

It doesn’t even feel like they know how to sell a comic at a certain point. They can kind of remind you of when a comic sold in the past. It’s like, “You should order this like this other book you remember,” or it’s just like, “You should order another success from this creator.” But in terms of giving retailers and readers an actual line in, there just isn’t the same roadmap.

I don’t know. Honestly, it’s a scary moment in that regard. And that’s part of what led me to start doing all of my own marketing. I took a lot of trying to sell the books onto myself because I didn’t particularly trust the companies to do it. And it isn’t against any of the people working at the companies, it’s just like there’s too few people, they’re overworked, and then on top of that, there aren’t effective platforms anymore for them to do that work.

Social media isn’t an effective platform for it. All of what used to be the big cornerstones of the comics internet and the big websites have been turned into clickbait farms. And then on top of that, before they were turned into clickbait farms, their audiences had dried up. First social media took the audiences from all of those websites to put everyone in the central space, and then it stopped functioning as a central space. But then those sites have been devastated.

And so, it’s really all that’s left are direct relationships between creators and their existing readership. And there’s no longer a functional discovery engine like sites that point you towards new books. Because this is the thing, if everyone’s sending the same promo materials to the same couple of places… This was the issue with not the current era CBR, but the era directly before that, where it’s kind of got to where Wizard landed at the end. You couldn’t really trust what was being highlighted and starred because it felt like they highlighted and starred everything.

How can you, based on that, figure out “Oh, this is what everyone agrees is the best book right now.” Right now, there is not a good engine for finding out that everyone agrees this is a good book. That’s hard. And now it’s coming down to we’re all off in newsletter land and Patreons and all of that. Honestly, that is where I find out about new books and stuff. It’s just like if Brian K. Vaughan says this is something that I should read, I’m going to go check it out. But it’s just not like it used to be. I’d see something cool pop up on Twitter and then I would add it to my pull list. It doesn’t feel like that happens anymore.

You were talking earlier about how there’s the siloed nature of these different platforms and everything like that, but newsletters are the same. Everyone’s got a walled garden of their own now. It is horrible to think about all this though because as you talk about it, you just see how interconnected all these things are. Because another factor in all this is just there’s more comics than ever, and how do you promote all these comics when there’s no real hub website to go to and social media has fallen apart. Trying to gather all this together is difficult.

James: And then I’ll add one more thing even on top of that, which is the fact that none of these books pay well enough, so everyone’s working on twice as many books. So even if you are a fan of a creator, unless you go all in, you basically have to pick. Even a rising creator, you’re not going to be able to read all their books on top of everything else that you want to read.

You mentioned bringing things on yourself. Even though it’s a walled garden, that I think is the main reason why newsletters have become so much more important over the last four or five years. Being able to have a direct line that’s not algorithm driven with your readership, with your fans, with all that, and then being able to drive them towards the things you’re doing and build awareness in that is, even though it’s not a path to discoverability, it’s a good path to activating your base, to use a political term. And it seems like that is an increasingly important channel, not just for you, but for pretty much anybody who uses them.

James: 100%. One thing that’s helped me out a lot is I know a lot of retailers follow my newsletter, so they are aware of what my newest books are. They get little sneak peeks of what’s coming next. So even though I have a high output, they have a sense of what’s coming from me. What I think I’ve successfully managed to do over the last year, I did a whole post one year after the Substack program where I was basically like, I need to stop writing newsletters as a career because I’m not trying to sell a newsletter. I’m trying to sell comic books.

At some point I’ll probably reopen a pay version of my newsletter. I now have more resources to let me create interesting content that I didn’t have time for when it was just me. And the value of that is direct sales. We are in the direct market. Direct sales matter tremendously. The big thing that I always try to get through to my friends who are rising up in the industry is you need to develop relationships with the shops that sell your books well over time. And then you need to keep leaning in. You need to make sure that you have good relationships with those shops. Then you have to keep those relationships good because they’re the first line of defense.

Now that I have a whole library out there, the math of it changes a little bit because I don’t need to worry so much about, how much does Something is Killing the Children #35 sell because the sales of the first few volumes bankroll the whole thing. And honestly, that’s still true of Department of Truth and a lot of things. Once these systems get up and running and then once they actually penetrate into the book market and all this stuff, there’s all of these added things that start happening. But you have to survive until you get to that point. And before that moment, you have to make as many direct sales to your audience, and who are you selling to?

The retailers are the most important people you’re selling to.

Did you tell retailers to follow you on the newsletter or is that just something that happened?

James: I think it just started happening. But there are things that I started doing that were deliberate in that way. That’s part of why I was doing direct sales with Razorblades (A Horror Magazine, the digital horror comics anthology) when I launched that. I knew the shops that were going to most actively follow me on social media and on the newsletter were the ones where it was up to me to try to get a few copies to sell in their shops. And I sold it to them at wholesale rates. This was before I had distribution through Third Eye and all this stuff.

I shipped the first one out of my apartment and that built some direct relationships. And then beyond that, it also started telling me, “Okay, where are the parts of the country that my books are selling really well in and where are the places that are interested in a weird thing like Razorblades?” Razorblades was an outside the box thing, and I wanted to know all of that information. So, it was little tests like that, and then it’s tests on the collector front with my Onion Club and things like that.

And I made a million mistakes in all of that. But all those mistakes are worth it because it was identifying who are the people who spend a lot of money on the idea of James Tynion every single month. Honestly, one of the biggest reasons I have such a big partnership with Third Eye is that my books do very well in Third Eye shops. And so it was just going down and understanding the base audience of Third Eye as a chain, which is one of the most successful comic chains in the entire country. And it was just like, okay, I want to pick apart what is it about my books that’s actually resonating with the readers here because that’s my audience and that’s the audience I want to build from.

You were talking about how you had to, as part of the Substack program, you had to post create something like a hundred newsletter in the first 52 weeks or whatever. And so, as part of that, you had to make a bunch of posts you probably wouldn’t normally make. And the interesting thing is, I feel like your newsletter 1.0, that seemed to do significantly better in terms of reaching people. At least virally speaking, it spread easier, in part because it was self-directed and because it was you sharing your thoughts. That’s an underrated part about any newsletter really. I love Chip Zdarsky’s newsletter. It feels like the character that is Chip running an email newsletter. I read yours. When you write about stuff and your thoughts on life or the industry or all these different things…

James: It’s my LiveJournal.

Yeah. My favorite post you ever did was years ago. I don’t even remember when it was. You were talking about you’re guiding principles for writing Batman, and you were talking about how you were learning from manga. There were these very specific governing principles to creation. And I think it’s interesting because sometimes newsletters can be mechanisms that are designed for sales, but I feel like it’s easier for me to buy when I kind of understand the person, if that makes sense.

James: 100%. The issue is that it’s so hard to sustain that. And part of it is just like I work on way the fuck too many books.

You’re always writing.

James: I’m always writing. It was also easier in the peak years of the pandemic when I was stuck indoors all the time, and I wasn’t socializing. I wasn’t having a life outside of my work life. I knew I needed to put my head down and sell these books. So, I did. But now I’m trying to find a new balance here because I do need to message things a little better than I have been. But I don’t have the capacity to do it myself, which means I need to bring in help.

But I know that the cornerstone of my connection to my readership is the blunt undiluted James of it all. And in order to more consistently message this stuff, I’m not going to be able to do that every single post just because I can’t. I can get out one newsletter a month right now regularly, but honestly, this was part of the reason I wanted to do this interview series. I knew I wasn’t getting at the same level of things when I would just write a little personal essay about what I thought about the industry. But I’m still interested in all those things, and I want to be prompted to deliver them.

So, it was just like, alright, I want to reach out to somebody I trust who’s going to help me on a regular basis talk about what I think does and doesn’t work in the industry. So, this has been a valuable tool in letting me continue to put that very personal voice out there in depth and in a big way, but without having to literally sit down and write multiple newsletters or write a 25-page Word document newsletter, which is also a little insane.

I know that that was part of its charm but here’s the other real thing, is I would say my readership was maybe one tenth of what it is right now. At that point, in those early days, yes, people would take little bits and pieces of it and they would spread them. There were more Bleeding Cool articles that were made out of my early newsletter posts and stuff like that, especially when I was still talking about Batman. But my readership now is much higher, and at the same time, that readership, I have the reading metrics.

The people are opening the emails and reading them. The central value of the newsletter is putting the information of what I am trying to sell to the people and in front of the people I’m trying to sell it to. The added benefit is if I say something smart about something that I think about a thing or say something in earnest about something I feel about it.

I’m just here for the gym selfies.

James: Thank you. (laughs)

To close, the calendar is about to turn to 2024, and it’s clear that you’re reassessing how you’re doing things on social and beyond. There’s a lot more video. You’re a lot more present in your posts, particularly on Instagram, and you’re doing that for yourself. That’s part of your journey in that. But at the same time, you’re out there, you’re putting yourself out there. And you even had one of your newsletters come from a guest writer this week in Jazzlyn Stone. Going into 2024, do you feel like you’re reassessing things and thinking of what the next version of all this looks like for you?

James: Absolutely. The next year is going to be a very fascinating building year for me. And I think some of that building’s going to happen out in the open, and some of that’s going to happen in secret. I mean, every year is a building year, but this next year is going to be a significant one. And it’s also one of those things that lines up pretty perfectly with where I am.

This year I had lots of launches. The last batch of my Substack grant books started coming out in print. I had the launch of w0rldtr33. I have the launch of The Deviant and Dracula. Next year it’s going to be books coming back. Department of Truth will come back. Maybe a couple of my other titles will come back. And it’s the five-year anniversary of Something is Killing the Children and my 10-year anniversary at BOOM! So comic shops are going to be well fed with James Tynion books.

But I’m not going to have a launch on the same level as a w0rldtr33 or The Deviant because bluntly, I have to finish some of these damn books. (laughs) The one exception is the first of my DSTLRY books will come out in Spectregraph. So that I will put the full force of God behind selling. But it means that over the next year I’m going to be testing things out. I’m going to be seeing what works. And something that has always been a central principle for me when it comes to sales and outreach and marketing and all of this is I want to lean into what works. So over the last year, I’ve been noticing what is working for me and what isn’t. So, you are going to start seeing me lean into things that I have noticed are working.

The greatest benefit of my high output as a creator is that I’ve created this incredible community of creators around me who I work with on a bunch of different titles. Those are the people that I sort of see as the Tiny Onion creators. And I am making steps to lean in to those elements. I want people to see when I had the Christopher Chaos team out for the launch, like me taking them to my boxing gym. It’s little things like that, a little slice of life stuff, but it shows that it’s just the relationships that we’re building while making these books, they make the books better. And that community element is tremendous.

So, I want to lean more into that community. I want to capture more of the essence of that community and communicate that community to a larger audience because of what we’re talking about. It’s an era of walled gardens. I have the opportunity to make a fairly large walled garden where I don’t have to be the only gardener. I want to do that well and I want to do that responsibly and in a way that can create the sorts of ladders up that I feel used to exist within the more mainstream channels of the comics industry.

Thanks for reading this interview with James Tynion IV. If you enjoyed this conversation, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more interviews and features like it.