On the Power and Potency of Crowdfunding, Both Today and Tomorrow

Self-publishing has always been a crucial part of the comic book game, a manifestation of the medium’s deeply DIY nature and, in some ways, the beating heart of what makes it such an attractive one to storytellers. Comics are capable of almost anything, with one of the primary limits being your imagination, something creators rarely lack in. Beyond that, the foundations of becoming a comic creator are incredibly simple: if you want to make comics, all you have to do is make comics. Then, you’re a comic creator, and you just build from there.

The problem with that, of course, isn’t on the creative side. It’s at the juncture where the creative and commerce meet. For a long time, self-publishing meant going to events or conventions or desperately trying to connect with a distributor to get yourself out there. That can be tough sledding, as it requires a whole lot of effort, connections and money. Webcomics as a whole improved this process, if only because it made publishing and building an audience far easier than before. But even then, monetizing at scale was difficult. Maybe that’s why it has always been easy to point out the successes in self-publishing, like the usually touted giants of Eastman & Laird’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Jeff Smith’s Bone, Terry Moore’s efforts at Abstract Studios, and titles of that sort.

The tense there is important, though, as that was the past. Now? The game has changed, and much of it is because of one simple phrase: crowdfunding.

“In the past ten to twelve years, it has become way easier to create things on a small scale (such as a high-quality comic or graphic novel) and sell them online, due to availability and decreased cost of digital tools, print-on-demand technology, and a strong e-commerce ecosystem,” said Margot Atwell, the Head of Publishing at Kickstarter. “Kickstarter and other crowdfunding platforms help creators to connect with their fans and find new ones, and generate the necessary funds to pay collaborators such as artists, editors, and printers.”

That’s led to a massive shift in how self-publishing works, and a blurring of the lines between the way creators create and fund their projects.

“I mean, they’re really one and the same,” Check, Please! cartoonist Ngozi Ukazu said about crowdfunding and self-publishing. “I would say that self-publishing is probably 99.9% funded by crowdfunding nowadays, whereas maybe before Kickstarter and Patreon, people would self-publish and try to make back their expenses at a zine fest or at a convention.”

Platforms like Kickstarter, Indiegogo, Patreon and others have helped create a financial infrastructure for those who want to do their own thing, and in many ways, it has revolutionized comics. It’s a way for creators and stories of all types to find their audiences, for storytellers to gain some level of control to their fates, and for fans and their faves to help each other out in a direct way. There’s immense power to that.

And in a time of great uncertainty – like one in which a global pandemic leads to an economic crisis – there needs to be, as these platforms could become even more important than before. That’s why it feels like the right time to take a look at the overall crowdfunding landscape – particularly on the project-oriented side with Kickstarter and Indiegogo – and to examine not just where they are, how they got there, and what creators have learned from them, but what place they might have going forward in the broader world of comics.

This all begins with the only place it can: Kickstarter, the clear-cut number one in the project-based crowdfunding comics market. It’s a position the platform has held for as long as it has existed seemingly, and it’s coming off consecutive years of record highs both in terms of dollars generated – over $16.2 million in 2019 – and projects funded, with 1,597 last year. Those are obviously big numbers, but to contextualize that a little bit, its revenue number would have made Kickstarter the fourth biggest publisher in the direct market and the seventh biggest in the book market. That’s pretty significant.

That success has stemmed from buy-in amongst creators and consumers, as Kickstarter thrives both from a depth of backers standpoint and a success rate one, Atwell shared with me.

“More than 800,000 people have backed at least one comics project on Kickstarter, and almost 150,000 have backed three or more. The success rate in the category is extremely high: since the beginning of 2018, it has averaged 69-70%,” Atwell said. “To me, this means that comic fans like what they find on Kickstarter, and comic creators have a great shot at funding their work on the platform.”

A crucial aspect of Kickstarter reaching those numbers has been its focus on building up comics as a channel. As Atwell told me, “Comics are an important and growing category on Kickstarter,” and much of that came from its two leads. Until recently, Kickstarter had a comics outreach lead in the esteemed Camilla Zhang – whose departure came amidst pandemic related layoffs at the company – and continues to have an advocate in Atwell, who views the platform as a strong alternative to traditional channels, particularly for marginalized creators.

“One thing I love about Kickstarter Comics is that the platform helps creators find support and enthusiasm for stories that often have not been embraced by Big Two comics publishers and other mainstream outlets,” Atwell shared. “Comics created by and centering (on) people of color, LGBTQ+ folks, and people with disabilities raise money and find excited audiences on Kickstarter.”

Part of this derives from Kickstarter’s nature as a Public Benefit Corporation, a type of for-profit company that’s “obligated to consider the impact of their decisions on society, not only shareholders.” The crowdfunding giant has policies built off those ideals baked into its very core, making it a welcoming space for creators of all varieties and ensuring a racial, gender and orientation makeup far different from what you’d see at most publishers.

“We have a strong policy against hate speech and abuse, which we enforce,” Atwell told me. “That honestly should be par for the course on every online platform, but there are a lot of places online where women, PoC, LGBTQ+ folks, and other people from marginalized communities experience a lot of harassment.

“That’s unacceptable, and on Kickstarter, we don’t tolerate it. Having a sense of safety online can make it a lot easier to do great work.”

Being welcoming to more diverse creators results in far more diverse work, it turns out, with Atwell citing a trio of examples as evidence in Kwanza Osajyefo’s BLACK, Taneka Stotts’ Eisner-winning Elements: Fire anthology, and We’re Still Here, an anthology centering on “trans stories told by trans creators.” That’s the tip of the iceberg, and underlines one of the foundational strengths of the platform.

“Stories like these finding a passionate readership is why Kickstarter exists,” Atwell said. “I have strived to make Kickstarter a place where everyone can see themselves reflected in stories, and where people telling stories that haven’t been heard yet can find readers who are thrilled to read them.”

Its welcoming nature is only one aspect of its appeal. The Beat’s Heidi MacDonald cited its leadership as a huge advantage, but also its relative predictability for creators who have leveraged the platform for a while now.

“The system has been finetuned and it’s pretty reliable up to now,” MacDonald told me. “Creators can get predictable results, and there’s a lot of infrastructure to back it up.”

That’s important, but it wasn’t always the case. Kickstarter itself was only founded in April of 2009, so once upon a time, it was a complete unknown. Creators needed to take those first steps with it to prove its value. It had someone to do that in Iron Circus Comics’ C. Spike Trotman, who has created – and funded! – 26 projects on the platform since its launch, making her one of the great examples in comics of the platform’s potency. Her decision to go with Kickstarter was easy: it was the only game in town when she started.

“Honestly, I chose Kickstarter because it was the only option!” Trotman said, noting that “crowdfunding” wasn’t even a word at the time. “I started launching projects on the platform in 2009 because it was just an evolution of what a lot of webcomic people were doing already; self-funding projects from fanbase donations and pre-orders.

“Kickstarter was better than our Paypal tip jars because it was transparent and automated; it meant less work for us and more visibility for our work.”

The interesting thing about those early days was how it was perceived as “essentially begging” amongst creators and skeptics, Trotman shared. Much has changed since then, as that stigma disappeared when crowdfunding was embraced by creators of all varieties. Even those early skeptics have jumped onboard, with Trotman adding she “can’t think of a single Never-Kickstarter type who hasn’t launched a project by now.

“Funny how that works.”

Others I spoke to signed up for a multitude of reasons. Cartoonist Kyle Starks told me that it just came down to Kickstarter being the only viable way to fund the kinds of comics he wanted people to read, especially if traditional publishers weren’t an option. Veteran cartoonist Ron Randall was publishing his creator-owned series Trekker as a webcomic, and when the print version’s publisher – Dark Horse – no longer fit his goals, he considered his options and found Kickstarter to be the most appealing one.

“I had no idea what sort of support I’d receive,” Randall said. “So, I held my breath and hit the launch button.

“It funded in a day and a half and I haven’t looked back since.”

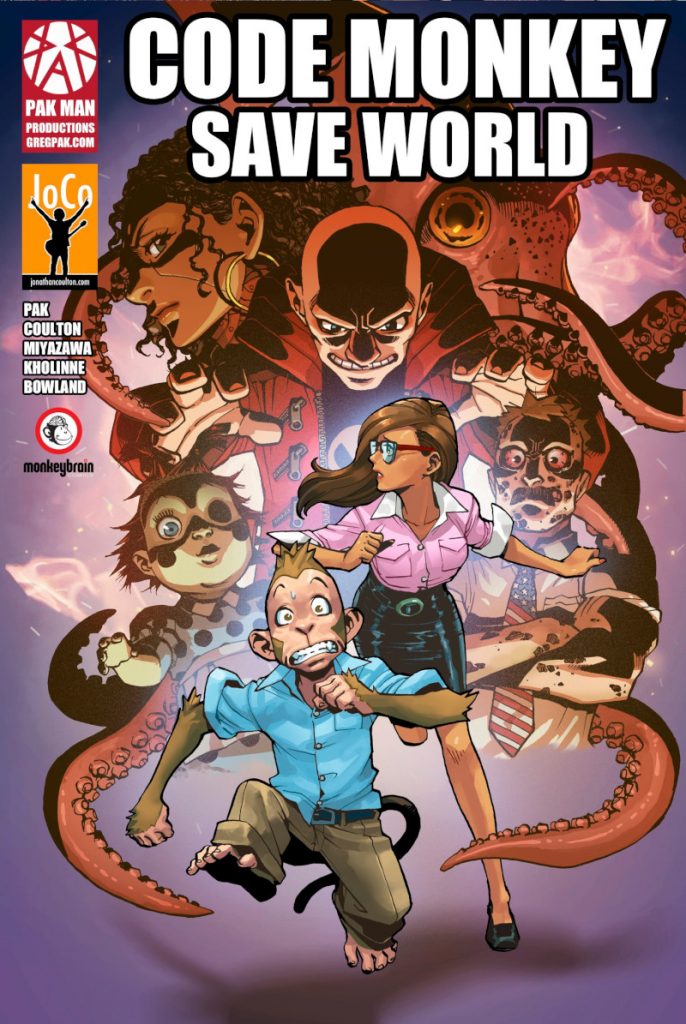

For Greg Pak and his collaborators on the 2012 graphic novel Code Monkey Save World, their decision to go with Kickstarter came down to two main elements: name recognition and the platform’s all-or-nothing funding model.

“This was in 2012, when (crowdfunding) was still relatively new for a lot of people, so going with a site with the most legitimacy felt like a key part of getting everyday people comfortable with backing,” Pak told me, before adding about the all-or-nothing model, “That felt just right — we didn’t want to get into a situation where we received half of the money we needed for the project, because then we’d be on the hook for something we couldn’t deliver without going bankrupt.

“Better to get nothing and try again later after making any necessary adjustments.”

Every creator I spoke to has had excellent experiences, with the exceptions largely coming from unforeseen issues, like Starks and his struggle to fulfill certain elements of his recent Old Head Kickstarter when vendors dried up during the pandemic. For the most part, coming back for more with Kickstarter is an easy sell. Starks loves the personal interactions with fans, and maybe most importantly, the creative freedom.

“I like to do what I want how I want without a lot of notes or suggestion,” Starks said.

Randall loves the creative control as well, as it gives him the chance to deliver the book in his preferred format and at the frequency that allows for the most reader and creator satisfaction, even if it is a lot of work.

“I’ve never been more satisfied in my career,” Randall said. “I’ve also never been busier. I’ve had to take on the hats of publisher, marketing department, and distributer on top of the only jobs I really want to do—writing and drawing the stories.

“But it’s absolutely worth it to have the book’s completely in my own hands and those of the readers.”

Trotman shared two main reasons she continues to leverage Kickstarter, saying it ensures her projects go to print already in the black and that it gives her space for experimentation, allowing her to view where consumer demand might be for new ideas. She believes this platform is the “primary reason” Iron Circus Comics “has been able to grow at the speed it has.”

“For the foreseeable future, I don’t see any reason to not use Kickstarter, when the situation merits it; I’ve built a strong audience that likes what I put out,” Trotman said. “Every time I launch a new project, 25,000 previous backers get an email about it. That’s a phenomenal advantage!”

Pak emphasizes its name recognition and highlighted Kickstarter employees forming a union 1 as attributes that continue to appeal to him, but Trotman’s last point was one of the most powerful ones for him as well. It’s easier to succeed with a project if you start with a strong base.

“It’s where our backers know to find us. Once you do a project, you get a mailing list of all the people who backed you,” Pak said. “So now when we launch a new project, we can send an update to everyone who backed us before, and they can click one button and back the new project. Switching to a different platform would make that less seamless, and with everything online, you want to be as seamless as possible.”

That’s the fascinating thing about Kickstarter. To a degree, success begets success. By showing that you can fund and fulfill one project, you have proven yourself for later efforts as well. 2 Kickstarter makes it easy for creators to capitalize on that, and that’s a crucial element of why both creators and consumers continue to return. And with that high hit rate of nearly 70% of projects funded, many of which put up big numbers, Kickstarter’s best advertising to creators are the comic projects that consistently perform already. While there are plenty of other benefits, it’s important to remember that consumers and other creators aren’t the only audiences for these projects either.

“A successful Kickstarter campaign can be a stepping stone to increased visibility for an artist or writer, whose ability to draw an audience is undeniable after they run a successful campaign,” Atwell noted.

Ukazu is a perfect example of that. Her webcomic Check, Please! had generated a passionate fanbase, and it was one that wanted the series in print as well. So where did Ukazu go? Kickstarter, where the cartoonist funded four projects – the first three years of her wondrous sports/romance/slice of life comic and a Chirpbook collecting the best tweets from series lead Eric Bittle – to the tune of nearly $918,000. That alone would have been cause to celebrate, but it also created an atmosphere of desirability in the project amongst publishers. While comics maven and Randon House Graphic Publishing Director 3 Gina Gagliano was onboard even before its success on Kickstarter, 4 Ukazu noted, interest skyrocketed once the title’s second campaign nearly hit $400,000 in funding.

“After that, it was Abrams, BOOM! Studios, First Second, and I think another,” Ukazu said, before adding that they “were all like, ‘okay, yeah, we would like to print this, please, now.’ I’m very thankful that the Kickstarter did well enough to garner that attention.”

While Ukazu appreciated it, she saw it for what it was: publishers recognizing opportunity.

“All these publishers, I think they are very kind and they were doing meaningful work, but for them, it was like dollar signs,” Ukazu shared. “It was like, ‘Oh, this is big, and it’s just a webcomic. We can put it in bookstores. We can put it in libraries. We can put it in schools.’”

They were right. Ukazu eventually signed with Gagliano and First Second, and its final volume at the publisher became a New York Times best seller. That’s the thing some forget about crowdfunding. It’s part of a process, and if you see a lot of success with it, it could lead to even more. All of this is why Kickstarter has seen the continued growth it has in comics: it raises both the floor and the ceiling for projects that might not even exist otherwise. That’s powerful.

The other key pillar in the project-based crowdfunding world for comics is Indiegogo, the clear #2 in the channel behind Kickstarter. Now, I say “clear #2,” but it’s worth noting that this is just based off of broader sentiment, analysis of available statistics, and conversations with people in the industry. Unlike Kickstarter, Indiegogo isn’t very transparent with performance metrics on a channel-by-channel basis – Kickstarter releases yearly reports on performance for comics, while the only numbers I could find for Indiegogo are for the totality of the platform – and they never responded to inquiries for this piece. But there’s little doubt that they’re the second fiddle in the market, even if there is a lot of value in the platform.

Of course, this begs a question: what made Kickstarter the leader in comics over Indiegogo? There are a lot of theories, but the most likely one is the typical answer for these kinds of splits: it’s where the content went to start, which made others want to follow.

“By (2015), 5 most of the most popular webcomics crowdfunding campaigns had taken place on Kickstarter,” Ukazu said. “So I was following the footsteps of other smaller webcomics.”

“It was just kind of the precedent set by other projects and other creators.”

To a degree, it was almost a self-fulfilling prophecy. Early comic projects thrived on Kickstarter, which attracted more creators, each of whom was learning from the campaigns that preceded them. Again, it had a “success begets success” like flow, generating brand awareness and belief in the structure at Kickstarter. Meanwhile, Indiegogo didn’t have the same proof of concept in the channel, with the platform seemingly operating under an “if you build it, they will come” mentality, taking whatever they could get when it came their way without a showstopper project to tout in the channel. Once Kickstarter took ownership of the space, it almost seemed like Indiegogo viewed comics as a secondary channel, especially given the limited funding ceiling within that category compared to others like tech and film.

That’s not to say Indiegogo doesn’t have its advantages. Its website is arguably slicker, it offers a bit more campaign support seemingly, projects that fund all the way are given access to the platform’s InDemand functionality to extend the reach and impact of the project, 6 and most importantly for some, projects on Indiegogo can operate under a flexible funding strategy where you do not have to reach your goal to give your team money to build off of. 7 That can be a pro or a con, depending on who you are, as the creators I spoke to were mixed on the prospects of that last idea. There are considerable strengths to the platform, and ones that could make it appealing to any creator.

Regardless of any advantages it may have, it seems that in comics, Kickstarter dwarfs Indiegogo by almost any metric. One particularly concerning statistic is the depth of backers on each. While Kickstarter has over 800,000 unique backers in the comics channel, per Atwell, a tour of the top performing Indiegogo projects suggests considerably less reach. That may be because unlike Kickstarter, which thrived because of the expansive scope of creators and comics on the platform, Indiegogo’s success has largely been derived from a narrowing of its field. For many, it’s viewed as the domain of one group: Comicsgate.

What is Comicsgate, exactly? Well, you likely know already, but simply put, it’s an online harassment campaign that attempts to disguise itself as a heroic attempt to stand up for what comics are all about, and what comics are all about – at least in their mind – is seemingly anything that doesn’t involve women or diversity or change from the eternal status quo. If it fits those boxes, they attack, abuse and harass, using their talking points as almost recruitment pitches for like-minded individuals.

Now, it should come as no surprise to you that these individuals also make comics to showcase what they believe comics should be, which are often regressive, derivative ideas filled with big guns, big arms, and big…other things. 8 And they’ve produced these comics by leveraging Indiegogo as their crowdfunding platform of choice.

Why Indiegogo, you might be wondering? One clue could be found within this very text, as Atwell mentioned that Kickstarter has policies against hate speech and abuse, two core tenets of the Comicsgate way. Additionally, Kickstarter has always been vocal about how it views the world, and it’s clear it is the opposite of how Comicsgate-related individuals do. Lastly, Indiegogo likely better fits the group’s push as outsiders on the side of the right, with this unclaimed platform forming a better match for their own position. Like with Kickstarter and webcomics creators, a precedent was then effectively set for members of this group to call Indiegogo their crowdfunding home.

This relationship has generated projects with very high funding numbers, with the average earnings of the 20 most funded projects on Indiegogo – many of which are Comicsgate related 9 – being a robust $273,117. This group has no problem letting anyone and everyone know about this, either. However, when you actually dig into the numbers, it suggests that a lot of these projects aren’t funding at these levels because of a deluge of supporters. Instead, it’s because they have the power of belief behind them, with these campaigns seemingly acting as a proving ground for their buying power as a group.

“I’ve been investigating some of the huge campaigns on Indiegogo that are Comicsgate related and it really does seem that there is a pool of wealthy backers who want to support these projects as a statement against ‘forced diversity,’ whatever that is.” MacDonald told me. “I think people need to accept the fact that a lot of Indiegogo campaigns right now are basically comics Super PACs and just use the platform for their own purposes.”

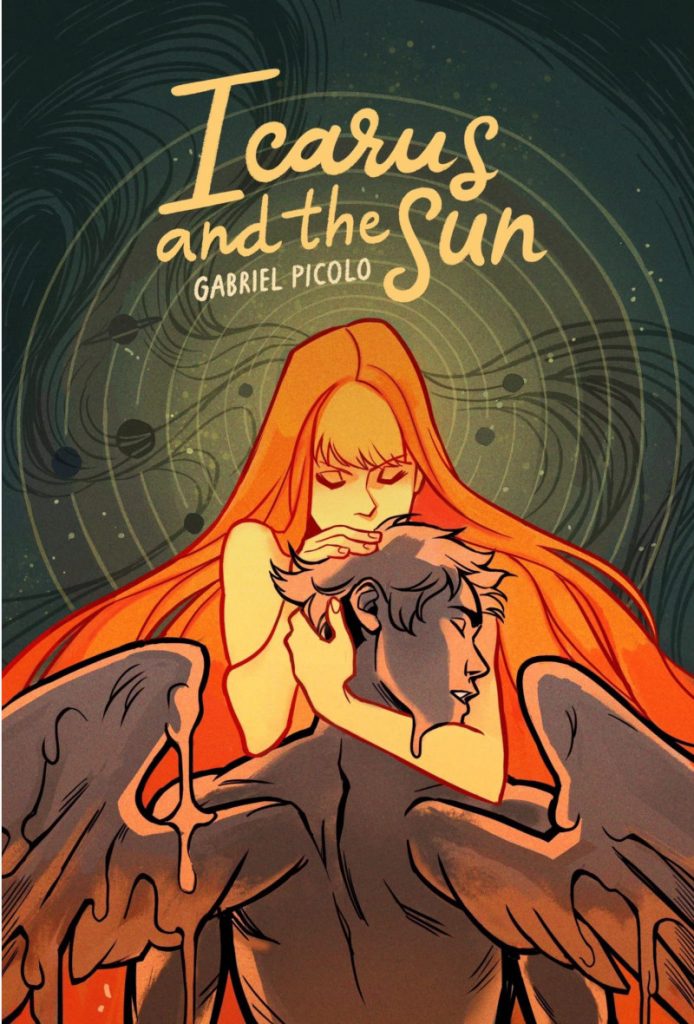

That “comics Super PAC” 10 idea is a perfect one. That’s pretty much exactly what it seems to be. But like with a Super PAC, this group is hardly a representative cross section of society, with it instead being a small selection of believers fueling them. Just look at the most funded comic projects on Indiegogo to see how that’s the case. The project with by far the most backers – nearly double the second place finisher – is Gabriel Picolo’s Icarus and the Sun, the one project with absolutely zero Comicsgate connection or endorsement. 11

In fact, when you look at the 20 most funded comic campaigns on each platform, 12 you find that Kickstarter’s top performers generate nearly 29% more backers and over 32% more funding on average. That’s where the depth comes in, and you can already see conviction waning amongst the Indiegogo faithful, to a degree, with some of the flagship works dropping off project-to-project.

Not everyone who uses Indiegogo as a platform is Comicsgate affiliated, though. That’s important to remember. Creators like Randall, Jim Starlin and Chip Mosher have used its InDemand functionality – a nice tool that allows you to keep selling additional copies of your comic if it was already funded on Indiegogo or even Kickstarter – to great success. That number could increase because awareness in the Comicsgate and Indiegogo connection isn’t universal. Ukazu expressed surprise when I mentioned it to her. She’s not alone in being unaware. For those reasons – and because of the current economic crisis – MacDonald hopes Indiegogo is still perceived as a viable platform for creators.

“I think survival is going to become the main motivation for a lot of people, and I hope that there can be some clarity between those who are using it for non-CG purposes and the CG crowd,” MacDonald said. “Critics and observers need to understand that just using Indiegogo doesn’t make you a member of Comicsgate.”

MacDonald’s points are correct, but it’s worth noting, these concerns have effectively irradiated the platform for those outside that group. I did a straw poll of creators from several parts of the industry, 13 and each of them said they wouldn’t run a campaign there because they view it as a no-fly zone due to its Comicsgate connection. One said they wouldn’t even back a project on there. That’s a problem for its long-term viability, even if it’s still a valid platform, and something that might be a better fit for the goals of certain projects.

The question from there becomes, “Does Indiegogo know about this?” Due to their lack of response, it’s impossible to say for certain. However, they’re a tech company, which tend to be all about data and emphasizing what succeeds. It’s hard to imagine they are unaware.

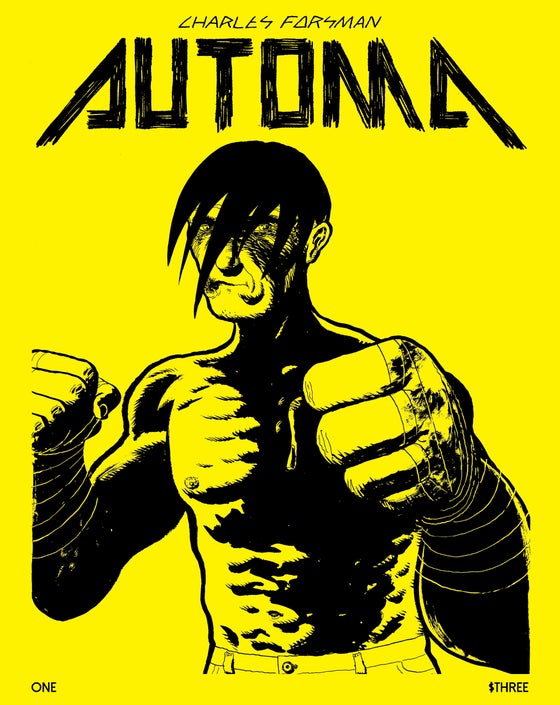

These two platforms aren’t the only crowdfunding options for creators, of course. Both Patreon and Ko-fi are heavily leveraged in comics, with the former being used in a particularly robust fashion. Creators like Lore Olympus’ Rachel Smythe have used Patreon to give that Webtoon title’s passionate fanbase a home, while others like Charles Forsman have even used it to fund and distribute comics, like AUTOMA, Forsman’s monthly print series that can only be acquired there. Many others use it for sharing behind the scenes looks at projects, personal anecdotes, work in progress shots, and much, much more, all of which helps creators generate a little (or a lot, in some cases) recurring income.

These platforms are great ways to expand potential earnings and form a foundation to build off of, but they are typically not enough to rely on as a primary source of income. Realistically, they’re more support elements than anything, with project-based crowdfunding options like Kickstarter and Indiegogo acting as primaries for those who choose to explore this route.

And it’s worth mentioning that crowdfunding isn’t necessarily for everyone. There’s obviously a ton of upside – all you have to do to see that is to look at the six figure numbers some projects generate – but with that comes downside as well. Much of that can come from the same place, and that’s the reduced distance between fans and creators.

Sometimes that downside manifests in what Trotman described as a “parasocial relationship,” where “someone invests a lot of time and emotional energy” into a creator who isn’t aware of who they are, and an inequity forms between the two views of that connection. Trotman said “it can get pretty uncomfortable.”

Ukazu said that can also show itself as people becoming “almost too demanding,” where readers can “verge on entitlement” about how they feel about a comic they’re invested in. But for the most part, Ukazu believes that’s rare.

“The majority of readers and audience members are consuming, and they’re consuming very happily.”

A lot of the downside related to that creator/fan connection falls on the former, though. We’ve all been there, probably. You back a project by a favorite creator and you never see the comic come to life. That can permanently affect how you feel both about that creator and crowdfunding itself. That’s why it’s incredibly important to do your homework before jumping in. Ukazu estimates that 80% of the work in crowdfunding comes during the fulfillment phase alone.

“It’s so hard to fulfill a Kickstarter. There’s so many unknowns that you only discover once you’re in the thick of it, once you’re in fulfilling, once it’s one AM and you’re in an Excel sheet and you’re trying to differentiate between domestic and international shipping,” Ukazu said. “You really have to know this isn’t just free money you’re playing with. People are investing in you.”

“If you don’t take that seriously, oh my goodness, it will come to get you.”

When that happens, it can have an area of effect that’s harmful to all creators. As Starks mentioned, the first year or so of comics on Kickstarter generated huge funding, “but so many people failed to come through and sort of poisoned the well.” That’s why those I spoke to said that for crowdfunding to continue to grow, creators have to behave responsibly.

“We, the creators, need to keep our promises to our backers, and deliver them unique and good quality stories in a timely fashion,” Randall said. “If a creator isn’t prepared to do that, they should wait until they are before hitting that ‘launch’ button on their campaign.”

Ukazu recommends starting small, as it’s a good way to prove that you not only can make something, but deliver on it. This does two things: you figure out if you actually enjoy the process, but it also helps build your audience and faith in your ability to deliver.

There’s upside too. Having a potential ceiling of six-digit earnings on a project you own is a life-changing thing. 14 If you succeed, there’s increased potential of repeated success. There’s unbeatable amounts of creative freedom, because it’s all you, all the time. It also invests fans in the process, as they can feel good about helping bring something to life. As Starks said, “I think knowing you have a direct hand in something being created is really gratifying.”

“I think those little interactions with the creator, the little extras – it’s a more rewarding experience than just taking something off a shelf.”

But ultimately, it’s not for everyone. As Pak told me, “the whole crowdfunding experience is…a lot.”

“Crowdfunding requires creators not just to make their work, but to handle publicity and public relations, project management, contracting and scheduling, budgeting and accounting, delivery, and customer service — and to take on all of the risks involved if something goes wrong,” Pak shared. “I happen to be wired in such a way that I actually enjoy most of those different aspects of the process. But crowdfunding a comic book takes an exponentially larger amount of time than just writing a comic book, for example.

“I’ve concluded that the rewards make it absolutely more than worth it, but every creator’s results may vary.”

That can lead to an experience that’s mentally, emotionally, and even physically stressful. 15 Because of that struggle, companies and services have been created to help mitigate some of the aspects of this work that’s less comfortable for some. There are a slew of comic marketers out there to help with promotion, and fulfillment houses like White Squirrel and DFTBA can assist with ensuring your project is properly distributed upon completion. There are ways around even the tougher aspects of the crowdfunding process. They’re not for everyone, but solutions are there for those who are less confident on that side of the experience.

It’s clear that there are plenty of options for creators who want to make the comics they want to make the way they want to make them. Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and to a lesser degree, Patreon and Ko-fi have helped those in the self-publishing game succeed and, on occasion, thrive. As Trotman said, Kickstarter is “practically an expected milestone in the careers of modern comic creators.” MacDonald agreed, describing it as a “pretty huge part of the indie comics scene, not only on its own but as a feeder system to book publishing.” 16 Crowdfunding isn’t just part of the future of comics; it’s a core component of the present.

And in the face of the pandemic, where many publishers went pencils down with creators who were reliant on that work, it may become even more important. While the influx of creators who have used these platforms during this experience likely had more to do with pre-pandemic decisions than current ones, 17 I’ve had plenty of conversations where crowdfunding was being considered more heavily than ever before.

Atwell shared that “in spite of the pandemic, (Kickstarter has) seen that comic backers are still showing up for projects at this time,” noting that two of the ten most funded comic projects of all time on Kickstarter ended in the past couple months. Interest hasn’t waned in the face of the coronavirus.

There are still concerns for those interested in using crowdfunding in this environment. There’s the pandemic-related economic crisis, which will have a tremendous impact on available funds for any consumer. Pak and others are worried about the Trump administration’s attempts to “undermine the reliability and financial security of the United States Postal Service,” as that service’s affordable shipping rates are essential to profitable crowdfunding campaigns. 18 Lastly, it’s already difficult to promote and advertise your campaign, but in the current situation, garnering visibility will be an even greater struggle with funding limitations.

Those are all real concerns. But beyond even the broader societal issues we’re facing, there is one looming problem with crowdfunding itself. To a degree, this strategy has become one that isn’t quite as new creator friendly as it once was. As Ukazu told me, “I think that, unfortunately, there are a lot of barriers to entry to even doing a successful Kickstarter.”

“Some of those barriers include you have to have a platform already, which some people can achieve, which is great. But if you aren’t able to build a platform, then you won’t be able to get a large readership or a large audience on Kickstarter.”

Trotman shared that “a good Kickstarter prospect features a creator with a pre-existing online audience; one with a mailing list, who’s active on social media, who posts work frequently and talks to fans. Someone who’ll participate in any promo we line up, like interviews or podcast appearances. It helps a lot if they have natural charisma, too, which is unfair to the wallflowers of the world, but nevertheless true.”

And that’s a lot. Not everyone has that. That’s why many of crowdfunding’s biggest successes have spun out of already popular webcomics and, more recently, comics that are successful on platforms like Webtoon. That’s part of the reason Webtoon is such an interesting platform, 19 as it’s easy to retrofit it with crowdfunding options like what Smythe has done on Patreon and Mongie did on Kickstarter. It’s a snug fit, with these platforms complementing each other nicely. Having that built-in fanbase is critical to success, making the crowdfunding game not entirely dissimilar to regular old creator-owned comics. Simply having a good comic only gets you so far.

“You could be the author of a masterpiece, a world-rocking book that will change the course of publishing, but if you won’t promo your campaign, that won’t mean much to the bottom line,” Trotman said.

But even with those concerns, crowdfunding is undeniably a huge part of comics today. Even Indiegogo might play an important role, if it can overcome the stigma associated with it. 20 Crowdfunding with that platform or Kickstarter is a bet on yourself instead of relying on others, a good direction if you can swing it. Pak believes it has value because freelancers lack control of “if or when people hire” them, “so it’s hugely important to have ways to produce and distribute that aren’t depending on any one company.

“Crowdfunding is (a) big piece of that healthy balanced breakfast.”

Is crowdfunding a big part of the future in comics? Could it take a larger role? Can it be broadly viable for comic creators? Your answers likely depend on who you are. But for Trotman – someone with as much crowdfunding comics experience as anyone – the answer is “yes” across the board.

“I think we’re far from the ceiling on what Kickstarter can do for cartoonists/comic creators, because supporting a cartoonist on Kickstarter is about being a fan more than anything else,” Trotman said. “There’s not some big pool of money we all draw from, and then when it’s empty, we hit a wall and there’s no more room for anyone new. Each creator/project creator brings their own personal fanbase to the site. Sometimes there’s crossover between projects, sometimes not.”

“But the main point is, the only limit on what Kickstarter can do for creators, in my opinion? The kind of creators who use it, and what they use it for. It’s a fantastic platform, literally life-changing.”

That’s the beauty in crowdfunding. It opens the doors for so many different types of creators and stories. Randall, a 63-year-old cartoonist, isn’t likely what people envision when they think of those embracing crowdfunding. But he’s been energized by the experience, especially with the “diversity in new creative faces and voices” emerging because of it, adding something special to the existing infrastructures within comics in the process.

“I see new creators on crowdfunded projects that are already energizing and breathing fresh life into comics. They aren’t going anywhere. And it feels like their numbers are growing,” Randall said. “At the same time, there are those who still love the more familiar model of creating and experiencing comics. I think we’re a pretty big tent.

“I think there’s room for us all.”

Thanks to Atwell, MacDonald, Pak, Randall, Starks, Trotman, Ukazu, and everyone else who spoke to me for this piece. If you enjoyed this feature, consider supporting future pieces like this by subscribing to SKTCHD.

This was a very controversial time in Kickstarter’s history, as Pak noted, saying, “I’d been concerned about the platform during the controversy during the fight for the union, but I’m glad there’s been a positive outcome.”↩

More on this later.↩

And then-Marketing and Publicity Manager at First Second.↩

Ukazu recounted an experience at a con where Gagliano came to her table and said, “I would like to buy Check, Please!” to which the cartoonist responded, “Ma’am, you have to go to the end of the line. Who are you?” She discovered Gagliano wasn’t a random fan and someone who wanted to buy it in a different way, and the rest is history.↩

When she launched the first Check, Please! Kickstarter.↩

More on that in a bit.↩

You can also use fixed funding, which is the same, “you only get your money if you’re fully funded” method Kickstarter uses.↩

It all feels very 1990s.↩

Trying to find a creator to chat with me for this piece who uses Indiegogo without any semblance of a connection – by endorsement, relationship or straight collaboration – was honestly surprisingly difficult, at least amongst those at the top.↩

For those that don’t know, a Super PAC is basically a political committee used to generate funding for individuals or causes.↩

Quick note: Other projects in that group aren’t directly affiliated with Comicsgate, like Sean Murphy’s The Plot Holes. But there is certainly smoke perceived around some of these projects by the general populace even if there isn’t fire.↩

As a note, I pulled some of the Kickstarter comic projects that weren’t really comics from the mix and replaced them with comics. If I included all of them, the gap would be even bigger. Also, I removed anomalous fits like Icarus and the Sun from the mix as well. Lastly, I kept this to strictly the project side of things – no InDemand sales are included.↩

None of whom were quoted for this piece.↩

Even if it’s important to remember that a lot of that money will go to fees, taxes and production.↩

If you doubt the latter, talk to any creator who had a hugely successful comics Kickstarter about how many boxes you have to deal with!↩

MacDonald used Check, Please!, Trotman’s Iron Circus Comics, and cartoonist Ben Passmore as three examples of success stories in that regard.↩

I saw people suggesting something like Jeff Lemire, Matt Kindt, and David Rubin’s Cosmic Detective was a reaction to the pandemic, but these kinds of projects require a ton of advance work. We’re likely just starting to see the reactions to the pandemic come to life in crowdfunding.↩

Pak advocated for fans to reach out to their representatives to support the USPS, especially if they care about the viability of creators doing things their own way via crowdfunding.↩

For more on it, you may enjoy my previous feature on its rise.↩

The InDemand functionality alone is worth a long look by any creator who crowdfunds without intent to publish elsewhere.↩