Do Events and Crossovers Help or Harm Tie-In Titles?

X of Swords is an interesting test case for the impact of larger, multi-title stories. But does the past suggest it will make or break the X-Men line?

X of Swords, the inaugural Jonathan Hickman-era X-Men event, is coming soon, and people are excited. A story fronted by Hickman and Tini Howard! Interconnectivity! SWORDS! What’s not to like? Unfortunately, we discovered something for people to dislike, as this crossover was recently revealed to be 24 chapters long. 1 This was met with a fairly mixed response. Some are excited about a big, gigantic story in the vein of Messiah Complex or Second Coming, and others are unenthusiastic about the idea of buying 24 comics from nine titles and several connected one-shots that range in price from $3.99 to $6.99. It would be understandably polarizing if the world was in a usual state, but we are hardly there right now. When you pair the largesse of the X-Office with a pandemic and resulting economic crisis, well…it’s even more so.

When I wrote about this revelation in my weekly column, Comics Disassembled, I made an atypically cavalier assertion when I said the following:

This type of decision making is considered to be a “rising tide lifts all ships” move, but I believe it makes it harder for lines to thrive, as I feel like these stories are jumping off points as much as they are jumping on ones.

After I published that, klaxons went off in my brain as I realized how against my broader approach to the world this suggestion was. “Is that true?” my brain wondered to itself. “Do we have evidence that an event or crossover can negatively impact individual titles by forcing them into larger, connected stories?” I had no idea. That was a problem for me, as not knowing things is generally my enemy. 2 The good news is a solution was reasonably easy to find. All it took was a whole lot of exploration of data, selecting a broad set of events and crossovers from recent history to figure out how titles that tie in are affected. So I did just that, in hopes of answering whether or not this interconnectivity helps or harms individual books. I ended up finding out a whole lot of other things in the process, which we’ll be examining beat by beat today.

So you know what that means everyone: it’s time for a chart party!

Before we get into the specifics, I wanted to talk about my process. It’s important you know going in what was looked at and how I did what I did.

First off, all numbers come from Comichron and are then adapted into Excel spreadsheets by yours truly. John Jackson Miller’s site remains undefeated, an absolutely critical site to the understanding of how the direct market works. Key to understanding that site: these aren’t “sales” but orders from comic shops. Remember that.

Second, I focused primarily on larger events and crossovers, at least in the vicinity of X of Swords levels of importance. I didn’t go back any further than 2008, as any further back would have pushed us into dramatically different market environments. That meant the included events and crossovers included:

- Final Crisis

- X-Men: Messiah Complex

- Blackest Night

- X-Men: Second Coming

- Siege

- Forever Evil

- Civil War II

- Secret Empire

- Dark Nights: Metal

- War of the Realms 3

Once titles were selected, I went back and tracked sales for issues before the event for historical context, then cataloged tie-in performance, before concluding with at least three or four issues worth of sales data after the event concluded to ensure shops were able to reflect a decrease or increase of reader interest in orders. Standard attrition suggests orders would drop anyways, but I wanted to explore a little further out to see if it became more than that. Everything was then compared to the pre-event orders to give us percentage change numbers.

Third, I didn’t examine every single tie-in for every single event or crossover, because some of these events involved basically the entire line. I focused on getting a collection of high, medium and low level titles, providing an appropriate balance to what was factored in. 4

Lastly, all of this data is very noisy, making it not necessarily predictive, for reasons we’ll get to. That’s important to keep in mind. As I discovered while putting this project together, Marvel and DC get really weird and eager to change coming out of events. So a huge portion of the titles I tracked ended up getting canceled or relaunched out of the crossover they tied into. Sometimes titles were even renamed (i.e. X-Men became X-Men Legacy after Messiah Complex), sometimes events lead into other events (i.e. Venom going from War of the Realms to Absolute Carnage), and often, creative teams changed after the story completed. All of that can have an impact on orders, so that’s important to remember when you’re attempting to make strong assertions from the data.

Enough preamble, though. To the fun stuff!

So let’s start with the big one: was my theory correct? Does it seem like being forced to tie in to an event is a jumping off point as much as it is a place to onboard new readers?

Not necessarily.

It depends.

Sort of.

Let’s look at a chart.

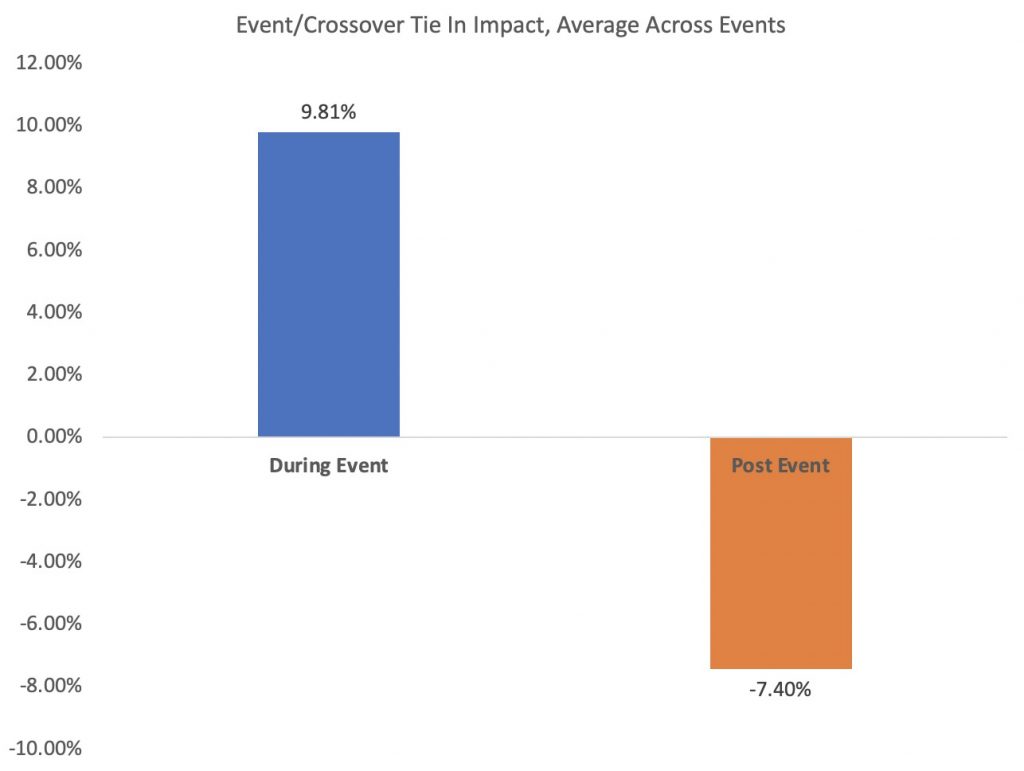

This chart shows how orders changed for the tie-in titles during the events I tracked on average, and from there, how they changed after that story concluded. Again, both of those percentages are relative to where orders were before the titles tied in to an event or crossover. So this shows us, quite simply, that the average event tie in saw a lift of 9.81% versus preceding issues. Given that this is working against standard attrition, you could argue that the number really is a little bit higher, but still, a nearly 10% lift is nothing to sneeze at. No wonder Marvel and DC love to tether every title they publish to these gigantic crossovers.

Beyond that, there isn’t that significant of a downturn after the event ends. On average, titles see a dip of 7.4% from where they were before an event, and given that most of the titles I examined tied in for two or three issues – a pretty decent chunk, especially in the modern era – that’s probably what standard attrition would have looked like anyways, roughly speaking.

So an increase of nearly ten percent and a downturn of just over seven? You know what that means, right? It’s simple. We have our answer: events are a jumping on point for titles that tie into them!

Okay, maybe it isn’t quite that simple.

It turns out getting 12 years of data can lead to some interesting trends being discovered, and beyond that, this is a broad data set in terms of results. Consider this: the highest increases in sales during an event were 58.2% – that belonged to issues connected to Metal – and Blackest Night, which saw a lift of 58.08% without even including the highest ordered tie-ins because they also led to shops getting physical rings along the varying Lantern spectrum. If I included those issues, the lift rises to nearly 77%, but it felt too much like cheating to me. That’s quite the boost, but that kind of jump is hardly guaranteed. Both Civil War II and Forever Evil 5 actually saw double digit decreases on orders during the event, seemingly reflecting the lack of faith shops had in both the events and related titles.

On the flip side, those same two titles – Civil War II and Forever Evil – saw tie-in comics decrease in sales by over 18% once they returned to regular scheduled programming, with even a flagship book like the Geoff Johns-written, New 52 era Justice League title getting nuked, post event. Matching the outlandishness of that idea, two events actually drove gains for their tie-ins on average after the event concluded, although one of them was carried by a single title jumping immediately into another event. 6

The point of this section is simple: there’s very little predictability to all of this. While that first chart looks nice and neat – Mission Accomplished! Events are good for related titles! – things are rarely quite that simple. So let’s drill down a little bit to look at some curious things I discovered in the process.

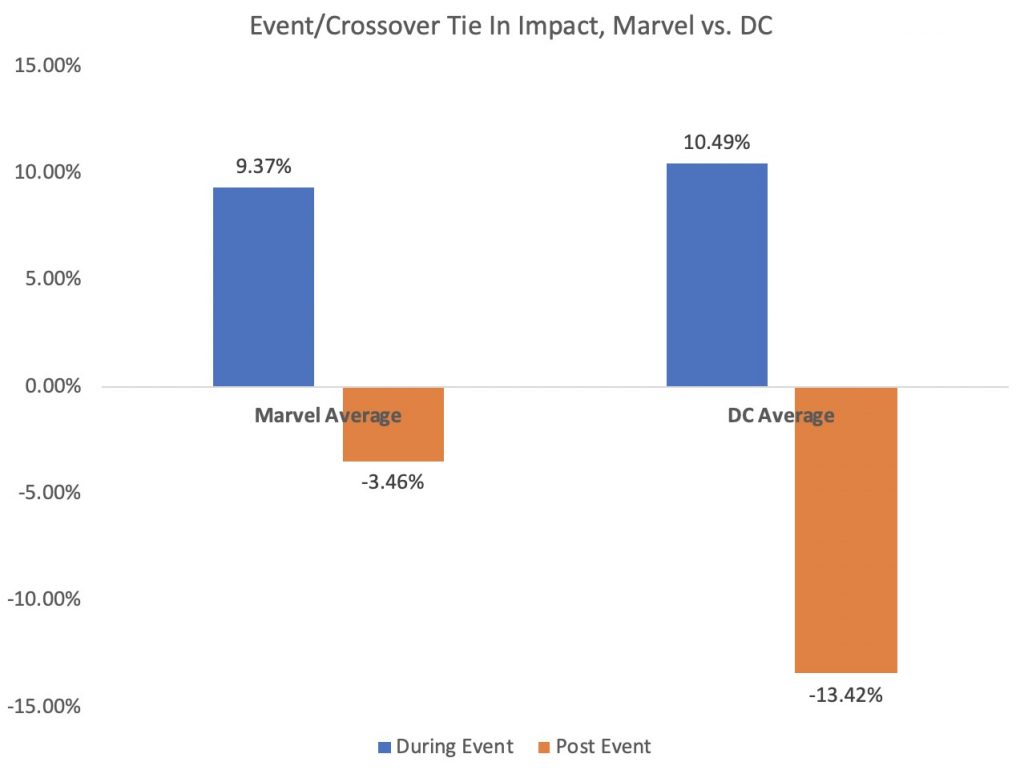

The first trend is related to a predictable idea given the two entities we’re primarily talking about. I’m of course talking about Marvel vs. DC. What’s odd is how much broader the spectrum of results is for DC event tie-ins versus its opponent at the top of the direct market. Here’s a chart showing just that.

Marvel’s total range is separated by 12.83%, suggesting a little more predictability for them. Generally speaking, if a specific Marvel title is tethered to an event, it should help a fair amount without harming it afterwards. That’s good!

It is also not the case for DC.

Its range is 23.91%, which basically means the risk reward for DC tie-ins is incredibly broad. It may dramatically increase sales during the event! But it also may kill the books afterwards! Part of that stems from the fact that DC’s events themselves are incredibly unpredictable. While something like Blackest Night or even Metal are widely liked, Forever Evil is something you could describe as “at best forgettable” and Final Crisis was polarizing, to say the least. Because of that variance in the events themselves – and the honestly wild mix of titles that get lumped into these stories – it shouldn’t be too surprising that tie-ins at DC are erratic performers.

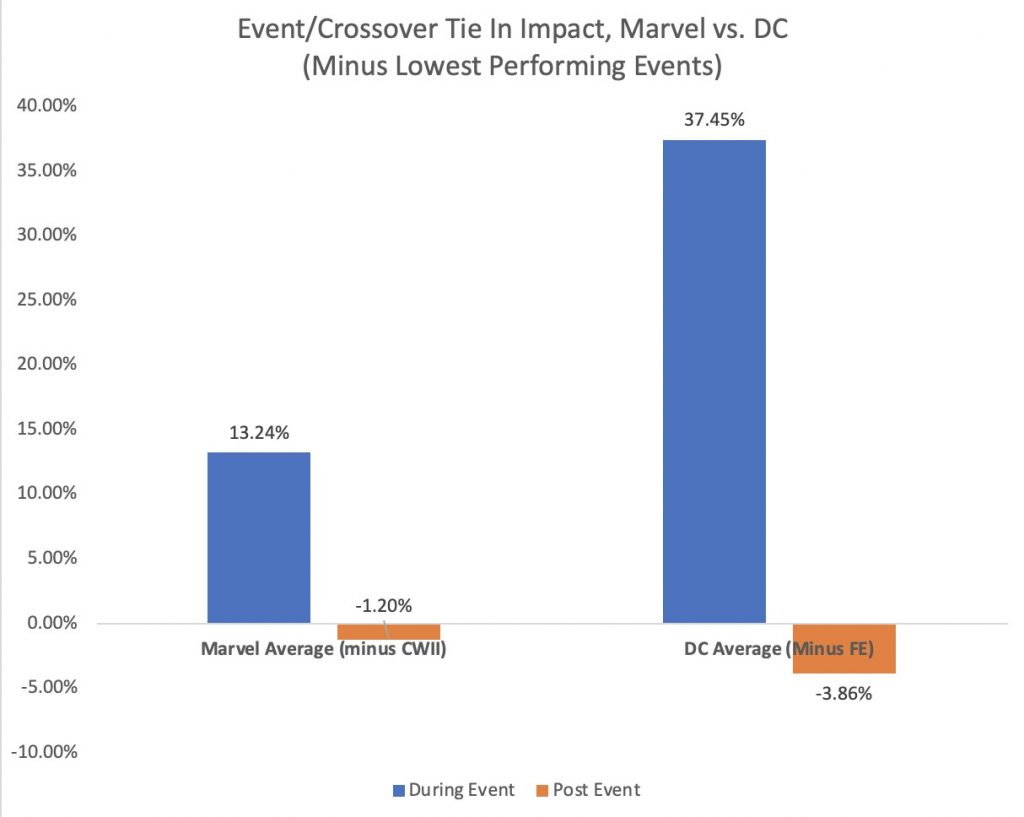

I mentioned earlier, though, that two events were outliers relative to their peers, both in gains – or the lack thereof – during the event and drop offs afterwards. Those were Civil War II at Marvel and Forever Evil at DC. I was curious what this chart would look like if you removed those two from the equation. So I sliced the data that way for another chart.

Well that is different, at least on the DC side! If you ignore Civil War II, it shows Marvel titles have decent upside and very little downside when it comes to being roped into events, which isn’t all that different then it was before. But if you remove the anchor that was Forever Evil, you see DC’s ceiling – thanks to the outrageous performance of Blackest Night and Metal‘s tie-ins – is immense and the cost isn’t that bad at all on average.

Here’s where my sneak attack point comes in, and this trend shouldn’t be that unexpected. Tying into an event is largely a good thing for a title – higher upside, minimal downside – if that larger story it’s connected to is generating excitement itself. Civil War II and Forever Evil were relative duds from event history, and they generated meager performances amongst tie-ins. Expanding this further, two of the other weakest performing sets of tie-ins – both in lift during the event and in mitigating downturn after it – were, perhaps predictably, related to Secret Empire and Final Crisis. Meanwhile, the best performers were tied to the most well-liked crossovers, at least on average.

So what does that mean? If an event is generating excitement or is considered good and worthwhile, it typically results in wins. If it isn’t, prepare for that L. Perceived quality of the larger story can seemingly impact tie-in titles dramatically.

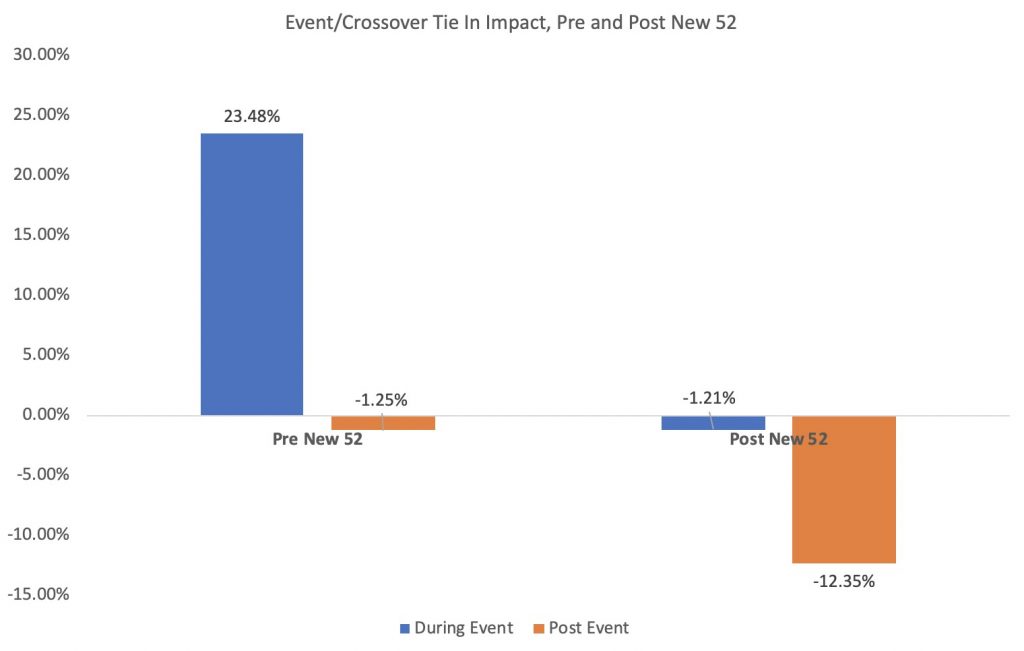

This is my favorite thing I discovered, even if it isn’t actually a good thing. One key element in terms of the performance of tie-ins is time. You might be wondering what I mean by that. There’s a genuine dividing line at a specific point in recent comics history where event tie-in performance took a nose dive. Basically, if you look before The New 52, tie-ins worked rather well. Since then…not so much.

How wild is that? Before The New 52, events and crossovers generated significant lift for related comics on average, with those same titles facing very mild downturn after the event concluded. Of the five events I looked at from that period, four saw double digit percentage increases, ranging from 58.08% to 17.12%. Of that same five, only one saw a greater than three percent decrease post event. It’s honestly incredible.

Since The New 52, event tie-ins have on average been ordered at lower numbers than the issues preceding them. After the event is over, the downturn is even more dramatic, with titles typically seeing a 12.35% decrease. While that’s heavily impacted by both Civil War II and Forever Evil coming within that period, as they were anchors designed as saviors, only two of the five events from this period generated an increase in sales for related titles during the story – Metal and, of all stories, Secret Empire – and three of them saw post event downturns of greater than eight percent.

This is another one of those definitive moments where it seems like we’ve learned something. “The New 52 killed event tie-ins!” you might be thinking. And you may be partially correct. Based off the data – especially when combined with finding out just how many tie-in titles just end after these more recent events, as it’s 50% of the titles I looked at on the Marvel side concluded afterwards and 20% for DC – it seems that shops are now ordering event tie-ins expecting drop off amongst readers. There are exceptions, of course, as Metal was a bonanza for connected titles, and this is by no means a universal idea, as specific titles weigh down the averages. 7 But when even an A-list comic like The New 52’s Justice League sees a downturn in orders when it connects to an event like Forever Evil, you know it’s a problem to a degree.

I wonder what it comes from? Could it be that all of the relaunches and reboots at Marvel and DC convinced readers that if they’re not feeling something, they can bail because a new volume will almost certainly be right around the corner? Could it be that tie-ins just aren’t as fitting or obvious as before? Could it just be that events within this era are just worse than the one before it?

That last point has legs, to a degree. As I mentioned earlier, there seems to be a qualitative correlation, where a good event leads to gains and a bad one leads to diminishing orders. And I could make a very strong case that four of the five events I looked from this period were at best polarizing, while those from the preceding period were at a minimum decent superhero comics. I think it’s a bit of column A and a bit of column B. Events aren’t quite what they were before, but also, readers have been retrained and shops have adjusted accordingly.

But I would also argue that this trend isn’t necessarily about post New 52 events being universally ordered at lower levels as much as it is about how the series of relaunches over the past decade have created an atmosphere of unpredictability for retailers. So instead of ordering expecting a rising tide, shops manage risk by dialing tie-in orders back, hoping to make any shortfall up with reorders. When an event has genuine heat behind it, like Metal, they order expecting an area of effect on surrounding titles. Anything less than that? They seemingly decide to play it safe. It’s hard to blame them.

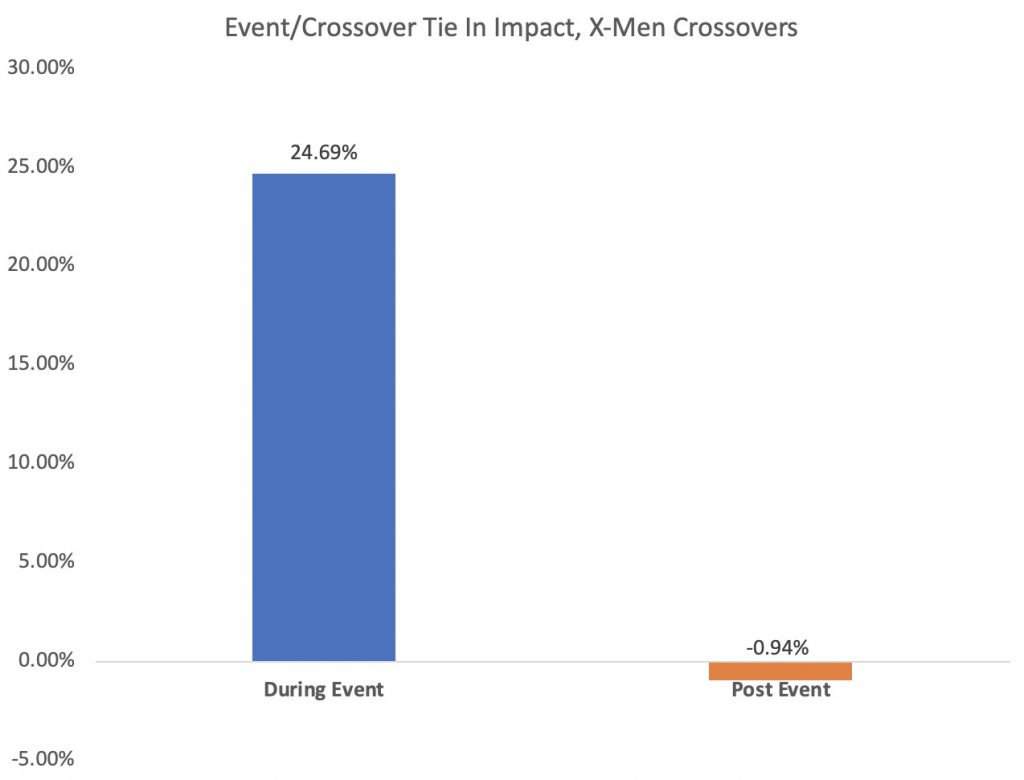

Given that this all started with an X-Men crossover generating the question I’m attempting to answer, I wanted to look at the two most recent, most similarly structured X-Men stories to help me envision how X of Swords might shake out from an ordering standpoint. So let’s look at one final chart, with this one looking at how the combined performance of the titles that comprised X-Men: Messiah Complex and X-Men: Second Coming shook out.

This structure seems to work! Related X-Men titles – namely, Uncanny X-Men and X-Men/X-Men Legacy, in particular – saw consistent, significant gains when fused together in an X of Swords-like structure. Granted, those stories were legitimately half as long as the upcoming crossover, but still! That’s worth noting. Beyond that, there was minimal impact to the long-term fate of related titles, with five of the six titles I looked at 8 even seeing higher orders on the first issue out of the crossover than the two that preceded it. It seems as if these stories genuinely led to individual titles discovering other X-Titles and shops adjusting orders accordingly. To label it in a way that is far too on the nose: it’s uncanny.

Now it’s worth noting that it’s been a long time since either of those events – Second Coming is a decade old now! – and that they behave differently than standard events, because the tie-ins are the event here. But these interlaced crossovers in the X-Men line seem to result in real wins for participating titles, both with readers and retailers.

In X of Swords, though, the strength of this flavor of X-Men crossover is coming into direct conflict with other trends we’ve examined here to a degree. It will be interesting to see how it plays out, because X of Swords is simultaneously a test case to all three trends I’ve looked at here: the quality of the story being important; that events haven’t led to significant gains in recent years; and that X-Men crossovers generally lead to wins for everyone.

Again, X of Swords is by far the longest X-Men crossover yet, and it’s being released during a pandemic and economic crisis. Many of the individual issues are also very expensive. That’s a tough ordering environment. It’s a noisy as heck situation, and one where an unexpectedly poor performance could be easy to explain. But on the surface, this mega-story seems as if it could be a bellwether for the potency of events and crossovers, if only because of how well it operates within the confines of the ideas I’ve laid out here. How will it play out? We’ll find out in about a year, but I think it will do fine once you factor in that Hickman Heat.

All that said, as much as each of these trends are worth mentioning, I do want to note this: while I don’t think I was completely wrong with my jumping off point theory for event tie-ins, having looked at it, I do think these kinds of crossovers are worth the risk for publishers. Even now, they can have a considerable impact, if the project they’re connected to is worthwhile. 9 They seem like they can lead to increased interest on the retailer level – if consumers are behind it, of course – and if the stories work well, attrition can slow and titles can see post event gains. Pair that with the high ceiling of the potential impact during the event, and I’m going to say tying in to events is a net positive overall for individual comics, even if they don’t always feel like it.

Well, more specifically, it’s 22 chapters long with two prelude issues.↩

Like Layla Miller, I like to know things.↩

You might be wondering: where is Secret Wars? Well, that had tie-in titles, but those titles replaced all of the existing books, making it impossible to have apples to apples comparisons.↩

The reason there is if I exclusively looked at A-list titles, these numbers would be far more resilient, showing less drop off. If I only looked at lower tier ones, it’d be more severe. Balance was necessary.↩

Forever Evil is going to get picked on a lot here, but I should note, it had a very small amount of tie-ins, and two of them ended quickly after the event did. It’s a bit of an oddball from history.↩

That was, again, Venom going from tying into War of the Realms to its connection with Absolute Carnage.↩

Lower tier titles, which used to see tying in to events as a life raft, are sometimes dramatically harmed by them now.↩

One tie-in from each of these two stories were almost immediately relaunched after the crossover concluded, thus why it’s only eight.↩

Here’s something to consider: maybe have fewer events, Marvel and DC! It would likely result in higher quality and a greater impact to these tie-ins. Just a thought.↩